But unlike many who binge on travelling after university, Klein did not subsequently settle down to a career somewhere in the vicinity of his degree – an MA in public health and epidemiology.

Instead, he developed a life-changing passion for photography that would propel him on yet more adventures.

Since then, his travels have delivered several distinctive collections; covering grassroots musicians in Haiti and Jamaica for Against All Odds and Alpha Boys respectively, whilst honing his style in more straightforward travel photography with Salvador, Bahia (Brazil) and Calais (France).

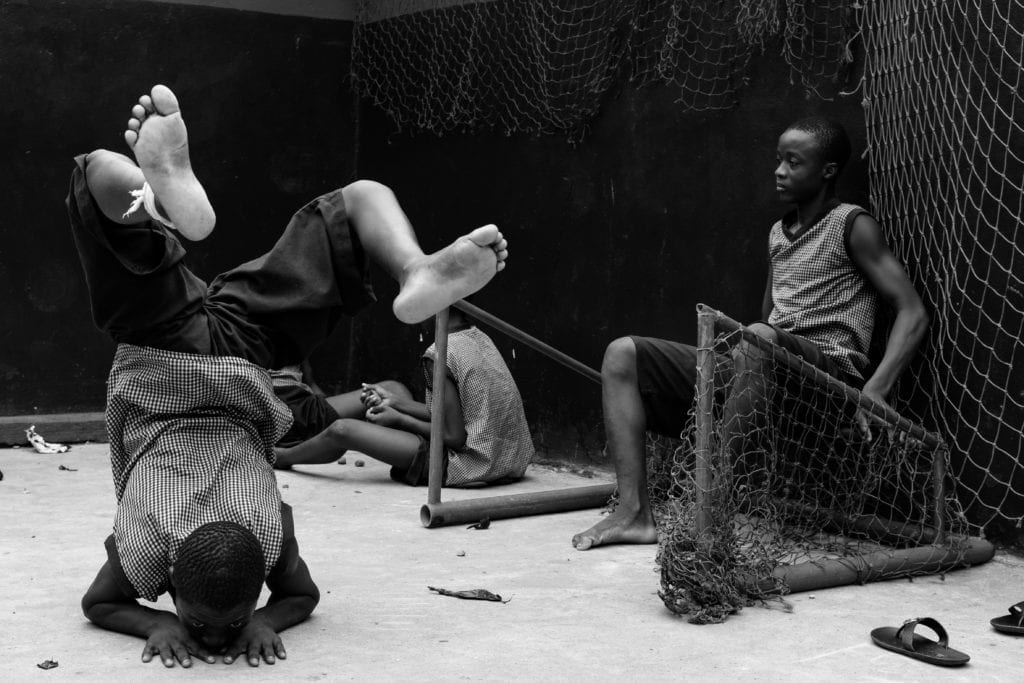

However, after spending time on a follow-up project, Klein looked elsewhere. ‘I wanted to show a different picture of Africa’, the mohawked photographer suggests over coffee in Central London, ‘not so stereotypical. Usually you just see starving people or you see warzones or other horrible things, but you don’t really see the daily life and the happiness that poor people have.’

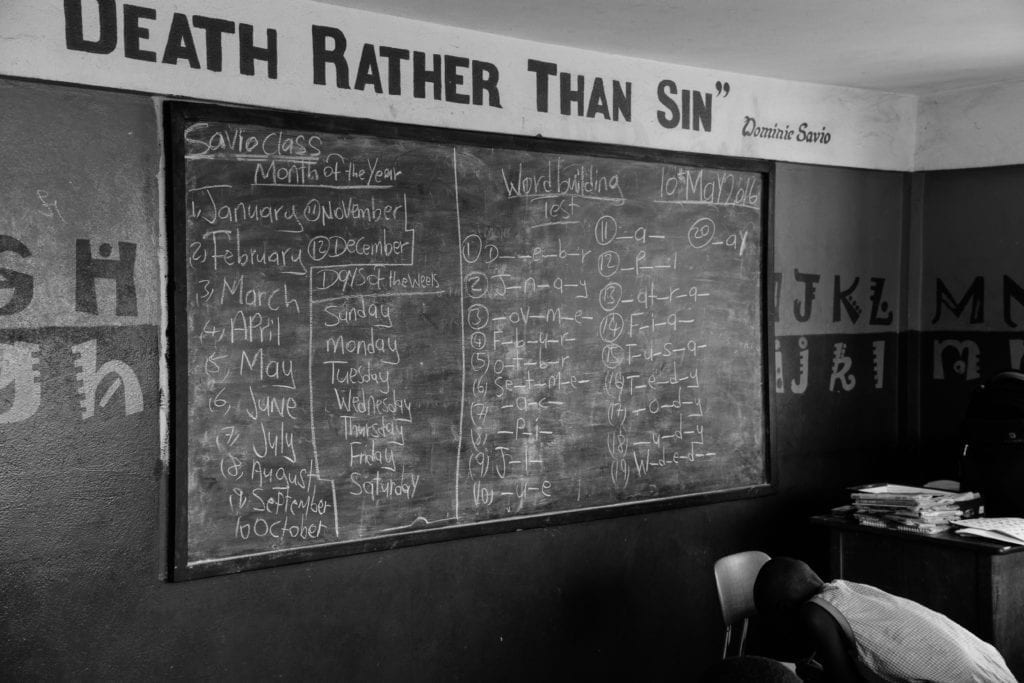

Many of the most revealing shots are taken from five weeks spent in the Don Bosco Mission in the heart of Freetown – a Roman Catholic institution that offers 11-month educational programs to orphans, delinquents and other youngsters who have fallen out of the system. These homes were initially founded in the mid-to-late nineteenth century in Italy, France and Argentina, quickly spreading to Africa, Asia and beyond. It remains, by some counts, the third largest missionary organisation in the world, operating over 2,500 houses.

‘Usually when I go somewhere, I just carry a camera around, and I don’t have a plan, and if I see something that makes me stop, I start shooting as many pictures as I can in a short time. I visit the same places over and over again [until] they don’t really care about me any more because they have seen me so many times.

‘They see me as invisible and they don’t look at the camera any more. That is the goal.’

Indeed, any Westerner who has visited the global south can probably appreciate the curious huddle that often occurs when a stranger enters town – especially one armed with a camera.

‘I don’t know if it’s changing anything but maybe people are [becoming] aware of what’s going on – maybe seeing a different picture of Africa. They have nothing, but they have much more than some Western people who have lots of material things.’

For more information about the photographer, visit here.