“There are two important things about this show,” says Clément Chéroux, senior curator of photography at SFMOMA. “First, the quantity of work – more than 300 photographs, quite a large selection, because we were able to get support from most of the big institutions – MOMA, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Gallery of Canada, the Musée du Quai Branly and so on, and private collections from around the world.

“Second, is the fact that it is arranged thematically rather than chronologically. Usually when you look at important retrospectives they are chronological, but we organised by theme because we wanted to organise it around Evans’ passion for the vernacular. He was fascinated with vernacular culture.”

It is, as Chéroux says, a huge show – the first to take up the SFMOMA’s entire Pritzker Center for Photography, which, at over 1000 square meters, is America’s largest photography gallery. But though a retrospective of this size is entirely appropriate for one of the 20th century’s key photographers, what’s emphasised isn’t his monumental importance or his ongoing influence. Instead it hones in on his love for the more humble and everyday.

“Vernacular cuts to the heart of his research,” says Chéroux by phone from San Francisco. “The idea of the vernacular was Evans’ main goals, and his main task was to try to define through photography what this idea of the vernacular was. The fact that he did it throughout his whole life is so interesting, and makes him unique.”

“Even when he was working for the FSA, he was photographing roadside stands and signs,” he continues. “He wasn’t the only photographer interested in that in the 1930s, but he was the one doing it with a higher level of interest – out of a kind of obsession. And where other photographers explored it and then stopped, Evans continued. He was still doing it at the end of his life.”

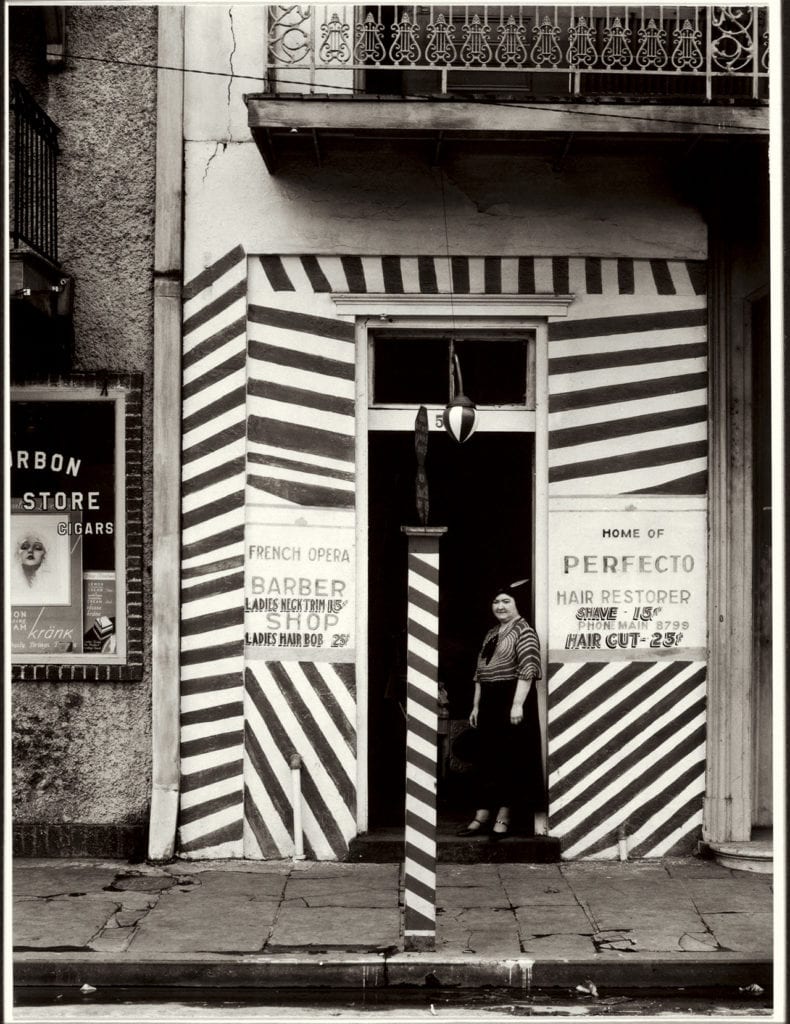

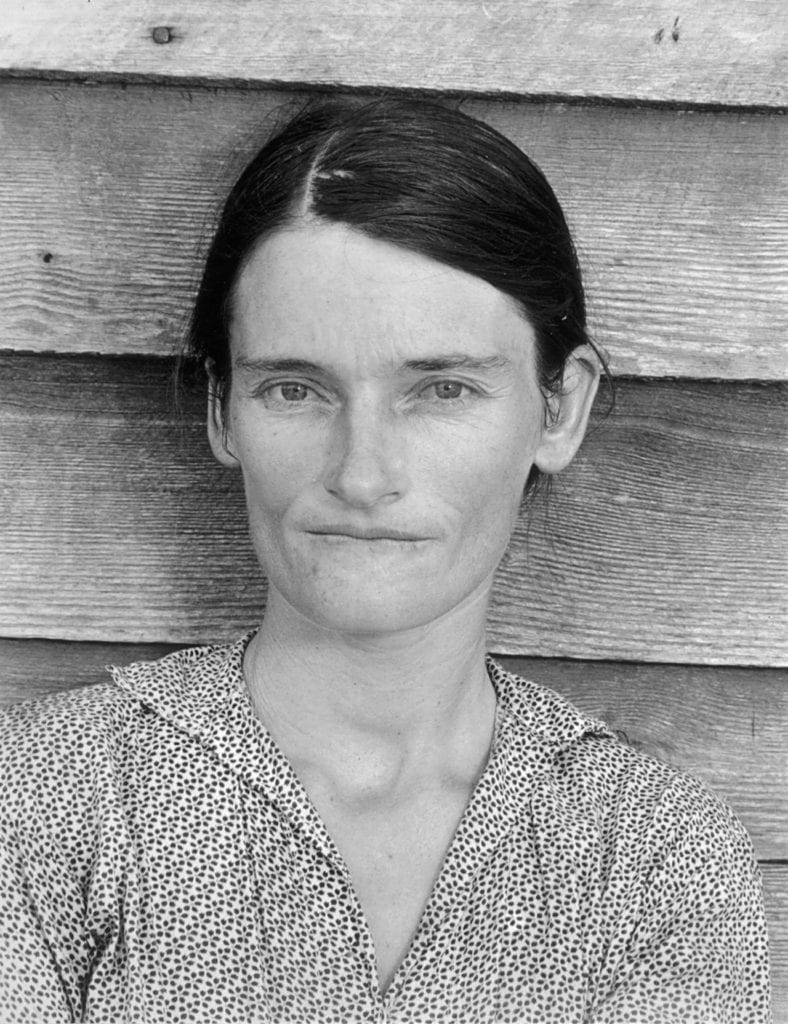

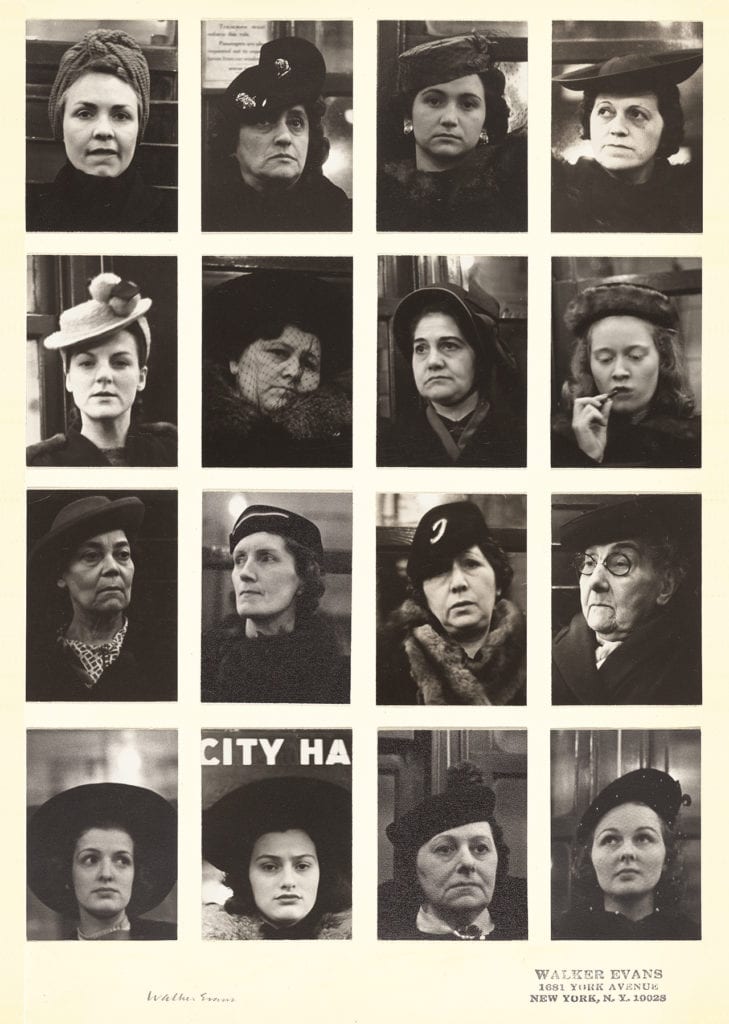

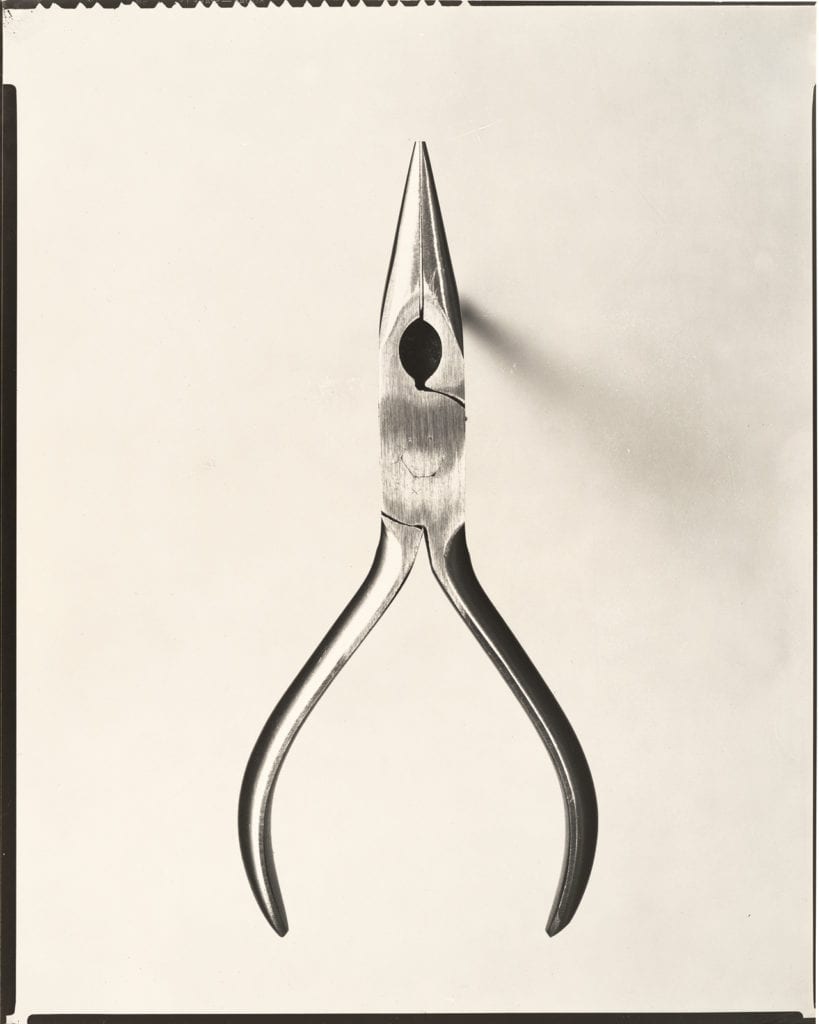

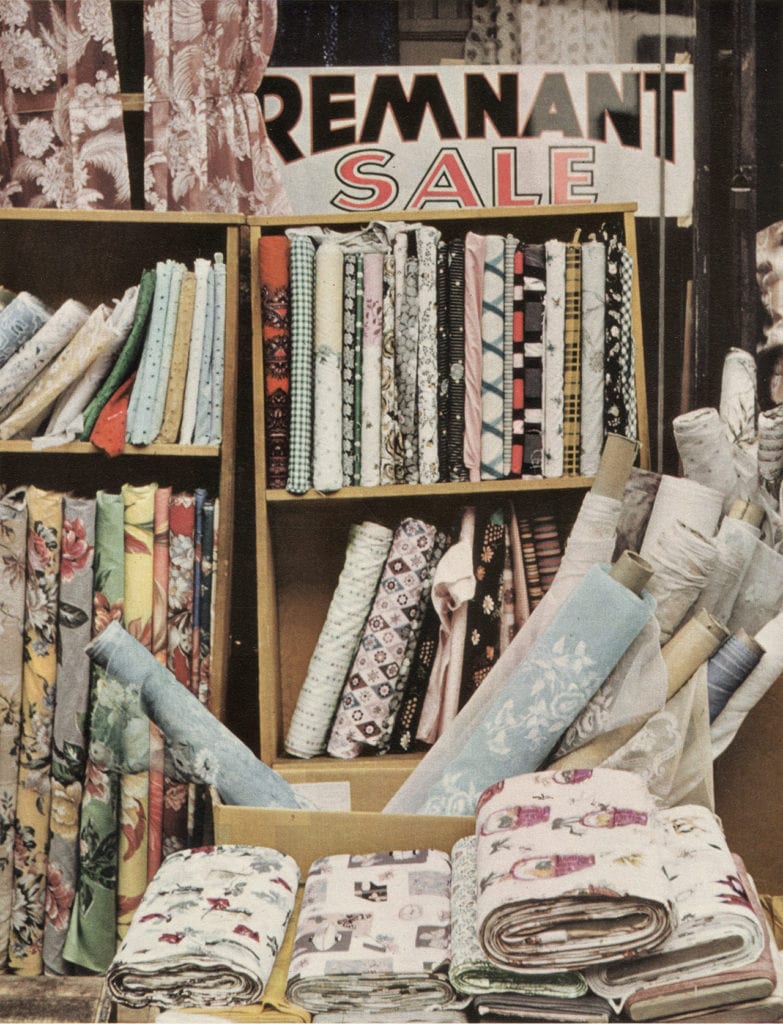

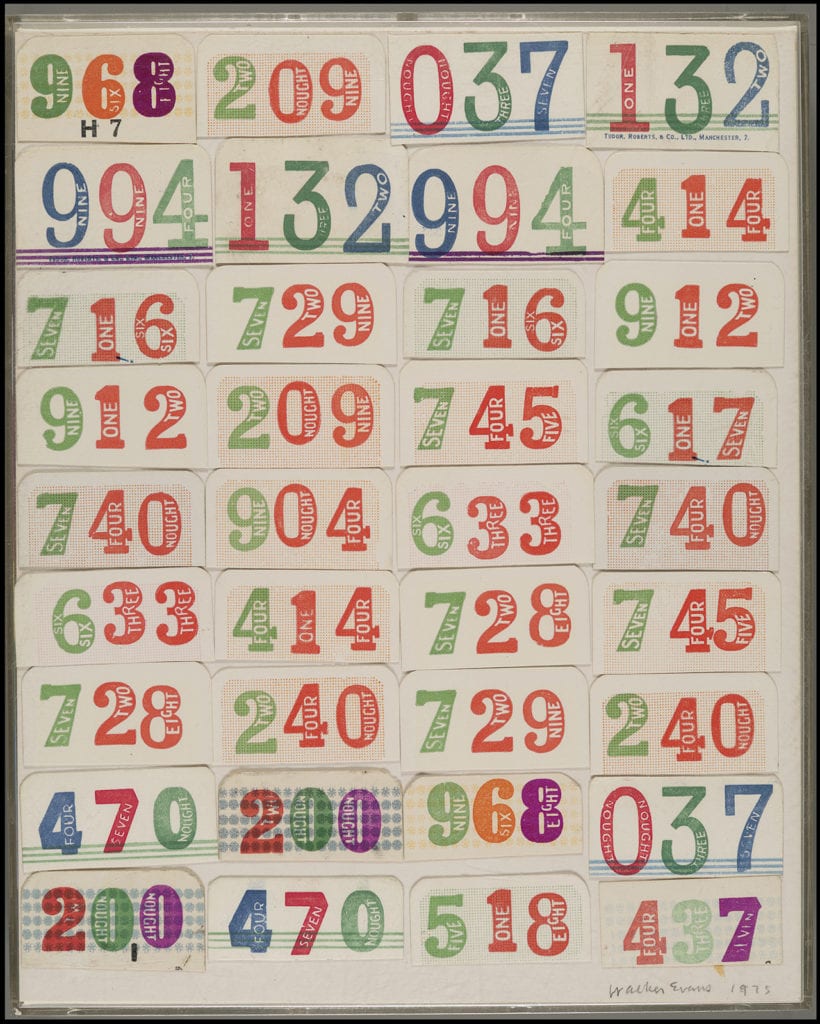

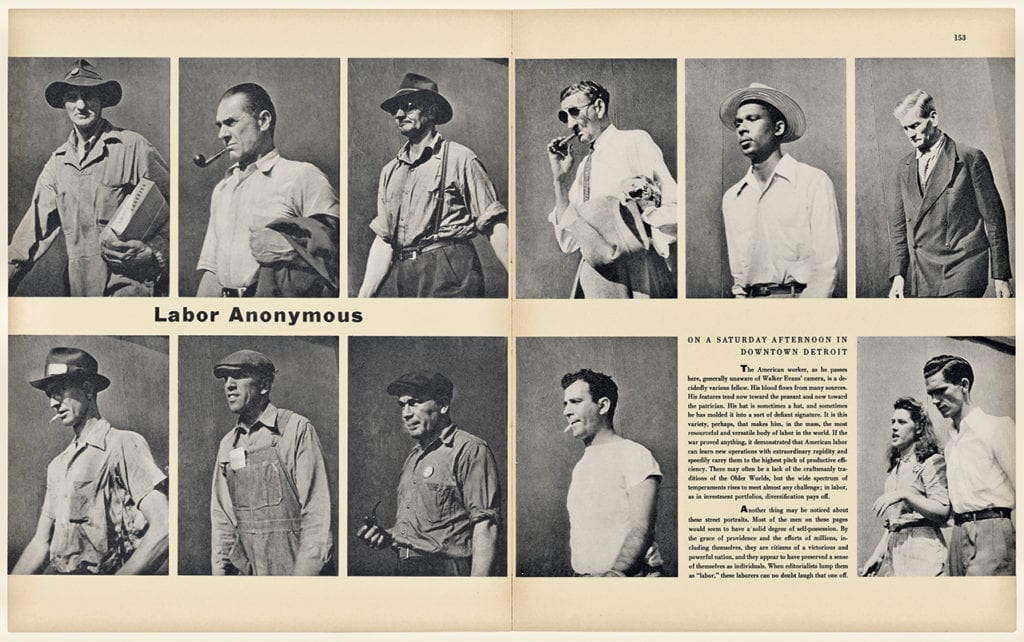

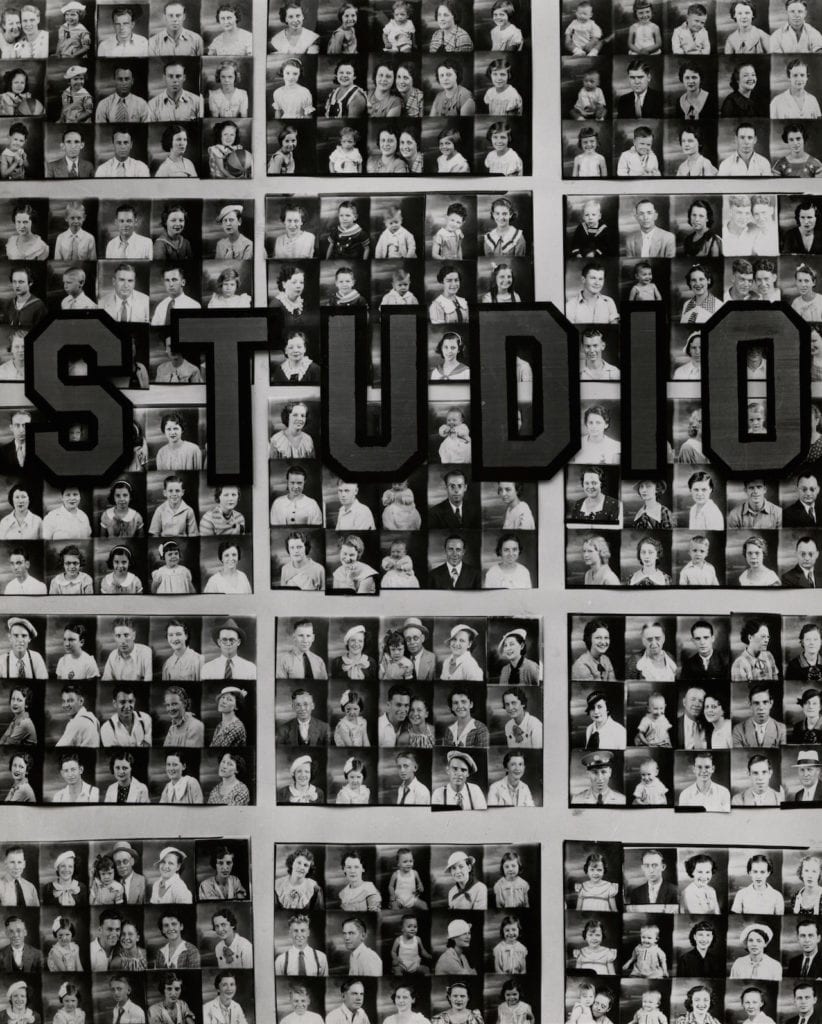

Divided into two parts, the exhibition initially focuses on Evans’ photographs of quotidian sights, including signage, billboards, and shop windows, and also everyday people such as the office workers, labourers and passersby he captured in New York. The second half of the show explores Evans’ use of vernacular methodology, and includes his experiments with architectural and catalogue photography, such as his celebrated still lifes of tools. This section also includes two rooms devoted to Evans’ own collection, which includes bus tickets, lottery tickets, leaflets, roadsigns and postcards – lots and lots of postcards.

“Evans was fascinated with postcards – he started to collected them at the age of 12 and at the end of his life, aged 75, had more than 10,000,” says Chéroux. “In the 1930s he also tried to sell a few photographs as postcards, and he even exhibited them at MOMA.”

“Consider how Henri Cartier-Bresson worked with magazines – he’d shoot, give the images to Magnum, and Magnum would distribute them. For Evans it was not like that at all. He would take the photograph, choose the photography magazine, create the layout he preferred, also adding the title. He was controlling everything, completely unlike to most other photographers at that time. For that reason I consider his work for the magazines as important as his work for books and exhibitions.”

Chéroux joined SFMOMA earlier this year from the Musée National d’Art Moderne of the Centre Pompidou, Paris, which organised this show, and previously showed it this year. Chéroux knows Cartier-Bresson’s work well having curated a major retrospective of his work at the Pompidou in 2014; he’s also known for an exhibition of vernacular photography called Shoot!, which was staged at the Rencontres d’Arles in 2010. He has, as he says, “been researching the idea of the vernacular for a long time”.

“But when I dug into his archive I realised that, though a lot of his friends were leftist, he himself was not political. He had a much more aesthetic, literary interest in the aesthetic, which is way he was also so interested in [the writers] Baudelaire and Flaubert.”

As Chéroux points out though, an exhibition of this size presents an opportunity to rethink an icon, and he credits David Campany and Jeff L Rosenheim with expanding our understanding of Evans through their respective work on his interest in magazines and postcards. “The exhibition opening at SFMOMA is a kind of update on Evans, including all this new research by others,” says Chéroux, adding that both contributed essays to the catalogue.

“It’s important to, every two or three years, have a big exhibition [in the gallery] which makes a big statement about an artist,” he continues. “It’s great to be able to show the whole range of an artist’s career, all the different aspects of their projection and everything that they tried to do, and evaluate and re-evaluate their work.

“We’ve tried to show the whole range of Evans’ work,” Chéroux concludes. “And that’s something you can’t do in 500 square metres.”

Walker Evans is on show at SFMOMA until 04 February 2018, the catalogue is published by Centre Pompidou and Delmonico Books/Prestel. www.sfmoma.org Read BJP’s Any Answers interview with Clement Cheroux here https://www.1854.photography/2017/02/clement-cheroux/