“At the same time it’s the most universal experience and the most unique experience. It transforms the way you view everything.” Like any new father, whose world has just been utterly transformed, Christopher Anderson spent the first two years of his son’s life taking pictures. Lots of pictures. Pictures of him in his mother’s arms, in the bath, asleep, at play.

But not all new fathers are also Magnum photographers. And gradually, without him ever really thinking about them as a project, Anderson’s family album found its way out into the world. Eventually in 2008, after he decided to publish them as body of work in the book, Son, “I realised not only is this part of my work, this is my work.”

Over the past few years we’ve seen other intimate photographs cropping up in group exhibitions and books too – Family Politics at Jerwood Space, Home Truths at the Photographers’ Gallery and books such as Family Photography Now. In two consecutive years, the Taylor Wessing Portrait Prize went to family portraits: David Titlow’s Konrad Lars Hastings Titlow in 2014 and David Stewart’s Five Girls in 2015.

This fascination with the familiar isn’t a new phenomenon, says Phillip Prodger, head of photographs at the National Portrait Gallery and a former judge of the Taylor Wessing Photographic Portrait Prize. “We live in a world of the free exchange of imagery and social media and perhaps the photographs that once were considered more private aren’t considered so private anymore. I think people have been making those photographs all along but perhaps not sharing them in that way.”

Her tutor, David Chandler, seeing her “in bits” suggested she start to photograph closer to home. “I remember thinking, ‘Oh, I don’t have to work in projects, I can just photograph where I go every day and see what happens’.”

Photography, she says, “has this kind of urgency, this concentration about it that means you try to bring all those elements together of light, colour, form, narrative, it’s really complex. So how can I really be fully present with my family?”

“There’s a desperation in that but also a pleasure,” he adds. The dilemma comes when deciding which pictures to put out there. “It’s his life and I’m more conscious about that”.

By contrast, he says, celebrities can be difficult to photograph well. “Photographing Tom Cruise is a bit like photographing the sunset. Making something really different and distinguished with that subject matter is a real challenge.”

A great portrait can be of the Queen or of your mother, but whether it shows a royal or the everyday faces the Portrait of Britain is looking for, it offers the viewer “something they knew already but can’t quite visualise or showing them something they never knew.” – Philip Prodger.

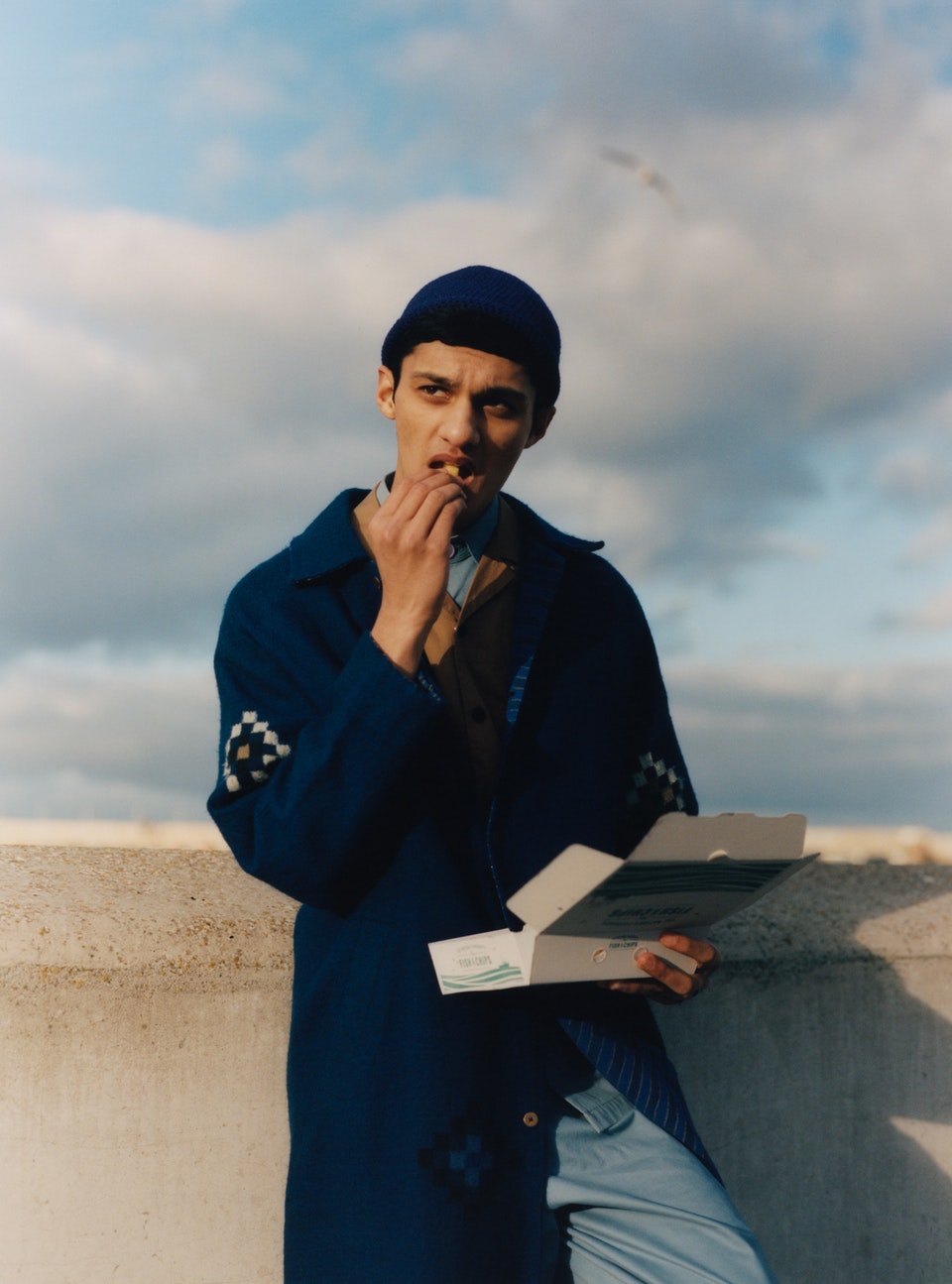

Son has changed how Anderson approaches all photography – whether working on a personal series such as Bleu, Blanc Rouge, which explores French national identity, or a taking a commissioned portrait of Barack Obama for WIRED.

“I’m looking for a way to communicate something of the experience I have with that person whoever that person may be,” he says. “That spark that’s in the pictures of my family is what I want for all my photography.” – Christopher Anderson

Do you shoot portraits of your family – or of your friends, acquaintances or strangers, the ordinary people who populate this country? Enter Portrait of Britain to have your images seen by millions across the UK.

The competition is open until Monday 26th June, 2017.

Portrait of Britain will showcase portraits of you, your family, your friends, your community in public spaces around the country. We’re looking for pictures of ordinary Britons, shot by non-professional, as well as professional photographers.

Visit: portraitofbritain.uk to find out more information about this year’s competition.

Deadline for entries: 26 June 2017.