In one of the accompanying essays for Daniel Stier’s book, Ways of Knowing, Pedro G Ferreira, a professor of astrophysics at Oxford University, describes the scientific process in a surprising way.

“I found experimental work to be a different way of doing, unlike art or theory, yet, in some ways, much more organic, irrational and intuitive.”

We are accustomed to making firm, simplistic divisions between the creative freewheeling art world and the disciplined, empirical structures of science.

And yet here is an Oxford Don extolling virtues not commonly associated with the science of our imagination – organic, irrational, intuitive.

It’s precisely this apparent contradiction that so attracted Stier, whose book consists of two projects that explore his fascination with the experiment as an artform.

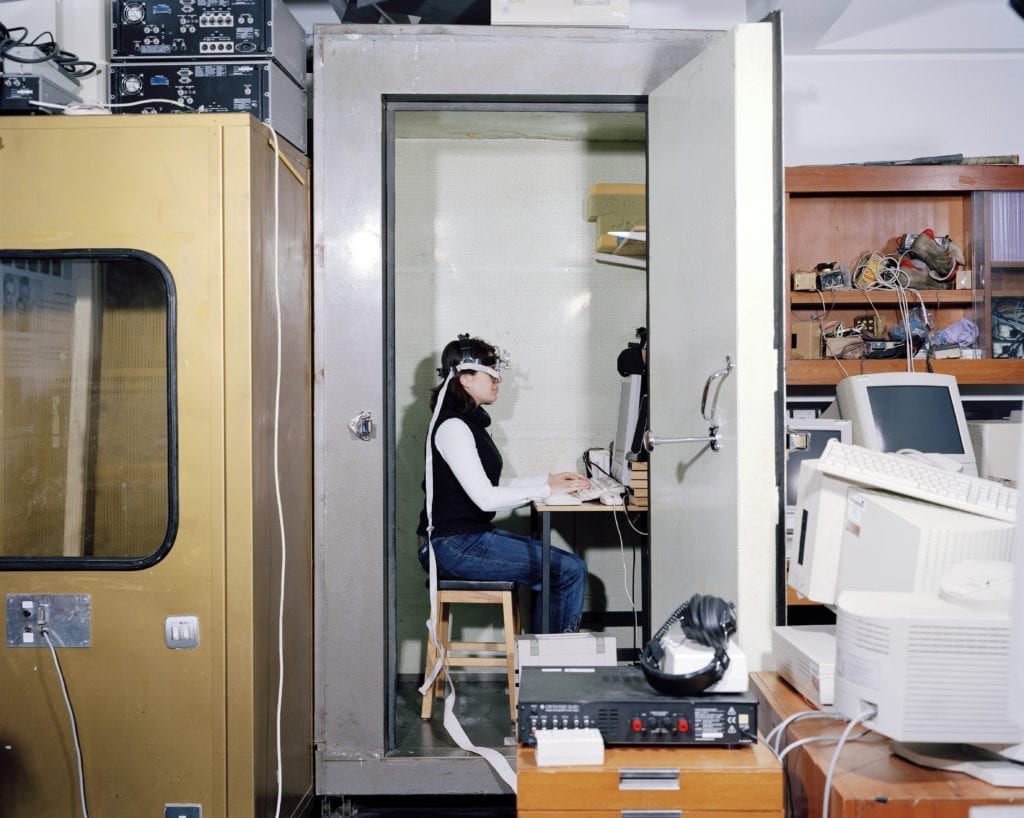

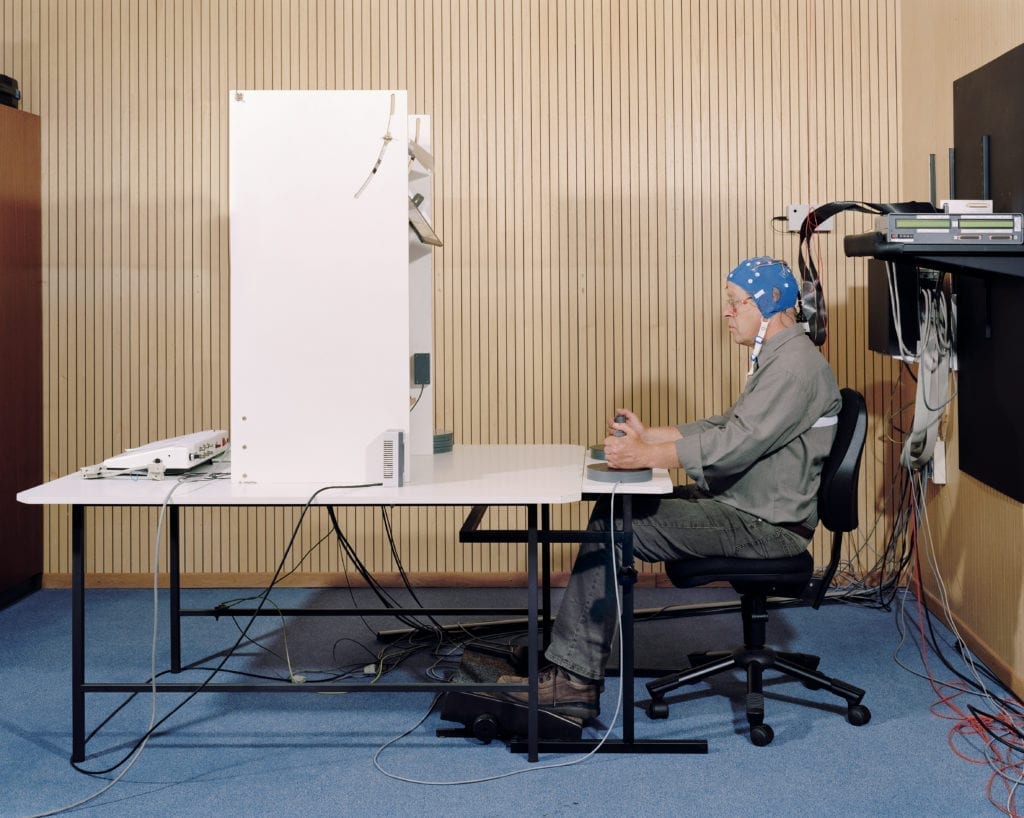

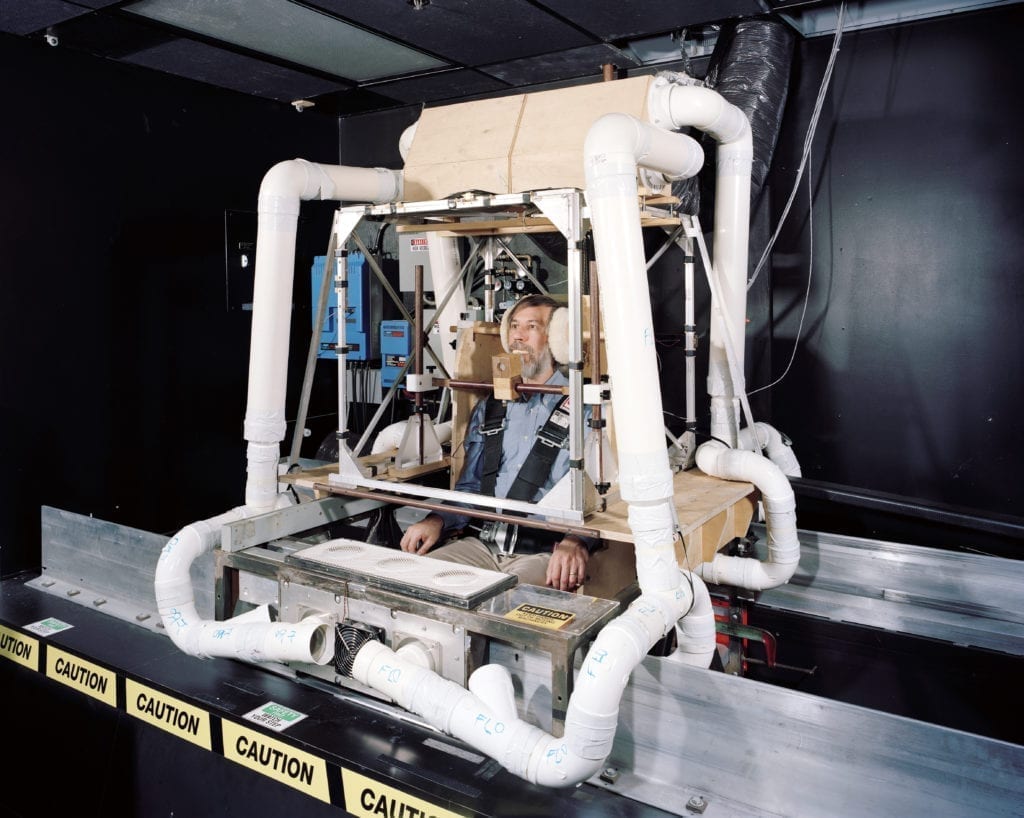

It was around 2008 when the London-based photographer happened across an image of an experiment involving a human subject, and became fascinated by the interplay between the strange environment and the unknown exploration he was looking at.

He began making enquiries, sending dozens of emails and relying on introductions from friendly subjects to others who could help him get into the institutions where these weird and wonderful experiments were taking place.

The only rules were that they should each include a person – a student, researcher or professor involved in the project – and that Stier would document what he found, rather than setting up or directing scenes.

Shot across Europe and the US – from Munich to Sheffield, Zurich to Philadelphia – the 32 photographs showcased in Volume 1 of Ways of Knowing build up a baffling picture of contemporary science.

“There’s a wrong idea about scientific research – that National Geographic look, all white lab coats and stainless steel surfaces,” Stier laughs.

“When you shoot science, you are almost obliged to use some violet light, because that’s what we think it looks like. The reality couldn’t be more different – as you see in the pictures, it’s hand-made, retro, a lot of string and tape. There’s a lot of basements.”

He was beguiled by this lack of glamour, although there is more diversity across the series than he suggests. One or two of the images really do look futuristic, with gleaming contraptions straight out of central casting (Stier says this was usually in Germany or Switzerland where funding was better).

But they are the exceptions rather than the rule – the majority of the set-ups he presents are gloriously, almost laughably, lo-fi, with contraptions made of scaffolding poles that seem half gym machine, half cut-price sex dungeon.

“Scientists couldn’t care less what the lab looks like, it just needs to function,” Stier says. “That’s the beauty of it as well, nobody even thinks about making it look pretty.

When it came to printing the images though, Stier found the artificial environments made his job much tougher. Because there were no natural colours to reference – a blue sky for example – it was difficult to make sure the colours were coming out correctly.

Further complications arose when his initial publishing deal floundered, and in 2010 the German photographer put the photos away to concentrate on his busy commercial schedule.

But he kept coming back to the themes and eventually he decided to shoot a new series. The 39 photographs that make up Volume 2 of Ways of Knowing are a mixture of moments captured in his studio that toy with the visual language and the mixture of “circus act, art and science” that he remembers from those first experiments we encounter at school.

While most are bogus creations of his own mind, others are recreations of illustrations from the popular 19th Century French magazine, La Science Amusante.

These experiments were designed so that readers could do them at home, and so they involve mundane objects like umbrellas, wine bottles and a baguette bag.

For Stier, this new series allowed him to fundamentally explore the photographic process. “It goes back to that evidential idea of photography where we are documenting something, but there’s a before and there’s an after, and somewhere along the line there’s an image that grabs that one moment,” he says.

He admits to a few nerves as he went to meet Ferreira for the first time in Oxford, armed with his new series. “I wondered what this eminent professor was going to think of this frivolous child’s play,” he says. “But he could relate to it, and he said, ‘This is what we do’.” As Ferreira talked about the creative ways of approaching a problem, and how he was driven to find elegant and beautiful solutions, he articulated what Stier had discovered, that art and science weren’t so different after all.

“I find it magic,” Stier explains, “the idea of doing experiments to get somewhere with the in-built possibility of failure. I am interested in the experiment, the idea of work that people do without any clear outcome. This constant loop of doing something, maybe failing and then starting again. That is exactly what we do as artists.”

Drawing these parallels is not a completely new idea, but the more Stier thought about them, the more he became enchanted by the crossovers, and the sheer courage of the creative act. “It is very simple; you just have to do it. It’s still a strange feeling as an artist – you go into your studio in the morning and there’s nothing there, and you come out in the evening and there’s something.

“I try to keep it very minimal, use very simple materials, and there’s the other parallel because a laboratory is exactly the same. It’s an empty room into which you take the materials you deem interesting for the work. You separate yourself from the real world.”

The two volumes are printed tête-bêche style, so that you can start from either cover, and there is an impasse in the centre where the two sections finish. This was to underline that these are separate projects that explore the same subject matter, rather than one single creative entity.

The second series has no captions at all, just a mind-bending essay by the artist Daniel Jewesbury – part poem, part philosophical treatise. For the photographs taken in the institutions, there is an index which lists the locations but gives no more explanatory detail. It’s up to the viewer to guess what is going on, and Stier likes this uncertainty.

“The interest wasn’t to do scientific reportage,” he says. “There’s a tendency with editorial to over explain stuff all the time. Journalists freak out when there aren’t any captions, but the impact as an image-maker is much greater.

“I don’t like artists that tell me how to see the world. I like more the people who ask intelligent questions and leave me open in how I respond to them.”

Ways of Knowing is published by Yes Editions, priced £35.

ways-of-knowing.com

danielstier.com