The circus was over and Gary, Richard and I ‘went exploring’; we were about nine years old. Our objective was the cages of the big cats, but we first encountered one of the ensemble, sitting on the steps of a caravan, smoking a cigarette. Gary, the most forward of us, said to him: ‘That was brilliant! The lions were brilliant. You’re a clown! What’s your name?” (Gary is intuitive, though the pancake make-up may have provided a clue).

The clown, no doubt fatigued by his efforts to entertain us, withdrew his cigarette, exhaled slowly and roared: ‘Shag off outta here, yiz feckin’ little bowsies!’

My memory of the precise terminology may be inexact, but the message, and my recollection of it, is clear – we were not welcome because, uninvited, we has crossed the invisible divide between the front-of-house fantasy of the Big Top, and the reality behind the facade.

For some 26 years Peter Lavery has been intermittently crossing this divide, far from uninvited but welcomed, with a warmth that has increased with the passing years, by a group traditionally known for its insularity. The result is an exhibition, Circus Work, at the Royal Photographic Society in Bath and a supporting book of the same title.

“I now meet up with these people when I go back to the circus. I’ve picked up on a lot of these pictures [in 1996] to finish the sequence, because I didn’t want it to tail off, so last year I took more pictures than I did since the mid-70s.

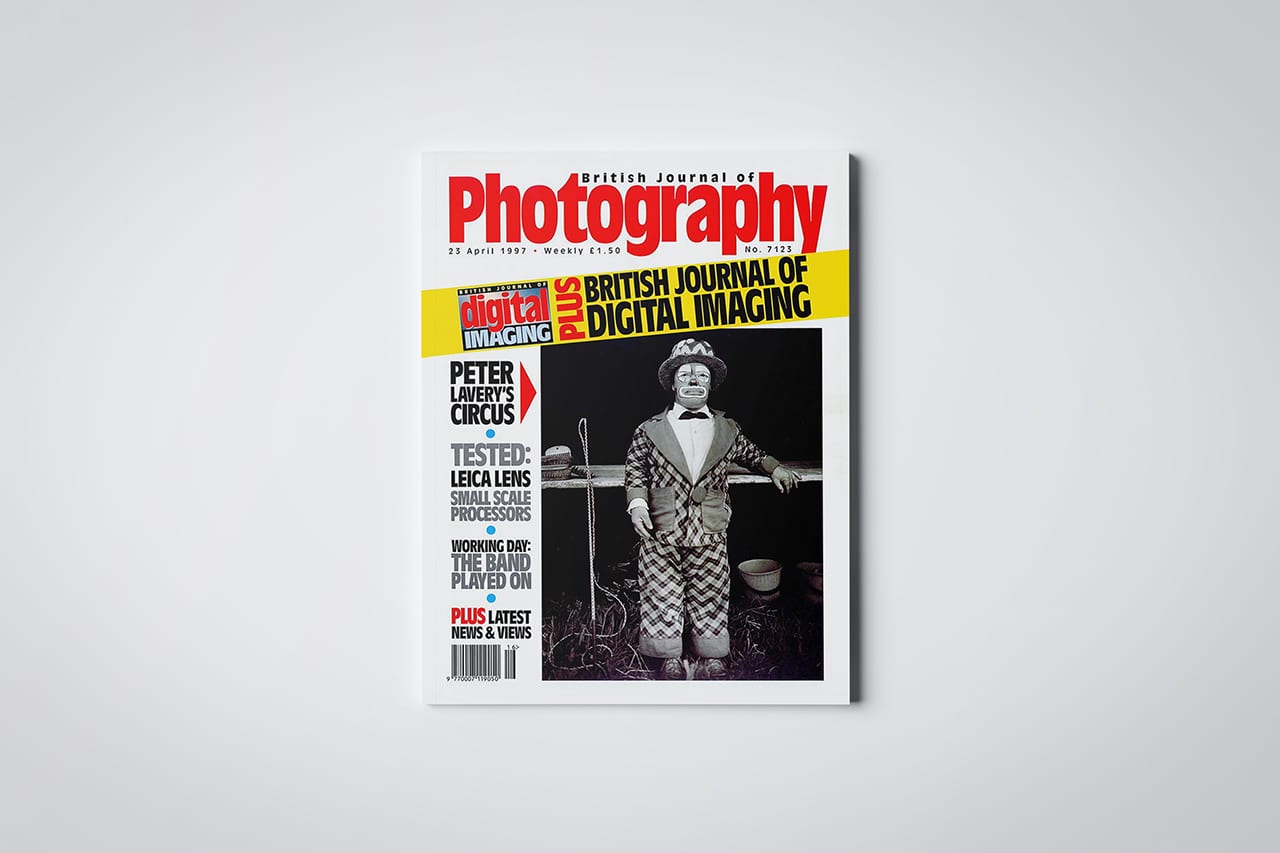

“For example this picture of Peter Jolly Junior; when I photographed his father, also Peter Jolly, back in the 70s Peter Jolly Junior wasn’t even born. I went back in November, and I hadn’t seen Peter Jolly in 20 years, but he remembered me and I remembered him.”

The Jollys are something of a curiosity; they are pictured here when their mini-circus visited Fishguard in 1974. Between them, Carol and Peter Jolly did everything… pitching the tent, taking the money, performing the acts, “even changing the records”, recalls Lavery. These days labour is more equally divided, now that their four children are on board.

“I started Circus Work at college [Lavery has an MA in Photography from the Royal College of Art]. I was visiting home in Wakefield, and I took in a a performance of the Winships Minicircus in the Queen’s Hall in Leeds. That’s where it started.”

Lavery then undertook an odyssey, following the many circuses on their meandering itineraries around the UK and Ireland. Transport and sustenance seem to have been left to chance and accommodation might easily be bare earth under a caravan. Typically he would stay with one outfit for just a day and a night before moving on to the next. Such a vagabond life might at first glance seem romantic, but it must, in fact have been uncomfortable in the extreme. However, such evident doggedness, such a willingness to share the everyday discomforts of the travelling life, may be a clue as to why Lavery and his camera were accepted without demur.

The absence of colour at first seems perverse, for the attraction of the circus is perhaps best described in terms of colour; from the scarlet of the ringmaster’s coat, through the harlequin motley of the clowns, to the sequinned emeralds, cerises, yolk-yellows and cerulean-blues of the acrobats’ outfits. But Lavery stresses that this is not a photo essay on the circus per se, but instead a series of portraits of the artistes, and black-and-white is eminently well suited to the job of recording the human face. In any case the wondrous lustre of the platinum print, so beloved of Lavery and examples of which comprise the greater part of the exhibition, may be said to have its own colour.

Informing Lavery’s images is his concern to portray the reality behind the fantasy, the human face behind the theatrical make-up. Thus we are presented with a procession of contortionists, fire-eaters, animal trainers and knife throwers in all their finery, gently juxtaposed with the ordinariness of circus life out side of the Big Top. So we see them against a variety of quirky backdrops; a clown on a seaside pier, a ring master silhouetted against a thatched cottage, a balancer doing a handstand in an Irish field.

And life isn’t easy away from the performance. It is often damp, cramped, muddy and sometimes shabby, with peeling paint, crumbling masonry and stained canvas. But there is nothing ironic or knowing about Lavery’s work, no sense of “Look at these sad specimens”. Rather a sense of mutual respect, and sometimes mutual affection, is evident.

There is a story running through Lavery’s pictures, an inevitable one – he charts the progress of a dozen families down the decades and their relationships with each other. For circus is a generation game and certain names run through the story like a thread – Baba Fossett, Elaine Courtney, Sophie Chipperfied, everybody in the circus world, it seems, is related to everybody else.

Not all performers stay the pace, however. Lavery notes those who have retired from the circus life and their current occupations – florist, antique furniture restorer, tent hire business, “married to a soldier, living in Ireland”. And then there are that have simply passed on during the years since Lavery began picturing the circus.

It is the clowns who seem to suffer most in this regard – Frankie Veronica Bailey (whom Lavery photographed on his inaugural visit to the Queen’s Hall, Leeds), Robert ‘Bobo’ Fossett, Jimmy Buchanon. Also gone is the World’s Smallest Strongman, Tony Carrol, and perhaps most tragically, Ruslan Darbekov, a Ukrainian who visited with the Moscow State Circus in 1988. He was killed by a rival faction in the aftermath of the Russian political upheaval.

As the century closes, the circus world finds itself beleaguered. Large exotic animals are an increasingly rare sight – they are expensive to keep and many view their involvement as politically incorrect. Escalating costs and ever-increasing competition from alternative sources of entertainment have pared down the margins. But Lavery’s pictures offer hope, for these people are nothing if not survivors, and well used to facing adversity.

In his insightful foreword to Circus Work, Bruce Bernard expresses the hope that viewing the book may tempt us back to the circus. I don’t know if Gary, an accountant now, and Richard, a solicitor, share my yearning to go back to that circus in that field, but in any case it is a futile desire. Because you can’t turn the clock back and because a supermarket stands on the site today.

Circus Work by Peter Lavery – which now covers 50 years of photography – is on show at Harley Gallery, Welbeck, Nottinghamshire from 03 February-15 April https://www.harleygallery.co.uk/exhibition/circus-work/