It sounds like an attitude he can afford, at this late stage in his career, but for Bailey it’s ever been thus. He stopped giving Vogue his contact sheets 40 years ago, when he realised “the only ones they liked were of someone laughing”, he says; he’s got choice words for editors who get too involved.

“I never understand why someone will ask you to do something and then turn round and try to tell you how to do it,” he says. “Why don’t you do it yourself then? An art director. I can take pictures better than most of them, so why would I listen to an art director? Or an editor for that matter. Why tell me what to do? I was fighting all the magazines for years, because they’re run by people who are not visually literate.”

Similarly, he says he’s “not very good at commercial jobs”, because he hates being told what to do. His fellow 1960s trail-blazer Brian Duffy used to call him “the amateur” because of it, he laughs: “He’d say, ‘They ask you to do a job and you nod, and smile, and say yes, and then go and do what you like.’

“But I don’t want to do it, I don’t want to be a professional photographer. I don’t like the idea of being a professional photographer – just be yourself.”

If he does do a commission, he shoots what he wants, and he works with creative people not “advertising agencies, that are basically making money”. When he’s shooting for Valentino, he speaks to Pierpaolo Piccioli, the creative director of the brand; when he shot commercials, he was working with Jay Chiat, “a maverick in corporate America”.

“Since he died I’ve never bothered to make a commercial, because I can’t deal with the corporate brain,” he says. “I’m not interested in somebody that’s not creative. Why would I be?

Similarly he says he doesn’t shoot celebrities, describing the many A-listers he’s worked with as “talented”, and pointing out the many others he’s also shot over the years. “I shoot such diverse people, from headhunters to politicians, it’s whether I find the person interesting,” he says. “I’m interested in people who have a view of the world, I don’t care if they’re a painter or a dustman.”

“Even Jordan, she’s talented in a way,” he continues. “She’s just an ordinary working class girl who did something of absolutely no interest to me whatsoever – but she did something and succeeded, and that interests me. If she hadn’t done that, she’d have had a normal job. So at least she changed her life, and changed some people’s lives around her.”

And, though Bailey is pretty scathing of people who’ve photographed him – “I don’t let them come very often, but when they do they don’t talk. How can you photograph someone if you don’t talk to them? How can they find out if I’m a saint or an arsehole?” – by his own criteria, he’s a more than worthy subject. Obviously talented, he definitely has strong views, and has unquestionably changed his life.

If my first impression was that he was a handful, this interview has only affirmed it – but it’s also made me think that that made him. Through being assertive and refusing to play ball, he was able to carve out a stellar career – when others from the same background could not.

Take one of his key influences early on, a friend called Charlie Papier “who’d been to art school when none of us knew what art school was, and who turned me on to – well, everything really”. There’s a shot Bailey took of him in 1959 – Bailey’s in the frame behind his Rolleiflex, a friend called Daniel O’Connor is playing guitar, and Papier is playing saxophone, wearing shades and looking every inch the cool and charismatic friend.

“He became a taxi driver,” says Bailey, shrugging. “My alternative was that I would have been a bus driver. Nothing wrong with being a bus driver but it didn’t interest me much.”

But when I put this to him, when I point out he’s talented, that he’s contributed the cultural landscape, and that he’s done something remarkable really, he modestly shrugs it off. “I suppose so, but I don’t think about that,” he says. “You won’t do things if you think about them too much.

“If you think about life it’s pretty ridiculous,” he adds, then he fires off another great laugh.

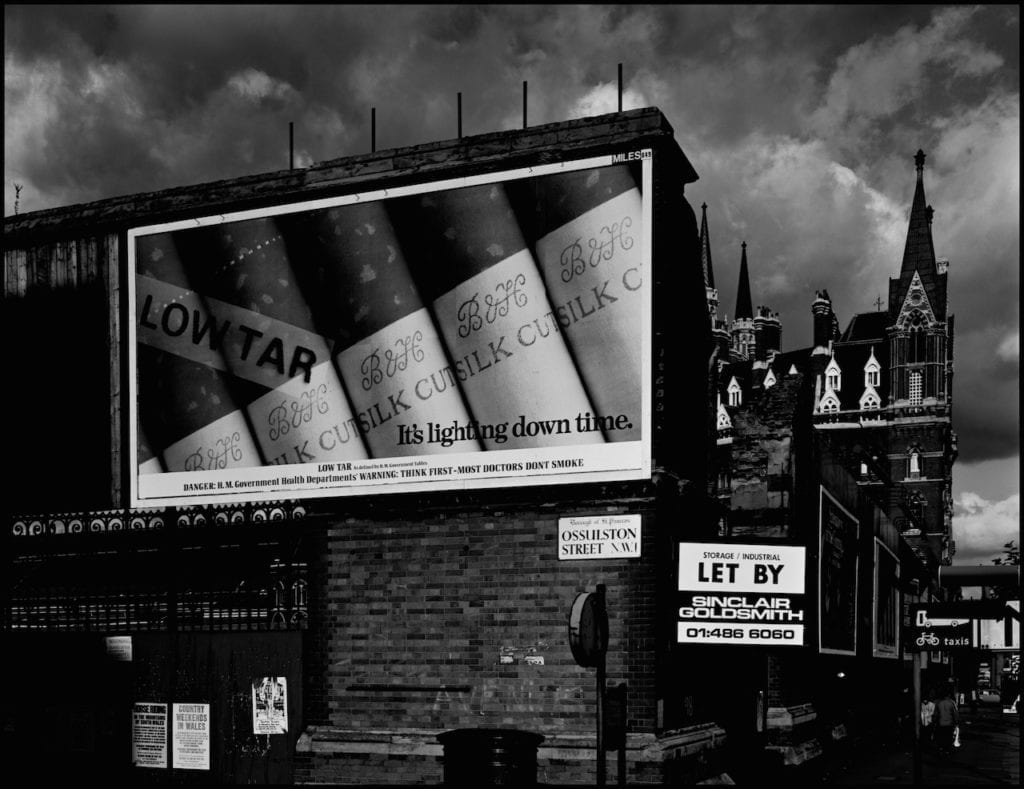

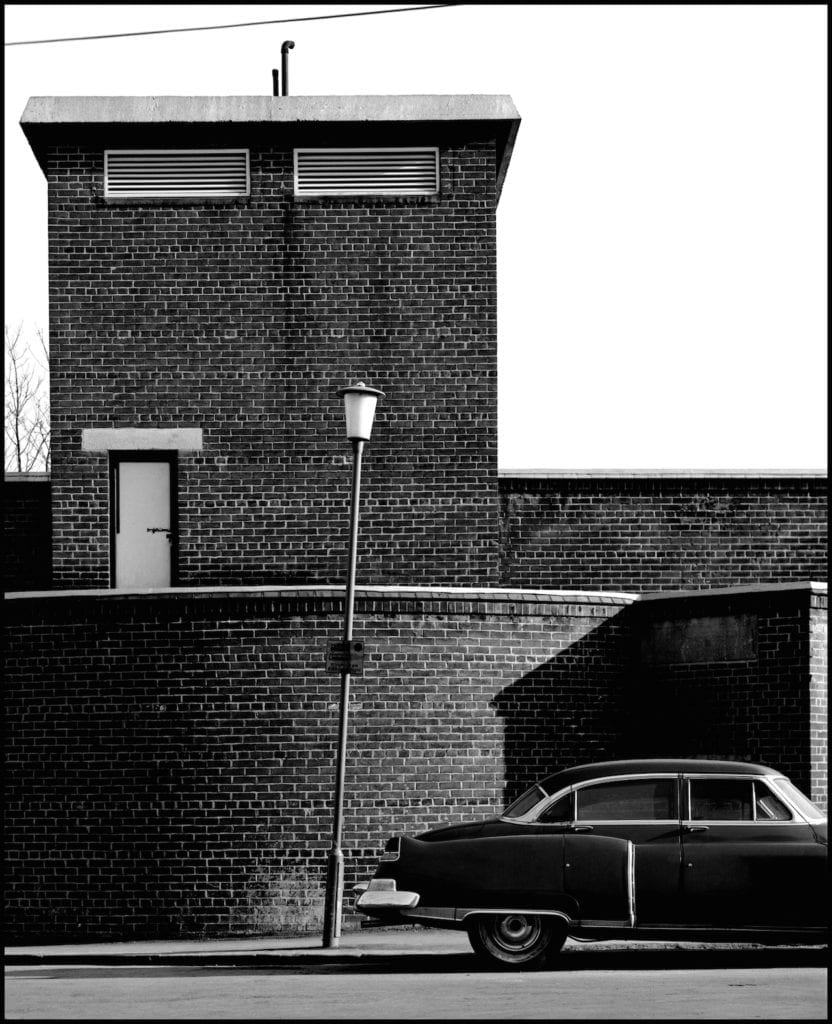

NW1 by David Bailey is published by Heni in a limited edition of 1000, priced £125 each. To win a signed copy, please visit: https://bjp.photo/