In 2015, the cross-pollination of races occurs freely and globally. Yet it is easy to overlook the complex process of identification that a mixed-race person must confront. For in each race’s DNA is a history, culture and psychology that are all too-often defined in isolation.

In his most recent series, Frantz Fanon, which tracks the life of the iconic 20th century thinker, Bruno Boudjelal has continued his career tradition of using photography to untangle the rich web of his own mixed identity.

Frantz Fanon is widely regarded as the definitive post-colonial theorist. Born in Martinique, he traveled to France to fight in the Second World War before settling in North Africa, working as a psychiatrist in a small town, Blida, 50 miles from the Algerian capital. It was here, in the years leading up to both its release and Fanon’s death in 1961, that he wrote his chilling account of the psychological effects of colonialism and decolonization on the native Algerian population, Les Damnés de la Terre – ‘The Wretched of the Earth.’

“For anyone who is interested in race and the psychology of race, at some point, you come to Fanon. You have to. We commissioned Bruno to go and look for him,” Mark Sealy MBE, curator and long-time friend of Boudjelal, told me when we met at Autograph ABP in Shoreditch, London, where the series is on display. The institution, of which Sealy is Director, is familiar with showcasing the photography of race, culture and identity politics.

“This work is one of symbolism. It is about trying to find yourself through the physicality of Fanon’s journey,” he explained. “How can you ask about Fanon without necessarily talking about his journey as a Martiniquan arriving in Europe to fight the Germans? That was when he realised his own negritude – this is similar, I think, to what Bruno has experienced.”

The photography in this series was born out of Boudjelal’s travels in Algeria as well as Martinique, Ghana and Tunisia. Set around a low-lit, introspective room displaying the photographs alongside piercing extracts of Fanon’s writing, the series is both a biographical show of historical documentation as well as an honest, frustrated exploration of the mixed-race self.

Like so many of his generation, Boudjelal only came to discover his half-Algerian ethnicity in adulthood, long after his father had originally cut ties to Algeria, having emigrated to France in the 1950s. Setting out as a novice photographer, armed with strictly black-and-white film, he first traveled to the country in 1993 in search for his family, and was confronted with the impenetrable, bloody chaos of civil war. But in the years since, especially post-2003, with Algeria returned to relative peace, his volatile relationship with his fatherland has evolved into a source of deep personal confusion and artistic expression.

“The question soon came: do I belong in Algeria? It was very disturbing for me,” he told me over Skype last week. “In 2009 I decided to start a project to explore this feeling, and I went with Fanon.”

Boudjelal explained to me the difficulty of finding and documenting Fanon’s life in Algeria, whilst trying to find his own harmony with the country.

“The series is about learning to work with the process of failure. Never have I gone to Algeria and found what I expected,” he explained.

Having first come across Fanon on a trip to Martinique with his wife (who herself is from the former French colony), Boudjelal made many unsuccessful attempts to visit various Fanon landmarks: his house, the hospital in Blida and a mausoleum near the Tunisian border.

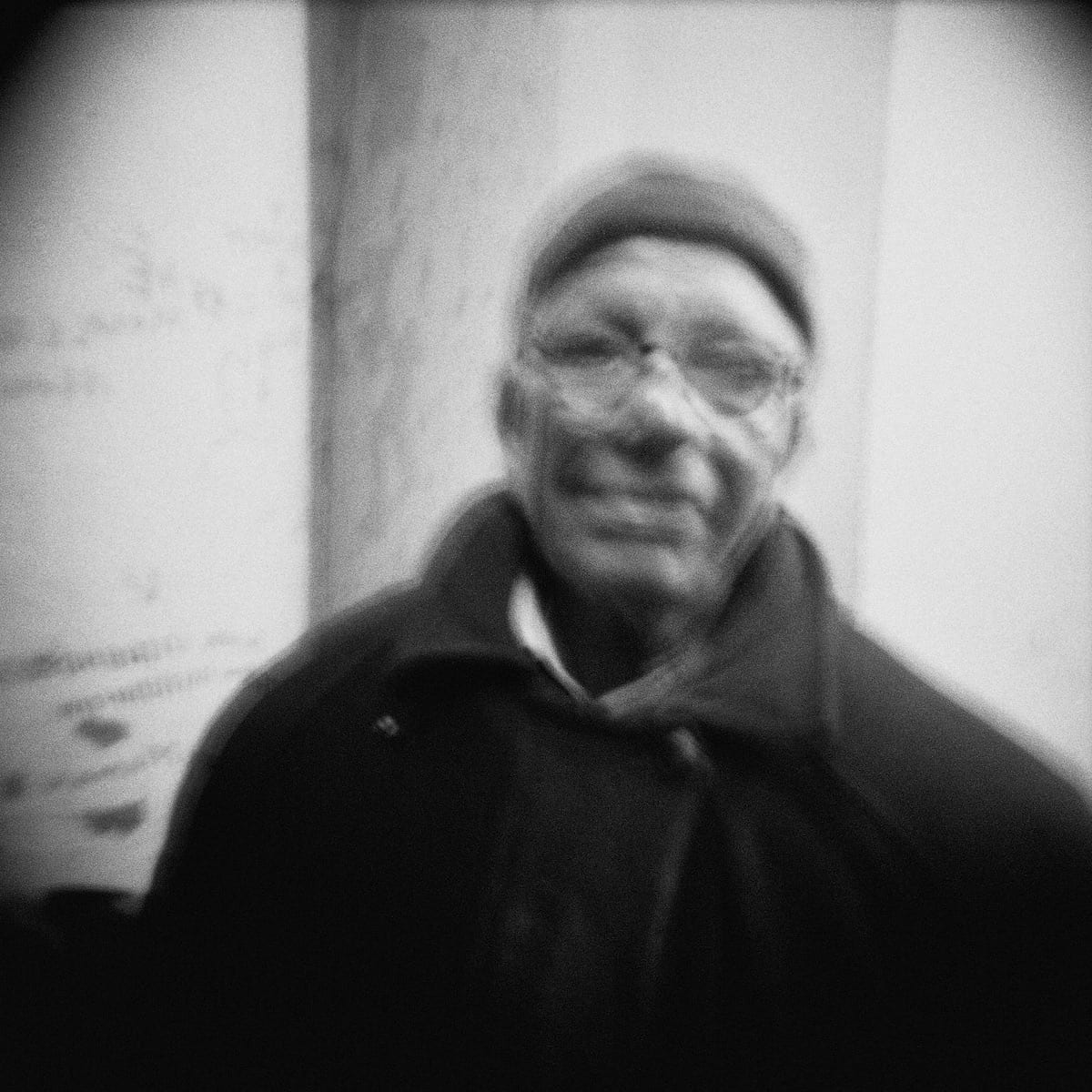

On his visit to the hospital, for example, (after two failed attempts), Boudjelal found and photographed Fanon’s single remaining patient, who has lived on the premises as a groundskeeper for over fifty years. The portrait features in the series as one of several equally chilling photographs taken at the hospital.

“The guy is like a memorial, because he saw everything,” Boudjelal told me. “But still, he would not talk to me. I took three photographs of him and then he was gone.”

This particular encounter is reflective of what Boudjelal found to be a constant feeling of inaccessibility towards Algeria; the realisation that no matter what steps he took to dig deeper into Fanon’s legacy, and his own feeling of confusion, he kept coming up short.

“I have tried to find Fanon, and understand Algeria,” he said, “but I do not have access to them. For me, this is important – it has meaning. It tells us about legitimacy – am I allowed to be there?”

Once we had finished discussing his photography, Boudjelal closed the conversation with an anecdote.

“I have dual nationality: a French passport and an Algerian passport. During the civil war, I went to Algeria with my French passport and a border policeman said to me: “Why do you not have an Algerian passport? You don’t like Algeria – are you ashamed?

“So on the next journey, I traveled with the Algerian passport. And when I arrived, now the guy says: “You are Algerian? We give an Algerian passport to a person like you? Ah, that is a pity.”

“So,” he finished, “what can you do?”

‘Franz Fanon’ is showing at Autograph ABP, Rivington Place until 5th December 2015. Entry is free to the public.