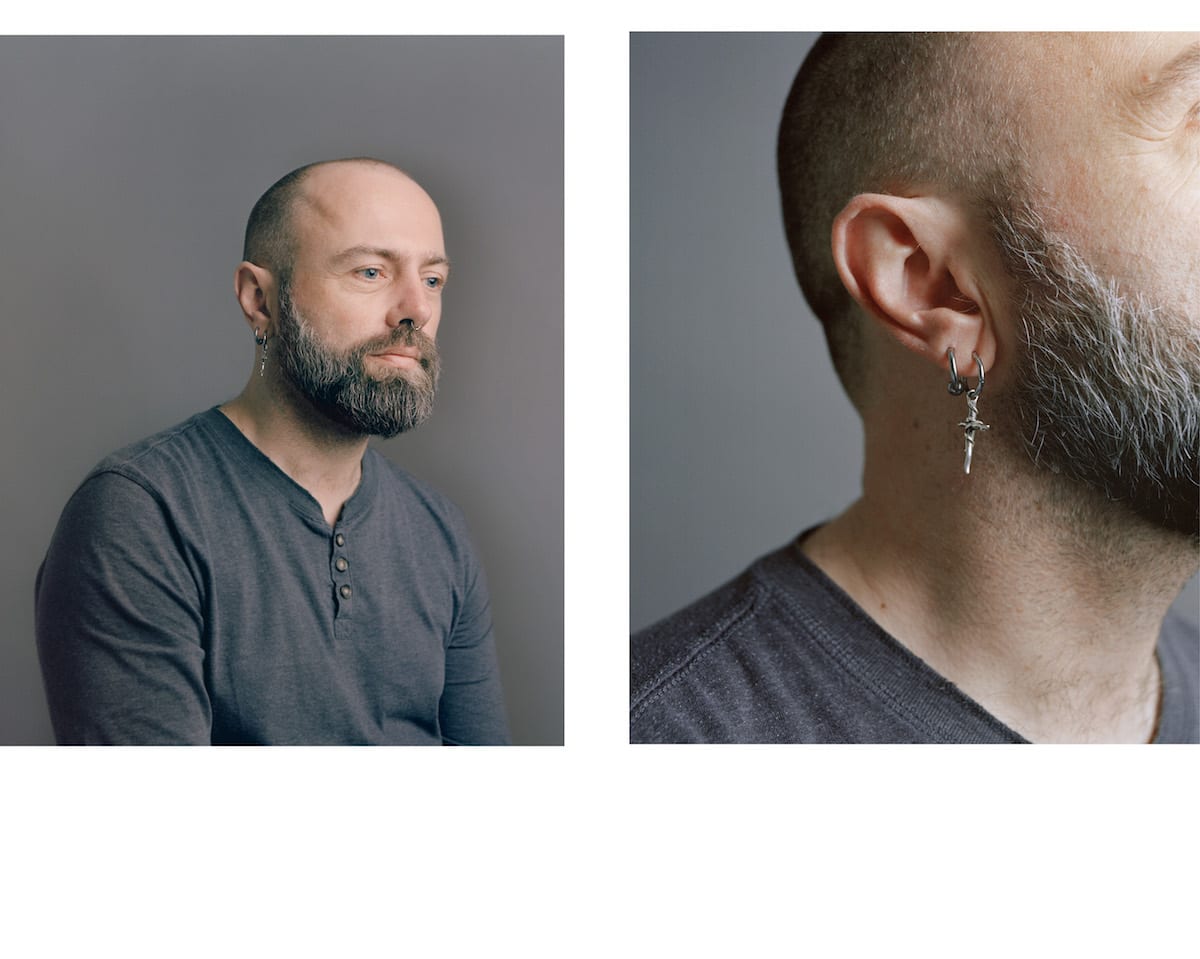

Harry Flook is a Bristol-based writer and photographer, whose photographic work is rooted in his personal experiences. Having left his own religious faith, he embarked on ‘Apostate’, a project photographing those who had done the same, and he stumbled across a vast community of ex-religious individuals while doing so. Making this work then culminated in another project, ‘Beyond What is Written’, set in the heart of ‘bible belt’ America and addressing the subject from a different perspective. Both series explore the concept of community outside religion, for people whose sense of community was once constructed by the religious groups they were a part of.

Harry entered a portrait from ‘Apostate’ into Portrait of Britain 2017, and it was displayed across the country as part of our nationwide exhibition. We spoke to Harry about the value of awkwardness, choosing the perfect subject, and creating a compelling portrait.

How did you create your selected portrait, and what was the story behind it?

This portrait was shot as a test for a project I’m still working on, ‘Apostate’. The image was shot outside using natural light and a reflector against a portable backdrop. I was trying to find a visual style that I could use consistently for the project, and this was one of the images that came together as a standalone portrait.

The portrait was a test for your ongoing series, ‘Apostate’. How has that project developed since your photograph was selected for Portrait of Britain?

‘Apostate’ is about my experience leaving the religious faith I grew up with, explored through conversations with others who had done the same. I found a whole community of ex-religious individuals in the UK from various faiths, many with similar and far more difficult stories than my own. Since this portrait, I have realised that apostasy, as it’s known, is more common than I’d thought. Many people go through it silently. The project led me to shoot another body of work based in Tennessee, a state known as ‘the Heart of the Bible Belt’, where I spent a month photographing the non-religious community who are ostracised from the wider culture. That project is called ‘Beyond What is Written’.

Clive, Ex-Eucharistic Minister, From the series Apostate © Harry Flook

How do you think you have benefited from being selected?

I was selected during my final year at university, and it was the first real affirmation I’d had from the world of contemporary photography, beyond my tutors and friends. So aside from the obvious exposure, to be selected by British Journal of Photography really gave me the confidence to value my work, to knock on the doors of editors, and to get my graduate project published.

How do you choose and work with subjects to achieve your final image?

Choosing subjects really depends on the project I’m shooting. But when making standalone portraits, I’m certainly drawn to people who have striking features or an interesting story to tell.

I often feel slightly awkward shooting people’s portraits, and I sort of invite that feeling to begin with. I won’t direct the subject much initially, I’ll just get them to sit or stand, and take a few frames. Then I’ll begin to direct more heavily, ask the subject to look this way or that, maybe do something different with the light, and shoot slightly more posed frames, so I have a good variety to choose from.

What do you think makes for a compelling portrait?

It’s hard to say what makes a good portrait. I find that once a formula is established, they can become trite and uninteresting. I was recently looking at people on a bus that had stopped at traffic lights. I wanted to stare but I felt awkward as people caught my gaze. It got me thinking about why we find portraits so compelling generally. I think it’s because they allow us a longer glance than social norms allow. Beyond that, it comes down to the way portraits are crafted visually, and the relationship between photographer and subject is always an interesting one; it has a huge influence on the outcome of a portrait.

Do you have any advice for future entrants about selecting a portrait to submit and, more generally, about getting into portrait photography to begin with?

Try to throw out your own attachment to images when submitting, and pay attention to which get the biggest reaction instead. I’m not saying to ignore your own taste completely, but you will be bias toward certain portraits because of your experience taking them, and your knowledge of where they sit in context to other work. When you’re submitting a portrait to be displayed on a billboard without any context other than being a Portrait of Britain, you want something with broader appeal. Social media is a great place to test for it.

When getting into portrait photography to begin with, make sure you shoot lots of portraits and try different approaches. It will help you find your niche. At first, I shot portraits without worrying about the work fitting into a project. I tried different cameras, formats, backdrops, lighting etc. The only way you’ll find your bag of tricks is to shoot lots and get lots of feedback.

Future generations will look to Portrait of Britain 2019 to see the face of the nation in a historic moment. What will it look like? Enter your work today!