“Her project talks about the identity that the state wants women to project in public,” says Vivienne Gamble, director of Seen Fifteen and now guest curator of the show Catharsis for Belfast Exposed. “She comes from a family where they didn’t have those rules behind closed doors at home. She was conflicted about having this public-facing image, and this different, much more relaxed and liberal, private existence.”

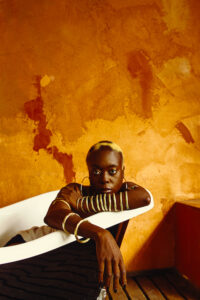

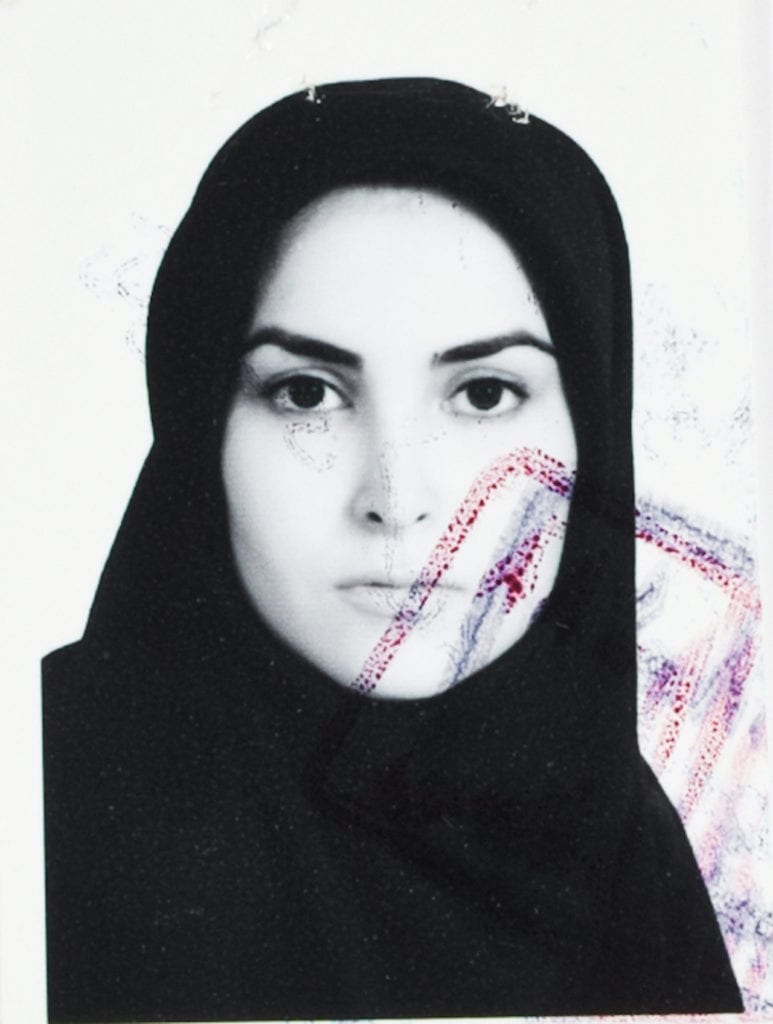

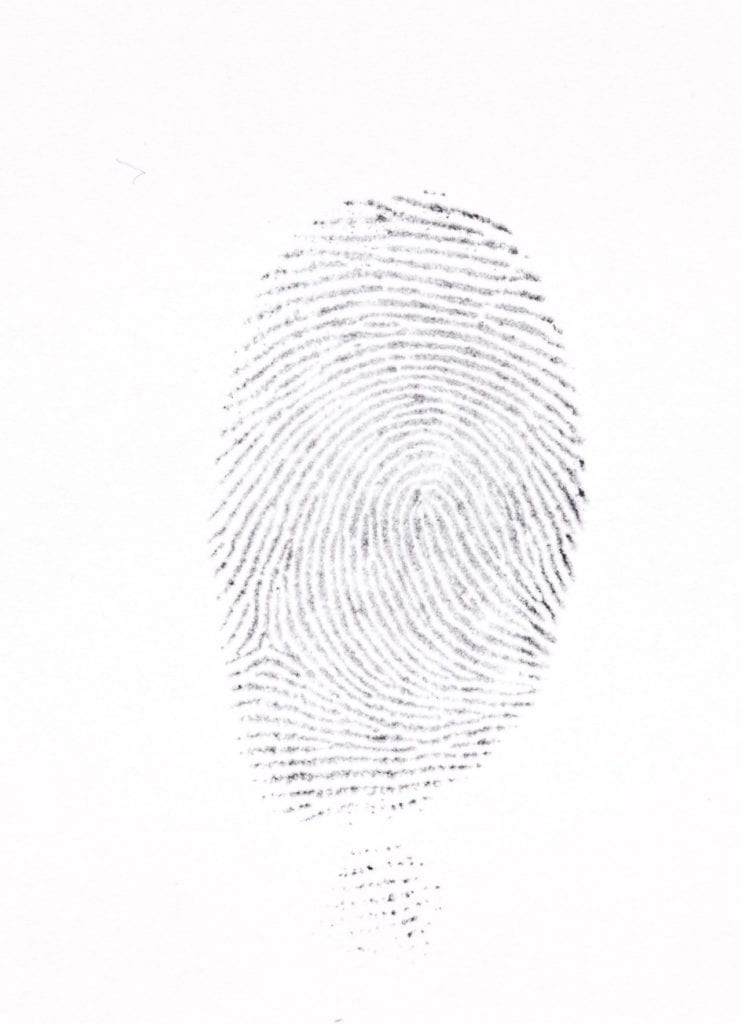

She’s talking about Shenasmenah, a project by Iranian-born photographer, filmmaker and curator Amak Mahmoodian included in the three-person Catharsis show. Held in a “tiny, delicate and beautiful” book wrapped in a headscarf, it’s a collection of portrait photographs and fingerprints from Iranian women’s birth certificates (also known as Shenasmenah). These portraits must be kept updated throughout each woman’s life but always comply with state imposed standards for her appearance – hair must be covered, for example, and almost no make up may be worn. For Mahmoodian, they signified a rift she felt compelled to explore.

“By asking other women to give her their portraits from the Shenasnameh, she entered into a dialogue with them and listened to each of their stories,” explains Gamble. “It became not just about her identity but the identity of many women. It made the project really immense, and required that she take a big personal risk. It’s not only an emotional process in processing her own upbringing and the public versus private conflict there, but also the fear of returning to her home country. It required a lot of bravery.”

“They have each stuck to their gut instincts that these are stories that need to be told,” says Gamble. “All three of them are, in their own ways, showing real courage in these projects.”

Sancari was just 14 when her father died and neither she nor her twin sister were allowed to see his body, partly because of Jewish customs surrounding suicide. The experience left her with an unresolved grief for a long time so, returning to it years later, she used newspaper ads to find men who would have been her father’s age, set up impromptu photo studios outside, and photographed them.

“She’s trying to understand her father and what kind of a man he was,” says Gamble. “She wanted to understand how he might have aged, what kind of life he might have had. She asked the men to put on some of his clothes. It brought ghostliness to the project.”

“By using this correction fluid on top of the photographs, she is trying to understand what this couple were going through,” Gamble explains. “She was trying to get into Ken’s mind and imagine what he was thinking when taking those beautiful photos of Hazel, out in public in that dress, knowing that he perhaps would have wanted to be in her place, in that same dress, behaving as he truly felt in public.”

“Davidmann has also taken photos of the archived bundles of letters themselves,” Gamble continues. “They’re poignant in their own way once you know the story of what’s inside them and what unfolds. Ultimately it’s a love story. At the end of the book there’s a very sad letter written by Ken to Hazel from a few years before they died, where Ken says that if they could turn back the clock and know everything about what their marriage would be, he would still marry her because on a personal level, despite everything, he was still very much in love with her.”

Given the series on show, Catharsis was a natural title for the exhibition – and Belfast Exposed seems a natural home for it too, given that one of the gallery’s founding principles was to tell “true stories from people who understand something the rest of us might not”. “We want people to go on the same emotional journey as the artists did,” says Gamble.

“Hopefully you’ll walk away with a broader understanding of people, areas, and customs you might not have understood before. To know that the version of a person you see walking down the street always has their own story.”

Catharsis is on show at Belfast Exposed from 27 October – 23 December 2017 www.belfastexposed.org https://seenfifteen.com/