When Robin Hammond started work on his project Where Love Is Illegal, he changed his approach to photography. Shooting members of the LGBTI [lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex] community who have faced persecution and punishment in countries in which such prejudice is enshrined in law, he relinquished much of the creative control to the sitters.

Up until then, he’d worked in the tradition of great photojournalists, committing extended periods of time to documenting stories as they unfolded in front of his lens. His acclaimed project Condemned, for example, a study of the treatment of the mentally ill in Africa, was shot over 10 years. But during his numerous trips to the continent, he had become acutely aware of the deep-rooted homophobia there.

“Wherever I went, I was surprised by how extreme the views on homosexuality were,” he says. “While working in Zimbabwe in 2008, I met human rights activists who said that if one of their friends came out of the closet, they would beat him up. In Lesotho, around the same time, I met an environmentalist who would condone violence against gays because it is a sin against God.

“Even in 2014 in, Lagos, a seemingly hospitable man, on hearing that I lived in France, felt it was his duty to explain to me that the state’s economic crisis was due to the legalisation of same-sex marriage. Unfortunately, these are not isolated incidents.”

Nor are they just words. More than 2.8 billion people worldwide live in nations in which homosexuality is criminalised and can lead to imprisonment, beatings and even the death penalty. While working on an assignment for National Geographic in Nigeria in 2014, Hammond heard of five young men who had been arrested there because of their sexual orientation. Convicted of sodomy, they were flogged in court and only narrowly escaped a death sentence.

“I managed to track them down, thanks to a few shared connections, and went to meet them,” says Hammond. “I was really touched by their stories. Though the accounts of the violence they suffered were horrible, I was profoundly affected by the discrimination they faced throughout their lives – especially from their community and family, who had ostracised them. Not only were they emotionally devastated but they also found themselves in a desperate situation with no support.”

He decided to expose the injustice, but finding the right way to do so was a challenge. For starters Hammond has a love-hate relationship with portraiture which, he’s inclined to agree with Jean- François Leroy, can be “lazy photojournalism”, as the Visa pour l’Image director declared at the festival in 2015. The 40-something photographer recalls his early days as a reporter when, shooting assignments for many British newspapers and magazines, he was given only three or four days to cover important and complex issues, often in countries he knew little about. With no time to delve into the issues in-depth, he took the quicker route – photographing the people the journalist was interviewing.

“Those who commissioned me were happy, they had pictures to illustrate their story,” he says. “But I was not. I felt like I was an illustrator when I wanted to be a storyteller. I was rarely contributing anything new, and in some cases I was merely repeating stereotypes.” In his experience, he adds, if you’re taking portraits because you don’t have the time, access or energy to discover truths or provide insights into the story, then the work “can be worse than lazy, it can lack integrity”.

And he’s also suspicious of set-up portraits shot in reportage style, arguing that they disguise what are actually photo opportunities specially arranged for the camera. “Making a picture, even a portrait, seem like it could be unscripted runs the risk of being seen as something that happened serendipitously,” he says. “That, too, is an attack on the integrity of our industry. It cheapens the work of those who have spent hours or days or years working and waiting for events to happen, uninterrupted, in front of them.”

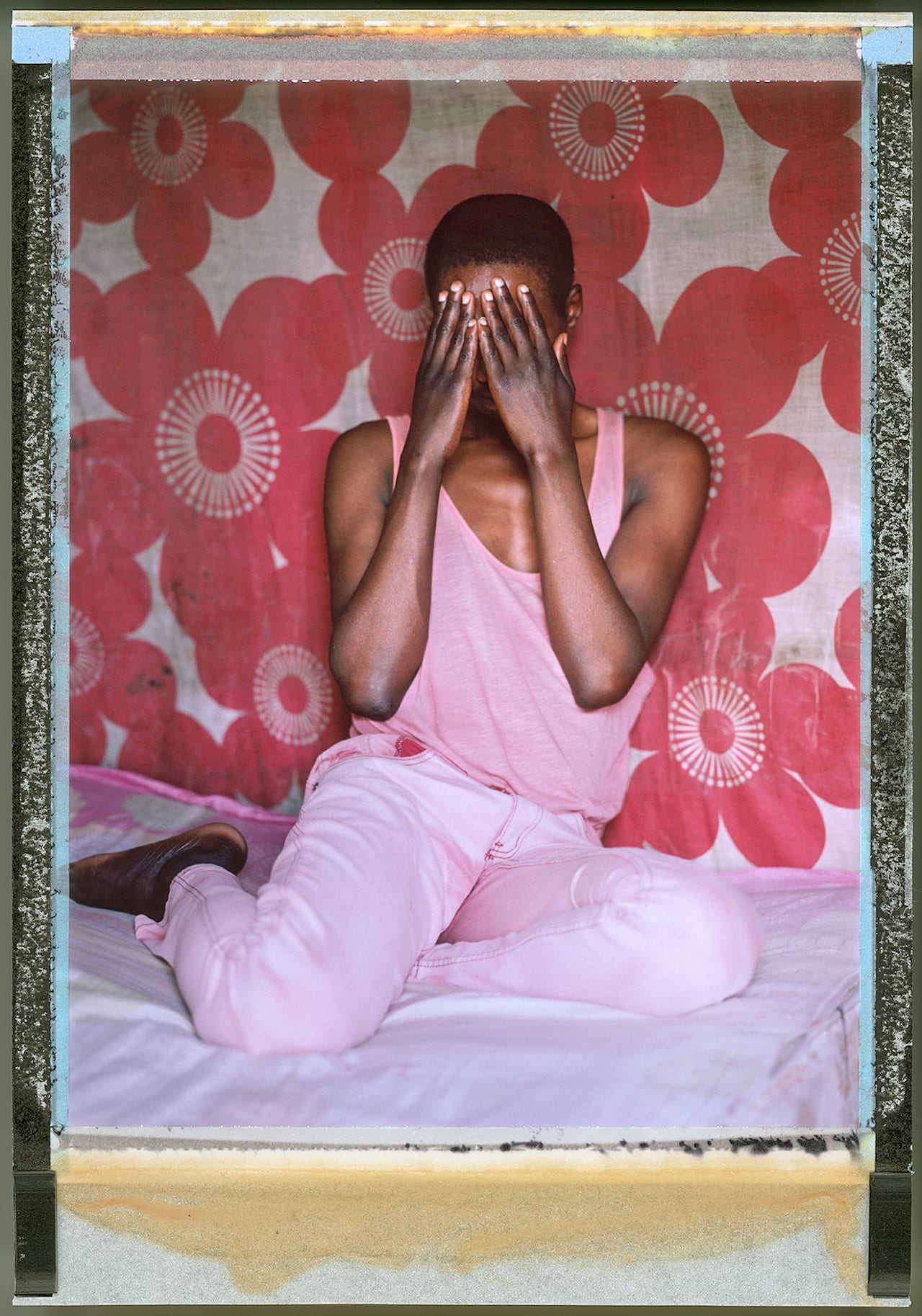

But, for this project, he felt portraits were the only way to go, given that the discrimination LGBTI people face often leaves little visible trace. “Portraits are a great way of making abstract issues, or people who are talked about in abstract ways, real,” he says. And this approach also allowed him to directly involve the sitters, beyond simply consenting to be photographed.

“Some quarters of the LGBTI community told me they were concerned that much of the storytelling was about them, rather than by them,” he says. “With this in mind I set out to make the work a collaboration with those I was photographing, to try and have the work be, in large part, from them.”

He encouraged his subjects to write down their story and presents these narratives, unedited, next to the pictures; he also let the subjects control where and how they would be represented. In this way, he hoped to capture certain truths about them but also about questions of identity, self- representation and perception – themes dear to the LGBTI community.

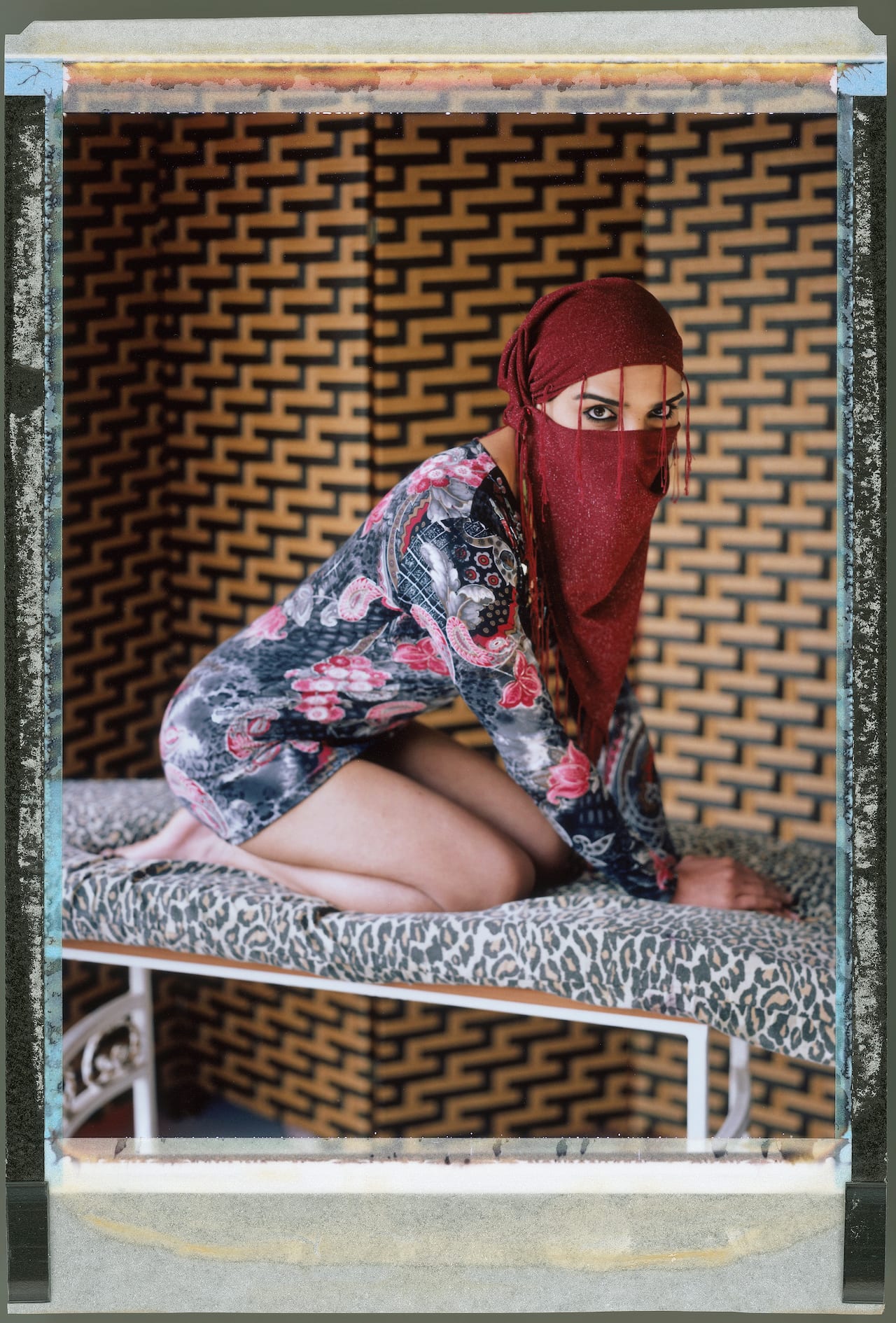

Jessie, a 24-year-old transgender woman, chose to appear shrouded behind a red veil, for example, but her personality still shines through. A Palestinian, born in a Lebanese refugee camp, she surprised Hammond with her cat-like sensuality, just moments after confiding in him that her brother and father had tried to kill her on several occasions because of the “dishonour” she had brought them.

After the shoot, he asked her why she didn’t simply pretend to be a man, given the dangers she faces. She, equally shocked, said she was born a woman and would therefore die one.

“The fact remains that a portrait can never actually fully tell us who a person is,” says Hammond. “But a portrait says ‘I exist’ and ‘I am the one who has been through this’. And, most importantly, a well-made portrait – like any well- made photograph – helps us to connect to people and their situation.”

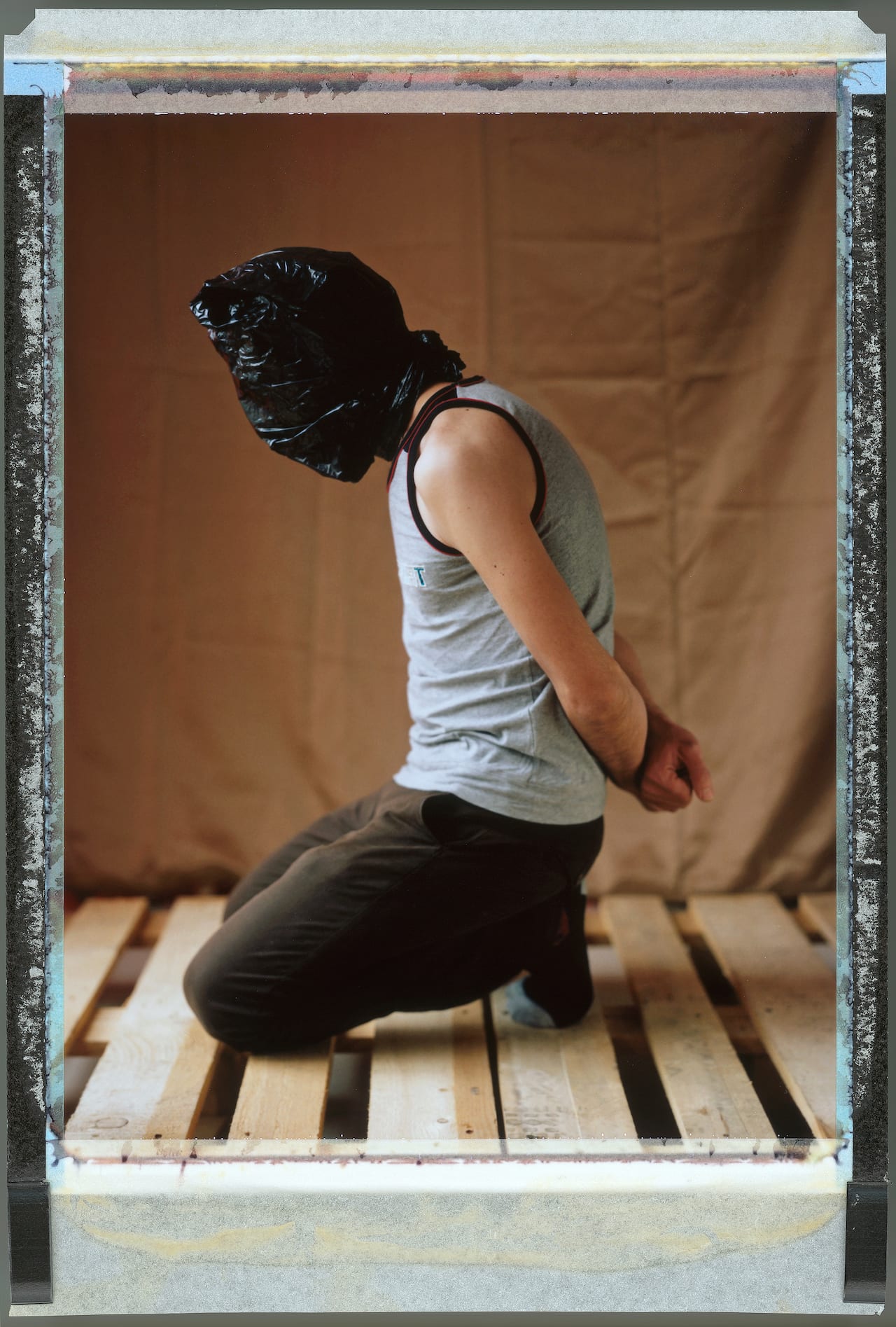

Jessie was not the only sitter who asked to conceal her identity – given the prejudice they face, enshrined in law, many others opted to hide or cover their faces, for their own safety, or to protect their families and friends. “The last thing I wanted was for them to be harmed because they had been identified,” says Hammond.

“I knew some were really afraid. Just locating them had been very difficult. Yet they had stories that really needed to be shared, so, because I really wanted them to participate, I had no choice but to let them have as much control as they needed to feel comfortable with the process. I had to do this on their terms.”

Hammond shot the project on a large format Polaroid camera and, while he initially chose it for aesthetic reasons, it turned out to be a blessing. Creating a unique, tangible print, it gave the sitter the opportunity to destroy the image if he or she felt it would endanger them, in a way that they could really trust; after all, while digital files can be erased, they can also be recovered later on.

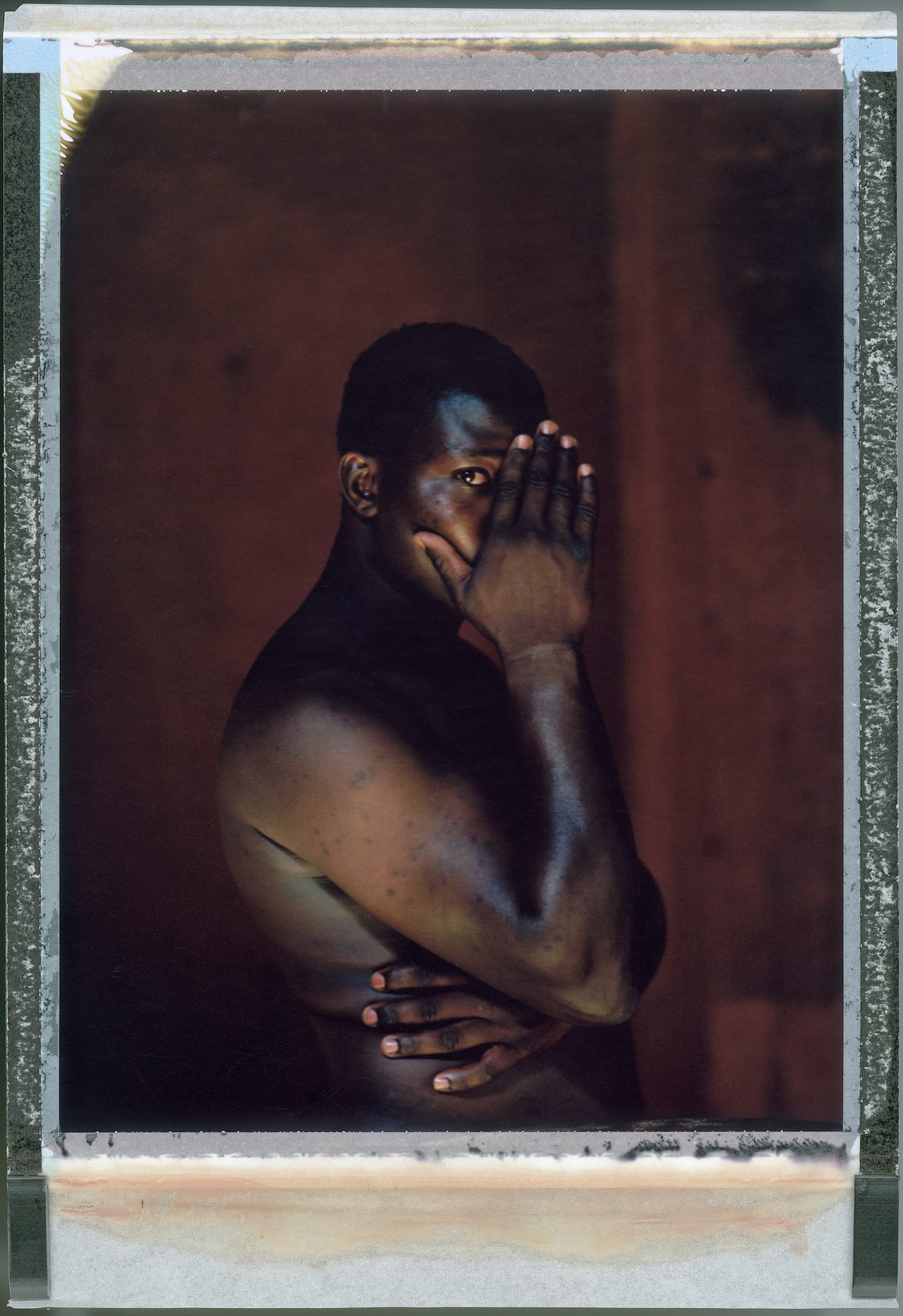

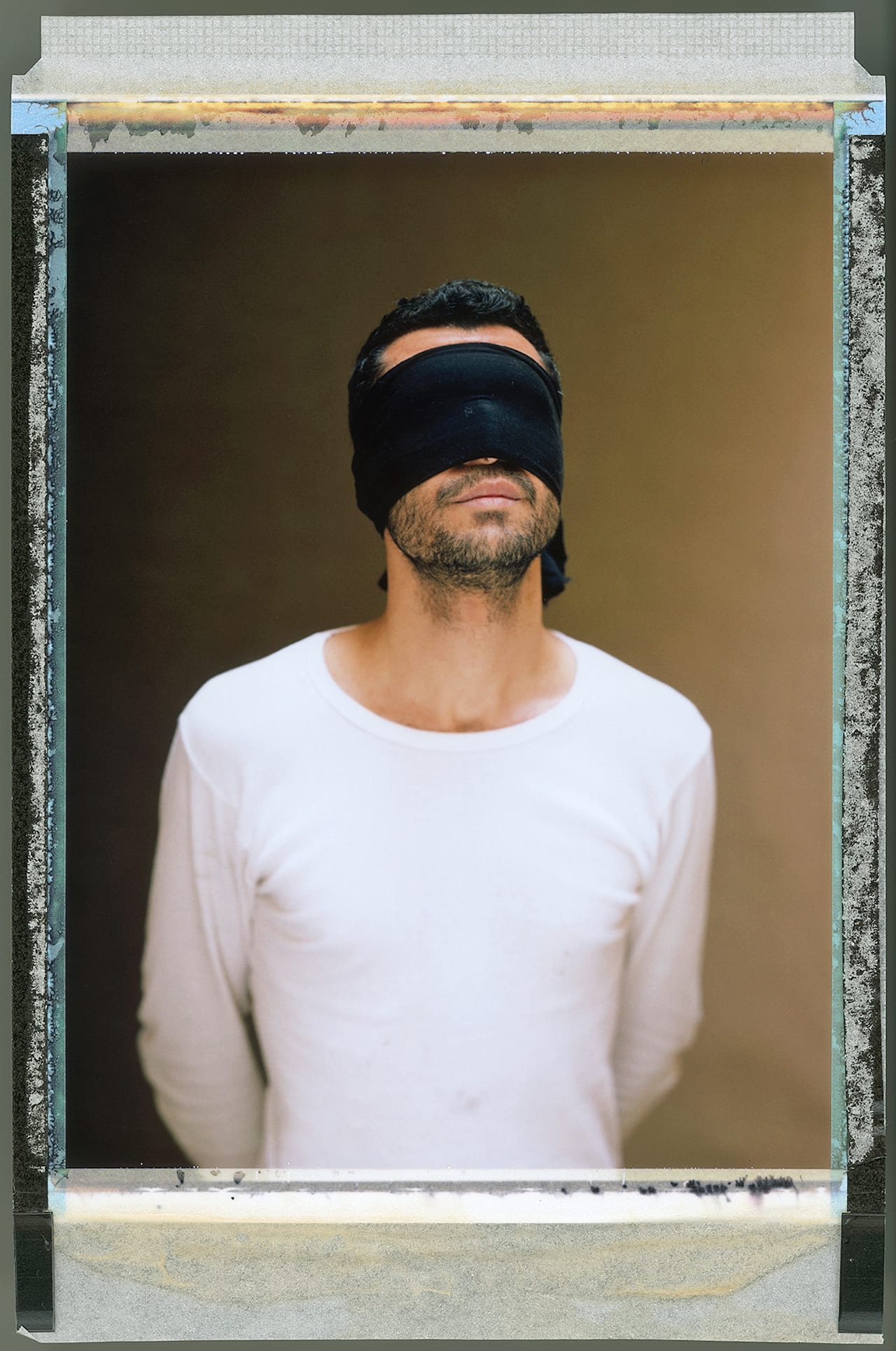

In about a third of the 65 images in Where Love Is Illegal, the subject’s face is obscured, but Hammond argues that they are just as revealing as the full-face shots, and may even show more. By covering the faces, these images are showing another aspect of the sitters’ reality – namely, their fear of retaliation.

Buje, for example, who adopted a pseudonym for the project and peers with one eye from behind his hand, was taken to sharia court in 2013 and held in jail for 40 days where he was beaten with electrical cords. When he confessed to committing homosexual acts, he was lashed 15 times with a horsewhip. He only avoided the death penalty because such sentencing requires the testimony of four witnesses. So while his piercing gaze forces the onlooker to acknowledge him, his hand shelters him and acts a reminder of the danger he’s still in.

“Is a face really who the person is?” ponders Hammond. “Not showing it certainly provides a challenge, as we identify people primarily through their facial features. But do we really know them because of those traits? Perhaps it might tell us about their age, describe something about their culture, or tell us of their emotional state. However, all of these can also be discovered through other elements.”

For example, the love between Ugandan lesbian couple J and Q is no less palpable because their expressions are obscured, nor is the fear that haunts Ratib, a gay Syrian man beaten by the police. The decapitation threats that M faced in Syria are evoked through the knife placed under his chin.

“The covering of Wolfheart’s eyes suggests not only what happened to him but also that ‘his kind’ should not be seen,” comments Hammond. “If we believe that the gaze allows us to connect with one another, the blindfold can be seen as removing his ability to make those connections deemed immoral in that society.

“Some of the most powerful images, in my opinion, do two things. On the one hand, they humanise an issue by having you connect to an individual. On the other, they render them a symbol of the wider situation. The power of the covered face is that it creates just enough anonymity for the sitter to be anyone – even you or me – and speaks of the wider issue. The best photography in my sense is connecting people who wouldn’t otherwise meet. If we do our job right, the barriers of race, distance and culture are broken down.”

To give the project breadth, the Paris-based photographer travelled to seven countries in which the LGBTI community is denied basic rights. He also created an online platform where others from all walks of life, anywhere in the world, can share their stories. Helping raise awareness of the issue and collecting funds to support local NGOs, Hammond hopes the site will create a sense of global community and provide practical aid on the ground. In 2015 he managed to raise enough money to pay bail, legal fees and rent for four Nigerians accused of sodomy, via tens of thousands of followers on Instagram and Facebook.

“Discrimination thrives in environments where those discriminated against are being silenced. Bigoted views are held as truths unless and until they are challenged,” Hammond says. “So it is my responsibility, and the moral obligation of all of us who have the privilege to speak out, to be activists for those who are being muzzled. We, as humans, are responsible for one another.”

www.whereloveisillegal.com Where Love is Illegal is on show at f³ – freiraum für fotografie until 02 September https://fhochdrei.org/ This article was first published in the December 2015 issue of BJP