“I was the first to move to New Brighton, and it was by sheer chance,” says Tom Wood. “I studied fine art part-time [a Fine Art Painting BA at Leicester Polytechnic], then went back to the car factory where I had worked before. Then I found a job as a photo technician at the Poly [now Wirral Metropolitan College, where he went on to teach], and we moved there in September 1978.”

Thus began a golden age for photography in New Brighton, which lasted until 2003 when Wood moved to his current home in North Wales. In the intervening 25 years, Ken Grant also lived in New Brighton from 1992-2002, studying for a spell at Wirral Met, and Martin Parr was based just 20 minutes away from 1982-1985. Between them the three photographers created a huge body of work on the seaside town, which is based just across the River Mersey from Liverpool in North England.

Though they didn’t shoot together, all three photographers knew each other and knew each others’ work, Grant and Wood sometimes showing each other their photographs and Grant studying under Parr at Farnham College, and Wood and Parr exhibiting their New Brighton pictures together at the Open Eye Gallery in Liverpool in 1986. And now work by all three is being brought together in an exhibition in New Brighton, in a sailing school that looks over many of the sights recorded in their images.

“In my mind I knew of all their work and could see all these things in common in their pictures, so I asked Ken when they had last showed it all together, and he said ‘Never!’” says Tracy Marshall, the curator who’s spearheaded the project. “So then I started imagining looking at it all and showing it in New Brighton, and when I mentioned it to Ken he stopped and said ‘That’s a great idea!’”

Marshall was working at Belfast Exposed gallery at the time, but when she moved on to Open Eye, she discovered a strategy in place to make a cultural hub in the wider Wirral area (of which New Brighton is part). Suddenly her idea “escalated to being part of the Liverpool Biennial of Contemporary Art, and part of the cultural strategy for 2018, and everyone was supporting it”, and when she found the sailing school, which is divided into three rooms, it seemed it was meant to be. The resulting show, New Brighton Revisited, will include about 100 photographs, roughly equally divided between the three, plus some ephemera connected to the town and their work.

A popular resort in the early 20th century, New Brighton’s fortunes had already started to fade by the 1960s, when most of the sand on its beaches disappeared because of tidal changes – as Parr pointed out in the introduction to his book The Last Resort (1986). By the time Tom Wood had arrived the pier had just been demolished, and by the 1990s, when Grant arrived, the advent of cheap flights had encouraged British holiday makers to seek out warmer climes. Even so, it’s fair to say that each photographer has seen the town differently and brought out different facets of its life, despite recording the same places, and sometimes even the same faces.

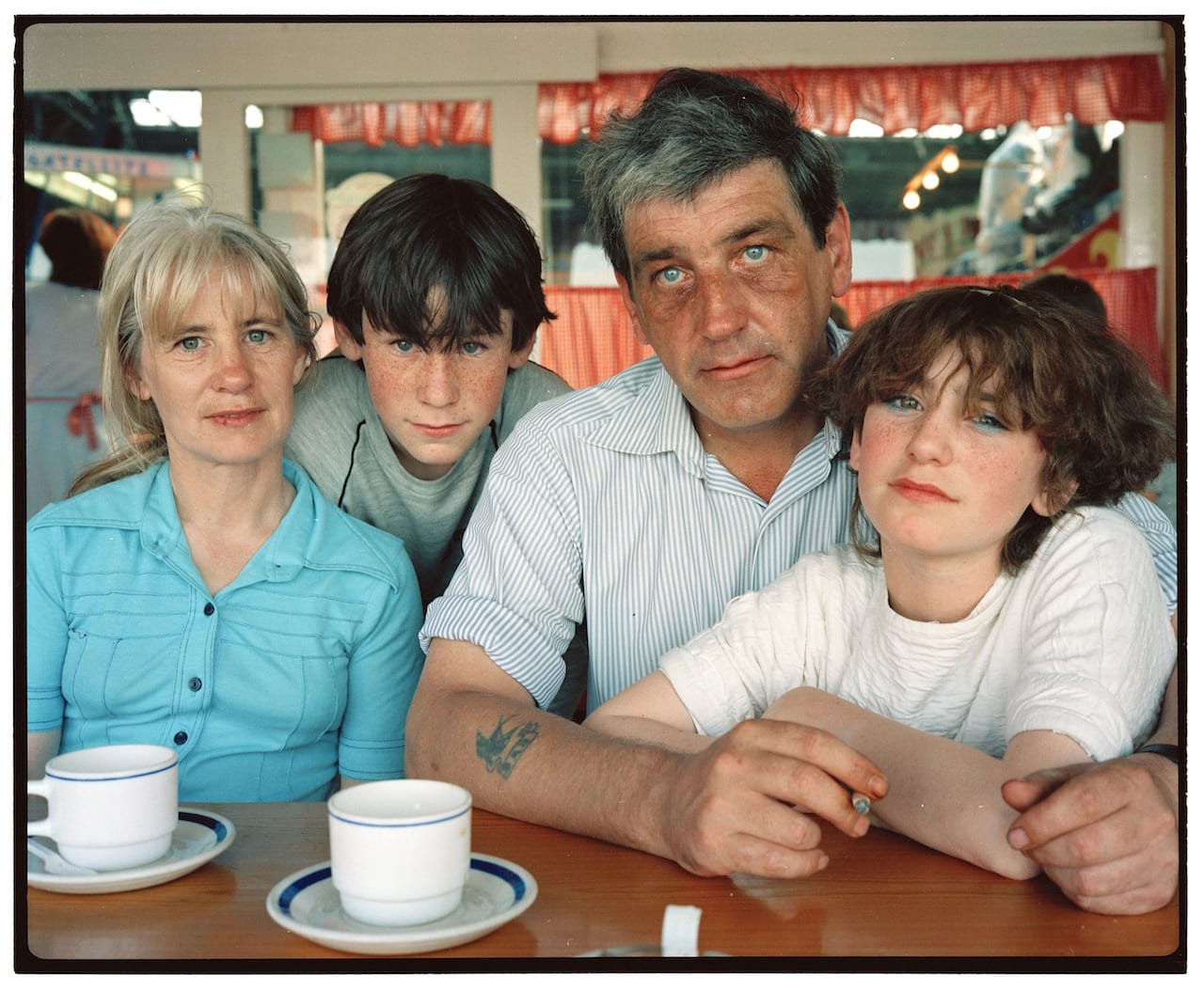

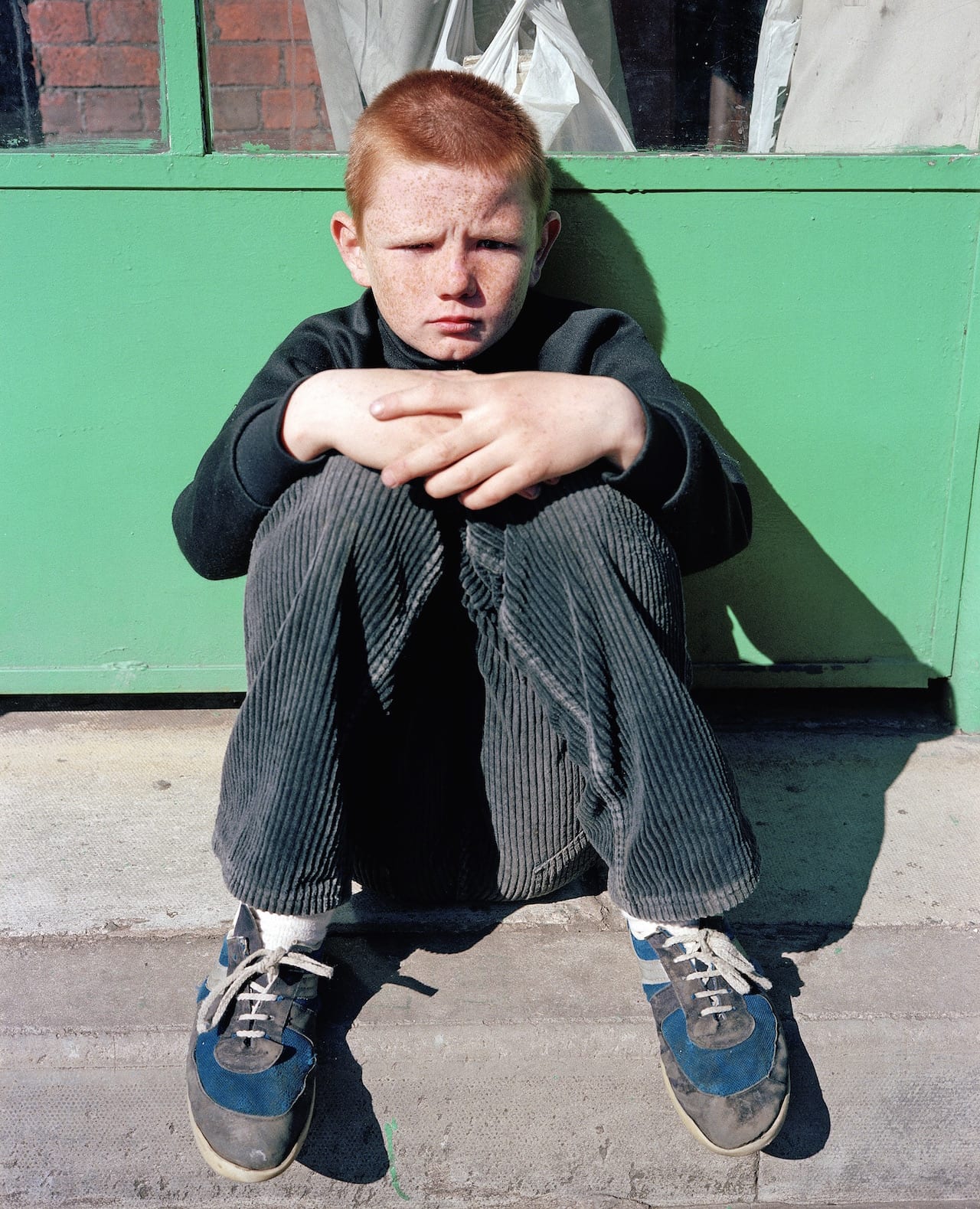

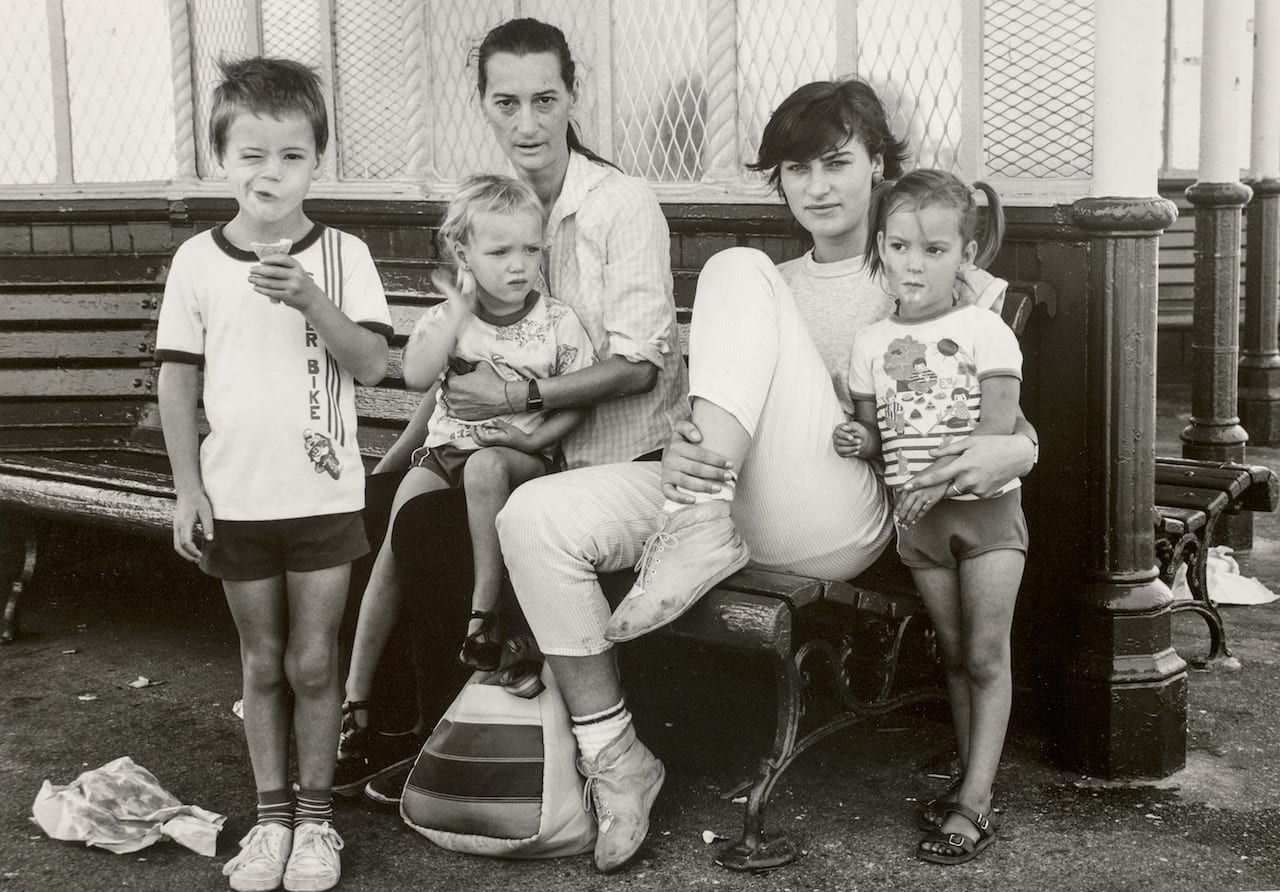

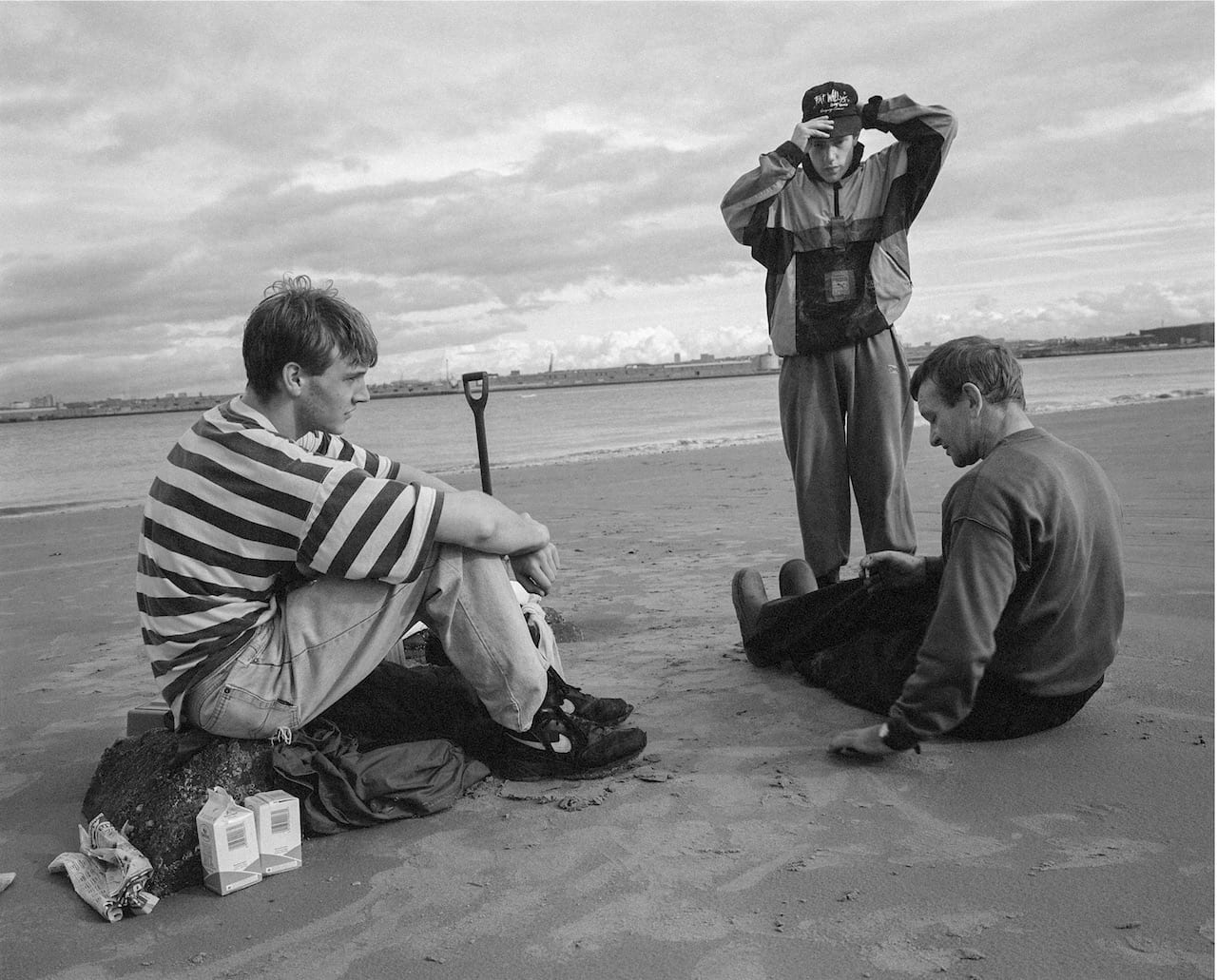

Shot over three seasons, Parr’s images focus on the gritty chaos of hot weekends and Bank Holidays in a seaside resort; Grant’s, by contrast, often show quieter moments of everyday life. Wood’s lie somewhere in between – they can be “unflinching, there’s something quite tough about the way he sees things,” as Grant puts it, “but he still has a sensitivity towards people”.

It’s a difference born of different personalities, and of very different ways of working. Parr’s work was focused, shot over three summers and, shortly after the show with Wood, published as a book, the seminal The Last Resort (1986). Grant’s and Wood’s were shot over years, with no specific project in mind. Wood published his first book, Looking for Love, in 1989, Grant hasn’t published a book of images of New Brighton specifically, but he published his first book of Liverpool work, The Close Season, in 2002.

Wood and Grant also shot people they knew, at least by sight, by virtue of having lived in the neighbourhood for so long; Wood shot compulsively, all the time – when he went on the bus, while he waited for the ferry, and when he went to the football or to the market. Much of his work has still not been printed, and it would take six months just to go through all the negatives, he says; he also has 700 hours of video.

“I take pictures all the time, if did a project, had a plan, it would be self-conscious,” he says. “It’s very different to go out looking for something. All that stuff can get in the way, whereas if you take pictures all the time, it’s no big deal because that’s what you do all the time. And because I was always doing pictures, going to the same places year after year, I became part of the scenery. I was just the guy who takes pictures.”

And though Grant worked in a similar way, his images are different again because of his relationship with New Brighton – born in Toxteth, a deprived inner-city Liverpool district, he grew up near the town, unlike Parr (who was born in Surrey) or Wood (who’s from Ireland). He went on day trips to New Brighton as a child, and then again, in a different way, as a teen, he says; after leaving school he worked as a carpenter and lived in a “rough” area in Liverpool so, when he got the chance to move to New Brighton, after winning a grant to pursue his photography, he had a sense of moving to “the edge of the world”.

“Martin was preoccupied with the untidiness and business and immediacy of the place, for me, New Brighton has a sense of respite,” says Grant. “I have a lot of very quiet pictures, pictures of people by the coast. I was photographing lots of people my age and older, hanging out and killing time. I grew up not too far away, and we would go there because it’s the kind of place where you can kill a day.

“It’s not a defined project but it’s really specific in a way – I see it differently because I grew up there,” he adds. “I’m not sure it’s a good thing though – my photographs of it can sometimes be sentimental,” he adds. “Some pictures I really like, but I know they’re maybe too sweet.”

And for Marshall, Grant’s images also have a different quality because he is different person to both Parr and Wood, with a different manner with people. “Tom is very loved [in New Brighton], he’s the ‘Photieman’,” she says, referencing the nickname Wood picked up from the kids in the local area. “Ken’s so quiet that it’s only when the pictures come out that people realise they know him.”

And the three photographers’ images are different in other ways too, most obviously in the way they’re shot. Grant is showing finely toned black-and-white images in New Brighton Revisited; Parr is showing some of the iconic images from The Last Resort, which set the tone for his whole career – and arguably changed the course of British documentary photography – by using saturated colour and a flash.

But Parr is also showing some of his earlier black-and-white photographs – images in which, says Marshall, “you can see his confidence grow as he gets older and goes much closer to faces”. “They’re early pictures, taken before I did colour,” says Parr. “I wanted to show them because they’re not so well known, but also because I like them. There are only ten [in the exhibition] but they work.”

Wood’s photographs are also (mostly) colour, but he uses a distinctive pastel palette which, perhaps, helps add the softness to his “toughness”. He says it’s partly inspired by the photographs he saw when he was starting out, which – because it was the 1970s and both photobooks and photography exhibitions were scarce – were snapshots and postcards rather than documentary photography, printed in colour but faded with time.

“They influenced me far more than anything else,” he says. “So for me it had to be colour, but no one used colour, and colour was expensive. So I was using outdated film because it was cheaper – outdated film and cine film, which I used to cut into sections myself. It was 10p per roll, and if you cut your own you’d have 20 in an hour.

“That also meant my photographs looked a certain way, but I wanted to keep my costs low so I could work freely,” he adds. “I never wanted to sell pictures to get commissions, I hated that sort of documentary story. The documentary photographs people seemed to love seemed to be arrive, spend a few days, get 10 pictures. I believed pictures should be useless. I did a bit of part-time teaching so I’d have that freedom to just do the work.”

And, maybe because of this softness, Wood’s images are liked by the people they depict – even when they’re shown out partying and ‘looking for love’ in the Chelsea Reach, then the local nighttime hotspot. His book Looking for Love was in every hairdresser’s in the area, he says, and the only negative comment he got was “remind me not to kiss in public”. When he showed an exhibition called The Pier Head at Open Eye in 2018, 1000 people came to the opening. “They were, like, queueing to get in,” he says.

“There were people there I haven’t seen in 20, 30 years,” he continues. “There were people there who knew people in my pictures who had died – the girl next to the girl with the pink lipstick in Looking for Love, she died and they have that picture framed on the wall. That personal interest is another thing. It was very emotional.”

Parr’s photographs, by contrast, have been more controversial. The Last Resort was heavily criticised for its perceived satire when it was shown in London’s Serpentine Gallery in 1986 and, says Parr, that sense of slight then filtered back to New Brighton. “The local reaction was muted originally, it was only when it came to London and the intelligentsia started up,” he says. “The people in Liverpool knew that that was what it was like.”

Whatever the cause the grievance was real and lasting, causing “a big divide and controversy in the community,” says Marshall. “Even the words ‘Last Resort’ were forbidden after the book – it’s the end of the Bank Holiday, all that litter,” she adds. “I was very conscious not to put too many litter ones in, I wanted to respect the fact that the town had let me in.

“Opinion is definitely divided. There’s a young audience who can see it could be good for the area. But you do have people who say he defeated our town and for the last 20 years we have never bounced back. Everything is blamed on Martin, fairly or not.”

And Marshall’s words raise another moot point, which is what staging this show in New Brighton could mean for the town and its people. First off, there’s the chance to for the locals to see how they and their home has been depicted – though Wood gave many prints away at the time, and his and Parr’s books are already known.

Secondly there’s the wider aim which helped Marshall get support for the project – the attempt to regenerate the area through the arts. Including this big show, with such big names, within the Biennial is part of that process, the hope being that people from the arts and photography who come for the festival will therefore make the trip out to New Brighton, rather than just staying in Liverpool. And using the sailing school as a venue could help the town in a more immediate way too – this show is its first outing as a cultural venue, but the hope is that more could follow.

But third, there’s the fact of putting the images back into the context in which they were shot – in a venue with windows on all sides, which look out at the locations of some of the photographs. In this, perhaps, this exhibition honours both New Brighton and its people. “The colour pictures of the amusement arcade – it all looks exactly the same,” says Marshall. “It’s like the town itself is another artist in the show.”

“They’re very different bodies of work,” says Parr. “But something runs through them all.”

New Brighton Revisited is open from 14 July – 25 August at The Sailing School, Marine Point, New Brighton www.northernnarratives.org