Interviewing Nigel Shafran is a circuitous, informal affair. Meeting him at his North London home, I immediately recognise Ruth, his partner and the subject of many of his photographs. I also meet his son Lev, who, though somewhat older, is also still easily discernible from his father’s pictures. The interview takes place in the kitchen familiar from Flowers for ____.

Every now and then a friend calls round or phones, with plans made to throw a boomerang around in the park that afternoon, or play ping pong in the evening. Lev occasionally interjects from the living room with his take on the interview process, or on “nattering on about photography” as he puts it.

“Sorry. Oh my God!” says Shafran, as the phone rings for the second time. “No worries,” I say. “You’re a busy man.” “A busy family man!” he replies. It doesn’t always make for an easy interview, but it feels appropriate for a photographer who focuses on the everyday, the domestic and the personal.

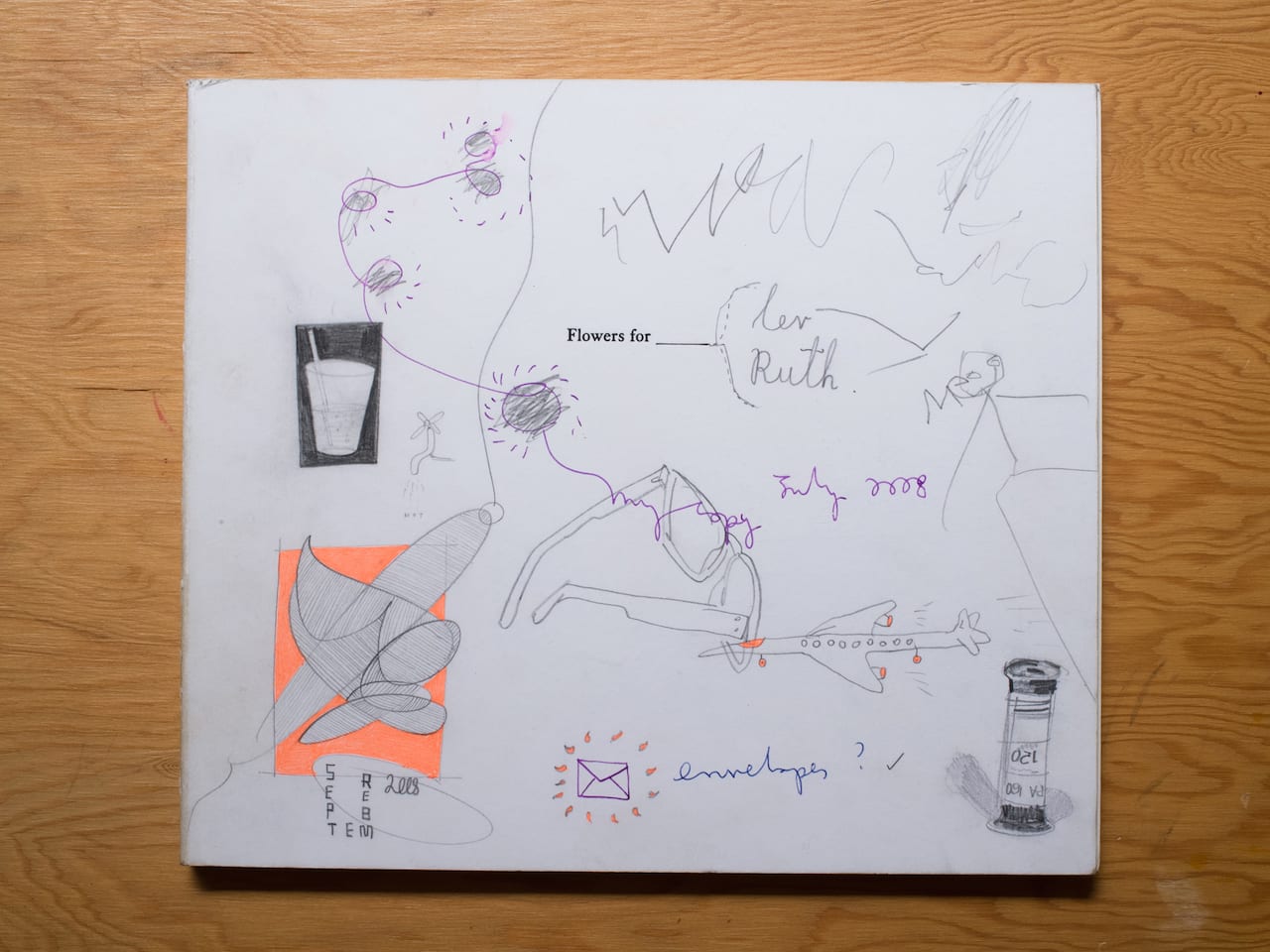

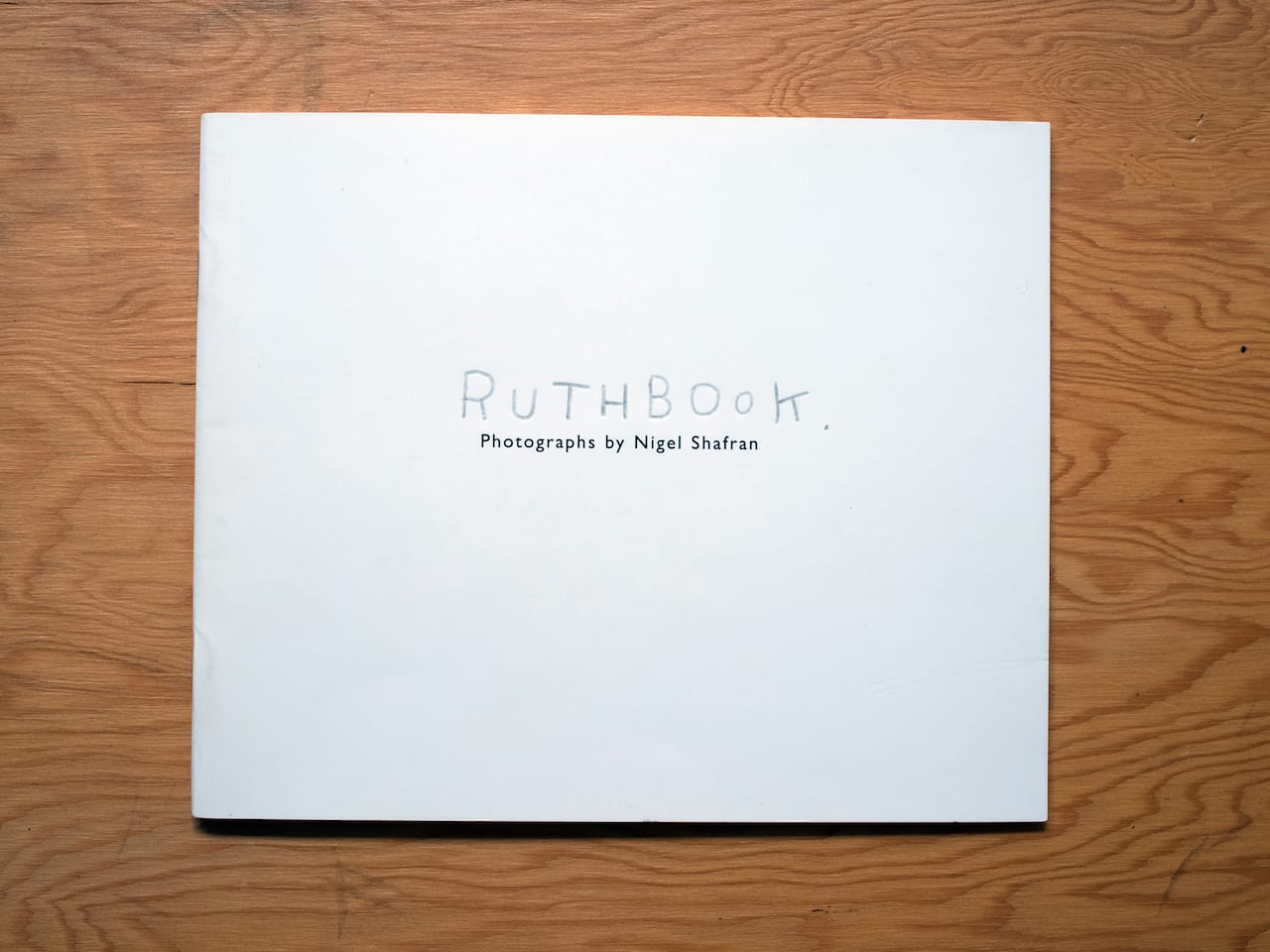

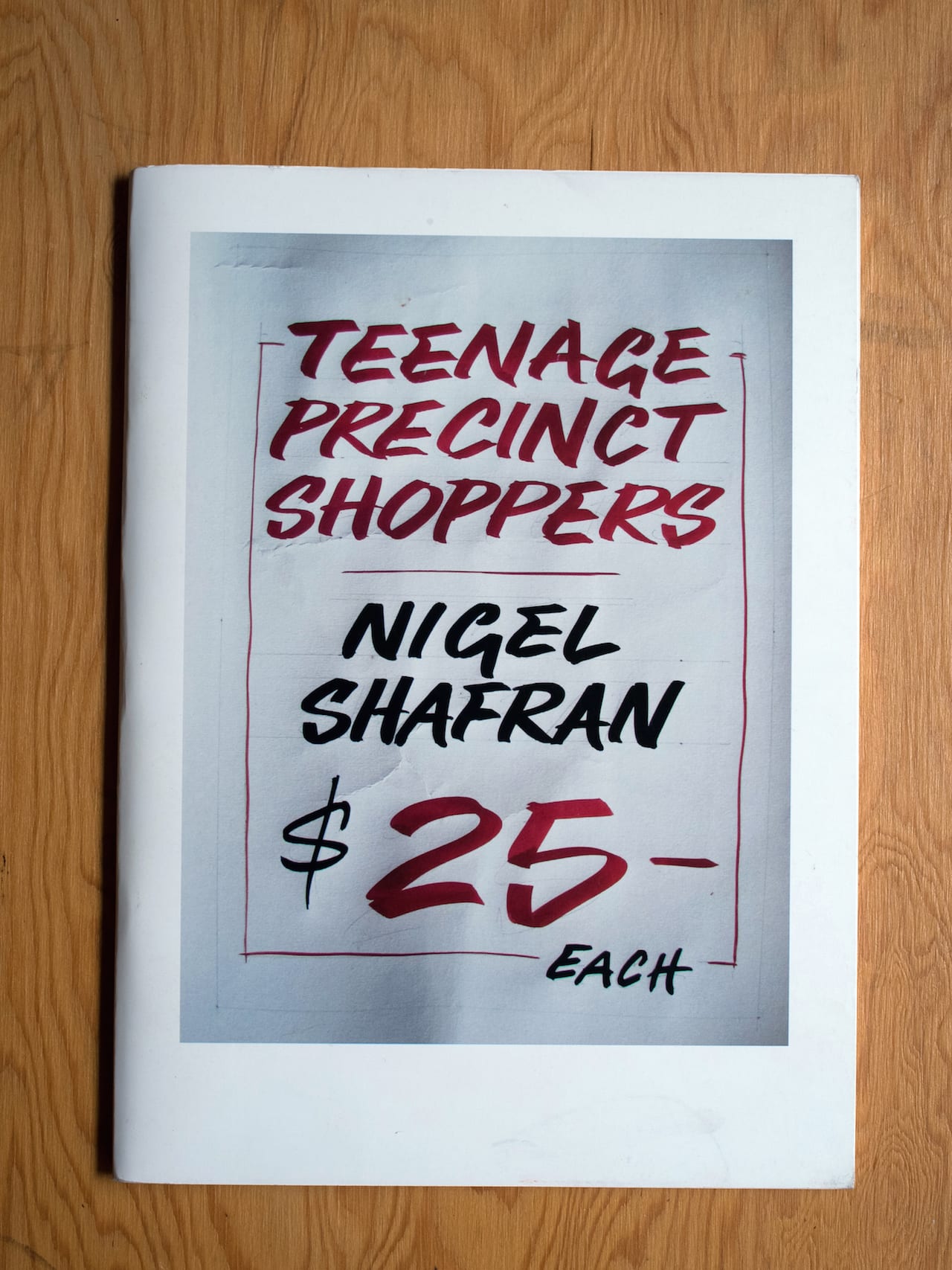

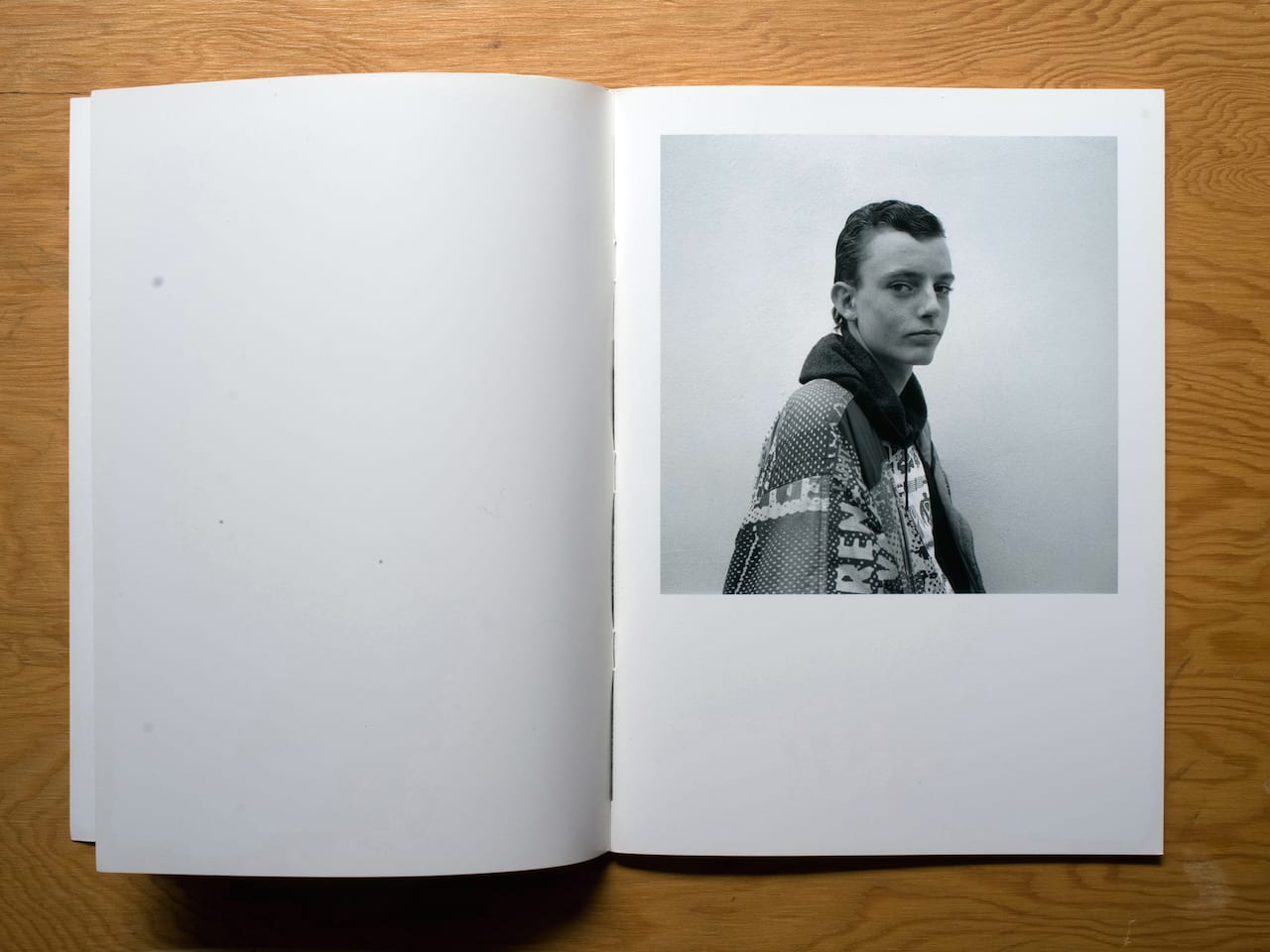

Coming up through style magazines in the 1980s, Shafran made his name with a story that appeared in i-D. But it wasn’t strictly a fashion story, unstyled, with a documentary approach, and capturing teenage precinct shoppers in Ilford town centre. In the mid-1990s he ventured into self-publishing with Ruthbook, photographs of his girlfriend shot mostly at home in her dressing gown, say, or blowing her nose, alongside details such as crumbs on a kitchen work surface, a pot on the stove, or a hair stuck on a bar of soap. Shafran hand-wrote the title, in pencil, on all 600 copies.

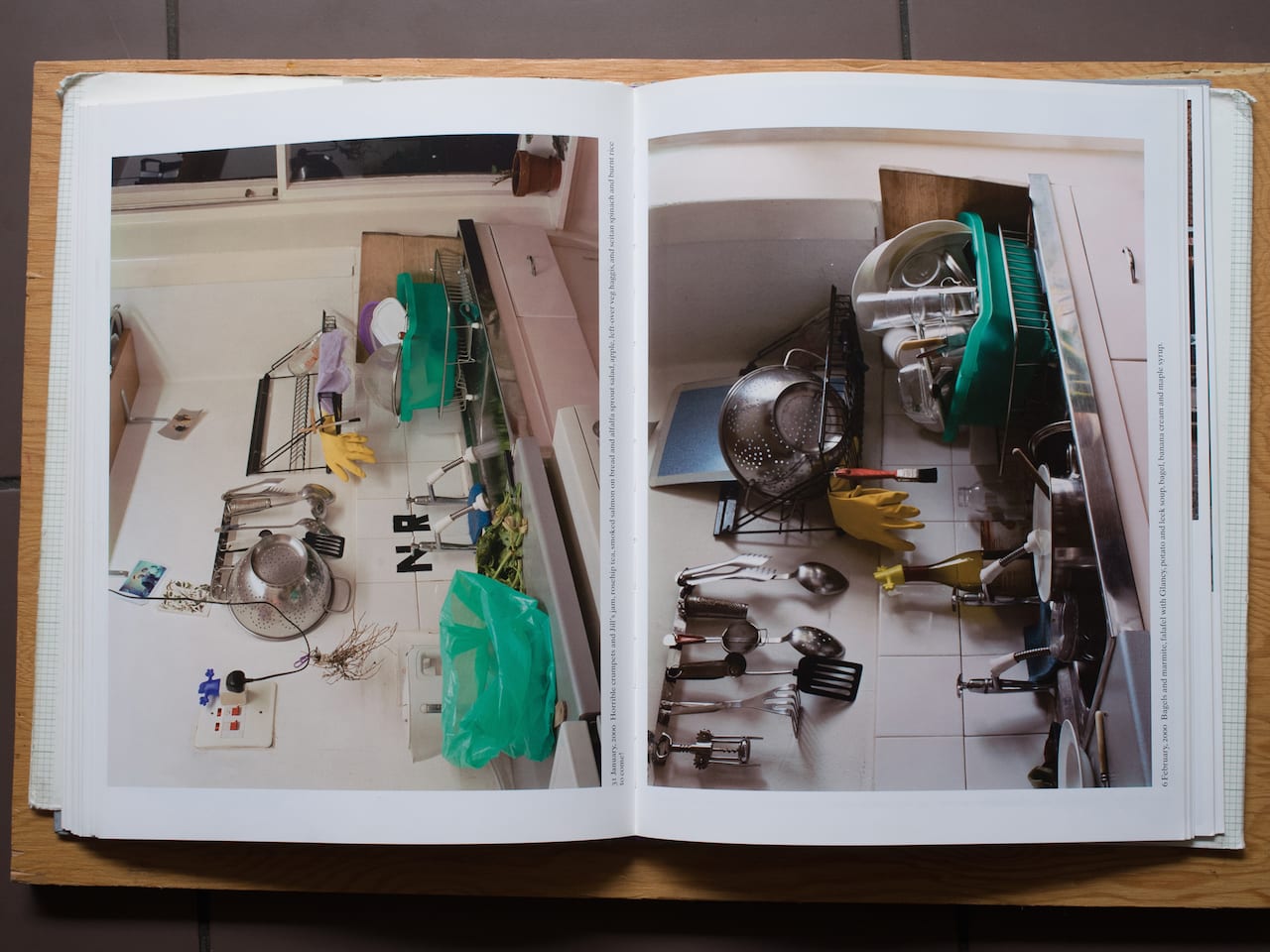

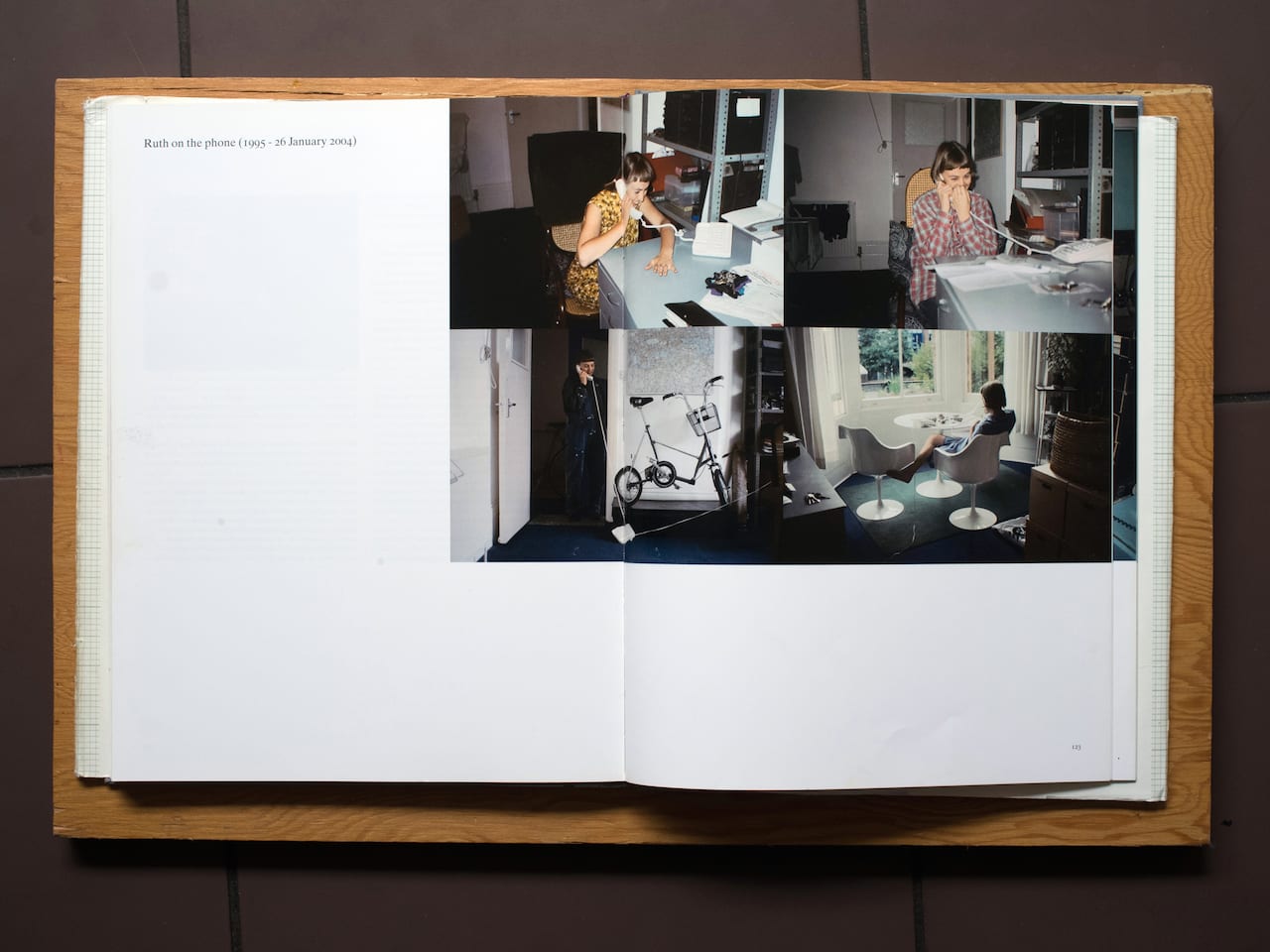

Further books and series have followed, all with similarly low-key subjects. One shows Ruth talking on the phone, another the daily routine of washing up on the draining board. Shafran published his work with Photoworks/Steidl in 2004, titled Edited Photographs 1992- 2004, a selection of images from 12 years of work, and in spring 2016 he’s publishing Dark Rooms with Michael Mack, presenting work shot over the next 10 years.

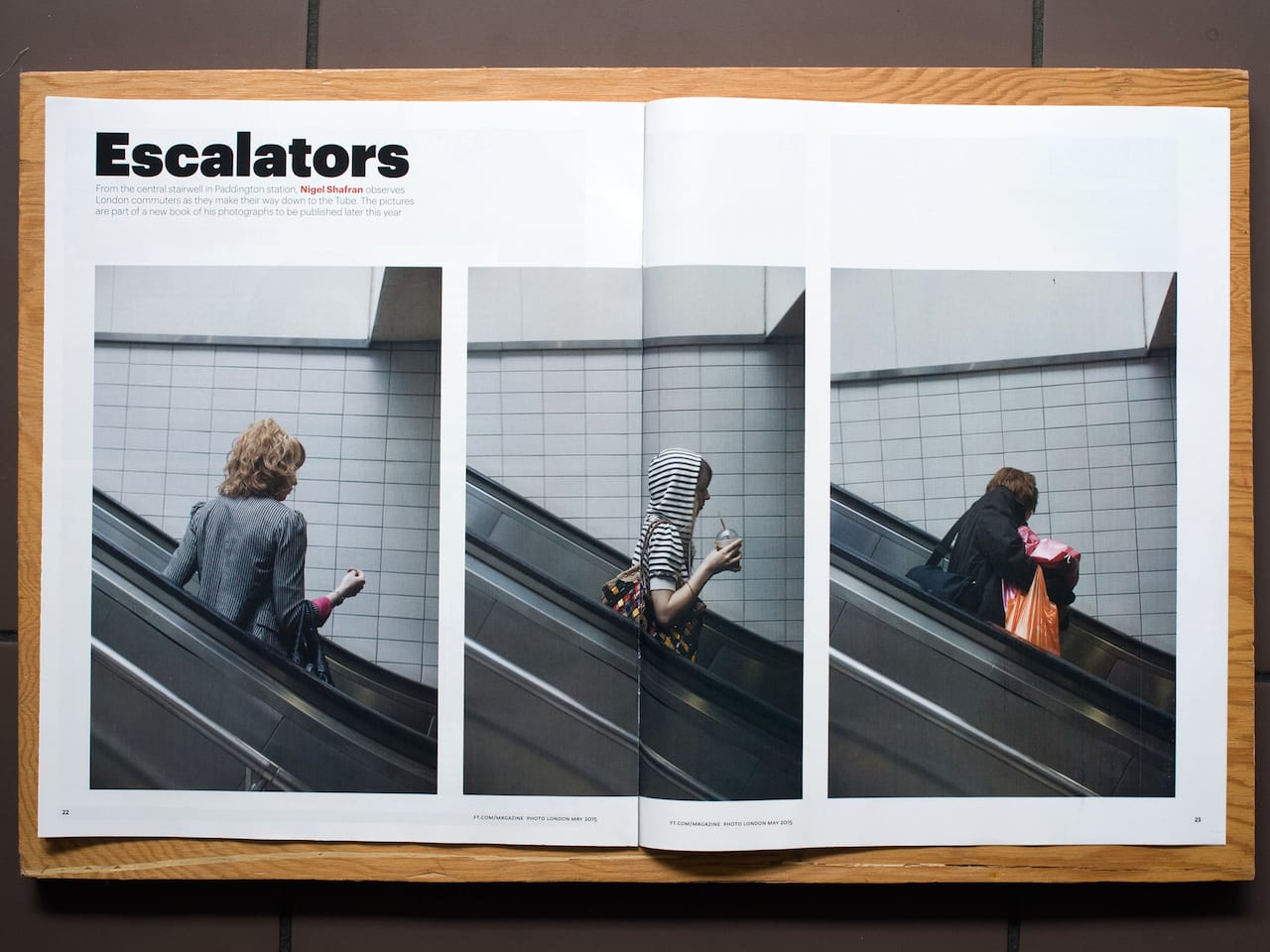

He shows me a PDF of it, and its intriguing collection, showing women on Tube escalators, food on supermarket conveyor belts, the flotsam and jetsam that washes up on the kitchen shelf. Some capture beautiful light, some don’t. They’re prosaic yet they aren’t at all, each portraying apparently everyday scenes. “It’s there, in front of you, you’ve just got to see it,” says Shafran. “If you’re lucky enough.”

He doesn’t much like to talk about his work, arguing that he communicates through images, not through words, and that he dislikes overthinking his photography. “I prefer to be instinctive,” he says. “If you make a kind of mathematical equation, it just kills it.

“I will be affected by something and then I’ll just want to communicate that in the simplest way, so there’s no barrier between what affected me and hopefully the way I put that in a picture. Pretty simple, no? Something I found effective – don’t get in the way of it, don’t fuck it up! Get out the way.”

It does sound simple but, like his photographs, it’s deceptively so. In photographing everyday elements and details, Shafran captures something of the fabric of our lives, the background noise that usually goes unnoticed, but which shapes us and our fate.

“Sometimes I see old photographs, and what’s interesting to me are the things on the edges that are not meant to be there,” he told Charlotte Cotton in the interview published in the book, Edited Photographs. “The soap packet, the bit of litter, the things we relate to and hold that everydayness.”

He goes on to tell Cotton that this interest doesn’t just apply to objects – people and their gestures, style and actions, conscious or unconscious, from how they cut bread to how they paint, are equally extraordinary, if you have the eyes to see it that way. They are “expressions of everything that’s us, of how we’ve been brought up or taught or learned”, he says; his images capturing the way Ruth props up sticks of rhubarb in a fruit bowl, or the way a woman turns to adjust her blouse on the escalator.

It’s an interest that reminds me of Georges Perec, the philosopher who tried to note down everything he saw in Paris’s Place Saint-Sulpice for three days in October 1974, capturing the “little pieces of everydayness”, as he put it, in a bid to discover who we are. Shafran deftly bats the suggestion away, claiming, “I’m not very clever, I promise you,” but he refers me to David Chandler’s essay, Partial Eclipse, included in Dark Rooms, which quotes Patrick Keiller’s reading of another French philosopher, Michel de Certeau.

“Keiller quotes de Certeau from The Practice of Everyday Life in a long passage that is worth repeating here,” writes Chandler. “The purpose of this work is to…bring to light the models of action characteristic of users whose status as the dominated element in society (a status that does not mean they are either passive or docile) is concealed by the euphemistic term ‘consumers’…

“Increasingly constrained, yet less and less concerned with these vast networks, the individual detaches himself from them without being able to escape them and can henceforth only try to outwit them, to pull tricks on them, to rediscover, within an electronicised and computerised megalopolis, the ‘art’ of the hunters and rural folk of earlier days.”

It seems apt and puts a new perspective on Shafran’s subject matter, on the teenage precinct shoppers, the supermarket conveyor belts, or the strange assortment of goods in charity shops, divorced from the gloss of their original advertising and packaging. “It’s the only kind of shop where the goods chose the shop rather than the shop choosing the goods,” Shafran told Cotton.

“There’s a visual connection with the car boot sale pictures as well – all the packaging that makes it a photograph you can date, has a place in history. I find it really interesting with the security that we invest in the things we buy, me included, and the effort that the stallholders take in displaying their goods. I find it admirable as well as visually intriguing.”

From this perspective it’s easy to see why Shafran has a slightly uneasy relationship with fashion photography, despite having started out assisting in this world and making his name there, and continuing to shoot for clients such as Loewe, and magazines such as British Vogue and Love. He’s also represented by M.A.P, one of the most prominent photography agencies in London, which also has Tyrone Lebon and Jamie Hawkesworth on its books.

In fact, he’s recently made something of a return to fashion after a few years lying low – years in which he told The Guardian that “fashion was not what I wanted to pursue, because of the way it depicts women, and the aspirational values it promotes, suggesting you shouldn’t be happy with what you have”.

In another interview, with DoBeDo, he states that “fashion photography, however much you want to dress it up as something else, is what it is – it’s a business of selling clothes, and I’m not very interested in that”.

He says he’s a hypocrite when I bring it up, and that he’d rather not talk about this work, but he also says that maybe now he feels “a bit more secure” about his own work, and that “maybe one informs the other slightly. I never thought that, but maybe it does”.

It’s a turnaround from some of his earlier interviews – from telling DoBeDo that Ruthbook was “the start of the way I work now, separating commerce and non- commerce” in 2009, and The Guardian that his Compost pictures were “the antidote to some of my previous work [in fashion]” in 2010.

Maybe, like many of us, he has to live with some contradictions, some compromises between what he wants to do and what he needs to do to earn a living in one of the most expensive cities in the world. Or maybe he has reconciled himself with commercial work and the possibility of being creative within its limitations.

Before I leave he’s keen to show me some of his photobook collection, for example, which includes several old company brochures; he also speaks highly of David Campany’s publication, Walker Evans: The Magazine Work. “There was a time when there was a necessity to do commercial work,” he says.

“Now, or more recently, it feels like that’s not something that’s done, but if it’s good enough for people from that time it’s good enough for me.”

Either way, he’s been able to put his own twist on his recent fashion commissions – a shoot for British Vogue, for example, featuring couture collections framed in the context of an imaginary shopping spree on Paris’s upmarket Avenue Montaigne. A literal take on “the business of selling clothes”, as Shafran puts it, it’s a funny, slightly ironic, story and one that also, perhaps, evokes the ghost of the teenage precinct shoppers.

Similarly, Shafran’s shoot with Cara Delevingne and Edith Campbell for Love pictured the models behind the scenes rather than highly stylised for a more typical studio shoot, with pictures of them changing light bulbs or reading the paper.

Shafran is “not going to complain” about getting these commissions, but says there is a clear dividing line between them and his personal work, which is the fact that he can’t choose what to shoot. “The difference doing commercial work is that I don’t pick the subject,” he points out, and he adds that if it’s a commercial job he also doesn’t choose how it’s presented, and “the context is important”.

“In a commercial magazine [it will be] next to adverts, next to text, next to other distractions,” he says. “They’re all decisions you make about your work, and if that’s taken out of your hands, maybe it’s not completely your work any more. How your work is seen is one of the decisions you make. Take Leni Riefenstahl – great photographer, slight problem she decided to do the Nazi Olympics. You can’t take that away, you have to be responsible for what you do.”

Shafran republished the teenage precinct shoppers as a book in 2013, for example, presenting the images differently to their first appearance in i-D. I ask him if books are his preferred medium; he says that he hasn’t thought about it, but he supposes so. “People go on about books, and they’re so popular at the moment, but it’s still quite a good way to see work and it’s affordable,” he says.

“People can see it in a way that somebody put it together, in a sequence, and a decision can be made of how it’s done. But some pictures to me don’t look that different in a book to on a wall. Robert Adams’ pictures don’t look that different to me in a book or on the wall of a gallery.”

Shafran also spun out another book from a commission recently, repurposing out-takes from V&A company report shoots for the book Visitor Figures. He says that commission was “a very nice one to be able to have” and “the nearest thing I guess to my work”. The museum was probably expecting he’d make pictures for a couple of weeks, he laughs, but he ended up staying four months, shooting in the galleries and behind-the-scenes, heads of departments and school children, and key scenes and incidental moments.

“I always knew that was going to be more, because luckily I’ve always had a very nice connection to the V&A,” he says. “When I self-published Ruthbook, one of the best things to happen to me was Mark Hayward-Booth called me in back in 1995 or ’96, and they bought the whole set for £250. It was very nice to have a form of validation at that age, and they’ve been very supportive since. So when this came up I knew something was going to happen like this.

“It was originally meant to be all of this,” he adds, going to get the resulting report and pointing to the usual illustrative pictures that run through the text. “But then the directors went, ‘Well, actually, it’s a bit too nutty’, so they ended up giving me this funny section at the back…It’s a nice commission to be able to have. Because I’m just basically a pain in the arse, I’m not going to do anything I’m not going to do.”

Martin Barnes, senior curator of photographs at the V&A, puts it rather differently in his introduction to the report, commending “the fact that Shafran approached one of the world’s greatest museums with the same democracy of vision that he has applied in previous projects, to stacks of washing up in his home, or to the contents of his father’s garage… [he] has a perceptive eye for places and moments that are so familiar or unremarkable that their beauty often gets overlooked”.

“He is not drawn to anything conventionally spectacular,” Barnes adds. “He will not reinforce a polished corporate vision. But you can trust him to show you something lyrical, significant and revealing about places and people you think you know. Though his pictures are of the moment, and in the moment, half of his awareness is already concerned with posterity. As a result, his photographs are filled with acceptance, tenderness, humour and a dose of melancholy.”

And that eye for posterity is key, because in shooting the everyday, Shafran is trying to shoot life as we experience it now – and as we will not experience it in future, and will therefore find quite fascinating. That’s why he’s interested in clothes, although he’s not into high fashion, and why he’s interested in products, although he’s wary of consumerism. Because in the ever-changing products produced in our society, these things quickly become outmoded.

“Keep in mind that including contemporary cars, fashion, packaging, etc, will date your photographs,” he advised image-makers in The Photographers’ Playbook, Aperture’s 307 Assignments and Ideas, which was published in 2014. “Look at the present as if it were the past – as if you are the future and ‘now’ was then.”

“The photographs I make are connected to the magic of photography to transcend time,” he told Cotton back in 2004. “It’s like a time tunnel – some 19th-century photographs take you back to a something that you know is past but has been kept alive and has an energy. It’s a connection between then and now.

“When I’m inspired to photograph something, that’s what I try to respond to. I try to be open to seeing in this way. It’s about keeping something alive, in a sense.”

It’s a point Dark Rooms obliquely references on its front cover, which features hand-drawn curves that nod to the film poster for A Matter of Life and Death, the Michael Powell/Emeric Pressburger film in which time stands still for a fighter pilot on the brink of death. It’s also referenced in many of the images, which freeze supermarket conveyor belts or escalators, or the peculiar, ever-changing constellations of stuff on the kitchen shelf. It’s something that’s marked out his photography from the start but, perhaps, it’s more prominent now that he’s older, has had a son, and his parents have both died.

And it is in this, perhaps, that his images do something that many of us hope for with our own snaps, which capture friends and family in moments that we know will disappear forever. When I suggest this to Shafran, he’s happy I’ve made the comparison. “Some vernacular set of pictures is more interesting than work that has a kind of grand scale,” he told DoBeDo in 2010.

“Flowers For____ is at the beginning all the flowers that were given for Lev when he was born. We didn’t have enough vases so we ended up sticking them in biscuit tins and everything. And it wasn’t done for any great artistic purpose. I just liked it and thought I’d photograph it to keep it, otherwise I would have forgot about it,” he tells me. “That’s the best thing I’ve said all day! That’s basically it, isn’t it?”

“I suppose I am a family photographer, really. They’re the most important pictures for people, aren’t they? I’m just a very good family photographer. I like that. I’m happy to be that.

“That’s not bad,” he adds, looking at a video he’s shot of Ruth at home. “It’ll look better in 10 years, maybe 20 years.”

www.nigelshafran.com Nigel Shafran Work Books 1984 – 2018 is going show at Sion and Moore, 4 Herald Street, London E2 6JT from 18 May – 07 June. Prints from Shafran‘s Teenage Precinct Shoppers series will also be for sale. The website www.sionandmoore.com will be going live soon.