“South Africa is a deeply religious country,” says Giya Makondo-Wills, whose work-in-progress, They Came From the Water While the World Watched, maps out the interplay between Christianity and ancestral religion in the region. With four trips to the country under her belt so far, the 23-year old has travelled as much into the past as in the present, tracing the indelible repercussions of 19th-century European migration as they resonate through South African culture today.

Makondo-Wills, who is British-South African, became interested in her African grandmother’s faith while shooting another project. “She’s very Orthodox Christian but she also still practises ancestral religion, and that’s a core part of who she is. She prays to a God and the gods,” the photographer explains.

This duality got her thinking about the intersections of belief systems and how they were brought into contact. How did Christianity become so influential? How does it co-exist with indigenous religions? Building on her interests in race and identity, these questions soon elicited many others, spawning a long-term project that has carried her from a BA to an MA at the University of South Wales.

As her research unfolded, the role that missionary activity played in colonisation, used as a tool to dismantle indigenous culture, anchored the project in a complex, entangled – and personal – history. “I’m looking at it from the perspective that one half of my family have been severely affected by colonisation, institutionalised racism living under the apartheid regime and white supremacy,” Makondo-Wills says. “Then the British part of my family have, historically speaking, been complicit in that.”

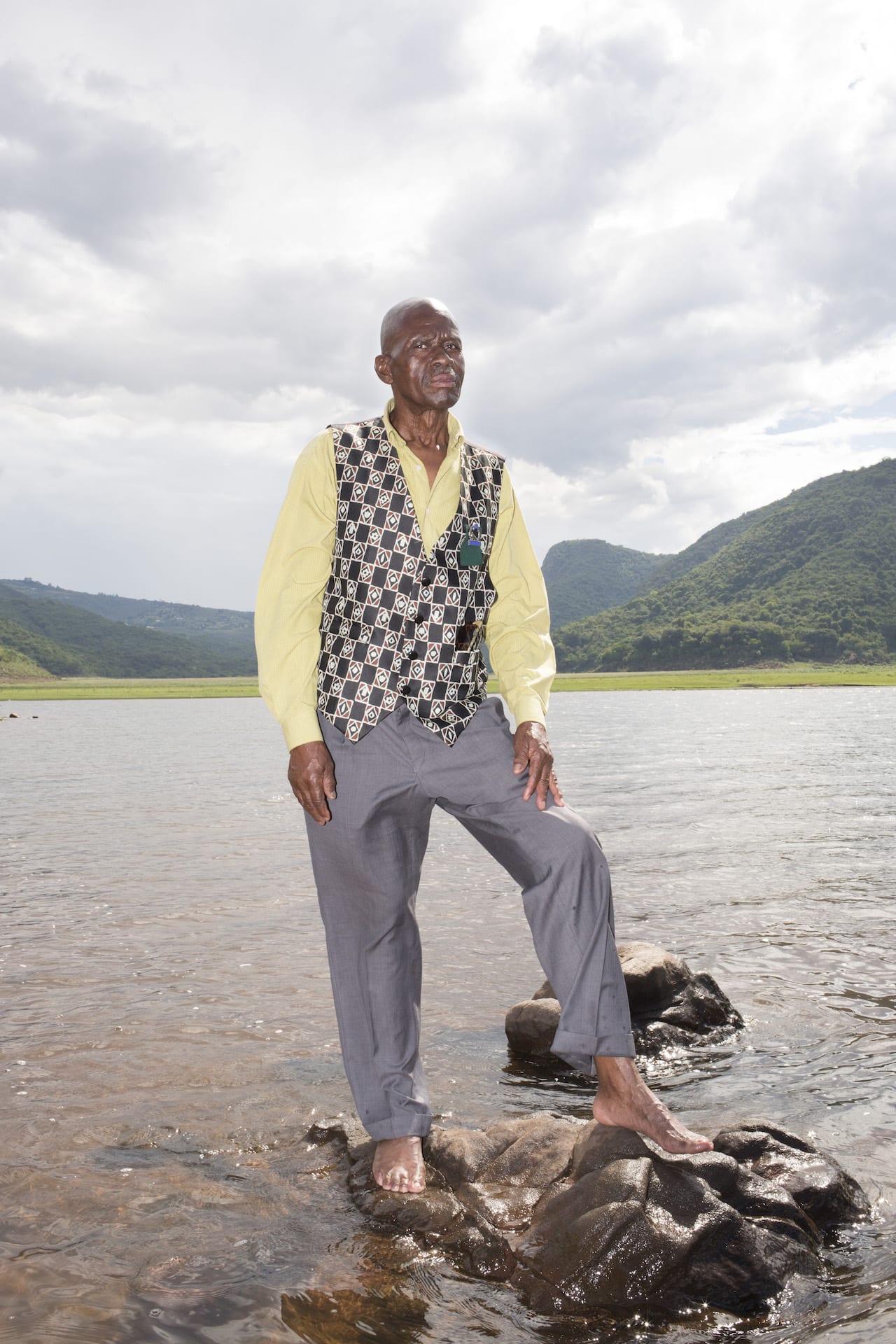

One of the outcomes of this dual perspective is that They Came From the Water While the World Watched both celebrates the many facets of contemporary faith while also framing them within the insidious histories of colonialism. From photographing traditional healers and medicines to missionary practices, the landscape that Makondo-Wills captures pays testimony to the resilience of pre-colonial cultures and charts their evolution.

“A good example of the combination of ancestral religion and Christianity was a traditional healer who had [remedial] products in his workspace, but also a Bible and a cross,” she says. “He was using both so fluidly. Because really they are similar; it’s about faith, healing and looking to something bigger than yourself to help you.”

The next step is to include archival material from UK-based collections, such as the London Missionary Society and the British Empire & Commonwealth Collection. In opposition to photography’s use as a tool of oppression to consolidate the colonial narrative, Makondo-Wills’ pictures build a new form of ‘evidence’, one of resilience and diversity that tells the story in all its complexity.

Ultimately, it’s this educational potential that she hopes to draw out from the project. Describing herself as lucky to have been brought up in a politically-aware household, she says: “I didn’t get that education at school, the historical education which would have been relevant to me and my heritage. So I’m really interested in that and how it affects young people today.”

giyamakondo-wills.com Giya Makondo-Wills’ work is included in Hiraeth, the University of South Wales’ MA Documentary Photography 2018 graduate show from 05-07 October at Old Truman Brewery, Brick Lane, London E1 6QR. This article first appeared in the August 2018 issue of BJP www.thebjpshop.com