“If you’re making work from any community that you’re not a part of yourself, it’s never going to be the perfect representation of them,” says Cian Oba-Smith. “I think one of the biggest problems for the black community and social minorities in general is that they are portrayed in stereotypical ways, be that as violent or otherwise. Black people in the media in America are so often there because either they’ve been shot, or shot someone, or they are a rapper.

“There are a lot of white people who make work around black people’s culture and sometimes the way they present that can be exploitative. If you have a group that is always represented from the outside it’s difficult to get a rounded view. If white Europeans make work about Africa and no Africans are included, how can that be an honest portrayal of that place?”

It’s a pertinent question for Oba-Smith because, though mixed-race and from London, he recently travelled to North Philadelphia to photograph a group of black horsemen. Working towards the end of 2016, a time of huge political change for the US in the run-up to the election of Donald Trump in January 2017, he spent several weeks with the riders getting to know them and their world, in a bid to outrun this kind of cultural appropriation.

The horsemen had captured Oba-Smith’s imagination because they cut across the image of that huge American icon – the cowboy. Now exemplified by figures such as Clint Eastwood or Marlboro Man, horsemen in the US were actually traditionally black, dating back to the time when they cared for animals under slavery. Many of the early winners of the Kentucky Derby were black, thanks to their experience of training and keeping the animals.

“Everyone thinks of the cowboy as this white American hero who has come to slay Native Americans,” says Oba-Smith. “Actually the word cowboy is a racist term. It comes from when slave masters called all their slaves ‘boys’ and so the cow boy was the man or boy who looked after the cows, and the horse boy was the man or boy who looked after the horses. It’s just been reshaped through cinema so it doesn’t have that connotation anymore.

“That’s part of the reason I called the project Concrete Horsemen instead of Concrete Cowboys, because I didn’t want it to tie into that narrative.”

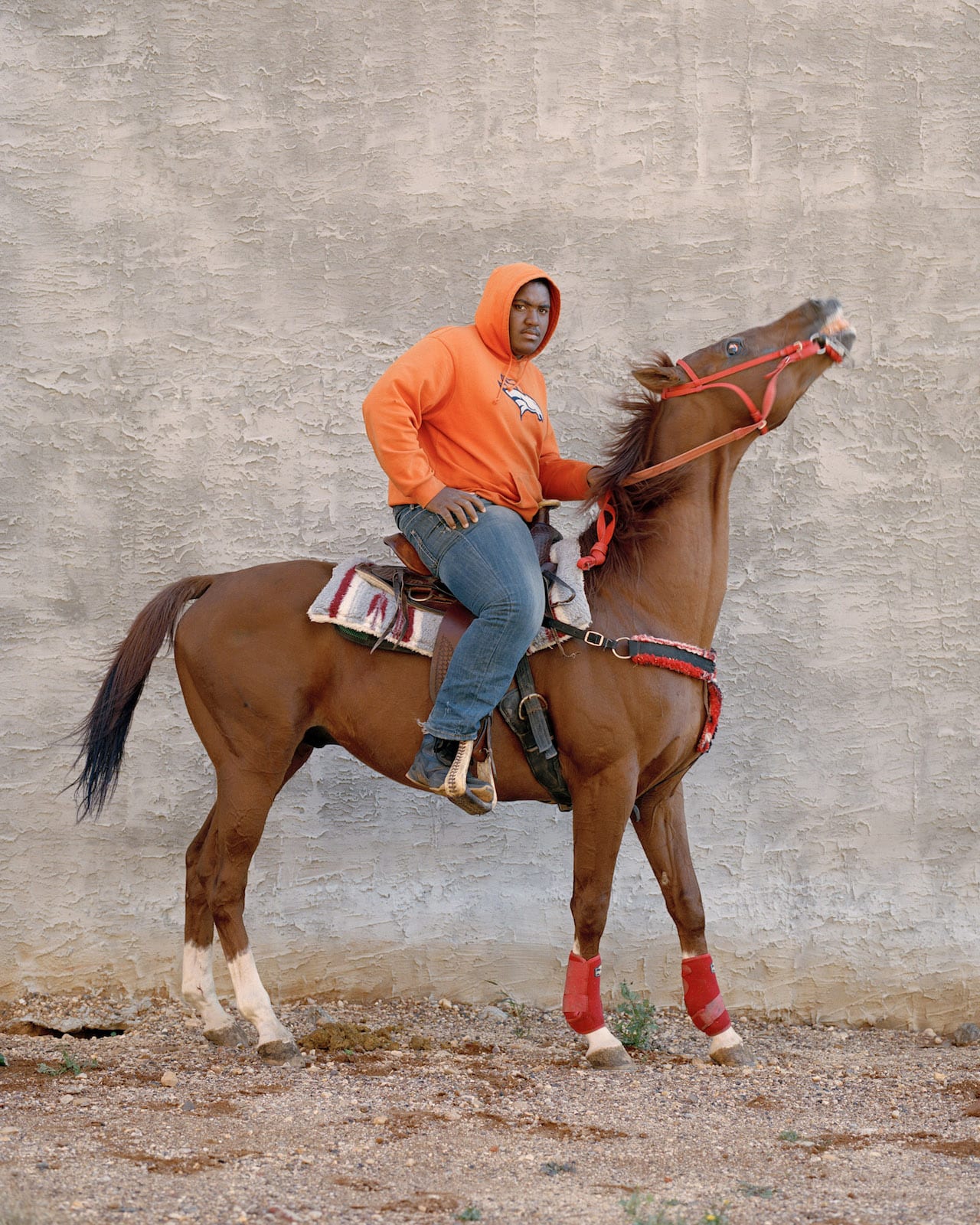

The series is a set of portraits, each focusing in on a particular horseman, his style and his background. But entering the BJP‘s Breakthrough Awards in 2017, Oba-Smith opted to enter the graduate single image category, with a shot of one of the men he’d become closest to in his work (shown in the main pic).

“The younger guys tended to be more interested in where you were from and things like that; I hung out with him quite a lot, so I decided to take a picture,” he says of the shot, which was shortlisted for the BJP prize. “He was busy arranging his stable before the evening and I was worried about the light going. Obviously when you’re working with a bunch of people who don’t know too much about photography, you are waiting and hoping you will be able to take the picture.

“Fortunately, he got everything together and went for a ride and I followed him around. We stopped there and made that portrait just because the light was like that. The sun was setting and it was all in the moment.”