As Penrose’s statement makes clear, her poses reflect her physical and mental state – but these poses are not consciously formed. Each time she makes a portrait she goes to a different space and just reacts, finding the best position for the space and opting to shoot with a timer that gives her just seconds to move. “I just turn up at these places with no idea – most of the time I’ve never been there before, so I don’t know what to expect,” she says.

“I get into the space and I think, ‘OK, that table looks interesting, I can get into this pose and be confident I can do it 60 times.’ Then I set up the camera and take it with clothes on, have a look and think, ‘Yes, that looks worth working on.’ Then I’ll put the self-timer on and turn into a visual version of a broken record, just going and going, and every time I look at the back of the camera, I’ll think: ‘Right, that doesn’t work, I need to arch my back more, I need to point my toe, I need to really get my hip further to the side of the chair and so on.’

“By the time I’ve done that 50 or 60 times, my body remembers it and those are always the ones that make it into the edit, never the first ones – it’s by that rhythm and my body remembering it and perfecting it. Then I wake up the next morning and I can’t move.”

It’s often only in retrospect that she realises what the images say about her feelings; looking through the series as a whole she has realised it records seismic shifts in her thinking, as well as her day-to-day emotions. When she started she simply wanted to show an active, capable version of a female nude, she says, but after having a baby her relationship with her body changed. In the earlier images she tends not to show her breasts or pubic hair, for example; after giving birth, she frankly depicts her entire frame.

“I think there’s something about having a baby that makes you respect your body and realise how brilliant it is – how clever it is and what it’s done,” she says. “That and the fact that throughout pregnancy and in childbirth you have to show every crevice of your body to other people means you become much less body-conscious. Your view of your body completely changes and your self-consciousness just disappears – or mine did anyway. I feel more frank about it; it’s less of a sexual object and much more of a machine for keeping another being alive.”

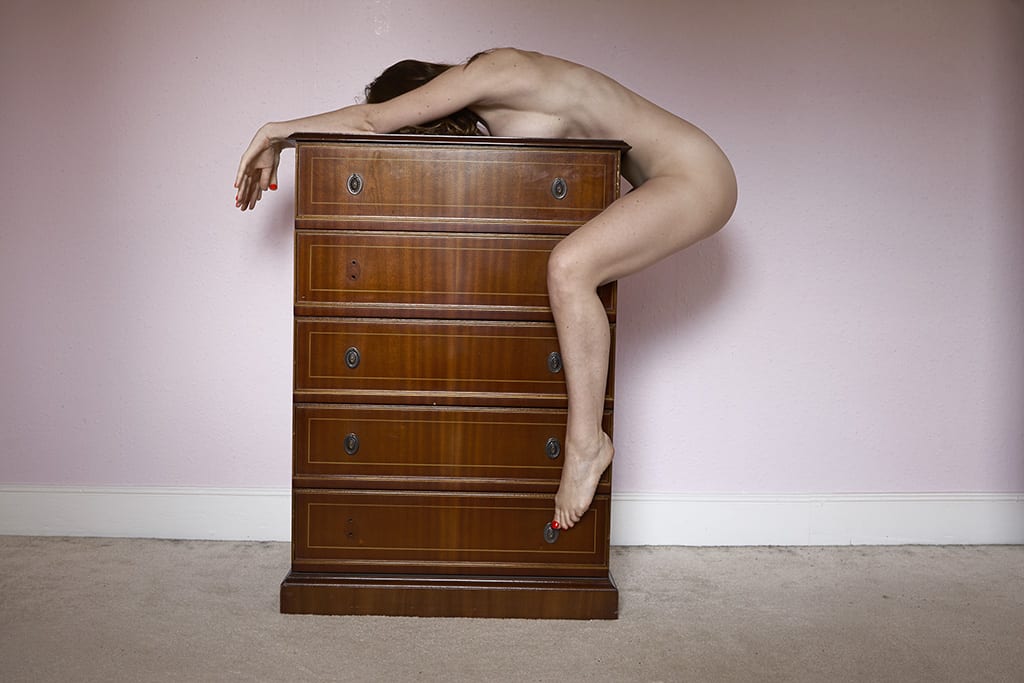

Penrose also shows some of the stresses and strains of her newfound situation – a picture taken on a cramped space on top of a chest of drawers speaks of the constrictions of new motherhood, for example, while a later shot, taken when she was pregnant again, shows her bowing her head against the wall in mock resignation. “It’s really humorous, and I think some of the earlier ones are also playful,” she says. “That gets lost somewhere around having George [her first child].”