As photography began to spread amongst Europe’s artistic communities of the 19th century, so a debate raged, one that, in many respects, is still alive today.

Can photography be capable of more fully and accurately depicting life than painting?

Photography is a mechanical representation of reality. But, for many artists at the time, it was also inherently inferior.

In response, throughout the 1920s, the Pictorialist movement emerged, in which photography followed the rules of painting to lend it greater artistic authority.

It’s this tension the new exhibition in Zurich explores, its central themes exploring the Neues Sehen, or ‘New Vision’ in Germany, as opposed to the Surrealism moment in Paris, and the avant-garde movement that came out of Prague.

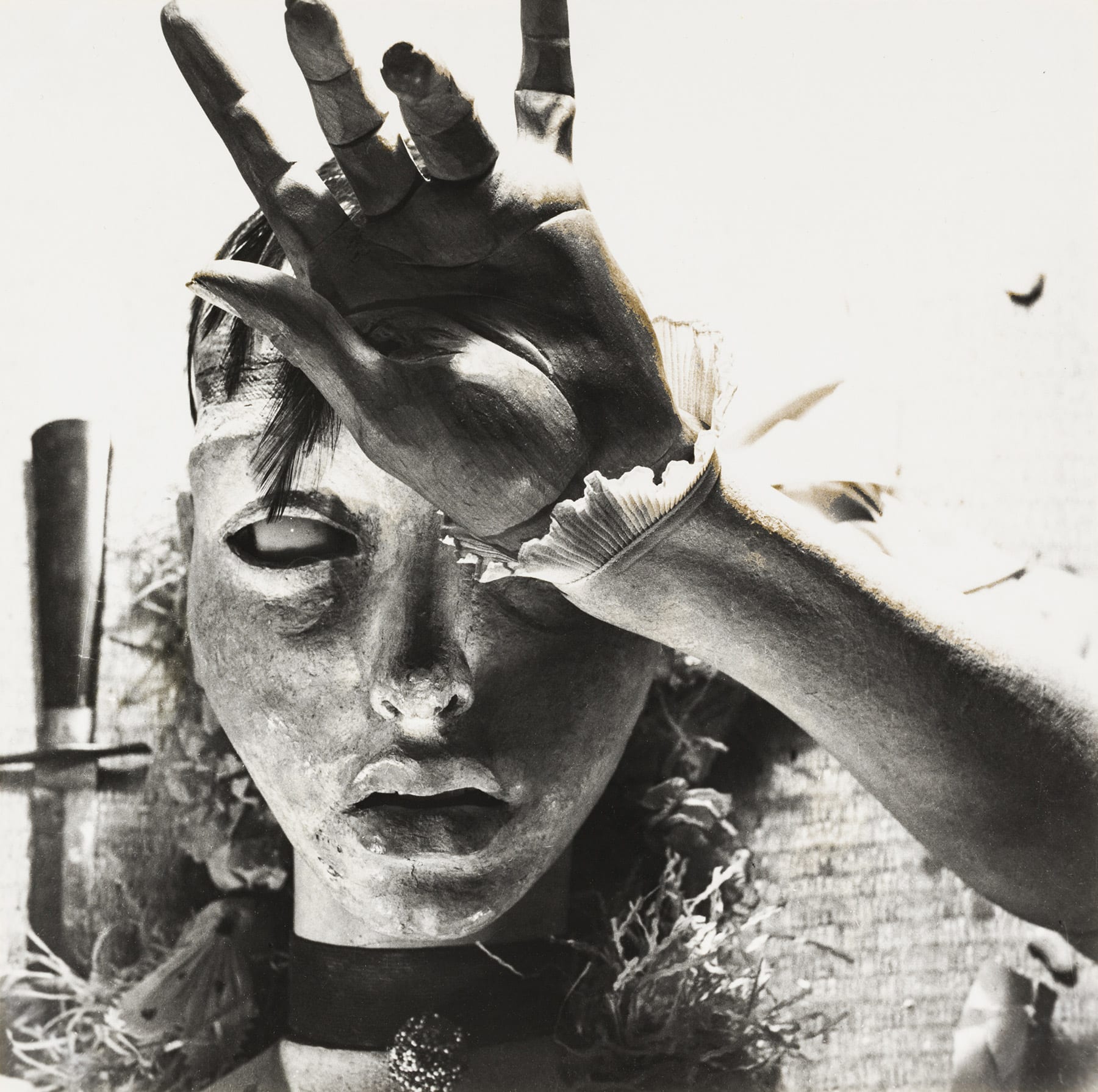

The show encompasses some 220 photographs, a selection of historical photography books and magazines as well as rare artists’ books, showing portraits, nudes, objects, architecture, and photographic experiments which “play with the divides between the real and the surreal.”

Several famous examples of surrealist filmmaking, including An Andalusian Dog by Louis Buñuel or Berlin Still Life by László Moholy-Nagy, illustrate the exchange between avant-garde photography and cinema throughout the era.

The photographers of the Neue Sehen sought to show the world as it was. They saw photography as the “reliable tool”, something that could objectively depict the visible things of the world, and was thus superior to the vagaries of the human eye.

This very austere take on society turned buildings and streets into compositions of lines and surfaces. But, viewed another way, such photography could create an unexpected dynamic, significantly enlarging an object, for example, or decontextualising it to the extent of alienation.

The Surrealists, therefore, recognised the artistic potential of écriture automatique, or so-called “thought photography,” in the supposedly realistic recording of the camera. Beneath the surface of the visible world, they sought to explore the irrational, the mystic and contradictory.

Ironically, so-called documentary photographers became an inspiration for the Surrealist movement. Montage became one of the most important artistic tools of Surrealism, creating images out of combinations of pictures, with new, surprising visual contexts.

The show displays Karel Teige’s collages, Brassaï’s pictures of Paris at night, and Man Ray’s photograms, which capture dream-like impressions of light.

Staged photographs, as well as the many technical experiments with multiple exposures, negative prints, and polarisation, sought to fuse dreams and reality, as André Breton stated in his first manifesto of Surrealism.

“I believe in the future resolution of these two states, dream and reality,” Breton wrote, “which are seemingly so contradictory, into a kind of absolute reality, a surreality, if one may so speak.”

For more information on the exhibition at Museum Bellerive, see here.