For the past seven years Nicola Lo Calzo has worked tirelessly on CHAM, a project exploring the enduring impact of colonialism and slavery on the African diaspora. In capturing different manifestations of these lingering memories of exploitation, and the fight against it, the Paris-based Italian has spent time in Benin, Togo, Ghana and Senegal (Tchamba), Louisiana and Mississippi (Casta), Haiti (Ayiti), Guadeloupe (Mas) and Suriname and French Guiana (Obia).

Most recently he made four trips to Cuba to examine Afro-Cuban societies and communities which were previously ostracised and marginalised but now operate – mostly – freely. The resulting book, Regla, includes striking documentary photographs and portraits, images of iconography and archival objects, and insightful commentary.

Examining the cultural, religious, and ceremonial practices passed down through generations of African descendants in Cuba, Lo Calzo highlights the variety of identities within the country, and the ways in which they complement one another. Cohabiting “within a personal culture of exchange”, he says, they “borrow each other’s visions, customs and narratives”. He points to the “precarious balancing act” between the familiar Cuba, largely defined by the communist revolution and the society born out of it, and the diverse communities that actually make up the country.

Spending time among the Abakuá all-male secret society, Freemasons, the Cabildos de Nación Africana black brotherhoods, the carnival comparsas, three Afro-Cuban religious communities, and the contemporary Afro-Cuban raperos of underground hip-hop, this work required intense planning and research, he says, and a different approach to CHAM‘s previous chapters.

“It’s complicated to work in Cuba,” he explains. “If you want to go beyond street photography and actually explore the lives of the people you meet it takes a long time, because you have this filter of the revolution and its ideology. It’s difficult to break the wall between an outsider like me and the Cuban people. There’s a kind of apprehension.”

Aberisún íreme moves through the crowd gathered in excitement of the members. Muñongo Efó lodge, Regla. © Nicola Lo Calzo – L’agence à Paris. A plante, by which the Abakuá mean a “religious activity” or ritual of drumming, dancing, and chanting, is a very important time of celebration for the entire Abakuá community. It creates a network of connections between all the “powers”. Those from the oldest to the youngest, and followers of other “powers” as well, move in droves to attend the ceremonies. Some arrive at the place of the activity at the night, while others arrive during the day.

On previous trips for CHAM he worked with the support of local artistic institutions, but in Cuba he decided to go it alone – wary of being put under pressure to take a particular political stance. “The only way for me to work on the Afro-Cuban legacy, and research the freedom and the connections between all these communities, was to work alone and discretely,” he says.

Aberisún íreme moves through the crowd gathered in excitement of the members. Muñongo Efó lodge, Regla. © Nicola Lo Calzo – L’agence à Paris. A plante, by which the Abakuá mean a “religious activity” or ritual of drumming, dancing, and chanting, is a very important time of celebration for the entire Abakuá community. It creates a network of connections between all the “powers”. Those from the oldest to the youngest, and followers of other “powers” as well, move in droves to attend the ceremonies. Some arrive at the place of the activity at the night, while others arrive during the day.

On previous trips for CHAM he worked with the support of local artistic institutions, but in Cuba he decided to go it alone – wary of being put under pressure to take a particular political stance. “The only way for me to work on the Afro-Cuban legacy, and research the freedom and the connections between all these communities, was to work alone and discretely,” he says.

By way of an example he references the Abakuá, a secretive society which formed in 1836 in the port of Regla. Originally founded by slaves of south eastern Nigerian ethnicity, it was ostracised into secrecy until a decade ago, but has since become a popular group for young men, welcoming both African descendants and people with other heritage. Even so its followers remain reticent about strangers, so getting permission to photograph their ceremonies was enlightening but challenging.

“There had to be trust,” Lo Calzo explains. “I presented myself as a photographer and showed them the work I had done in my previous journeys. When you work on post-colonial topics like this it’s very important to be aware of your own position and approach, and the complexity of the reality you are working with.”

Lo Calzo wanted to capture a wide variety of groups and societies, determined to show practices in Cuba that are rarely seen outside the country, but the access he was granted varied. He found it relatively easy to photograph members of the Santería religion, for example, given its mainstream status, but could only get a small selection of photographs of the Cuban Freemasons, who run important schemes in food distribution, community service, and mutual aid with a “negotiated freedom” from the state.

When granted access, Lo Calzo took as many portraits as possible, keen to use the people he met as the “pillars of the story” he was trying to tell. “Behind each portrait there is an interview,” he explains. “And these are very important stories for me to tell because most of the images that exist of Cuba are street photography. I respect that but, at the same time, it gives a kind of stereotypical image of the country. I want to be far from stereotype, from the Dolce Vita. To me that is the opposite of reality.”

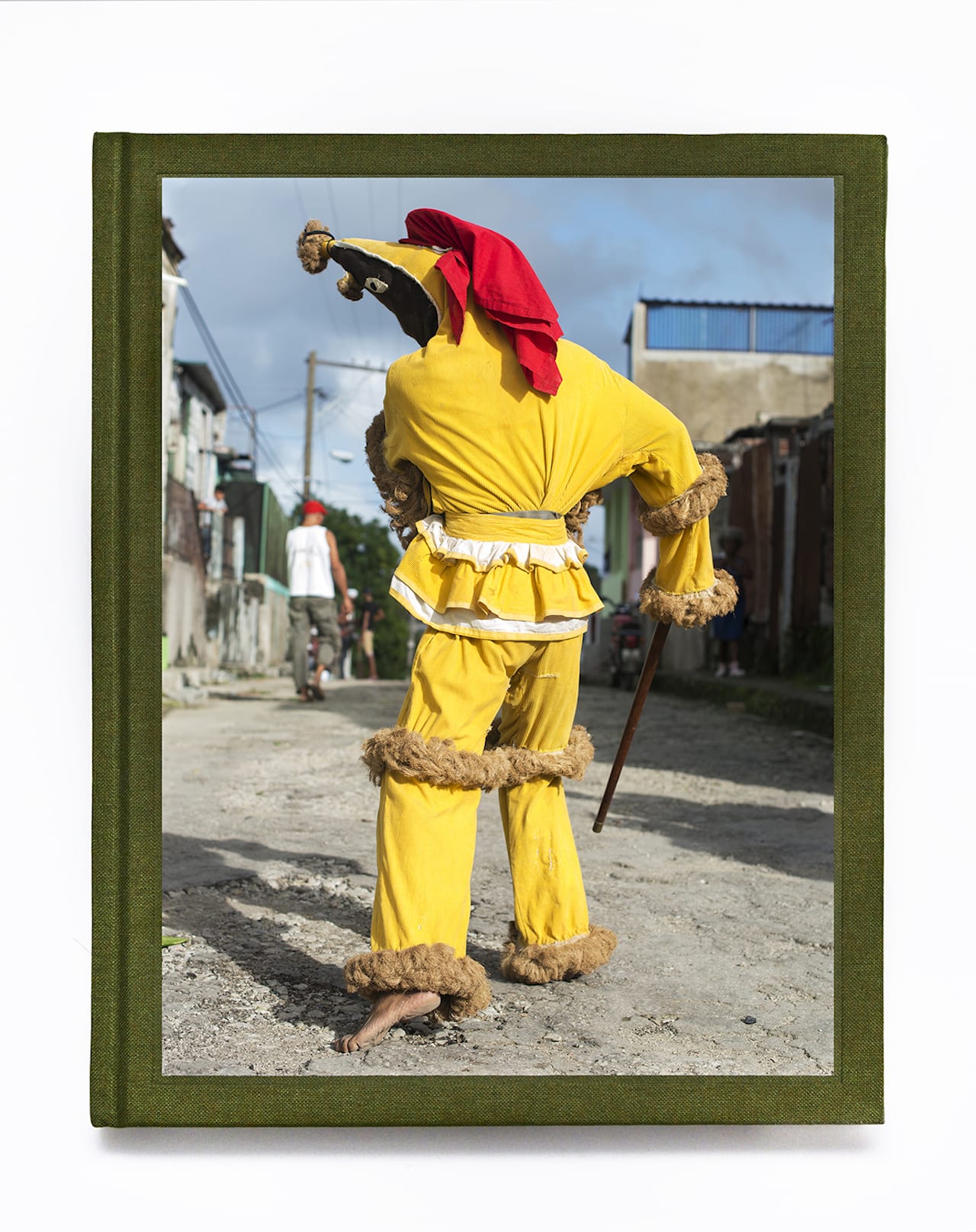

Lo Calzo’s photographs show ceremonies and streets, individuals and groups of all ages, and could not be further from the “revolutionary” cliches he speaks of. There are photographs of the young men and women of the hip-hop movement such as La Reyna and La Real, a ceremonial Abakuá masked dancer (íreme), and many more besides. He believes that these societies and cultural movements, whether they’re guided by rap or religion, allow Cubans a sense of individual expression and identity.

La Reyna and La Real, Centro-Havana, Havana. “We are La Reyna and La Real. There are not many women rappers in Cuba, we are among about fifteen of them. We wish to talk to all women, to all Cuban women, without distinction. We identify primarily as Cuban. That said, our discourse is very attached to the history of Cuba, including the black experience. Discrimination and racism are a legacy…We address women’s issues, the status of women and black women in particular, their place in Cuban society, and racism. Everyone here is mixed, but despite this there is always fear. This is not a state-sponsored racism. It is rather a popular racism inherited from colonialism. You see it in what people say, for instance a statement like, ‘Him, he is not like all the other blacks, etc.’ The colour of one’s skin is fundamental for access to the workplace: the lighter one’s skin, the more opportunities there are. The standard for beauty here is the mulatta, another racial category developed during colonisation. There are not many black role models or black women heroines, because the heroes of Cuban history are never presented from this perspective. The heroes of the national narrative don’t have colour, and are admired for their service to the national unity.” – La Reyna. © Nicola Lo Calzo – L’agence à Paris

“They give to Cubans the opportunity to express themselves as individuals, far from the state power rhetoric,” he says. “You see there is no symbol of revolution in their ceremonies.”

La Reyna and La Real, Centro-Havana, Havana. “We are La Reyna and La Real. There are not many women rappers in Cuba, we are among about fifteen of them. We wish to talk to all women, to all Cuban women, without distinction. We identify primarily as Cuban. That said, our discourse is very attached to the history of Cuba, including the black experience. Discrimination and racism are a legacy…We address women’s issues, the status of women and black women in particular, their place in Cuban society, and racism. Everyone here is mixed, but despite this there is always fear. This is not a state-sponsored racism. It is rather a popular racism inherited from colonialism. You see it in what people say, for instance a statement like, ‘Him, he is not like all the other blacks, etc.’ The colour of one’s skin is fundamental for access to the workplace: the lighter one’s skin, the more opportunities there are. The standard for beauty here is the mulatta, another racial category developed during colonisation. There are not many black role models or black women heroines, because the heroes of Cuban history are never presented from this perspective. The heroes of the national narrative don’t have colour, and are admired for their service to the national unity.” – La Reyna. © Nicola Lo Calzo – L’agence à Paris

“They give to Cubans the opportunity to express themselves as individuals, far from the state power rhetoric,” he says. “You see there is no symbol of revolution in their ceremonies.”

What he finds interesting is the way these societies blend with one another, solidifying a broad Afro-Cuban legacy in these smaller pockets of society. “There’s a crossover of the cultures,” he says. “In Europe the crossover of religion and rap, for example, would be seen as contradictory but in Cuba not at all. You can be a Santero, an Abakuá follower and a rapper at once.”

With more chapters planned for Sicily, Columbia, Brazil and Angola, the anthology Lo Calzo is assembling is of mammoth proportions, but he feels it’s acutely relevant today. He points to the work of French philosopher Edouard Glissant, who spoke of the need for global communities to “remember together” if “we want to share the beauty of the world, if we want to show solidarity with its suffering”.

“We remain with little knowledge about [the descendant African] legacies in the Atlantic World, but I deeply believe that we can not grasp the complexity of the present in which we live without an understanding of them,” says Lo Calzo. “I hope this project can show just how fragile they are but how important they are to preserve.”

“When we think of memory we think of it as being in the past,” he concludes. “But in my practice I’m seeing memory that is still active today”

Regla is published by Kehrer Verlag, priced €35 https://www.kehrerverlag.com/en/nicola-lo-calzo-regla https://www.nicolalocalzo.com/site/

Kehrer Verlag will be at Photo London from 17-20 May https://photolondon.org/exhibitors/2018-2/kehrer-verlag/

Ireme Aberisun during an Abakuá ceremony in the temple courtyard, Erume Efó lodge founded in 1874, Guanabacoa. © Nicola Lo Calzo – L’agence à Paris. Ireme’s attributes have been constants of the Abakuá liturgy from the beginning: pointed cap, a circular hat, a cowbell belt at the waist, a stick in hand (iton), clothing with burlap decorations.

Ireme Aberisun during an Abakuá ceremony in the temple courtyard, Erume Efó lodge founded in 1874, Guanabacoa. © Nicola Lo Calzo – L’agence à Paris. Ireme’s attributes have been constants of the Abakuá liturgy from the beginning: pointed cap, a circular hat, a cowbell belt at the waist, a stick in hand (iton), clothing with burlap decorations.

A dove attached to the entrance of the temple of the Erume Efó lodge founded in 1874. Guanabacoa. Each ceremony includes animal sacrifices (a sheep, roosters, doves) and consumption of ritual food and drink. For that, “Each member contributes 5 pesos per month, the state is there to check, but it is not involved in the activity and does not help us. One plante, by which the Abakuá mean a “religious activity” or ritual of drumming, dancing, and chanting, costs between 3,000 and 5,000 Cuban pesos” – President of the Abakuá office of Regla. © Nicola Lo Calzo – L’agence à Paris

A dove attached to the entrance of the temple of the Erume Efó lodge founded in 1874. Guanabacoa. Each ceremony includes animal sacrifices (a sheep, roosters, doves) and consumption of ritual food and drink. For that, “Each member contributes 5 pesos per month, the state is there to check, but it is not involved in the activity and does not help us. One plante, by which the Abakuá mean a “religious activity” or ritual of drumming, dancing, and chanting, costs between 3,000 and 5,000 Cuban pesos” – President of the Abakuá office of Regla. © Nicola Lo Calzo – L’agence à Paris

Release of Ireme for a ceremony, on the patio of Muñongo Efó lodge, Regla. The Ireme, pejoratively called diablito, is surely the most picturesque and representative character of the Abakuá religion. It is a supernatural being who comes to earth to intervene in Abakuá ceremonies, and ensure the accuracy of what is done. There is an Ireme for each different time of the ceremony. The Ireme needs a character to guide him throughout the performance, called the Morua, who speaks and sings using elements of the Efik language. Sociologist Tato Quiñones defines the Ireme as “beings from beyond the grave … that see and hear but do not speak and express themselves through their gestures and choreography.” © Nicola Lo Calzo – L’agence à Paris

Release of Ireme for a ceremony, on the patio of Muñongo Efó lodge, Regla. The Ireme, pejoratively called diablito, is surely the most picturesque and representative character of the Abakuá religion. It is a supernatural being who comes to earth to intervene in Abakuá ceremonies, and ensure the accuracy of what is done. There is an Ireme for each different time of the ceremony. The Ireme needs a character to guide him throughout the performance, called the Morua, who speaks and sings using elements of the Efik language. Sociologist Tato Quiñones defines the Ireme as “beings from beyond the grave … that see and hear but do not speak and express themselves through their gestures and choreography.” © Nicola Lo Calzo – L’agence à Paris

A group of soldiers in mambi garb (former anti-colonial combatants in the war of independence), arrive at fort Castillo del Morro for the daily Cañonazo ceremony, Santiago. This ceremony was practiced during colonial times just before the closure of the defensive walls of the Spanish colonial cities. Today, though no longer retaining its original signification, it is still practiced by real soldiers, dressed in mambises, the anti-Spanish Cuban guerilleros during the war of independence. The symbol of anti-Spanish resistance is thus integrated into the national discourse. © Nicola Lo Calzo – L’agence à Paris

A group of soldiers in mambi garb (former anti-colonial combatants in the war of independence), arrive at fort Castillo del Morro for the daily Cañonazo ceremony, Santiago. This ceremony was practiced during colonial times just before the closure of the defensive walls of the Spanish colonial cities. Today, though no longer retaining its original signification, it is still practiced by real soldiers, dressed in mambises, the anti-Spanish Cuban guerilleros during the war of independence. The symbol of anti-Spanish resistance is thus integrated into the national discourse. © Nicola Lo Calzo – L’agence à Paris

Eba Emerida Augustin and Sergio Ramo, Queen and King of the Carabalí Olugu founded as the Cabildo de Nación Africana in 1783. Santiago Carnival. Originally, the Cabildo de Nación Africana was a gathering of black African freed slaves, belonging to the same ethnic group, whose role was to provide mutual aid, support in times of sickness or death, and the transmission of their traditions. The cabildos de nación in Cuba will always have two guardians, the State and the Church. © Nicola Lo Calzo – L’agence à Paris

Eba Emerida Augustin and Sergio Ramo, Queen and King of the Carabalí Olugu founded as the Cabildo de Nación Africana in 1783. Santiago Carnival. Originally, the Cabildo de Nación Africana was a gathering of black African freed slaves, belonging to the same ethnic group, whose role was to provide mutual aid, support in times of sickness or death, and the transmission of their traditions. The cabildos de nación in Cuba will always have two guardians, the State and the Church. © Nicola Lo Calzo – L’agence à Paris

“The Lamento Cimarron trio is a government project run by the Miguelito Cuni Music Center in the Pinar del Rio province. It was created 17 years ago, not by current members but by others, one of whom lives in England and the other in the Canary Islands. Our purpose is to reconstruct the lives of maroon slaves in this cave for a public that is, for the most part, comprised of tourists. Many tourists are interested and ask questions about our ancestors and their suffering during the slavery era. Others think we do this just for culture and fun. We have explained to them that it’s also a way of honoring them. They are stunned at the treatment suffered by maroons who wanted to be free.” – Oneida. © Nicola Lo Calzo – L’agence à Paris

“The Lamento Cimarron trio is a government project run by the Miguelito Cuni Music Center in the Pinar del Rio province. It was created 17 years ago, not by current members but by others, one of whom lives in England and the other in the Canary Islands. Our purpose is to reconstruct the lives of maroon slaves in this cave for a public that is, for the most part, comprised of tourists. Many tourists are interested and ask questions about our ancestors and their suffering during the slavery era. Others think we do this just for culture and fun. We have explained to them that it’s also a way of honoring them. They are stunned at the treatment suffered by maroons who wanted to be free.” – Oneida. © Nicola Lo Calzo – L’agence à Paris

REGLA cover © Nicola Lo Calzo – L’agence à Paris

REGLA cover © Nicola Lo Calzo – L’agence à Paris