Fractured Stories – an exclusive British Journal of Photography commission supported by Ecotricity – will give one photographer the opportunity to capture the untold stories surrounding fracking in the UK. The selected photographer will receive, among other prizes, a £5,000 project grant. To mark the opening of the competition, British Journal of Photography is publishing a series of editorials relating to the subject.

The Marcellus Shale – a stretch of rock dating back approximately 384 million years – extends deep underground. Beginning in upstate New York it moves south through Pennsylvania, onto West Virginia and then west, under parts of Ohio. Spanning 600 miles, and reaching thicknesses of 270 metres, the formation is the largest natural gas field in America and one of the largest in the world. Harbouring an estimated 84 trillion cubic feet of undiscovered, technically recoverable natural gas, today, it is home to thousands upon thousands of fracking sites, with many more being developed each year.

“When I started this project, the major US media outlets were gushing over themselves trying to do story after story about the fracking miracle,” says the award-winning photojournalist Nina Berman, referencing her participation in the Marcellus Shale Documentary Project. Initiated by the photographer Brian Cohen in late-2011, and comprising Berman and five other photographers – Noah Addis, Lynn Johnson, Scott Goldsmith and Martha Rial – the MSDP crisscrossed the Pennsylvanian portion of the Marcellus Shale, along with areas in neighbouring states, investigating the myriad social, environmental and economic impacts of fracking playing out along it. “I know that the work has changed the conversation,” she continues, “you don’t see such positive stories around fracking anymore.”

Hydraulic fracturing, or ‘fracking’ as it is more commonly known involves pumping a mixture of water, sand and chemicals at high-pressure deep below ground to break apart rock, and extract natural gas and oil. Offering energy security, a source of new jobs, and, what some refer to, as a ‘bridge fuel’ to a renewable energy future, on paper, fracking presents itself as an attractive solution to America’s, and indeed the world’s, energy challenge. But, as Berman and her colleagues discovered, the reality on the ground is very different.

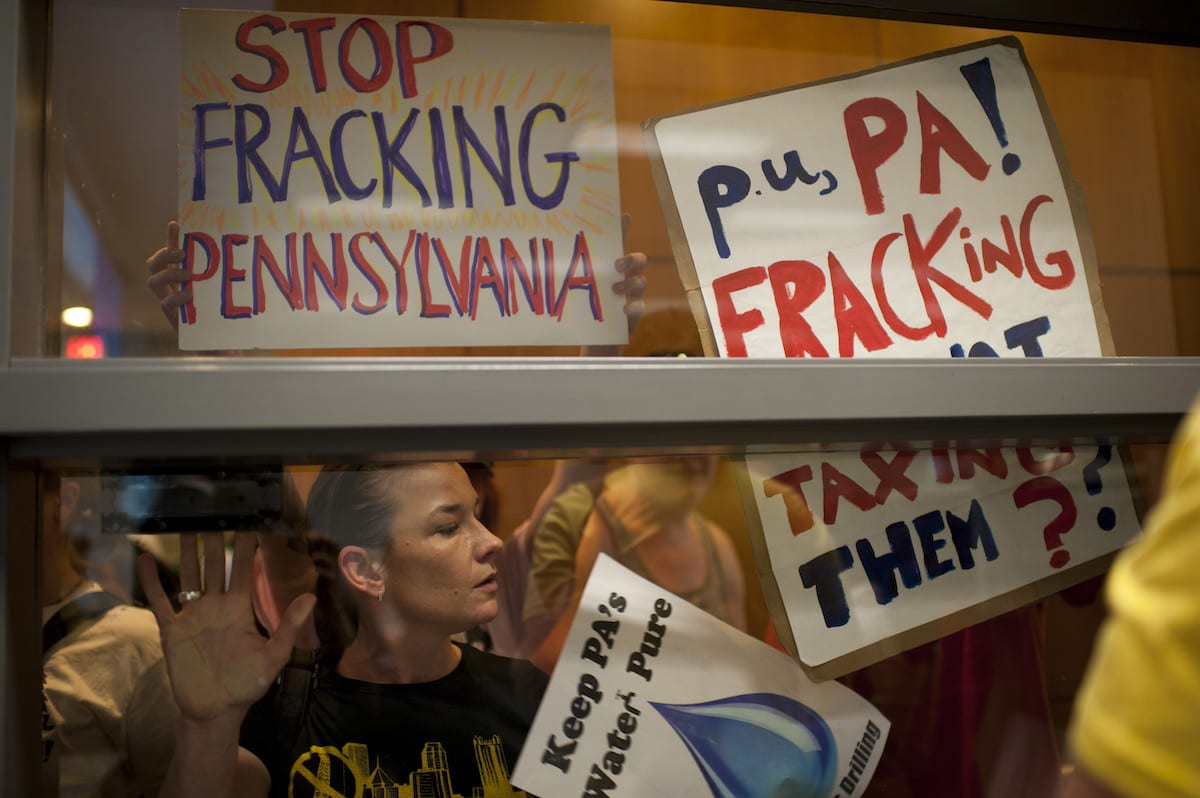

“The gas industry and its political proxies are churning out propaganda every day to try and convince the public that fracking is a clean source of energy,” says Berman. Completed over five years, her resultant body of work – Fractured: The Shale Play – stands as “a warning” against the process. “Fracking is not a clean source of energy,” she says “it is dangerous, filthy and poisonous.” Indeed, since fracking began in earnest, its impacts on the environment have become a widely debated issue. Wells can produce hundreds of millions of litres of wastewater laced with toxic chemicals and carcinogens. With shady government legislation surrounding the monitoring of fracking’s effects on water and air quality (the process is exempt from numerous statutes including the Safe Drinking Water Act and Clean Water Act), water contamination has become a serious issue in Pennsylvania, and further afield.

Through her photographs, Berman addresses these myriad concerns. “I looked at the human health impacts of air and water contamination, the negligence of regulatory agencies to properly monitor fracking’s effects and the reality of local activists taking on that role,” she says. “I looked at gas refugees – those who have been driven out of their homes by the industry – and the terror and anxiety of those who remain: should they leave, should they drink their water?” Her images work to address these overwhelming, somewhat abstract issues, on a more personal level. Studying a map of Pennsylvania, she chose to explore areas with lots of drilling activity She met with locals, who she visited year after year, following their stories as they unfolded.

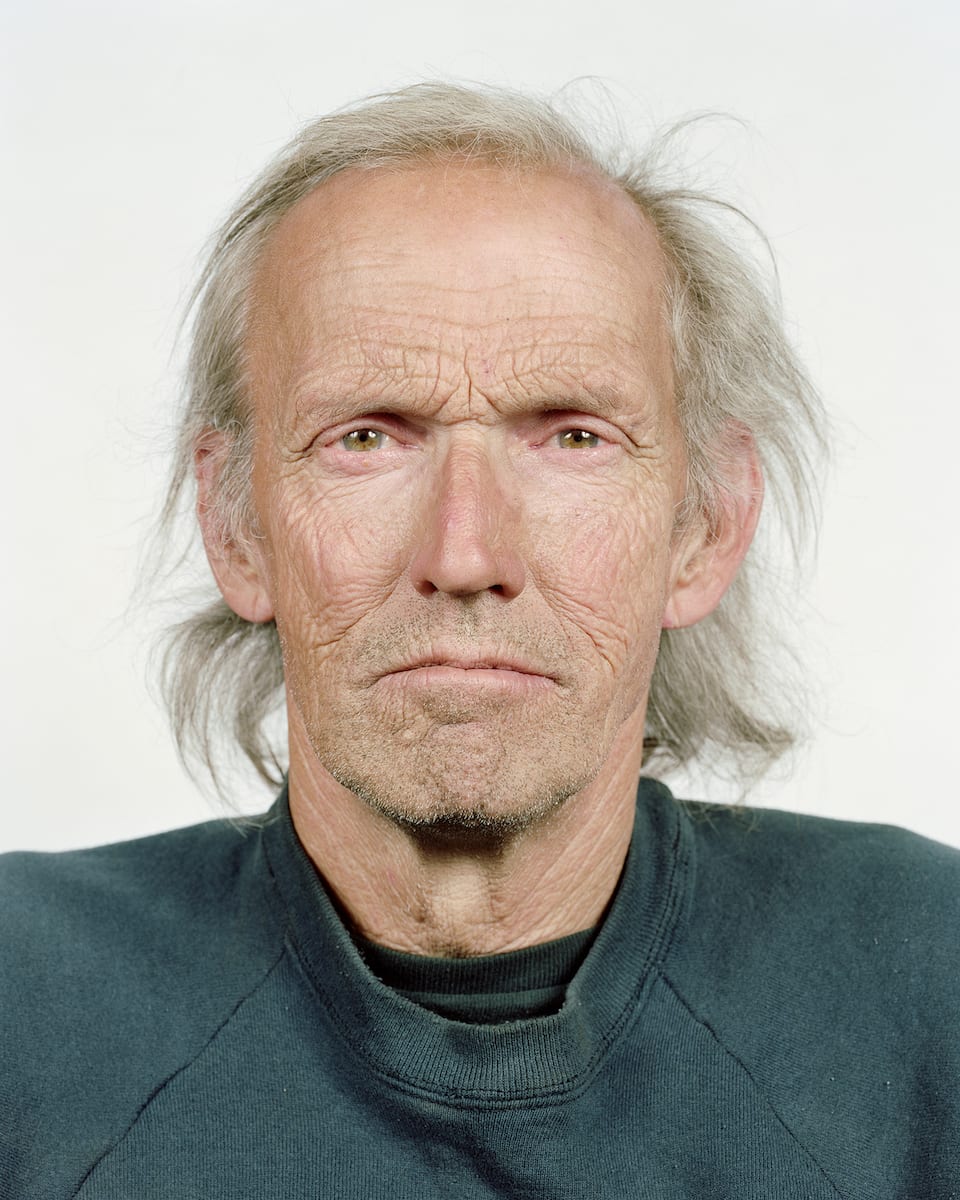

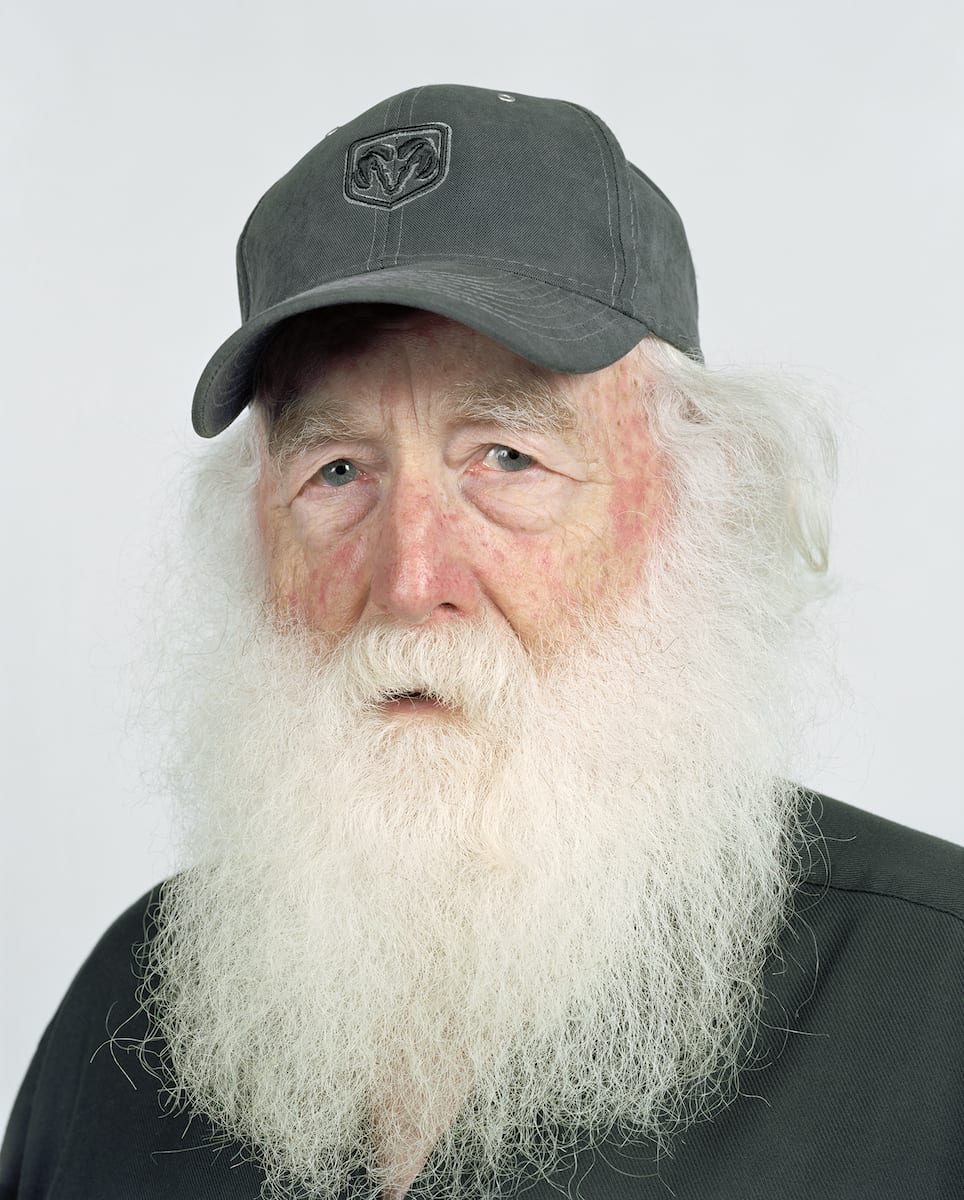

Like Berman, Noah Addis – who was invited to join the MSDP in 2011 – also focused on the people and places caught up in the fracking boom. However, in contrast to Berman, who captured individuals going about their everyday lives, Addis actively chose to remove his subjects from their environment. Instead, he photographed them with studio lights against a white background. “I know that this may seem counterintuitive because the environment is such an important part of their story,” he explains, “but I wanted to focus on the people themselves. They’ve been through so much, and I think it shows on their faces.”

Both practitioners grappled with how to document fracking’s impact on the landscape. “Fracking is a difficult subject to photograph, since the actual process takes place deep underground, and many of the environmental effects are invisible,” explains Addis. Drawn to the influx of industrial infrastructure in otherwise rural areas – from gas processing plants and pipelines, to steel mills where drilling pipe is made – Addis’ images bestow these emblems of industry with an alluring aesthetic. But, the stills are also laced with a darker message. “The infrastructure depicted raises questions about what will happen when the wells no longer produce gas,” he explains. “Energy is a boom-and-bust business; when the natural gas boom is over, we will likely be left with a huge mess to clean up.”

Berman differed in her approach. “Industrial activity is visually dramatic,” she says, “yet, the activity is fraught with toxic impacts, presenting a visual paradox.” Negotiating this paradox, Berman endeavoured to capture the visual markers of the industry within the landscape in an unsettling manner. Working at night enabled her to achieve this. “This is when the landscape got very weird,” she explains. “After dark the rigs would light up like bizarre skyscrapers, and, if there was flaring, the sky would turn orange and apocalyptic.”

Much like the themes explored in the Marcellus Shale Documentary Project, Fractured Stories will give one photographer the opportunity to investigate fracking in the UK. As in the US, the subject remains a divisive social, political and environmental subject. However, despite the UK’s vast shale gas reserves, not a single well has been fracked since a ban on the process was lifted in 2013. This year, the government has made renewed efforts to encourage the development of drill test sites throughout England, making it an important moment to explore the subject. The selected photographer will win, among other prizes, a £5,000 project grant; travel and accommodation expenses will also be covered.

In America the industry shows no signs of slowing down, with experts predicting that a major second-wave of US shale production is imminent. Despite, updated regulations, fracking continues to negatively affect communities and environments across the country. The work of the MSDP exists as a powerful record of the impacts of fracking during a critical period in the industry’s history. “I want people to look at my photographs and then do everything possible to fight this form of energy production,” says Berman. Addis holds a similar view: “there is huge value in keeping the conversation going, and photography is pretty good at that.”

Fractured Stories is now open for entries! The competition is free to enter and open to all photographers. Don’t miss out – the deadline for submissions is Tuesday 10 July 2018, 11:59 (BST).

–

Fractured Stories is a British Journal of Photography commission made possible with the generous support of Ecotricity. Please click here for more information on sponsored content funding at British Journal of Photography.