“A camera is a sublimation of the gun,” Susan Sontag wrote in her seminal collection of essays On Photography, first published in 1977. “To photograph someone is a subliminal murder – a soft murder, appropriate to a sad, frightened time.” But for Richard Mosse’s latest work, Incoming, his camera wasn’t a sublimation – it was the weapon itself.

The Irishman’s rise has been vertiginous. Graduating from an MRes in cultural studies in 2003, a decade later he was representing his home country at the Venice Biennale, by way of a postgraduate course in fine art at Goldsmiths, an MFA in photography at Yale University and dozens of solo and group exhibitions in between.

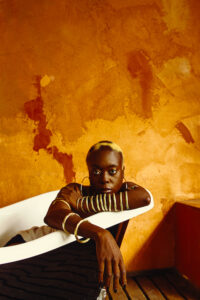

Platon, 2012 © Richard Mosse

But, even as he was welcomed in by Magnum, Mosse privately harboured an increasing sense of disillusionment with documentary photography. He had become frustrated with what he saw as its repetitiveness and its conservatism, the way it makes claims to the truth and to eternal relevance, yet is as authored and considered as any other medium.

Infra continued to be exhibited in galleries all over the world but Mosse himself was rarely heard from. Just as his stock grew, he seemed to mysteriously disappear from the photography community. The 36-year-old never pursued full membership of Magnum, and instead pursued the path he’d begun with his multichannel video installation for Venice.

The result of that two-year hiatus is Incoming, a look at the much-documented migration crisis that is more recognisable as a film than a photography series. Stills from the new work have been shortlisted for the prestigious Prix Pictet and will be the focus of a vast, complex multimedia exhibition now opening at the Barbican’s remarkable Curve gallery, a 2000 sq metre semi-circular space that is given over to installation art on a grand scale.

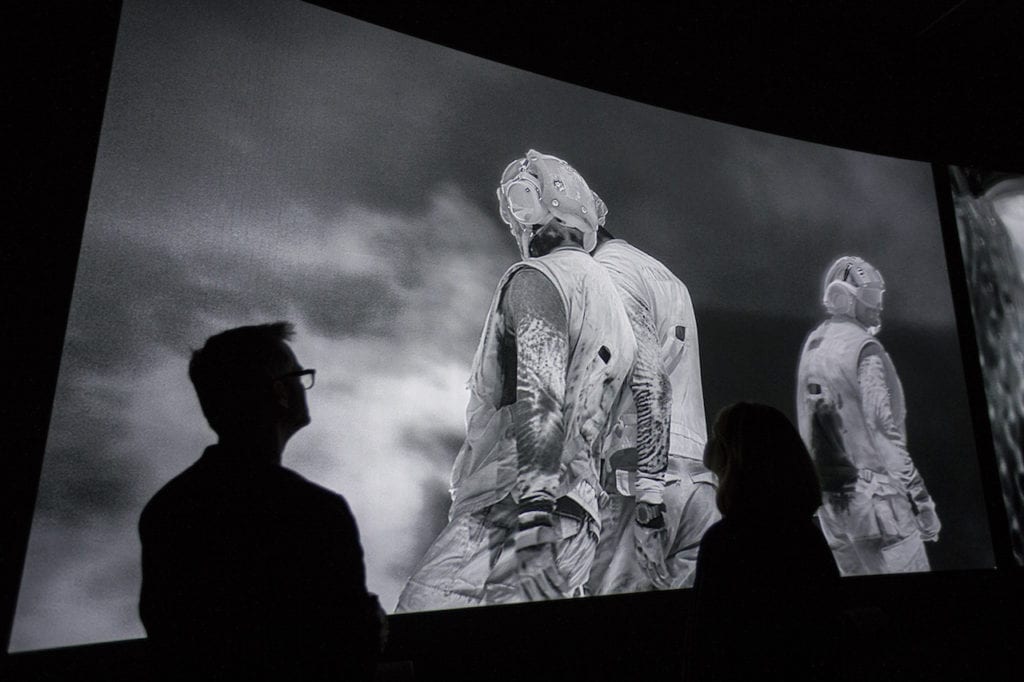

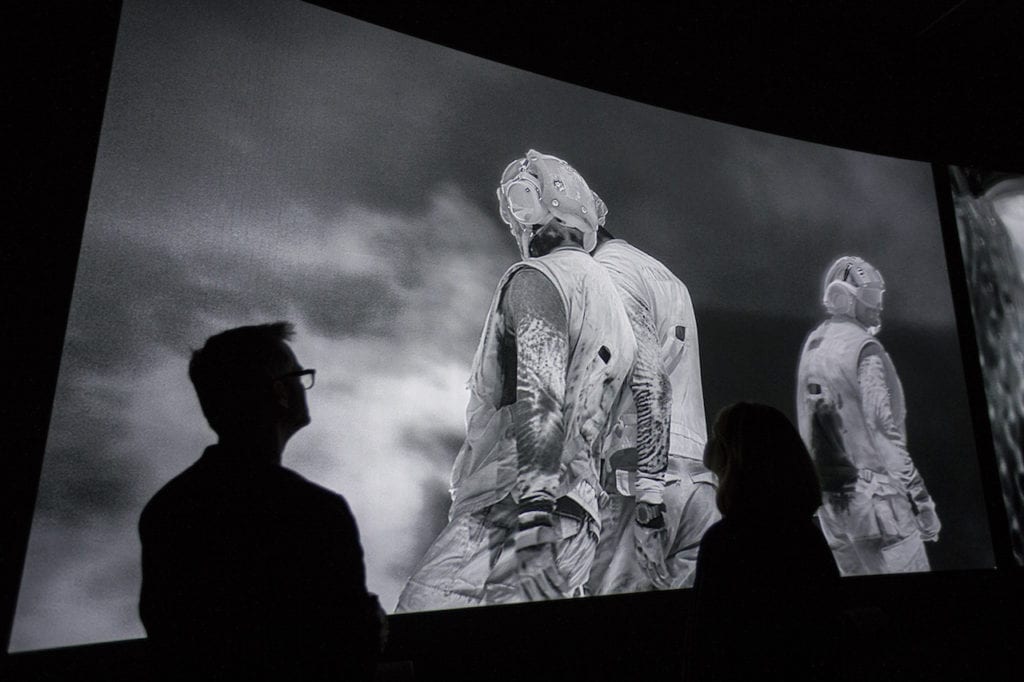

Installation shot of Incoming by Richard Mosse in collaboration with Trevor Tweeten and Ben Frost at The Curve, Barbican. Image © Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for Barbican Art Gallery

In Incoming, Mosse’s ‘camera’ is classified as an advanced weapons system and controlled under the International Traffic in Arms Regulations. He first came across it through a friend working on the BBC’s Planet Earth television series. Using thermographic technology, the device can ‘see’ more than 50km, registering a heat signature as a relative temperature difference.

Patented by the US military, it is normally used in battlefield surveillance, reconnaissance and ballistics targeting, but Mosse has used the weapon against its intended purpose. He has taken something designed to help hunt and kill an enemy and manipulating it to capture and comment on the most pressing subject of our times – the great migration of so many people.

Installation shot of Incoming by Richard Mosse in collaboration with Trevor Tweeten and Ben Frost at The Curve, Barbican. Image © Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for Barbican Art Gallery

Reading heat signatures of people who are completely unaware they’re being caught on camera, Mosse shows us bodies only recognisable through an intense white glow. And so we only recognise them through the context of their landscape – the great stretches of land and sea that surround them, the tent cities, the teeming boats.

Unlike the migrants that have populated our newsfeeds for the past two years, they’re shorn of facial expressions or cultural demarcations – gender, race, age or sex. “The camera I’ve used dehumanises people,” Mosse says. “Their skin glows so they look alien, or monstrous and zombie-like.

“You can see their blood circulation, their sweat, their breath. You can’t see the pupils of their eyes, but a black jelly instead. But, in fact, it allows you to capture portraiture of extraordinary tenderness. We often shot at night, from miles and miles away, so we were shooting people who were not aware of being filmed.

“So we captured some extremely authentic gestures – people asleep, people embracing each other, people at prayer. There’s a stolen intimacy to it. There’s no awareness, there’s no self consciousness. It’s a two-step process – dehumanising them and then making them human again.”

Still frame from Incoming, 2015-2016 © Richard Mosse

The central African region has been the subject of European fascination since long before Joseph Conrad’s fictional voyage up river in Heart of Darkness, published in 1899. Mosse began his own journey in 2012, travelling to the Democratic Republic of Congo on and off over a period of two years during which he documented the “Hobbesian state” of ongoing conflict that has drawn in eight other nations and left millions dead.

Funding the trip from his own meagre resources, he slept in Catholic missions and got a handle on the place by talking to the few correspondents left in Kinshasa. But the more embedded he became in the region, and the more people he spoke to, the less he felt he understood. There are around 30 armed groups in Congo, many of whom form uneasy bonds, truces or mercenary alliances, either with each other or the government forces.

“Many of them used to have an ideology but they’ve long since forgotten it,” Mosse said in an interview with The Telegraph. “They fall into alliances with each other, then renounce them.”

Richard Mosse’s installation The Enclave, 2013 at the Venice Biennale. Image © Tom Powel Imaging inc

The Irishman’s rise has been vertiginous. Graduating from an MRes in cultural studies in 2003, a decade later he was representing his home country at the Venice Biennale, by way of a postgraduate course in fine art at Goldsmiths, an MFA in photography at Yale University and dozens of solo and group exhibitions in between.

But, even as he was welcomed in by Magnum, Mosse privately harboured an increasing sense of disillusionment with documentary photography. He had become frustrated with what he saw as its repetitiveness and its conservatism, the way it makes claims to the truth and to eternal relevance, yet is as authored and considered as any other medium.

Infra continued to be exhibited in galleries all over the world but Mosse himself was rarely heard from. Just as his stock grew, he seemed to mysteriously disappear from the photography community. The 36-year-old never pursued full membership of Magnum, and instead pursued the path he’d begun with his multichannel video installation for Venice.

The result of that two-year hiatus is Incoming, a look at the much-documented migration crisis that is more recognisable as a film than a photography series. Stills from the new work have been shortlisted for the prestigious Prix Pictet and will be the focus of a vast, complex multimedia exhibition now opening at the Barbican’s remarkable Curve gallery, a 2000 sq metre semi-circular space that is given over to installation art on a grand scale.

In Incoming, Mosse’s ‘camera’ is classified as an advanced weapons system and controlled under the International Traffic in Arms Regulations. He first came across it through a friend working on the BBC’s Planet Earth television series. Using thermographic technology, the device can ‘see’ more than 50km, registering a heat signature as a relative temperature difference.

Patented by the US military, it is normally used in battlefield surveillance, reconnaissance and ballistics targeting, but Mosse has used the weapon against its intended purpose. He has taken something designed to help hunt and kill an enemy and manipulating it to capture and comment on the most pressing subject of our times – the great migration of so many people.

Reading heat signatures of people who are completely unaware they’re being caught on camera, Mosse shows us bodies only recognisable through an intense white glow. And so we only recognise them through the context of their landscape – the great stretches of land and sea that surround them, the tent cities, the teeming boats.

Unlike the migrants that have populated our newsfeeds for the past two years, they’re shorn of facial expressions or cultural demarcations – gender, race, age or sex. “The camera I’ve used dehumanises people,” Mosse says. “Their skin glows so they look alien, or monstrous and zombie-like.

“You can see their blood circulation, their sweat, their breath. You can’t see the pupils of their eyes, but a black jelly instead. But, in fact, it allows you to capture portraiture of extraordinary tenderness. We often shot at night, from miles and miles away, so we were shooting people who were not aware of being filmed.

“So we captured some extremely authentic gestures – people asleep, people embracing each other, people at prayer. There’s a stolen intimacy to it. There’s no awareness, there’s no self consciousness. It’s a two-step process – dehumanising them and then making them human again.”

The central African region has been the subject of European fascination since long before Joseph Conrad’s fictional voyage up river in Heart of Darkness, published in 1899. Mosse began his own journey in 2012, travelling to the Democratic Republic of Congo on and off over a period of two years during which he documented the “Hobbesian state” of ongoing conflict that has drawn in eight other nations and left millions dead.

Funding the trip from his own meagre resources, he slept in Catholic missions and got a handle on the place by talking to the few correspondents left in Kinshasa. But the more embedded he became in the region, and the more people he spoke to, the less he felt he understood. There are around 30 armed groups in Congo, many of whom form uneasy bonds, truces or mercenary alliances, either with each other or the government forces.

“Many of them used to have an ideology but they’ve long since forgotten it,” Mosse said in an interview with The Telegraph. “They fall into alliances with each other, then renounce them.”

“By the time photographers arrive there is nothing left to see. It was this lack of trace that interested me, and ultimately the failure of documentary photography. Conflict is complicated and unresolvable and it’s not always easy to find the concrete subject, the issue, and put it in front of the lens.”

Mosse gained access to some of the warring factions that fight nominal government forces but he did so with a custom-built large format camera loaded with Kodak Aerochrome film – an infrared colour camera stock which registers, and then filters out chlorophyll in live vegetation. The stock was developed by Kodak for the US military during the Second World War as a way of identifying camouflaged targets in lush landscapes.

Mosse gained access to some of the warring factions that fight nominal government forces but he did so with a custom-built large format camera loaded with Kodak Aerochrome film – an infrared colour camera stock which registers, and then filters out chlorophyll in live vegetation. The stock was developed by Kodak for the US military during the Second World War as a way of identifying camouflaged targets in lush landscapes.

Pages: 1 2

Never miss a beat with our newsletter

Exhibitions, events, photobooks and all the best articles from every category — register for free now and never miss a beat.