Fashion photography, by its very definition, is destined to straddle the realms of art and commerce. This is perhaps never truer than for editorial fashion photographs, which are traditionally made to be consumed in sequence on glossy paper in a magazine before being placed back onto a shelf. They are not, generally, created with a gallery wall in mind. But fashion photography is changing – as Holly Hay and Shonagh Marshall, co-curators of a new three-part project entitled Posturing: Photographing the Body in Fashion, will attest.

In November 2017, the pair held a London exhibition which placed 42 framed photographs and six magazine shoots in a west London space. It called into question both the function of this branch of contemporary image-making and the changing role of the figure in fashion imagery, placing work by Johnny Dufort, Marton Perlaki, Charlie Engman, Brianna Capozzi and others side by side.

The show was followed by a specially commissioned film by artist Coco Capitán, Learning to Transcend the Physical Barrier That Owning a Body Implies, examining the respective practices of a choreographer, an artist and the founder of a traditional film-based darkroom, interrogating physical selfhood in all of its guises. This month, they launch the third part – a book created with Self Publish, Be Happy, in which photographers, stylists, editors and set designers respond to ideas about the body in fashion.

The results are powerful and exhilarating, exploring uncharted territory. But most importantly, Posturing prompts questions: what is this new landscape, in which glamour and opulence have been superseded by humour and absurdity? Why are those girls hiding underneath a dress? Where have all the traditional models gone? “The overarching theme of the exhibition is purely aesthetic,” says Marshall, an independent fashion curator and archivist.

A comprehensive analysis of their subject, rooted in theory and researched in full, was simply too long-term an endeavour given the timeframe, she explains. Instead, the figure is a start-off point: “It’s about the way that the body’s positioned, and how that alters our reading of the clothes.”

The concept was born out of a three-year stint Marshall spent immersed in hairstylist Sam McKnight’s 40-year archive for 2016’s exhibition Hair by Sam McKnight at Somerset House. Emerging from this glamorous world – one dominated by supermodels, couture gowns and extravagant beauty – Marshall was struck by the juxtaposition of such images with contemporary fashion ones, which were, by comparison, surreal, haphazard, humorous and unexpected.

Duly inspired, Marshall turned to her great friend and like mind, Holly Hay, photographic director of Wallpaper* and previously photographic editor at AnOther, who set about collecting 150 photographs by contemporary image- makers which viewed the body in varying lights. Then the pair began a conversation with their chosen photographers.

“That was the most fascinating thing for such contemporary works, to be asking these questions to these people who never ever get asked them,” continues Marshall. And while the idea behind the exhibition began with the body – abstracted, contorted, concealed and made new – the subject quickly became much broader.

Speaking with the people behind the photographs, the pair began with the body as it is captured now. From this, a series of threads emerged which seemed to run throughout the images selected, pinpointing a new shift in fashion photography.

An unconventional approach to styling became a powerful recurring theme, for example – as in photographs created by Charlie Engman with Karen Langley for AnOther magazine spring/summer 2014, in which model Sibyl Buck holds a dress in front of her naked body, her forearms threaded through its armholes; or in a photograph taken by Joyce NG and styled by Rich Aybar for 1 Granary, which sees two young girls beneath a model’s outstretched legs, playing house in the voluminous swathes of her dress.

For many contemporary image-makers, clothes seemed to function as a prop rather than as a disguise. “The clothes are so important,” says Joyce NG. “It’s about making shapes and collaging before the shoot, and getting all the elements together. We want to create new potentials.”

Casting was another key point, says Hay. She and Marshall talked to photographers at length about their processes, and many described casting models on the street, looking not for a stereotypically ‘perfect’ body, but rather for a character. They found that as a result, the subject of a photograph takes part in its creation just as fully as the stylist or make-up artist.

“That was the biggest thing that we learned,” says Hay. “That the character in the image is a collaborator as much as anyone else – and that was really common to all of the photographers we featured.”

Where photographers worked with more traditional types of models, they often spoke about asking them to forget everything they had ever learned about posing for pictures, she continues. “That in turn leads to the photographer becoming a performer too, drawing new movements out of their subject.”

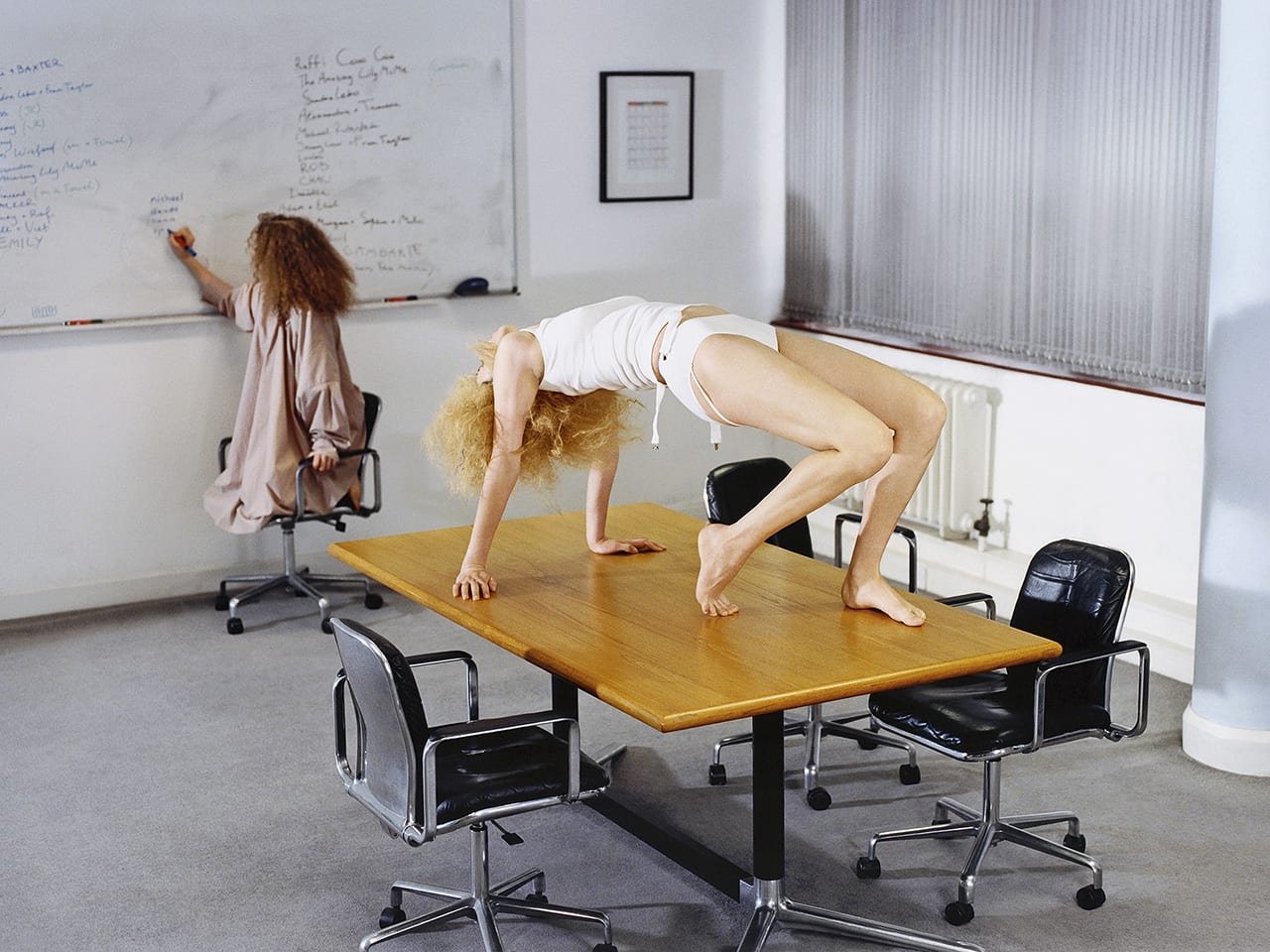

As for location and set design, Hay and Marshall noted a move away from fantastical sets and towards the domestic sphere: Pascal Gambarte shoots a woman in a crab pose on a corporate office desk for Marfa Journal; Blommers/Schumm capture their subject contorted awkwardly on a suburban pavement for The Gentlewoman. “Perhaps it’s a place you recognise as somebody’s home,” says Hay, “or it’s an office, and you’re wondering what the hell they’re doing on a desk in their underwear.”

This transition away from all-out opulence might be a reflection of contemporary consciousness, suggests Marshall. “In the times we live in, when everyone is so engaged and we’re very aware about what’s going on in the world economically, socially and politically, doesn’t a country manor and a tumbling couture gown feel quite out of place? It’s a shift in approach – fashion photography is so representative of its time.”

Most powerful of all, however, was the assertion that fashion provides a means of collaboration; where once fashion photographs were as much a commercial as a creative endeavour, shooting for a magazine now serves as an excuse for dialogue – between the hairstylist, make-up artist, art director and retoucher.

“Although the fashion is important, the image isn’t at service to the garment,” says Hay. “Rather every element of the picture – the hair and make-up, the fashion, the props, the location – is in service to the image. The important thing for everyone, including the magazine, is the image. And that feels like a very big shift in the conversation.”

Working with like-minded collaborators in this way is more than simply a creative shorthand. It also allows creatives in the industry – one infamous for its breakneck pace – to create space and communities within which to learn and grow. Zowie Broach, head of fashion at the Royal College of Art, has seen first-hand what impact coming up in the media’s eye can have on emerging designers and artists, and thus sees collaboration as a welcome opportunity to create dialogue.

“Fashion is such a complete language,” she says. “You’re not just learning colour, you’re learning cut, and material, and make, and silhouette, and photography, and styling, and theatre, and catwalk. That’s a lot. So I think community is a very important thing going forward.

“The fashion industry and fashion education always talk about the designer, but fashion doesn’t exist as one – it’s about teams of people. And you need not just your team, but you need a community and a tribe that will follow you.”

Furthermore, it marks a return to a more traditional way of working – one in which many photographers, stylists, models and collaborators have flourished in the past. “I first met Shonagh and Holly when they came to the RCA to give a talk, and what they were talking about reminded me of the early 1990s – that period of David Sims, Corinne Day and Juergen Teller,” Broach continues.

“That was a really interesting time in fashion photography, before they all became huge; the clothes weren’t important but they were all working together again and again, and building their community, and learning that chemistry with each other. They didn’t become the people that we know overnight – you need to allow that space to grow your language.”

With all parties so invested, contemporary fashion images serve as an enthralling celebration of the fashion they feature. Not seen as it is shown on the catwalk perhaps – here dresses, bags and shoes are subverted, inverted, turned inside out and upside down.

They’re worn by shopkeepers and street-cast strangers in living rooms and on roadsides, and function alone when posted on Instagram just as well as they do in sequence. But the clothes remain front and centre, Hay enthuses – “in a really exciting way.”

Posturing by Holly Hay and Shonagh Marshall is published by Self Publish, Be Happy, priced £25 https://shop.selfpublishbehappy.com/product/posturing hollyhay.co.uk shonaghmarshall.com This article was first published in BJP’s April issue, available via www.thebjpshop.com