Four years ago, when we first featured Sim Chi Yin in our talent issue, she was a relative newcomer to the photography scene, though her resumé was already looking impressive. Tipped by Sarah Leen, director of photography at National Geographic, she seemed an assured bet, destined to do great things with a camera.

Fourth-generation overseas Chinese, she was born and grew up in Singapore before studying history and international relations at the London School of Economics on a scholarship. Returning home, she spent her twenties and early thirties on the road, working fiercely hard as a foreign correspondent for The Straits Times, Singapore’s respected daily, rising to become the paper’s Beijing correspondent.

“Plenty of people warned me it was crazy to throw away a decade-long career as a foreign correspondent,” says the 39-year-old, speaking from her home in the Chinese capital. And the move into photography was, from afar, a seamless transition. Her first major work, The Rat Tribe, a documentary series detailing the lives of blue-collar workers in Beijing, was shown

at the 2012 edition of Rencontres d’Arles, while her coverage of the Burmese Spring was exhibited by Oslo’s Nobel Peace Center later that year.

A third series, Dying to Breathe, which explored Chinese gold- miners living with occupational lung disease, was supported by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting and triggered a nomination for the 2013 W Eugene Smith Grant in Humanistic Photography. After inviting her to be part of their mentoring programme, VII photo agency made her a full member (although she left in 2017).

The major news organisations quickly came calling. She gained assignments for publications such as Le Monde, National Geographic, The New York Times, and Time. She was almost constantly on the road, working feverishly. She recalls an English friend asking her how her career was going. “I’m juggling spinning plates,” she said. “I think you’re mixing your metaphors there,” he said. “I know,” she responded. “I mean to.”

It’s disconcerting to think how years of work and effort, of countless hours spent practising and honing a skill, can be wrenched away from any of us in just a few minutes of misfortune. It’s also, for any of us used to good health, troubling to consider how reliant we are on the basic functionality of our bodies. A photographer, for example, needs to be able to hold a camera, to have the strength to frame a shot and time the click of the shutter in the heat of the moment. Shorn of that basic ability, what are we left with? Early one morning in May 2015, Sim had to face that exact question.

She was on assignment for a French newspaper, travelling to the Tumen Economic Development Zone, a government-owned complex of Chinese factories on the edge of the border with North Korea. Tumen employed North Korean labourers who, with state sanctioning, would be sent to live and work in the economic zone. The brief was to capture how North Korea and China trade. This place seemed like the perfect microcosm for that complex relationship – the makings of great pictures.

Entering Tumen with her driver and colleagues from Le Monde, she failed to spot a sign that read: “No smoking, photography, or practising driving”. As they approached the factories, the car passed a small group of women in black jumpsuits, knelt by the roadside picking weeds from the ground. Sitting in the driver’s seat with the window wound down, Sim instinctively raised her camera and fired off a couple of shots. “Almost immediately, the women turned around, ran towards the cab, and reached into the car,” she wrote in an article for ChinaFile, recounting events.

“My hand, with fingers on the camera grip and shutter button in shooting mode, was stretched outside the car window. We were now surrounded by the women workers. Six or seven of them were pulling on my camera… The strap [was] wound around my thumb, making it impossible for me to release the camera…”

She can remember the thumb on her stronger right splitting in two places. Blood was pouring from the wound, yet the women would not give in. “For a second, I locked eyes on one of the women pulling my camera… She was consumed by a fury that I had never encountered before, a blind hatred, an uncompromising determination. I wondered, what drove these women? What were they thinking?”

By the time the camera had been wrested from her grasp, Sim’s thumb had been ripped from its socket, her ligaments turned to spaghetti. From there, the situation didn’t get any easier. The women were North Korean. Sim expected them to smash her camera, but they instead, “with great discipline, handed it immediately” to a frowning, official-looking man who had arrived on the scene. When the police arrived, the camera was dutifully turned over, and Sim entered a vortex of suspicion, indecision, bureaucracy and misdirection.

Deprived of ice to ease the swelling or water to clean the wound, her thumb ballooned to twice its size as a gaggle of policemen and exterior officials – evidently from China and North Korea – gathered at the police station, trying to work out how to handle a situation that involved a Chinese-Singaporean photographer, a French reporter and North Korean workers at a Chinese-run factory.

As Sim waited for news, she noticed her attackers – who studiously ignored her – pass around a small red badge engraved with the bust of Kim Il Sung or his son, Kim Jong Il. She observed one of them take it to a corner of the room and seem to talk to it – as if she were talking to Kim himself.

When she eventually made it to the local hospital, Sim Chi Yin was told a man had visited the industrial park a month previously. He had taken pictures with his mobile phone and was also attacked. A chunk of flesh was bitten from his hand. Returning to the police station, she says it was made clear they would not be let go unless they promised not to press charges. Giving in, she was on a flight back to Beijing two hours later, where a doctor ordered an MRI scan.

“As I waited for the results, one of the policemen from Tumen called. ‘Hello, Journalist Sim,’ he said. ‘We hope your hand is better. It’s best if you don’t get surgery.’”

She did have surgery, twice, followed by physiotherapy that continues to this day. Le Monde’s insurance only covered the initial costs of surgery, leaving Sim to pay the rest of the expenses. All in all, she estimates she lost 12 months of earnings, and it took her a full two years before she felt confident and capable enough to work again. But, however traumatic the event, and however painful the aftermath, that day on the border with North Korea has allowed Sim to realise parts of her life, and her photographic practice, that might otherwise have remained veiled.

“It was a very stressful and painful time for me,” she admits. “But I decided to see it as a wake-up call. It allowed me to think carefully about how I was spending my time, where I was going, what I was contributing. The injury coincided with me becoming aware of my age, and I thought to myself, ‘There’s only so many more creative and productive years you have left’. I decided I wanted to work differently, to find a new visual language – a slower, more patient, more deliberative style of photography.”

It’s a theme she expounded on in May this year at an awards event in New York commemorating her as the seventh winner of the Chris Hondros Award, an accolade created in memory of the late Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist who died alongside Tim Hetherington in a mortar attack in Libya in 2011. She used her acceptance speech to thank “the mentors whom offer moral support as I stumble and shuffle along this path that is not straight, paved or breadcrumbed. And the dear friends who talk me through heartache and cheer me on as I fight through the confusion of a self-directed life.”

Yet she also used the speech to recognise that her work, and her life, are at a crossroads. “Even in the seven quick years I’ve been a full-time photographer, the way images are being consumed has changed significantly,” she said. “A photoessay I spent much of a year working on runs online and seems to be consumed and spat out in two hours. How do we be useful photographers any more? How do we speak in a very noisy and distracted room – and be heard? And having got their attention, how do we make people care?”

She pointed to the influence of Hondros and Hetherington, noting how they adopted a more thoughtful approach, “fluidly multidisciplinary and experimental”. And with that in mind, Sim’s new focus is on creating works with an emphasis on “impact over reach”. The foremost example is the series she made for the Nobel Peace Prize, illustrating in her own voice the work of the 2017 winner, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons.

It was the first major commission Sim had taken on since her thumb was ripped, and having been awarded the assignment before the winner was announced, she’d anticipated photographing the work of an individual, and was planning accordingly. To hear the prize was awarded to a diffuse, multinational organisation, one mostly made up of volunteers working out of more than 100 countries, presented a clear and obvious issue. “To be frank, the organisation is mostly campaigners with banners and placards,” she says. “It’s people writing emails, or newspaper columns, or going on Twitter.”

How could she photograph such an abstract thing – a weapon that could cause genocide in an instant – in a meaningful, thoughtful manner? What’s more, how could she take on the issue without being seen to take sides, or by hectoring people about who was in the right and who in the wrong? It is estimated that North Korea has tested nuclear weapons on six separate occasions over a decade, while the US – the only country ever to use the weapons – carried out more than a thousand similar tests between 1945 and 1992.

“Who gets to call who a rogue state, and who decides how many warheads are too many?” she asks. “I decided that if I was to invite people in, I had to create a suspension of moral judgement, and that meant creating a suspension of place.”

With what could be regarded as beautiful serendipity, an image of the North Korean borderlands taken the day before she was assaulted provided the eureka moment for her remarkable study of the pervasive threat of nuclear weapons on our collective psyche. Sim had been invited to Oslo to try and agree on a unified conceptual approach to the exhibition. During her preparatory research, she recalls looking at archival military pictures of the scarred and pockmarked landscape of America’s largest nuclear test site in Nevada. A little later, she decided to revisit the photographs she had made on that fateful trip to Tumen.

She honed in on an image she had photographed of the North Korean landscape, taken through barbed-wire fencing on the Chinese side of the border. The image was incidental, a momentary snapshot she had never had cause to seriously consider before. Yet two years later, she placed the screen of her mobile alongside the image of the Nevada test site on her desktop.

“And they looked similar,” she says. “There was a parallel there, a sense of a continuity between the way both places looked. An idea was there, a meaning emerging. I decided I would look for parallels – both visual and symbolic – between these landscapes.”

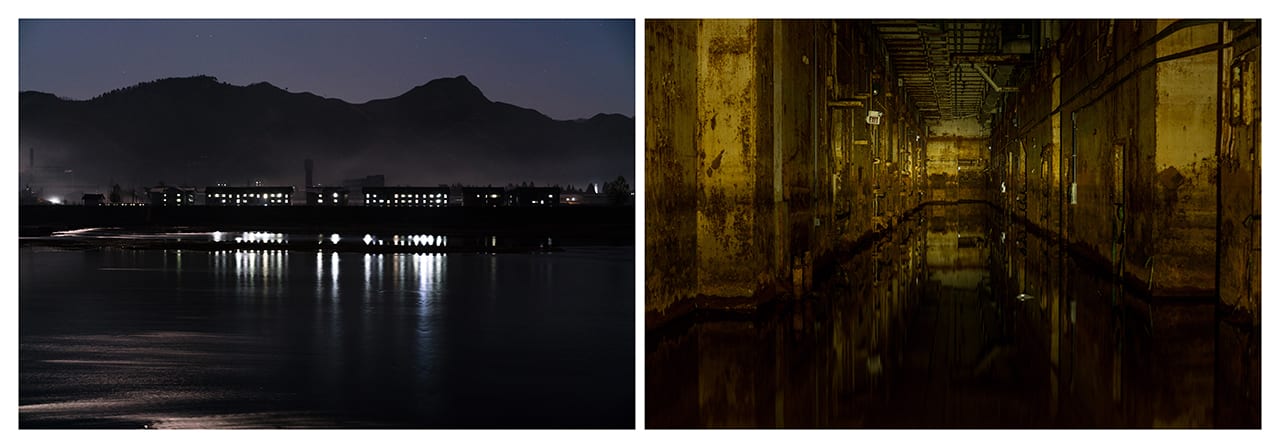

The series, which she titled Fallout, saw Sim and two producers drive more than 6000 kilometres along the China-North Korea border and through six US states in the space of two months. In Asia, she searched out locations closest to North Korea’s nuclear test sites, missile-manufacturing facilities and munitions bases, photographing the landscapes that surround them. “I travelled back to the place where I had been attacked,” she says. “I had to confront those traumas.”

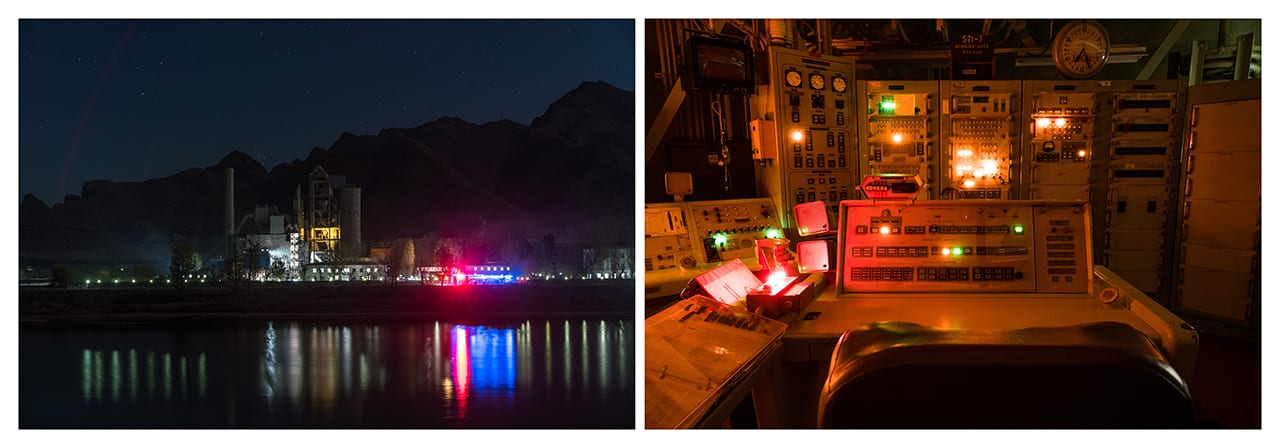

In America, she photographed from the snowy wilderness of North Dakota, where a pyramid like military radar complex looks out from a high vantage point, to the cratered nuclear test site in the Nevada desert. For the resulting exhibition, which launched at the Nobel Peace Center museum in Oslo, Norway, after the Peace Prize ceremony in December (and continues until November), she placed the images from the two countries side by side, creating a series of diptychs that seem to mesh and tessellate with each other. “Which is America, which is North Korea? The answer is not always obvious,” she says.

Meanwhile, Sim has various long-term projects on the go, including Shifting Sands, focusing on a natural resource for which demand is rapidly outstripping supply. Her homeland, the small

but populous island of Singapore, is the world’s leading importer of sand. “Its thirst is mainly driven by its appetite for land reclamation,” she explains. “It has created almost a quarter of its territory [more than 50 square miles] out of the sea over the decades.”

She began photographing the project last year, on the back of a New York Times Magazine assignment, and a residency with the Singapore-based Exactly Foundation. “With rapid urbanisation and massive land reclamation around the world, there is now a growing global shortage of sand – a resource that, almost counter-intuitively, is finite,” she writes in her statement. “What does that mean for cities like Singapore going forward? How should we view this piece of global story?

“In this highly lucrative sand trade (so attractive there are sand mafias), rich cities are developing at the expense of their poorer neighbours – the growing global income gap writ large. Seen another way, the wealthy are buying bits of territory and moving it where they want it.”

Sim has overseen another exhibition earlier this year, one of much more consequence to her own life. Opening at the Jendela Gallery during Singapore Art Week, she showed for the first time a series titled One Day We’ll Understand, an exploration of the Malayan Emergency of 1948 to 1960, “a 12-year war in all ways but name, as the British fought against Malayan communists.”

The exhibition, which was part of a group show alongside Bangladeshi photographer Sarker Protick and Vietnamese painter and video artist Thao-Nguyen Phan, explored the contemporary impact of colonial legacies. Sim travelled to China, Hong Kong, Thailand and Malaysia to interview and photograph people from her grandfather’s generation who had experienced and survived the Malayan Emergency, photographing their treasured personal items and finding the landscapes they recalled in their stories – “landscapes of trauma and conflict”.

“On the trail of ghosts in the jungles of Malaya,” is how she terms it. But the photography Sim showed is, in fact, only a small part of a much larger, more complicated and ongoing family history series – one which centred around the shrouded story of her grandfather. In 2011, Sim’s mother showed her a photograph of him, a gentle-looking man called Shen Huansheng, dating back to the 1940s. Wearing a white cotton shirt, he smiles towards the lens, and from his neck hangs a camera. “I was very struck by it,” she says. “I had never known there was another photographer in the family.”

Indeed, Sim knew little of her grandfather, because he was barely mentioned by the family. He had been purposefully forgotten, his life an unspoken taboo. She began to dig, and discovered her grandfather, a former businessman and editor of a left-leaning newspaper, who had been imprisoned and then deported from Malaya by British colonialists, returning to Gaoshang, his ancestral village in Guangdong province, South China.

That same year, at the beginning of her career as a dedicated photographer, she decided to retrace her grandfather’s steps, travelling to Gaoshang and connecting with relations who she had never met before. There, she began to piece together her grandfather’s story. A month after arriving, he had joined the Chinese Communist Party – an act that would have been seen as a terrible crime in Malaya – before being captured and executed by Nationalist forces in 1949, just a few months before the Communist Revolution swept the country.

Titled For This My Grandfather Died, Sim’s photographs of her ancestral village are remarkable, capturing in unsentimental terms the demands of living in this simple, isolated farming village – a possible road not taken in her own family history. But she also captures how her grandfather is, to this day, remembered and revered as a martyr. She photographed a six-foot tall obelisk that marks his grave, and a faded, barely visible official portrait she discovered – maybe the last photograph ever taken of him.

Throughout the series, an unofficial history starts to quietly emerge, like the faded marks of a palimpsest. “He had died for communism,” Sim says. “But the family never accepted it. The family was ordered to forget him.”

Returning home, she showed her photography to her father, uncles and aunt. It sparked a reconciliation. After some soul-searching, the family returned to their ancestral home to pay their respects to the man they were forced to forget. And if anything exemplifies the power of photography, then this is it. Yet Sim is continuing the series, after revisiting its roots at an artist residency with Docking Station in Amsterdam last year.

“It has become a research, archival and visual project delving into trauma, memory, representation and historiography,” she says. “The project spans photographs, oral histories, archival material, artefacts, film, song, text, and will take me some time yet to finish.”

With her newfound deliberative, meditative approach, it seems likely Sim will create something very special. It’s difficult to say what those North Korean women had in their mind that May morning three years ago – did they feel obligated to attack Sim in such a way, or did they just feel a hatred towards a woman so curious and free, creative and ambitious? Either way, her defiant reaction demonstrates a remarkable resilience from a prolific talent.

chiyinsim.com Fallout is on show at the Nobel Peace Center, Oslo, until 25 November as part of its Ban The Bomb exhibition nobelpeacecenter.org It is also showing at Cortona On The Move, 12 July to 30 September cortonaonthemove.com and will be installed as a solo show at the Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore from 20 July – October 2018 under the new title Most People Were Silent. This article was first published in the July 2018 issue of BJP.