On the face of it, Thomas Ruff has radically altered course since his first major series brought him to international fame in the mid-1980s. He followed his portraits of fellow students at the Düsseldorf Art Academy (where he was studying photography with the legendary Bernd and Hilla Becher) with photographs of modern architecture in the 1987-1991 series Hauser, and then began working with appropriated images.

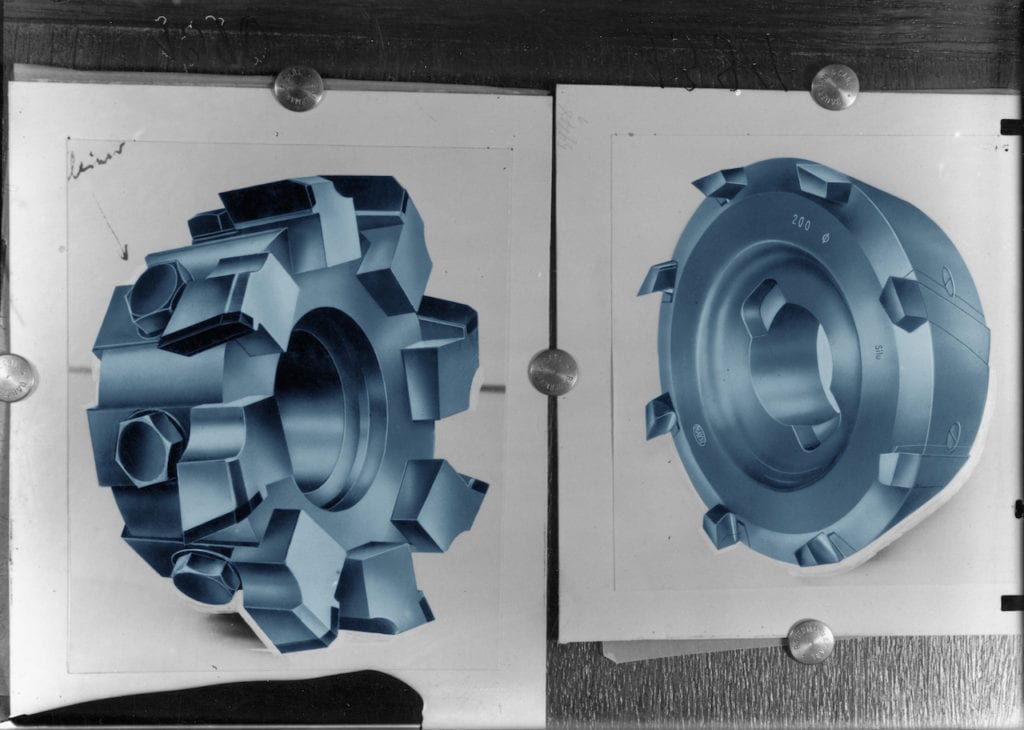

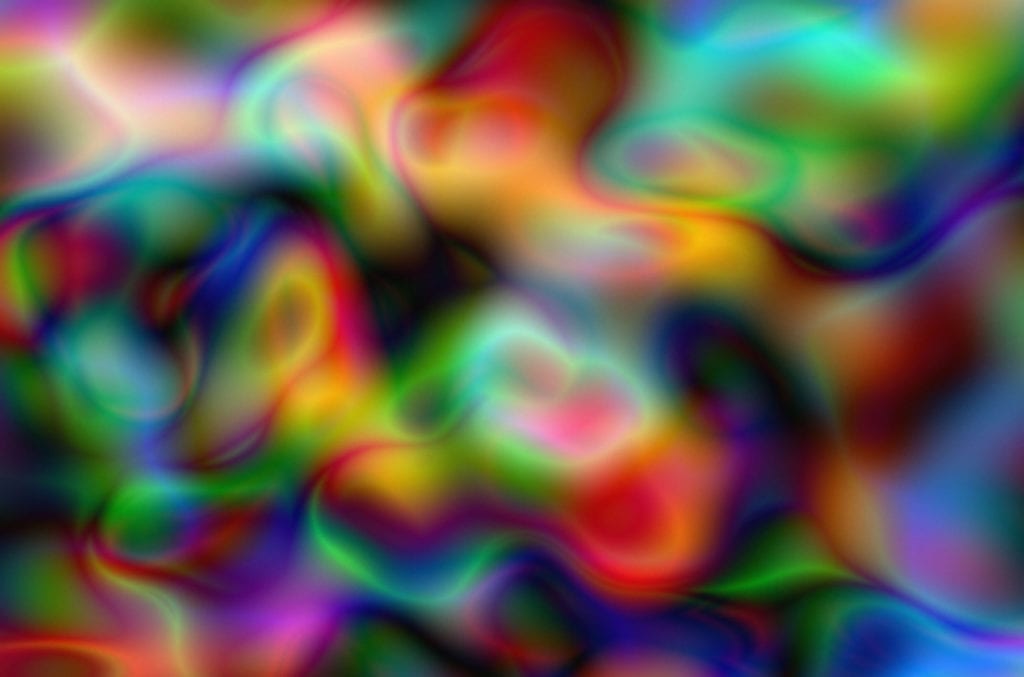

His 1989 series, Sterne, used astronomical panoramas from the European Southern Observatory, for example, while his Zeitungsfotos made during the 1990s took images culled from newspapers. Over the following decade he has continued working with the vernacular, incorporating source material such as manga comics which he manipulated into colourful abstractions (Substrat), highly pixellated images he downloaded from the internet (Jpegs), and an archive of glass negatives found in a factory archive from the 1930s and 40s (Machines).

Maschine 1390 (Machine 1390), 2003 © Thomas Ruff. Image courtesy Whitechapel Gallery, which is showing Thomas Ruff: Photographs 1979 – 2017 from

27 September 2017—21 January 2018

His 1989 series, Sterne, used astronomical panoramas from the European Southern Observatory, for example, while his Zeitungsfotos made during the 1990s took images culled from newspapers. Over the following decade he has continued working with the vernacular, incorporating source material such as manga comics which he manipulated into colourful abstractions (Substrat), highly pixellated images he downloaded from the internet (Jpegs), and an archive of glass negatives found in a factory archive from the 1930s and 40s (Machines).

But while Ruff is happy to admit his techniques change from series to series, the concept behind his work has remained consistent. In an interview for his latest catalogue he told Hans Ulrich Obrist, curator at the Serpentine Gallery in London, that there are three categories to his work: “There is traditional camera-based photography, then there is photography with machines or with optical systems, and finally there is the digitised image.” But each series probes the structure of images, and the ways in which their apparently indexical link with reality are disrupted and disturbed by the medium.

His portraits of fellow students could be described as photographs of portraits as much as they are photographs of people, for example, referencing ID pictures; the subject of his Jpegs series is digital compression as much as the images depict landscapes. As Markus Kramer argued in the 2011 book, Thomas Ruff: Modernism, the 54-year-old artist is methodically undertaking “a modernist analysis of the medium”. As Ruff himself puts it: “The difference between my predecessors and me is that they believed to have captured reality and I believe to have created a picture. We all lost, bit by bit, the belief in this so-called objective capturing of real reality.”

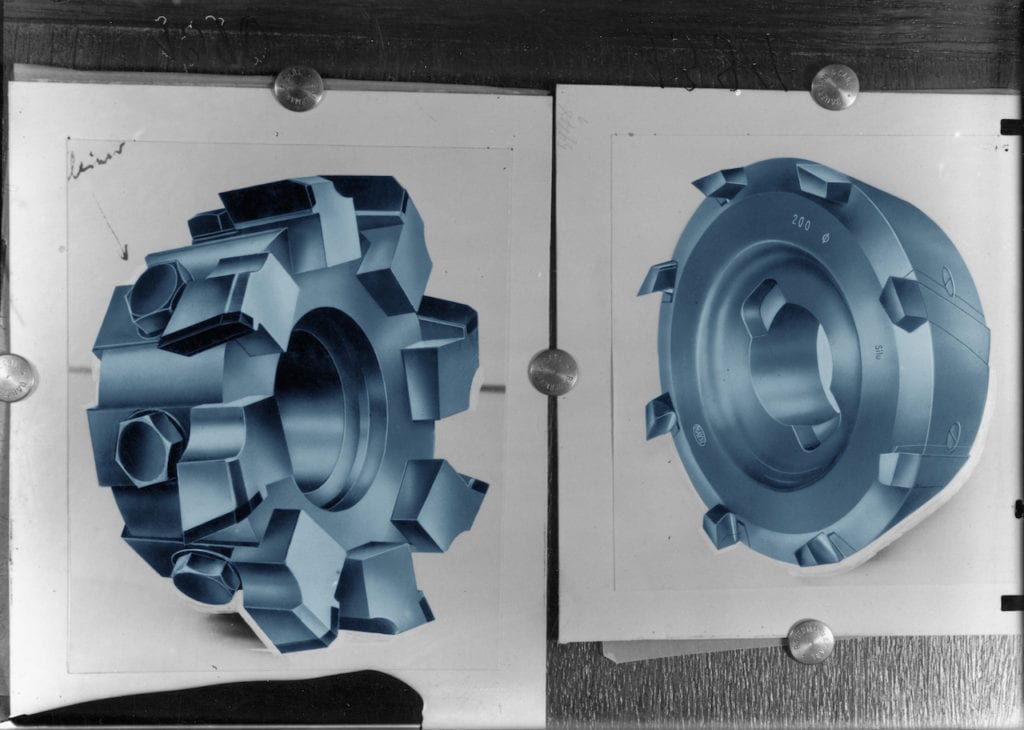

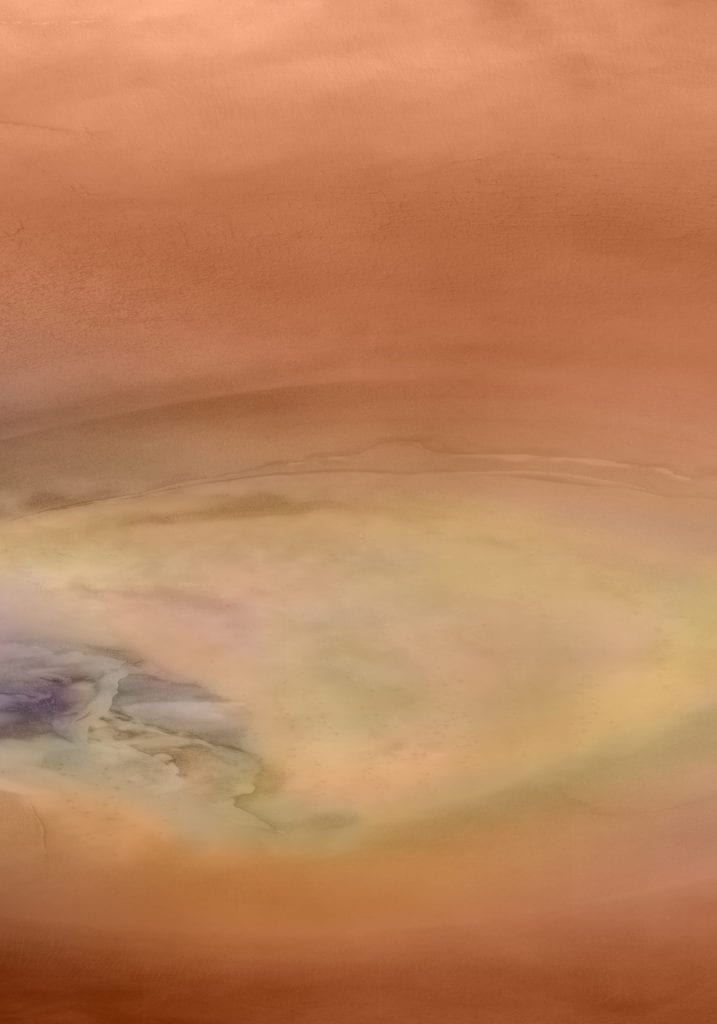

Gagosian Gallery is using this quote on its press release for its first exhibition of Ruff ’s work (it’s showing ma.r.s and nudes at its two London venues), and it’s easy to see why – both series use images appropriated from the internet, and say more about the way images are consumed and disseminated than their ostensible subjects. His nudes are comprised of images of women culled from porn websites, enlarged and processed so that the image breaks down into an impressionistic blur, for example, while ma.r.s is based on images of the Red Planet taken from Nasa’s online archive, which Ruff has coloured according to either scientific extrapolations or his own whim.

nudes lk18, 2000 © Thomas Ruff. Image courtesy Whitechapel Gallery, which is showing Thomas Ruff: Photographs 1979 – 2017 from

27 September 2017—21 January 2018

“I have to confess I did not intend to really blur them, but in my experiments it happened, and then I thought this is an interesting, or beautiful, or painterly, or whatever effect in the image. But I still wanted to have the pixel visible, so I enlarged them so that if you go close to the image you still recognise that you’re looking at a digital file. You recognise it’s not a proper high resolution photograph, it comes from this internet digital world, and that you are looking at a kind of artefact of something artificial produced for desire.

“I’m really not interested in pornography, but there’s a big tradition of nudes in photography, and I wanted to work with that,” he adds. “If you go to these porn pages, there are hundreds of very ugly pictures, but there are some images, which I hope I have picked, that have a pictorial quality in terms of composition, figure, whatever, that are really attractive.”

Nasa’s images are trickier still because although they’re taken by apparently objective remote recording devices, they’re actually painstakingly supplemented by human beings. Most of the images recorded of Mars are actually sent to Earth in black-and-white, because sending colour is too data-heavy. Nasa technicians then “process” the images and add colour. These images may be an accurate depiction of reality, but often they consciously reflect the historic aesthetic of the sublime in landscape painting, creating imagery that is perhaps more sensational to the public – and, no doubt, Nasa’s sponsors. In taking the original monochrome images and colouring them, Ruff is simply re-enacting what always goes on.

“I have to confess I did not intend to really blur them, but in my experiments it happened, and then I thought this is an interesting, or beautiful, or painterly, or whatever effect in the image. But I still wanted to have the pixel visible, so I enlarged them so that if you go close to the image you still recognise that you’re looking at a digital file. You recognise it’s not a proper high resolution photograph, it comes from this internet digital world, and that you are looking at a kind of artefact of something artificial produced for desire.

“I’m really not interested in pornography, but there’s a big tradition of nudes in photography, and I wanted to work with that,” he adds. “If you go to these porn pages, there are hundreds of very ugly pictures, but there are some images, which I hope I have picked, that have a pictorial quality in terms of composition, figure, whatever, that are really attractive.”

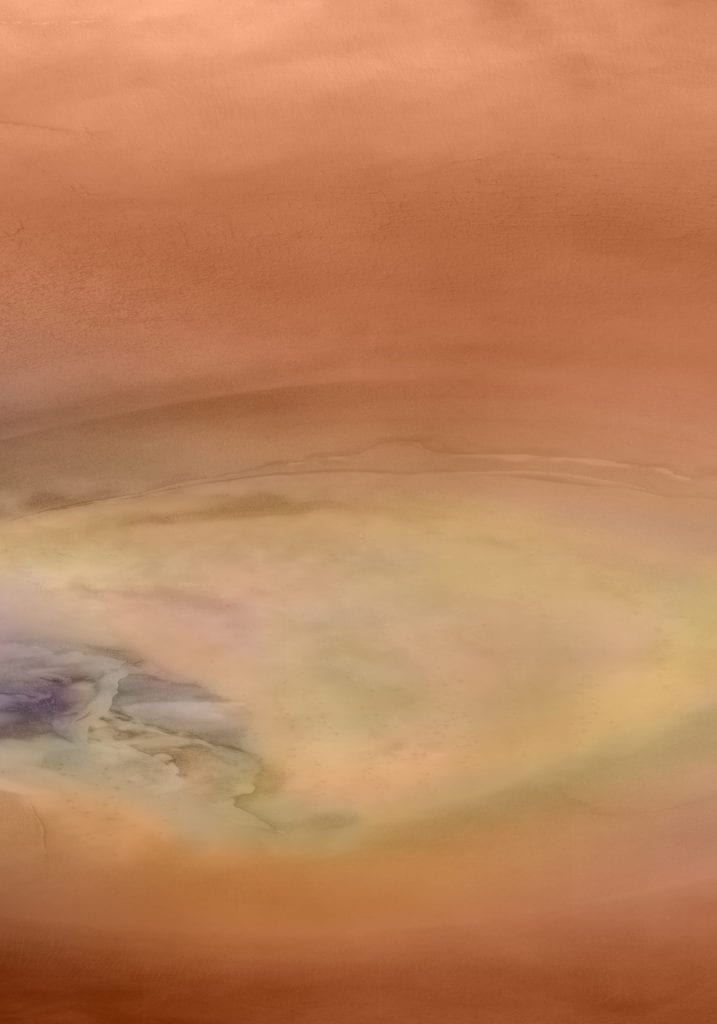

Nasa’s images are trickier still because although they’re taken by apparently objective remote recording devices, they’re actually painstakingly supplemented by human beings. Most of the images recorded of Mars are actually sent to Earth in black-and-white, because sending colour is too data-heavy. Nasa technicians then “process” the images and add colour. These images may be an accurate depiction of reality, but often they consciously reflect the historic aesthetic of the sublime in landscape painting, creating imagery that is perhaps more sensational to the public – and, no doubt, Nasa’s sponsors. In taking the original monochrome images and colouring them, Ruff is simply re-enacting what always goes on.

“When I started working on those images I asked Nasa why they don’t take colour photographs, and they responded that it’s a problem of getting the data back down to earth,” Ruff explains. “They have preview images in colour, so I asked, ‘Are those images Photoshopped?’, and they said ‘No, they’re processed,’ whatever that means. Even they don’t know the truth in colour – it’s just a kind of ‘probably’.

“The Nasa camera does capture small areas in infra-red and RGB, so they use swaps [to extrapolate those areas onto a larger image], or statistics, or what the scientists say, but you cannot be sure that colours are true. To make those images not look too strange they look at oil paintings, and give them colours that are real or familiar.

“So that’s what I do with the ma.r.s images,” he continues. “Sometimes I’m looking at these swaps and I colour the whole image, but sometimes I say ‘coloured space is nonsense’ and I do as I want. I work more or less intuitively – I don’t have a vision of Mars. It’s more playing around, experimenting with colours, and what could fit with this kind of surface. The impact craters have to be more dark and sand dunes have to be more shiny, for example.”

ma.r.s. 01_III, 2011 © Thomas Ruff. Image courtesy Whitechapel Gallery, which is showing Thomas Ruff: Photographs 1979 – 2017 from

27 September 2017—21 January 2018

“The Nasa camera does capture small areas in infra-red and RGB, so they use swaps [to extrapolate those areas onto a larger image], or statistics, or what the scientists say, but you cannot be sure that colours are true. To make those images not look too strange they look at oil paintings, and give them colours that are real or familiar.

“So that’s what I do with the ma.r.s images,” he continues. “Sometimes I’m looking at these swaps and I colour the whole image, but sometimes I say ‘coloured space is nonsense’ and I do as I want. I work more or less intuitively – I don’t have a vision of Mars. It’s more playing around, experimenting with colours, and what could fit with this kind of surface. The impact craters have to be more dark and sand dunes have to be more shiny, for example.”

Ruff has even translated some of the ma.r.s pictures into 3D, making anaglyph images that can be viewed with stereoscopic red and green glasses. This again follows Nasa’s approach, as the organisation is using anaglyph techniques to try to map the terrain, but as Ruff told Obrist in the interview for the Gagosian catalogue, the 3D glasses are also humorously incongruent.

“The ma.r.s photographs are both realistic and fictional, and the 3D images add an aspect of the absurd, in the fact that you can actually recognise deep relief on the surface of another planet with cheap 3D glasses.”

Kramer has argued that appropriating images helps Ruff draw attention to the materiality of pictures, writing in his introduction to his book that doing so accentuates “the conceptual knowledge gain, since it is not the ‘artistic’ picture, but the structures and characteristics of the medium itself that come into focus”. Ruff, for his part, says appropriating images allows him to investigate contemporary photographic practice, in an era where images are more numerous, and more easily shared, than ever before. He started his nudes in 1999, for example, just as the internet was coming into more widespread usage, bringing online pornography into the mainstream.

“The ma.r.s photographs are both realistic and fictional, and the 3D images add an aspect of the absurd, in the fact that you can actually recognise deep relief on the surface of another planet with cheap 3D glasses.”

Kramer has argued that appropriating images helps Ruff draw attention to the materiality of pictures, writing in his introduction to his book that doing so accentuates “the conceptual knowledge gain, since it is not the ‘artistic’ picture, but the structures and characteristics of the medium itself that come into focus”. Ruff, for his part, says appropriating images allows him to investigate contemporary photographic practice, in an era where images are more numerous, and more easily shared, than ever before. He started his nudes in 1999, for example, just as the internet was coming into more widespread usage, bringing online pornography into the mainstream.

“What I always want to do is comment on the state of where photography is right now,” he says. “So if the structure of photography changes from grain to pixel, yes I will make a research on the structure of the image. But if you have the pixel as the smallest element the construction of a picture, you also have [the fact that] if you compress the image you can send it easily out into the world via email. So we have the distribution too. We not only have the structure of the image, there are several issues to pull out. That’s one of the things I want to make obvious or visible.”

jpeg ny01, 2004 © Thomas Ruff. Image courtesy Whitechapel Gallery, which is showing Thomas Ruff: Photographs 1979 – 2017 from

27 September 2017—21 January 2018

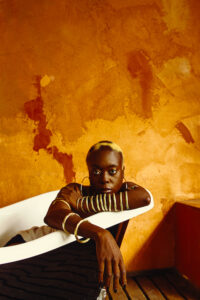

“This situation in Germany and the knowledge of surveillance then made me find the form for the portraits,” he says. “The look of my portraits is the look back into Big Brother’s camera – that’s why the people look so cold and don’t show any emotion, and will definitely not reveal what they are thinking.”

“This situation in Germany and the knowledge of surveillance then made me find the form for the portraits,” he says. “The look of my portraits is the look back into Big Brother’s camera – that’s why the people look so cold and don’t show any emotion, and will definitely not reveal what they are thinking.”

The stark, even lighting of the portraits also referenced the era, he adds, pointing out that his generation grew up in a society with the ability and the political will to light streets brightly so they could be monitored by surveillance cameras. “I definitely did not want to make nostalgic portraits,” he concludes. “I wanted them to be from that time and the situation of that time, which was Western-industrialised society.”

Not only that, but photography was also a natural choice for him and other artists of his generation, he says, because he grew up with newspapers and magazines. “For the next generation, with Youtube, the next thing will be to think, ‘I can pick up my phone and do some clips’,” he says.

Even so, he believes photography is a particularly interesting medium because of its indexicality, and the fact that viewers often confuse it with reality. When he exhibited Portraits he had to print them at monumental size to make people think of them as images, not actual portraits, he says – or as he puts it, to make people say to think, “This is a big photograph of Hans”, not, “This is Hans”.

Nacht 9 II (Night 9 II), 1992 © Thomas Ruff. Image courtesy Whitechapel Gallery, which is showing Thomas Ruff: Photographs 1979 – 2017 from

27 September 2017—21 January 2018

Not only that, but photography was also a natural choice for him and other artists of his generation, he says, because he grew up with newspapers and magazines. “For the next generation, with Youtube, the next thing will be to think, ‘I can pick up my phone and do some clips’,” he says.

Even so, he believes photography is a particularly interesting medium because of its indexicality, and the fact that viewers often confuse it with reality. When he exhibited Portraits he had to print them at monumental size to make people think of them as images, not actual portraits, he says – or as he puts it, to make people say to think, “This is a big photograph of Hans”, not, “This is Hans”.

Ruff ’s formal experimentation shouldn’t be emphasised at the expense of his subjects, though – from modernist buildings to porn actresses, his series have particular, systematically researched subjects. When collecting porn images he tried to amass a comprehensive range of sexual practices, for example, and when photographing German art students, he felt compelled to shoot more than 50 of them.

“If I have the mission of explaining to an extra-terrestrial visitor, I cannot do one photograph because I would then have only men or women,” he says. “So you have to do at least two, and then I think men and women are so individual that even the two is not enough, you have to show more. And in a way the more you show the more you can recognise or look at, and that’s a kind of principle I always follow.”

As Kramer puts it, Ruff doesn’t just investigate the medium of photography, he explores the boundary between the photography and its indexicality, always presenting “the medium’s basic, indexical character in a visually or intellectually comprehensible fashion, thereby securing his works against the arbitrariness that would result from abandoning this indexical frame of reference”.

Haus Nr.11 III, 1990 © Thomas Ruff. Image courtesy Whitechapel Gallery, which is showing Thomas Ruff: Photographs 1979 – 2017 from

27 September 2017—21 January 2018

“If I have the mission of explaining to an extra-terrestrial visitor, I cannot do one photograph because I would then have only men or women,” he says. “So you have to do at least two, and then I think men and women are so individual that even the two is not enough, you have to show more. And in a way the more you show the more you can recognise or look at, and that’s a kind of principle I always follow.”

As Kramer puts it, Ruff doesn’t just investigate the medium of photography, he explores the boundary between the photography and its indexicality, always presenting “the medium’s basic, indexical character in a visually or intellectually comprehensible fashion, thereby securing his works against the arbitrariness that would result from abandoning this indexical frame of reference”.

“I would say the subject is very important, but the reflection on media is also very important,” says Ruff. “In the portraits I’d think sometimes, ‘It’s 60 percent about Hans, and 40 percent about reflection’, and the next day I’d think, ‘Oh maybe it’s only 30 percent about Hans’. In the end you cannot make this decision on what is it about, and I like that.

“Photography is at the same time transparent and the opposite. It’s working in both ways, and it depends on what you want to see or what you look at. In a way, photographs are all mirrors for the person who is looking.”

Thomas Ruff: Photographs 1979-2017 is on show at the Whitechapel Gallery from 27 September 2017-21 January 2018 www.whitechapelgallery.org This interview originally appeared in the April 2012 issue of BJP, which is available via www.thebjpshop.com

press++21.11, 2016 © Thomas Ruff. Image courtesy Whitechapel Gallery, which is showing Thomas Ruff: Photographs 1979 – 2017 from

27 September 2017—21 January 2018

phg.07_II, 2014 © Thomas Ruff. Image courtesy Whitechapel Gallery, which is showing Thomas Ruff: Photographs 1979 – 2017 from

27 September 2017—21 January 2018

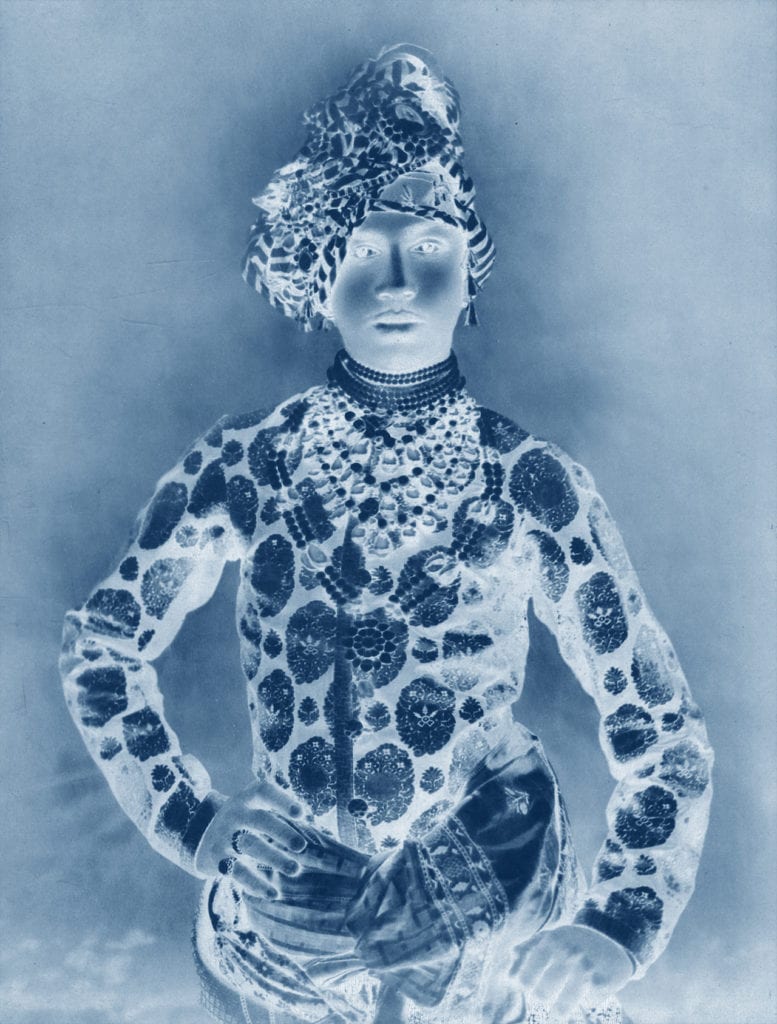

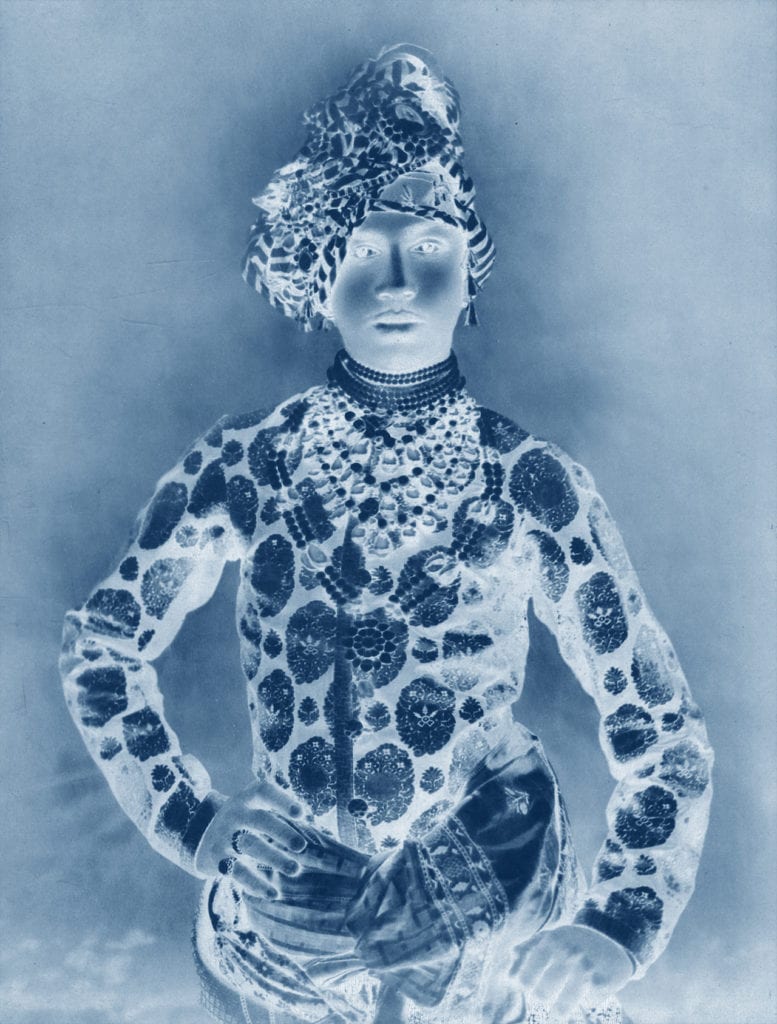

neg◊india_01, 2014 © Thomas Ruff. Image courtesy Whitechapel Gallery, which is showing Thomas Ruff: Photographs 1979 – 2017 from

27 September 2017—21 January 2018

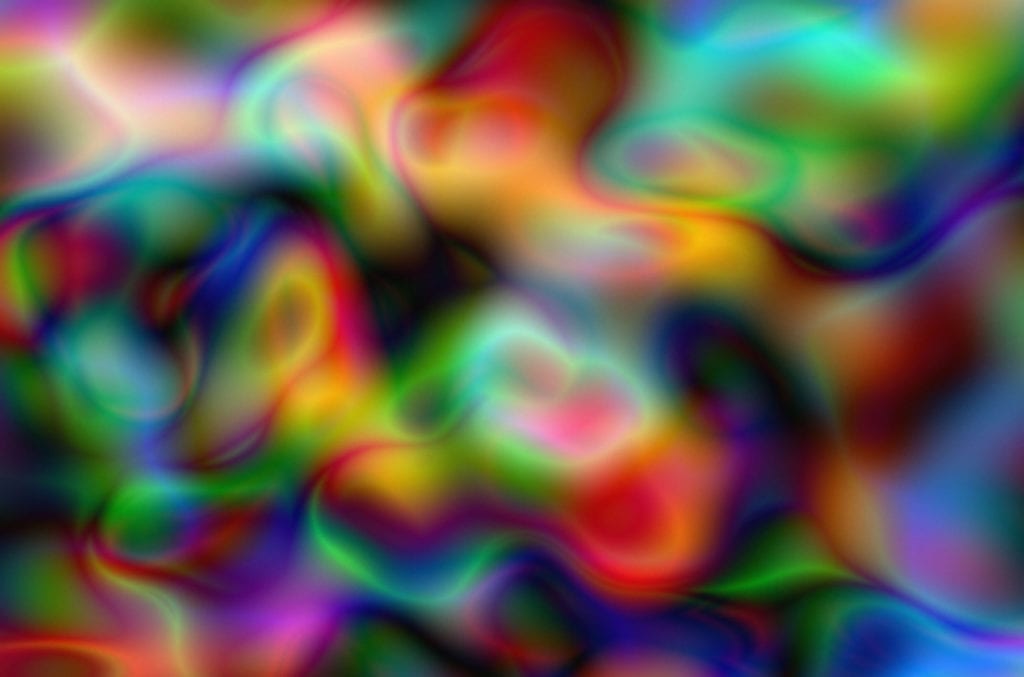

Substrat 31 III, 2007 © Thomas Ruff. Image courtesy Whitechapel Gallery, which is showing Thomas Ruff: Photographs 1979 – 2017 from

27 September 2017—21 January 2018

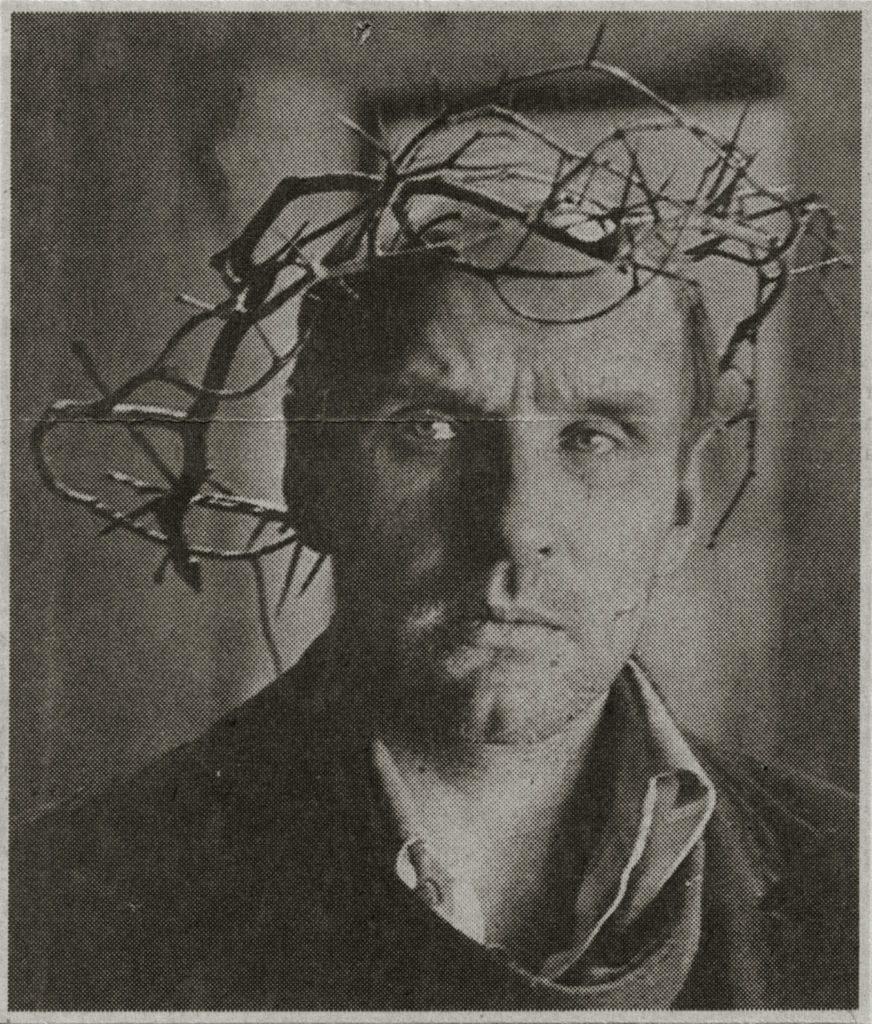

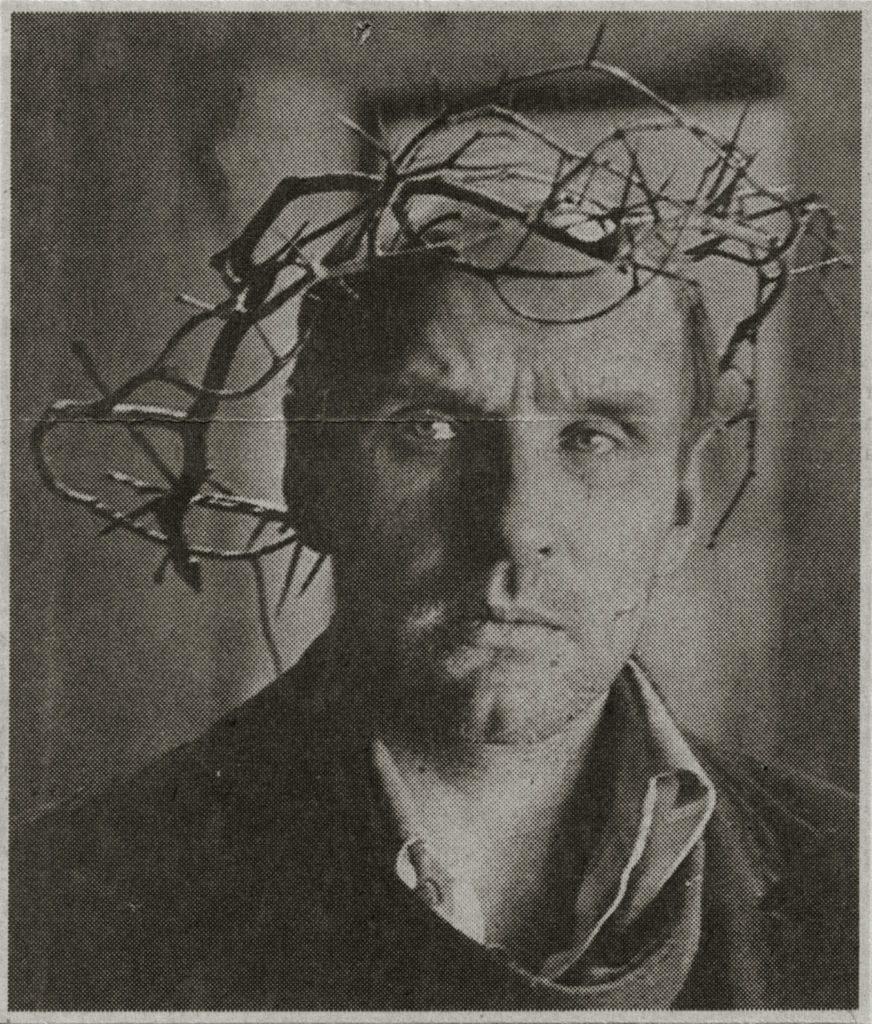

Zeitungsfoto 101 (Newspaper Photograph 101), 1990 © Thomas Ruff. Image courtesy Whitechapel Gallery, which is showing Thomas Ruff: Photographs 1979 – 2017 from

27 September 2017—21 January 2018

16h 30m / -50°, 1989 © Thomas Ruff. Image courtesy Whitechapel Gallery, which is showing Thomas Ruff: Photographs 1979 – 2017 from

27 September 2017—21 January 2018

L’Empereur 06 (The Emperor 06), 1982 © Thomas Ruff. Image courtesy Whitechapel Gallery, which is showing Thomas Ruff: Photographs 1979 – 2017 from

27 September 2017—21 January 2018

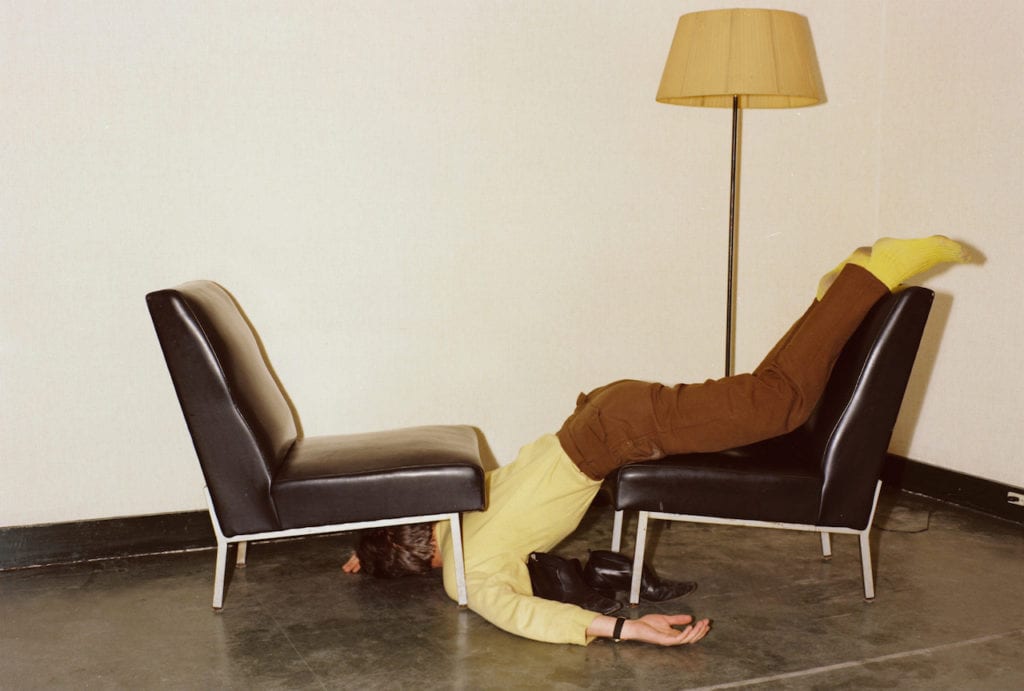

Interieur 1A (Interior 1A), 1979 © Thomas Ruff. Image courtesy Whitechapel Gallery, which is showing Thomas Ruff: Photographs 1979 – 2017 from

27 September 2017—21 January 2018

“Photography is at the same time transparent and the opposite. It’s working in both ways, and it depends on what you want to see or what you look at. In a way, photographs are all mirrors for the person who is looking.”

Thomas Ruff: Photographs 1979-2017 is on show at the Whitechapel Gallery from 27 September 2017-21 January 2018 www.whitechapelgallery.org This interview originally appeared in the April 2012 issue of BJP, which is available via www.thebjpshop.com