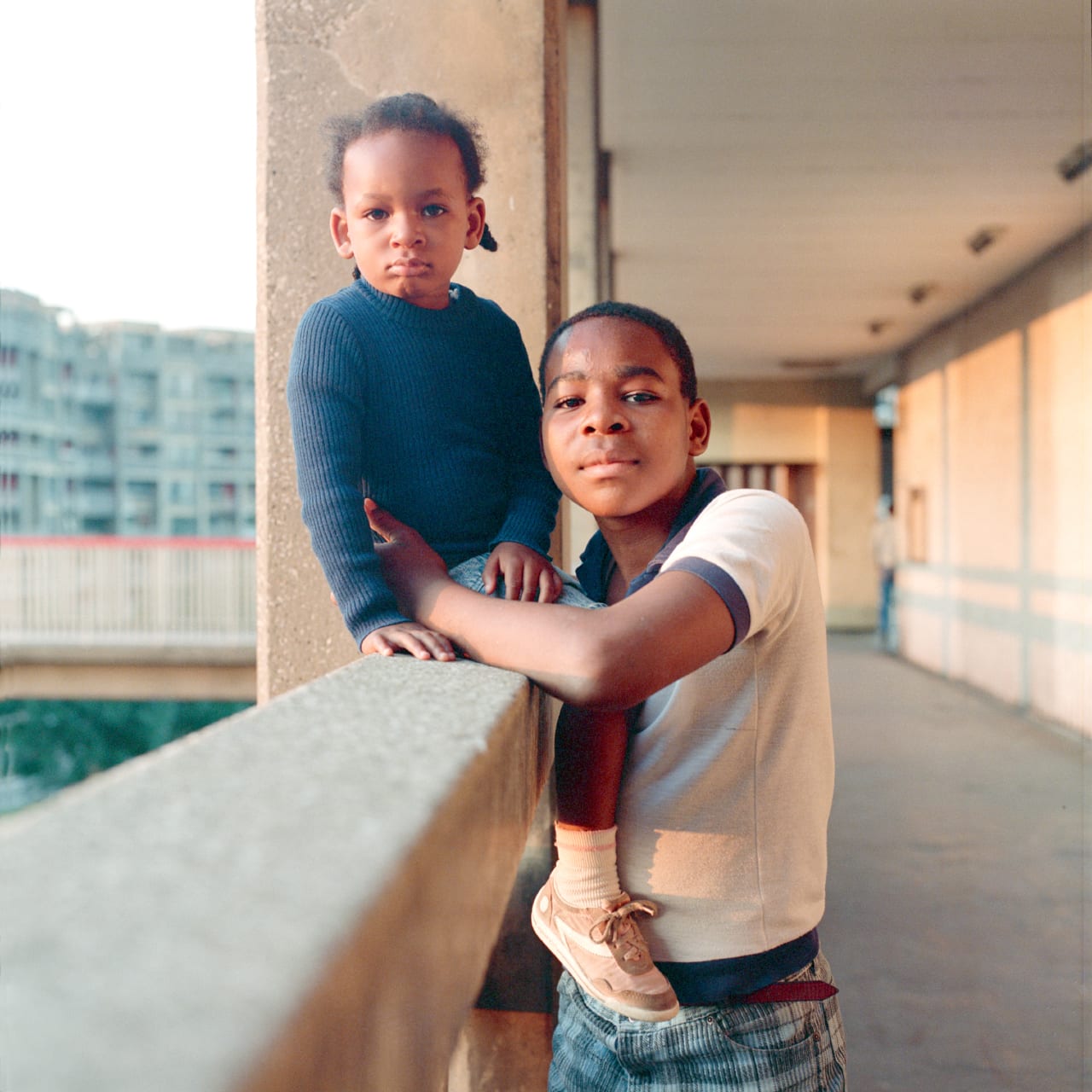

“None of the people I met wanted to move, they were happy there,” says Bill Stephenson, who photographed the last residents of Hyde Park Flats, Sheffield before it was demolished 30 years ago. “The tenants felt like they were being pushed around, they didn’t know where they were going. The brutalist architecture of the Hyde Park flats had become a special place to live”.

Set on one of Sheffield’s seven hills, the four high-rise flats were once part of Park Hill Estate, at the time the largest social housing estate of its kind in Europe. Built between 1957 and 1961, Park Hill had a deck access scheme considered revolutionary at the time, which provided walkways wide enough for small vehicles like milk cart, and earned the estate the nickname “streets in the sky”.

In 1998, just ten years after the Hyde Park flats were demolished, Park Hill was given a Grade II* listed building status, making it the largest listed structure in Europe. Now, the remaining estate is undergoing refurbishment, and the flats are high in demand for their views across the city and easy access into town. Should Hyde Park have been left standing, the whole estate would probably now be protected.

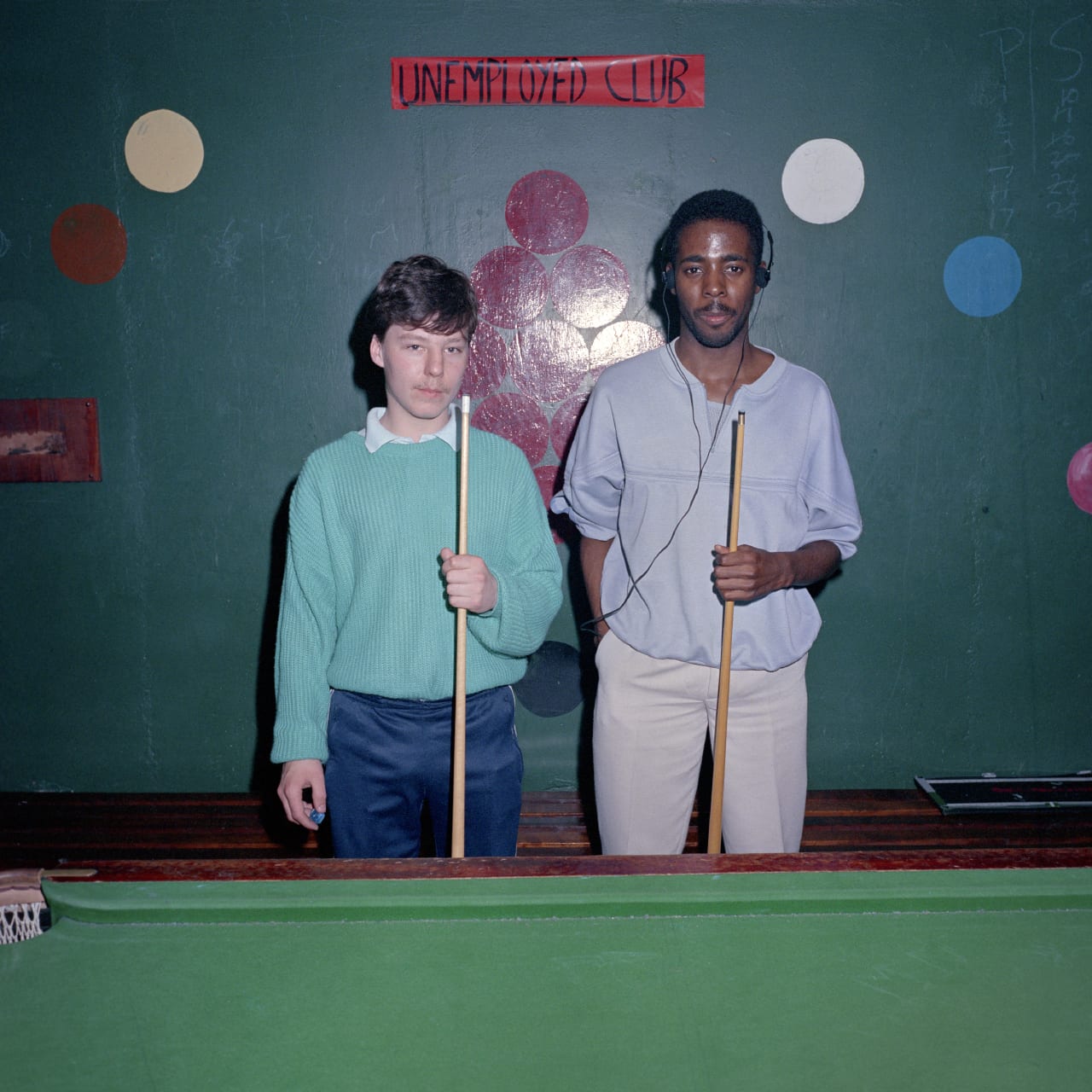

This month a new gallery, S1 Artspace, opens in Park Hill Estate with an inaugural exhibition titled Love Among the Ruins. The show is a re-interpretation of Streets in the Sky, a 1988 exhibition of Stephenson’s portraits of the last residents of Hyde Park, plus Roger Mayne’s documentation of the estate in the 1960s. The new show will exhibit selected photographs by Stephenson and Mayne, along with archival material and a short film about Park Hill produced by the BBC in 1965, The Fortress.

Hyde Park was only 22 years old when the council deemed it a failed social experiment, but Stephenson suspects that it had deliberately started to run it down years before by, for example, refusing to do maintenance work. “There was this much broader picture of the politics that was going on during the 1980s,” he explains.

“There was a period of social engineering where tenants were being moved from social housing into the private sector. We were suspicious that it was an abnegation of social responsibility by the Thatcherite government.”

The work sits within a canon of Stephenson’s previous projects, documenting working class communities which no longer exist such as the Dial House Working Mens Club in 1983. “It shocks me how fast things can move,” he says, “how quickly photographs can go from being contemporary to historic images.”

Stephenson’s career in documentary photography started with a season as a photographer at Butlins holiday camp in 1977 – an experience not for the faint-hearted but which, in retrospect, was the making of him. “Looking back that was a defining part of my career,” he says.

“Being verbally abused constantly by drunk revellers did me a great favour, it gave me a huge amount of confidence in photographing people in crowded places.”

Stephenson also owes something to BJP, which published a portfolio of his work in 1978. This exposure lead to an invitation from lecturer Ken Phillips to study on the Fine Art course at Sheffield City Polytechnic, which helped set him on the career he’s still following today.

Before Hyde Park was demolished, Stephenson spent eight months wandering around the estate, concealing his Hasselblad camera in a sturdy carrier bag to avoid looking intimidating or too official. “I’d buy a can of pop and some cigarettes, talk to people and get introductions,” he says.

“Accessibility is the key to most good documentary photography. If you can relate to people and show an interest in them you get far better pictures.”

Stephenson recalls people coming up to him with photographs of sunsets they’d had taken from the top of the estate. “People were proud to live up there,” he says – and he adds that, while public opinion was was split on whether the estate was a treasure or an eyesore, he can vouch for the phenomenal views.

“I personally loved it,” he says. “I loved the concrete, and the incredible post-war optimism that built it in the first place. But the thing I loved most was that it was social housing. It was for working people, it wasn’t meant to be for private ownership.”

At the time, Stephenson and the estate’s residents thought the decision to demolish it was unfair and short sighted. “When I started the project, if I’d heard people saying they wanted to leave, the photographs would have reflected that,” he says.

After the demolition, residents were dispersed into various run-down council estates in the outskirts of the city. But there is still a community of over 800 ex-residents on Facebook, who have been invited to the gallery to share their photographs of the estate. Their work will be scanned and stored in an archive, but for now Stephenson’s images remain a testament to the closely-knit community he got to know so well.

“One element I wanted to bring across was racial integration amongst the tenants,” he says. “At the time there was a lot of bad press, but that wasn’t the case there. People got along very well together, I hope that intimacy is reflected in the pictures.”

https://billstephenson.co.uk/ Love Among the Ruins will run from 20 July – 15 September at S1 Artspace, Sheffield www.s1artspace.org