Before becoming a photographer, Sean Hillen was a tinkerer. As a young teenager, one of his favourite pastimes was to take apart his grandfather’s old cameras and then piece them back together again. It wasn’t long before he discovered that he could rewind a brand new 120 roll of film into an outmoded 620 camera. “I did that, I got them developed, and I was immediately addicted to photography”.

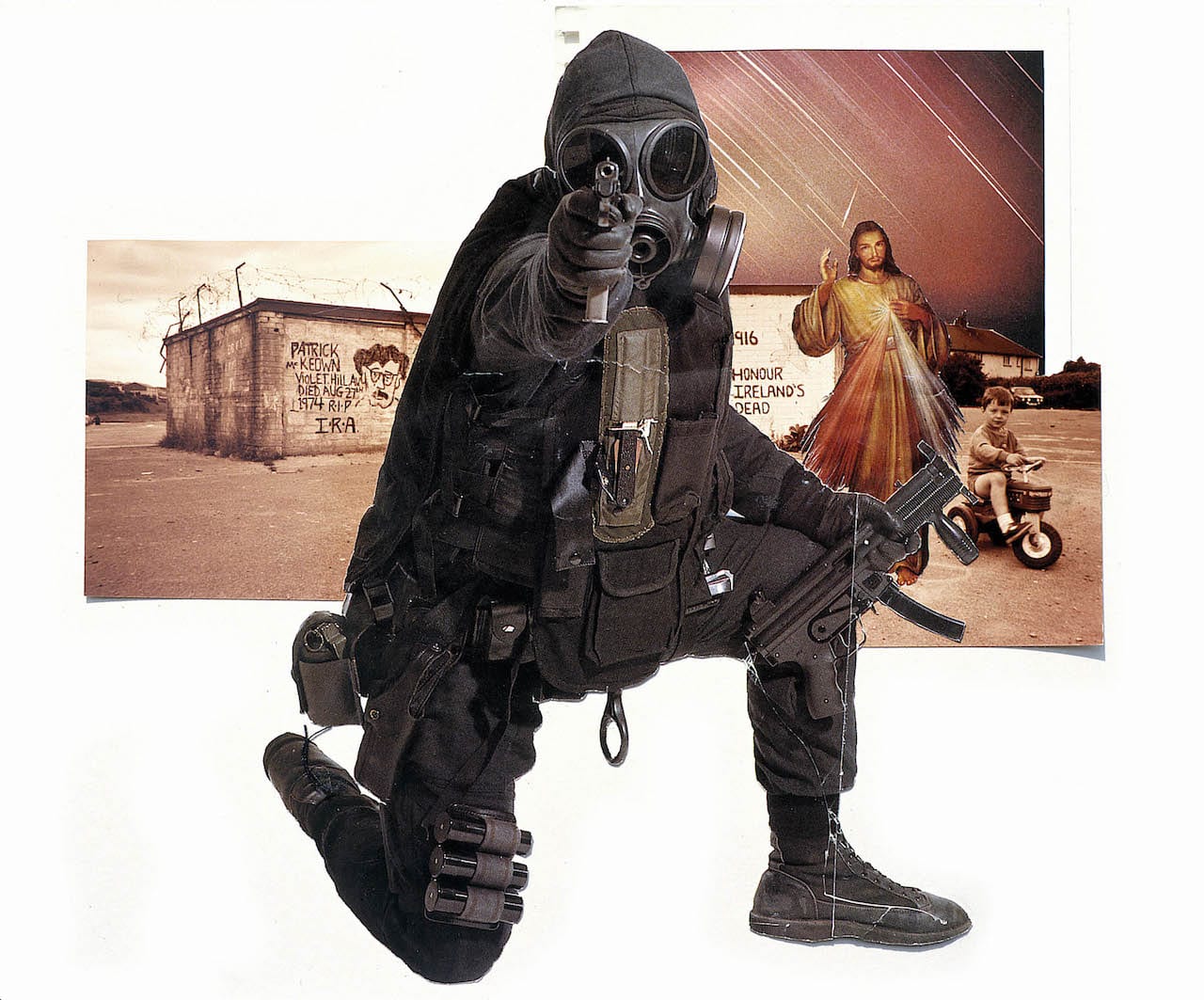

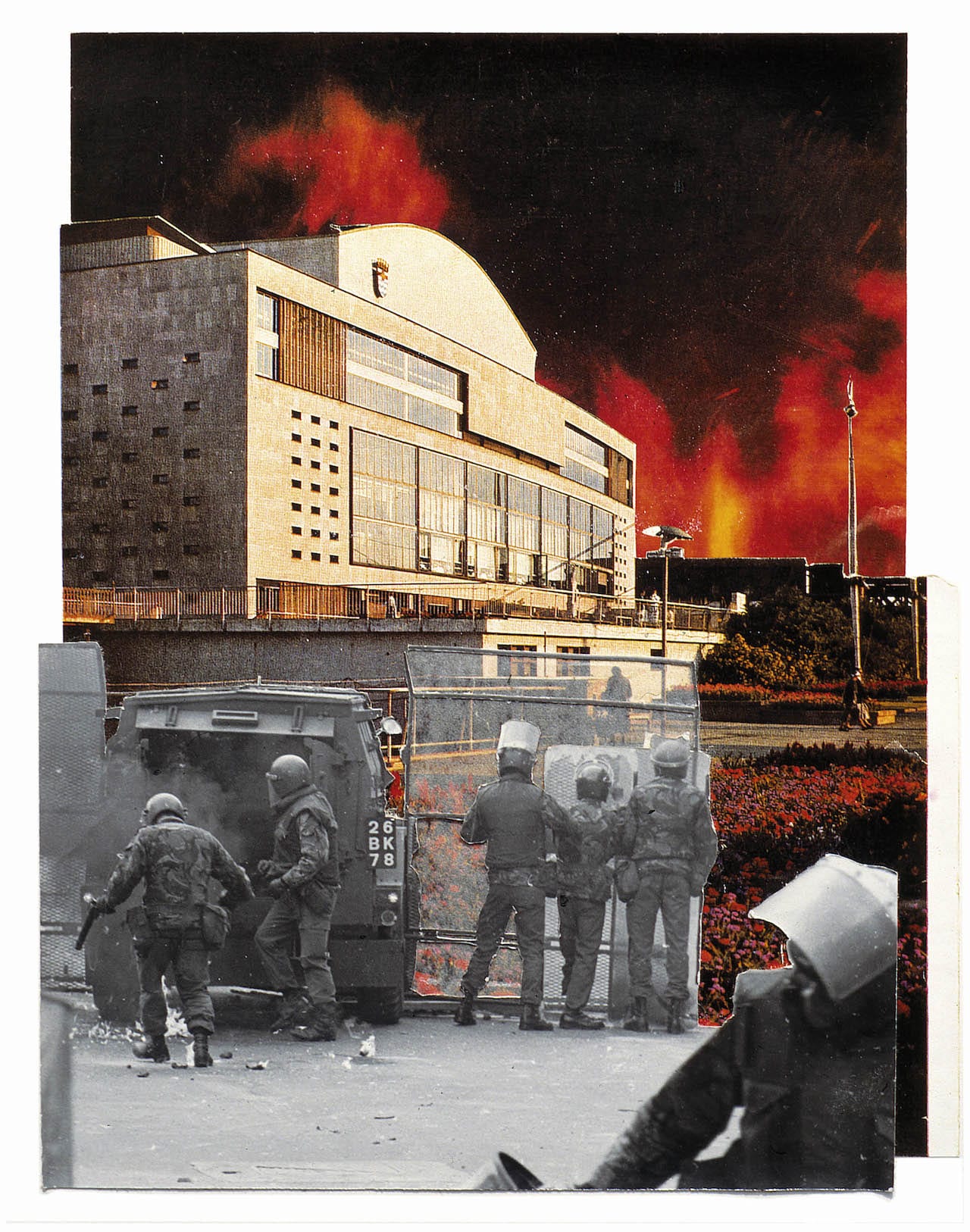

Hillen grew up through the Troubles in Newry, Northern Ireland, close to the border with the Republic of Ireland. “It was utter chaos,” he says. “I knew people who got killed, and I knew people who killed other people”. Hillen and his four siblings would lie awake in bed at night listening to gun battles, which were so frequent that they were able to distinguish between the sounds of different weapons.

After being arrested for stone-throwing as a teenager, Hillen’s parents decided to invest in his photography, hoping it would keep him from being drawn into the conflict like so many of his contemporaries. His father, who was a tinkerer too, had built a model railway in the attic of their home, cobbled together from secondhand parts. He let Hillen convert the space into a darkroom, where he “must have spent years of [his] life”. Though they never had much money, his parents bought him his first camera on credit from a mail order catalogue, a Zenit-E, which cost £52 at the time.

At the beginning photography was “just something to do” for Hillen, who would run around town taking pictures of buildings and landscapes, and making portraits of his friends at school. But at 17, while taking advanced physics and maths at grammar school with the hope of becoming an architect or an engineer, a painter came in to talk about art school – a path he had never known existed.

Inspired, Hillen moved to London in 1982 to study at the London College of Printing [now the London College of Communication] and then the Slade. But being away from Ireland and among “beautiful arty people in London” didn’t mean he was removed from the violence back home. While at the Slade, Hillen found out that his best friend had killed himself while building a bomb in his sister’s back room. Hearing this tragic news, and all the awful press coming from home, Hillen felt he had to return to document it.

“I couldn’t resist it,” he says, “I’m lucky, in a way, that I had such a horrible time, and lucky that I grew up in this cesspit of a war. I wouldn’t wish it on anybody but it made me an artist”.

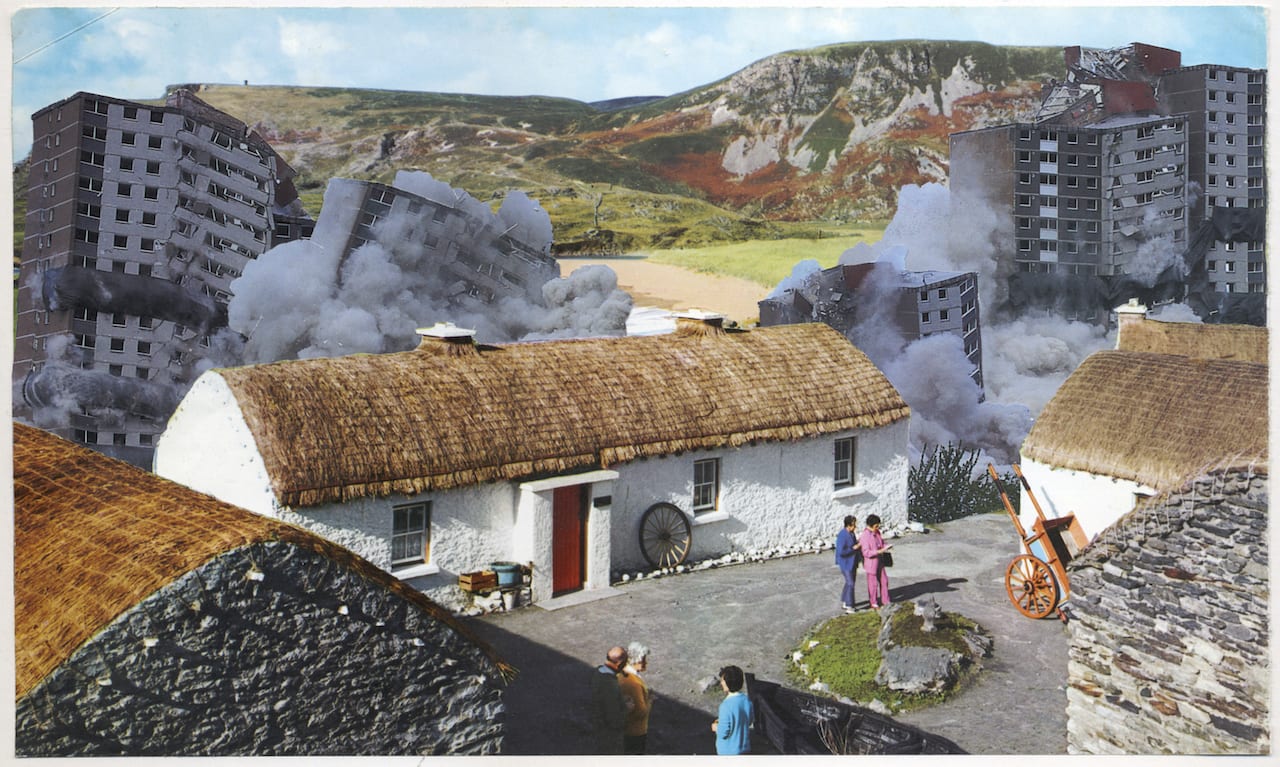

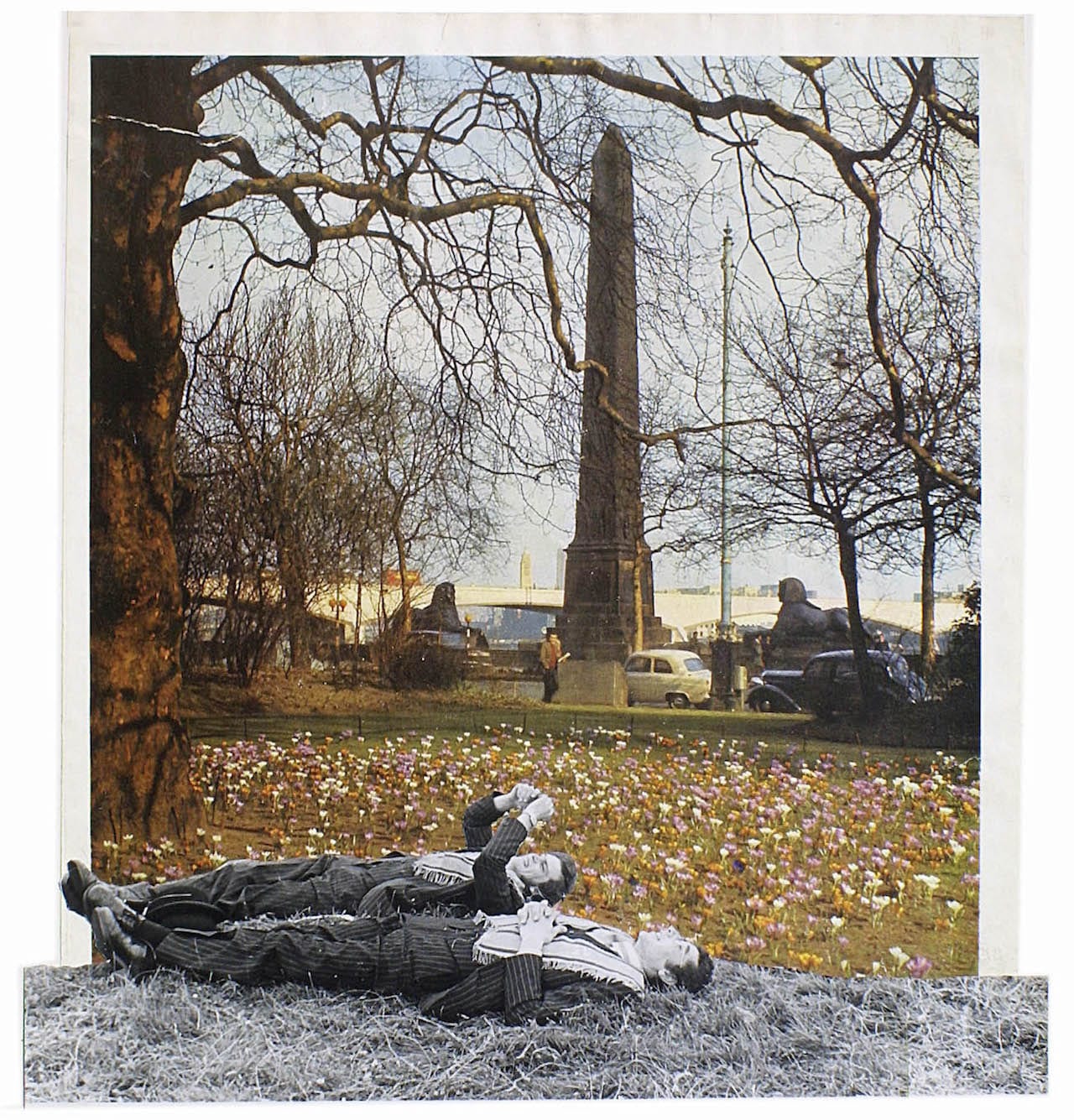

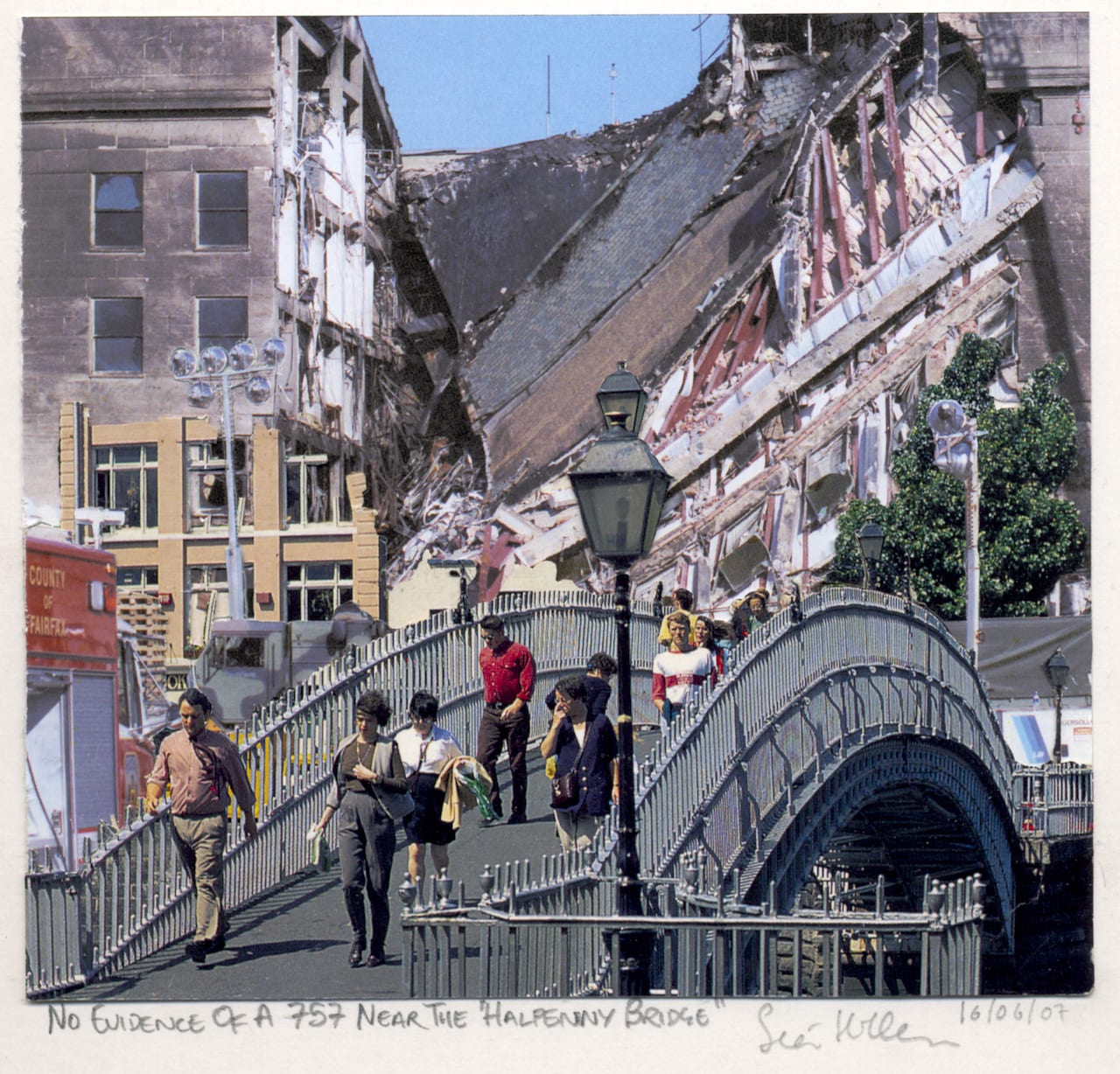

Back in London again, Hillen realised that the papers were already saturated with photographs from the Troubles, and that he wasn’t satisfied with his own. So his prints went under the knife, and slowly, he began to hoard what would eventually become boxes and boxes full of bits of paper and cardboard. He would collect pages ripped out of magazines and newspapers, stacks of postcards bought in London’s tourist shops, toy packaging imported from China, and religious imagery collected from various newsagents around town.

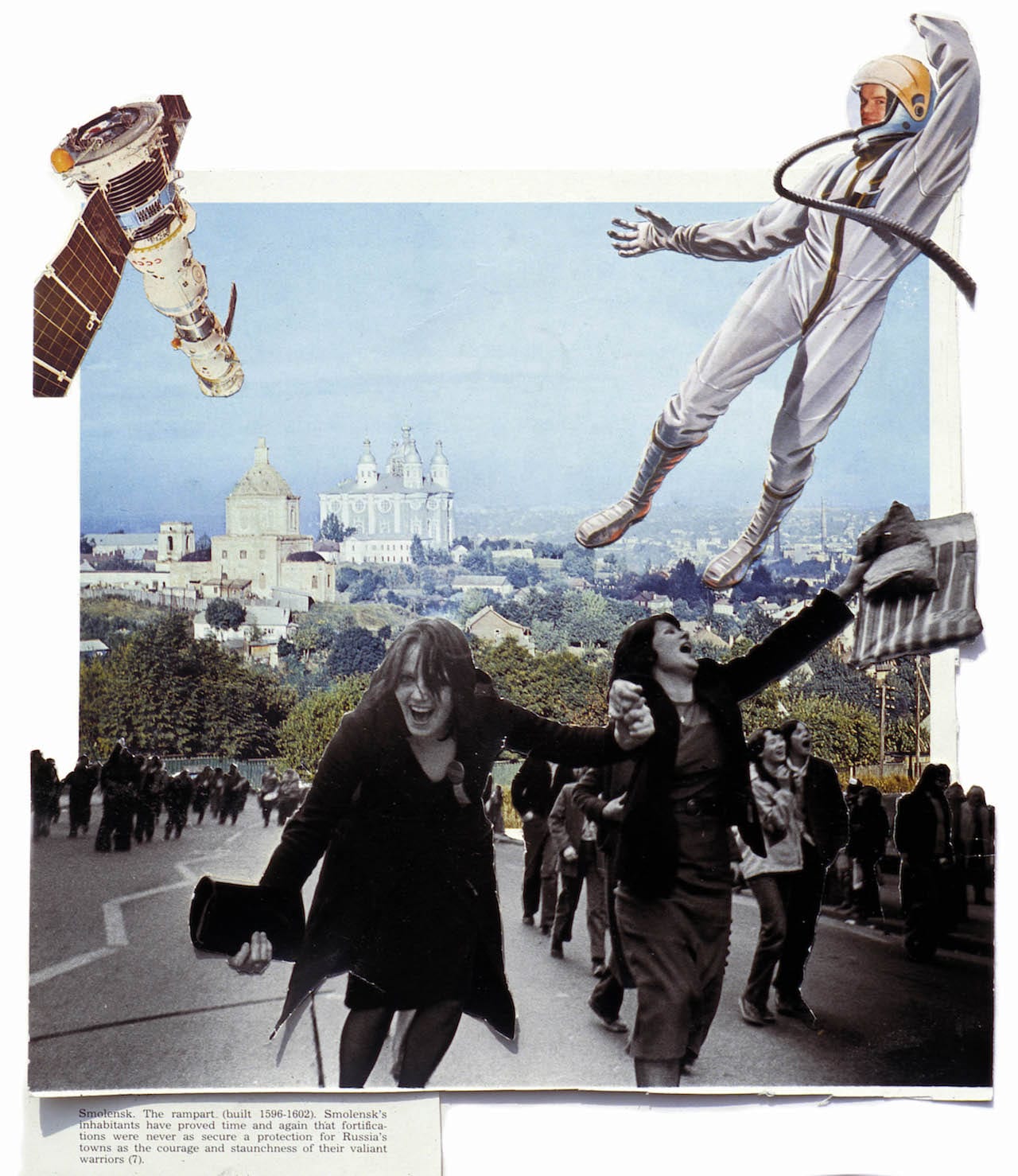

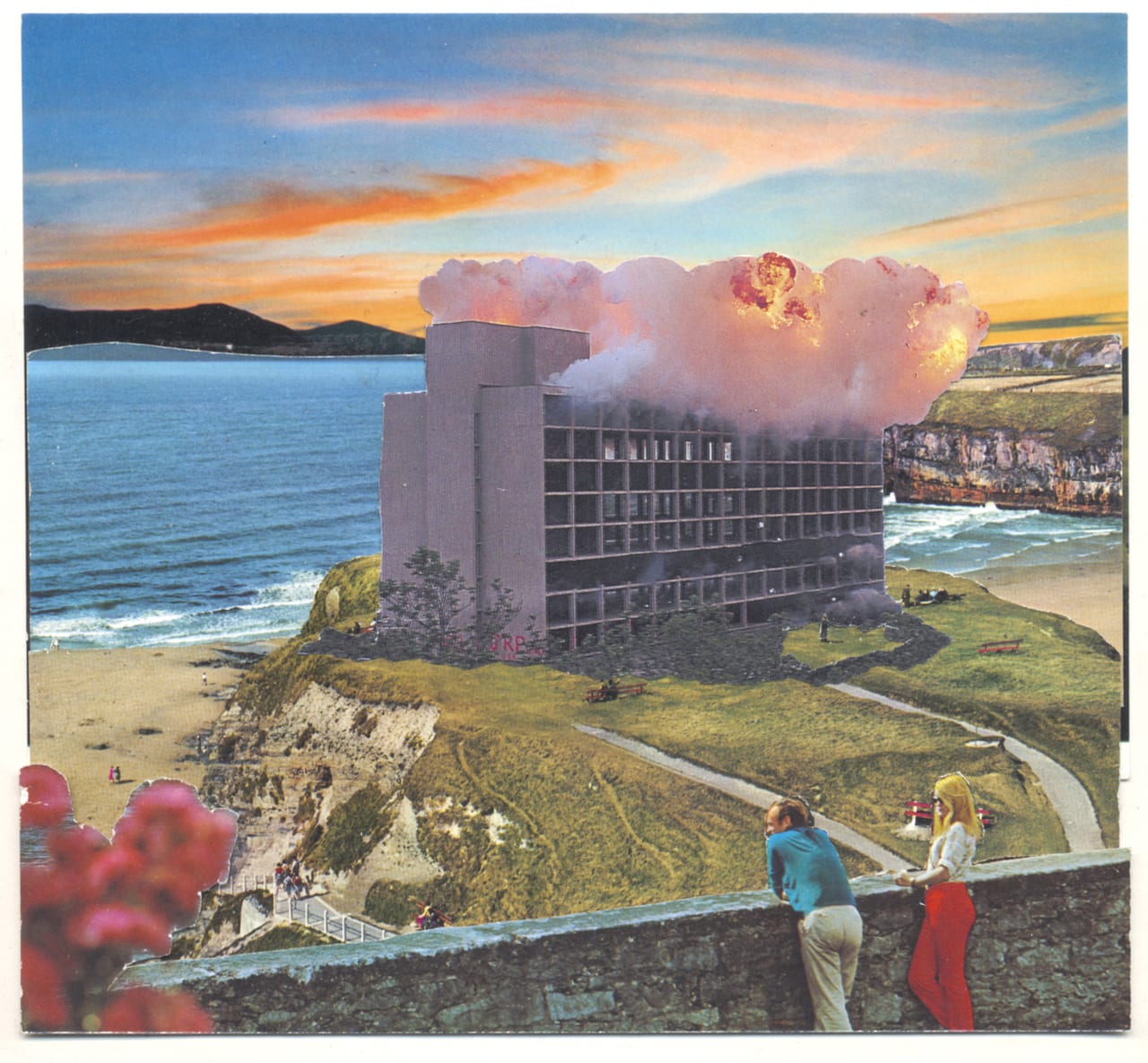

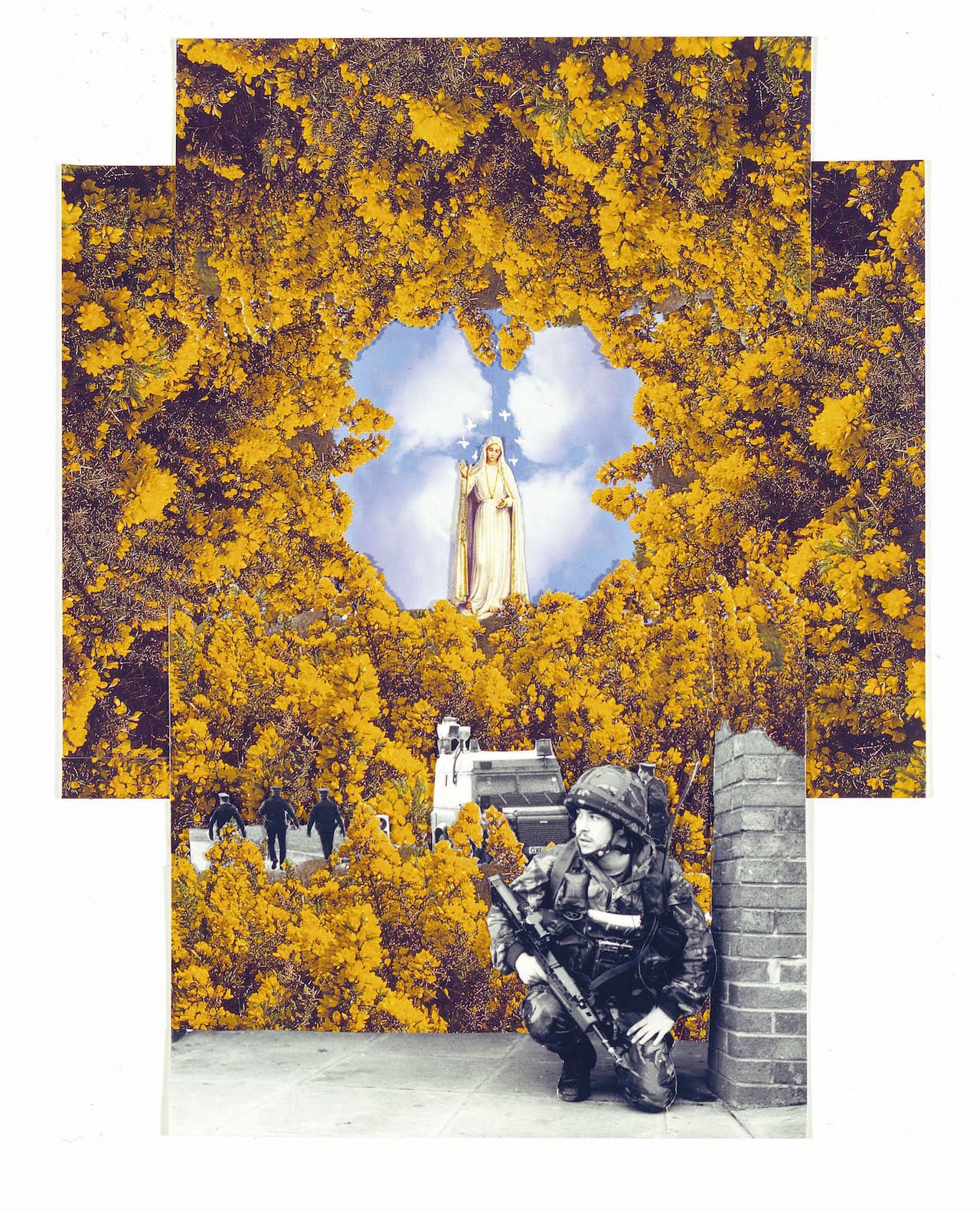

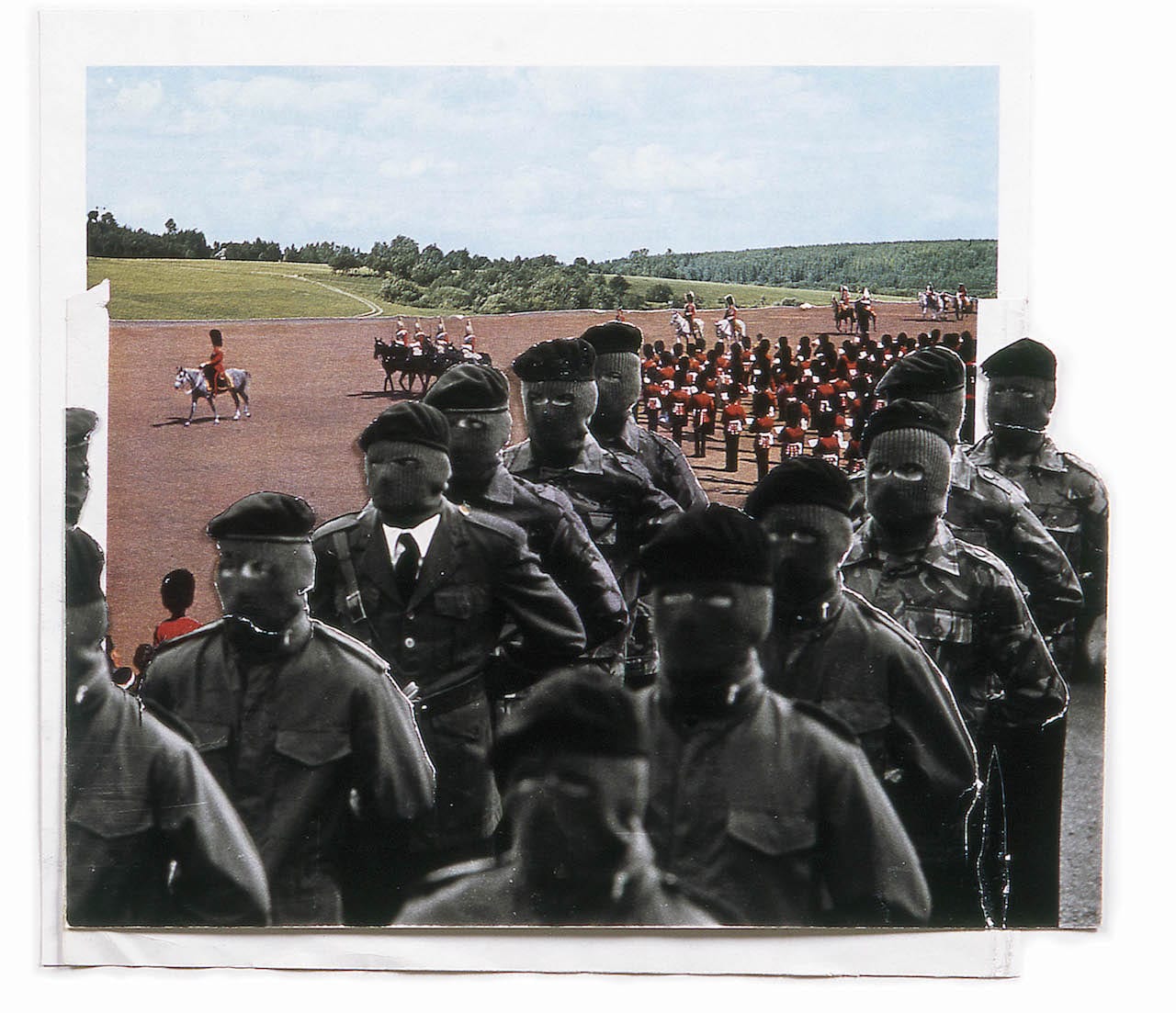

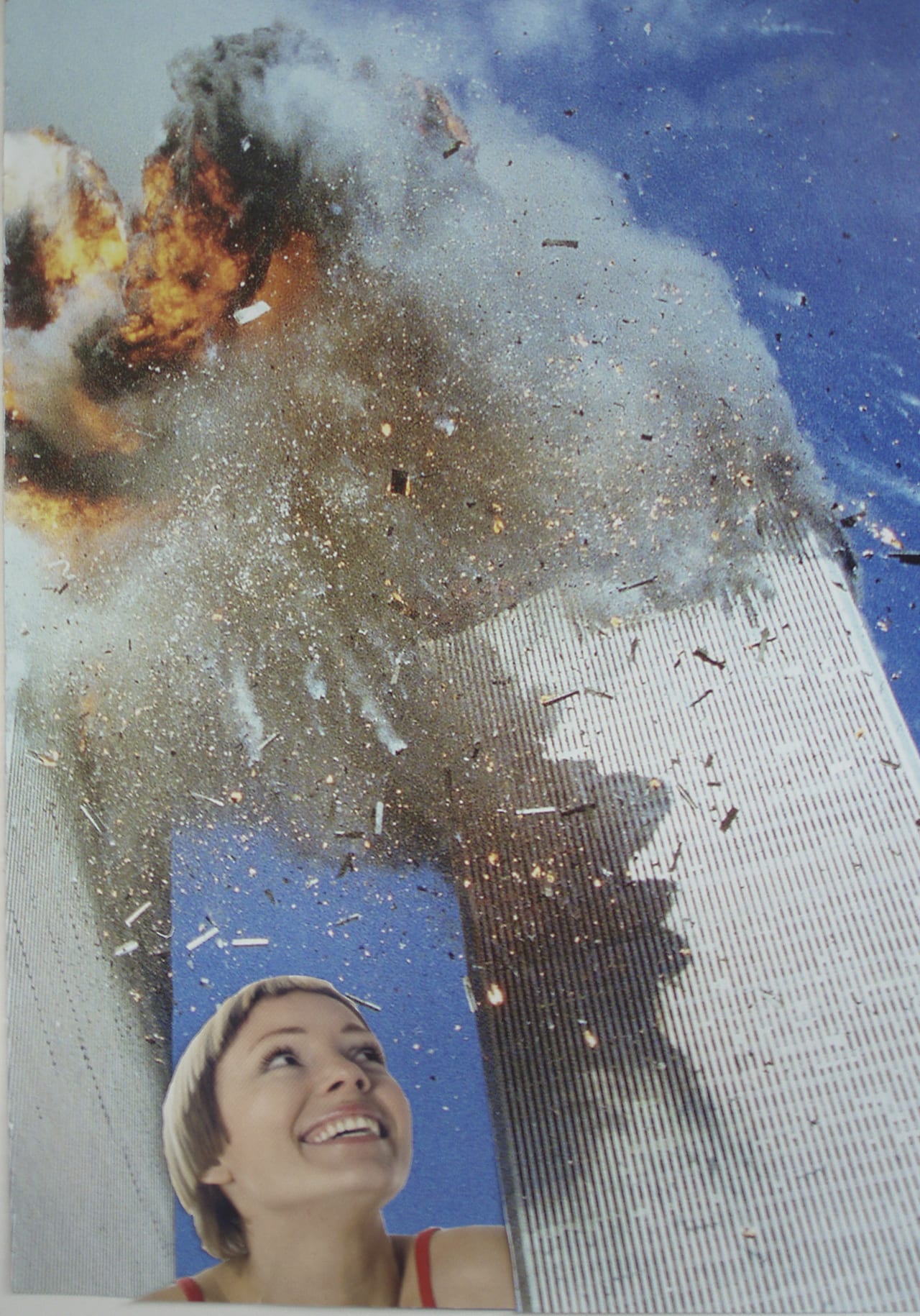

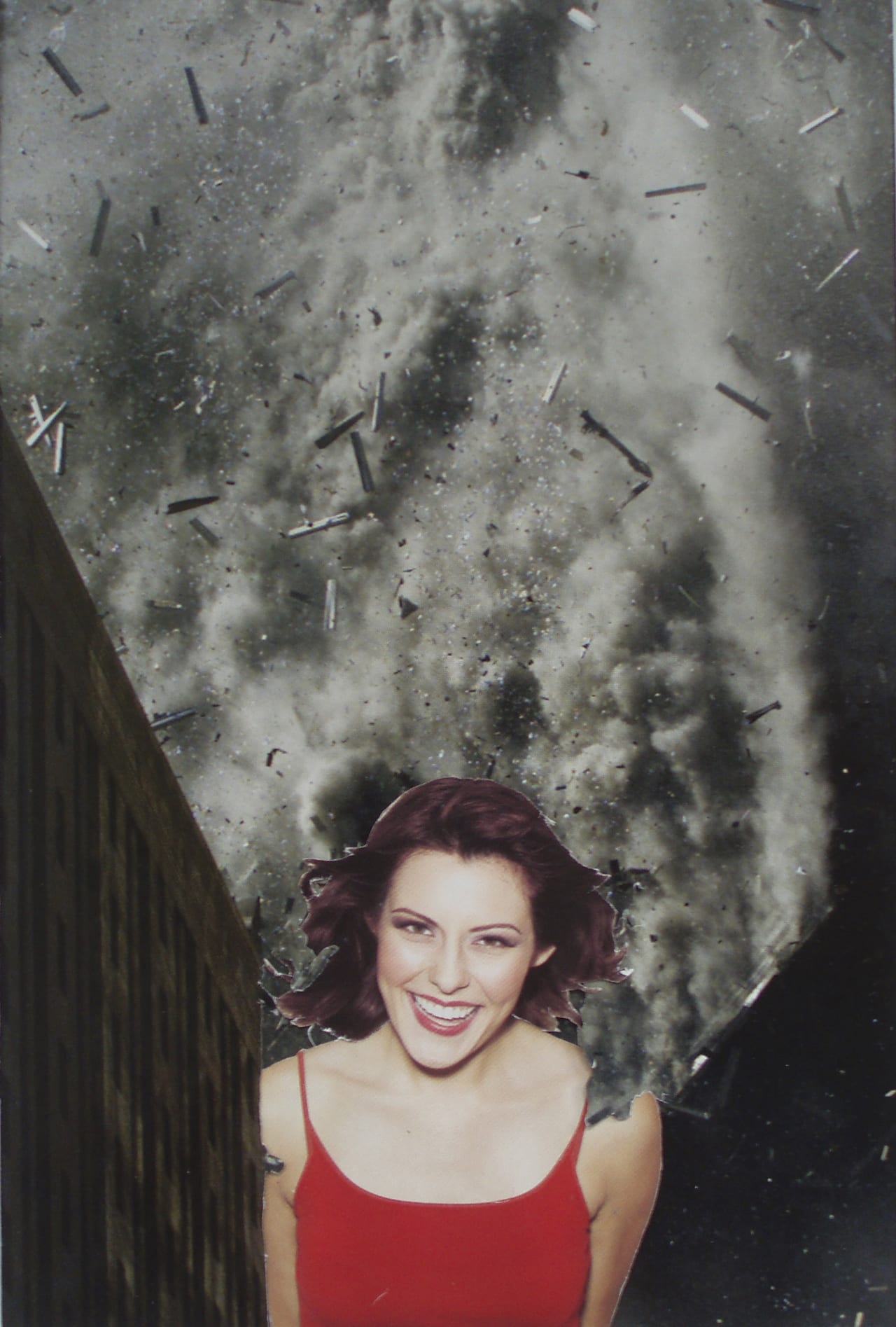

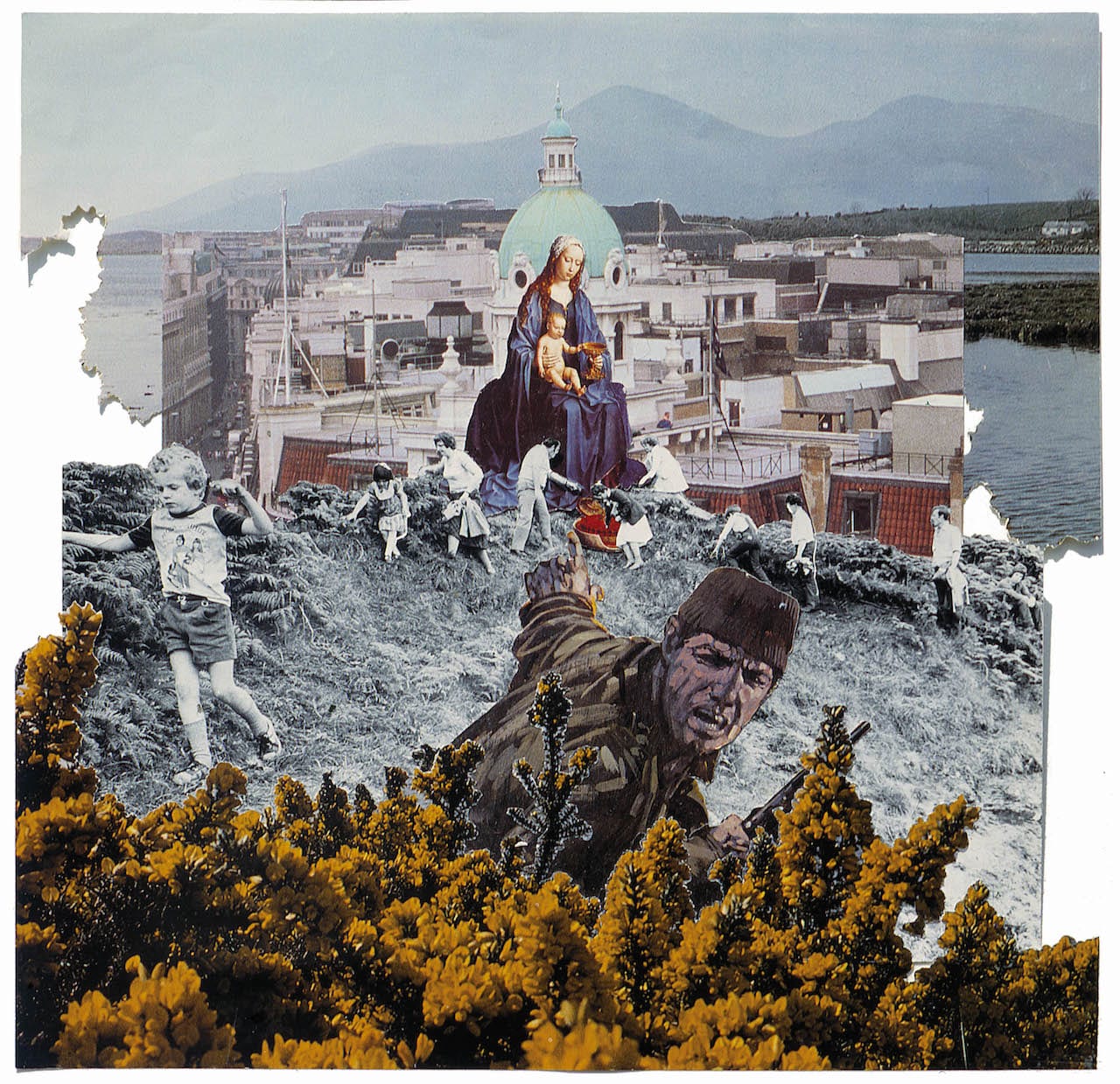

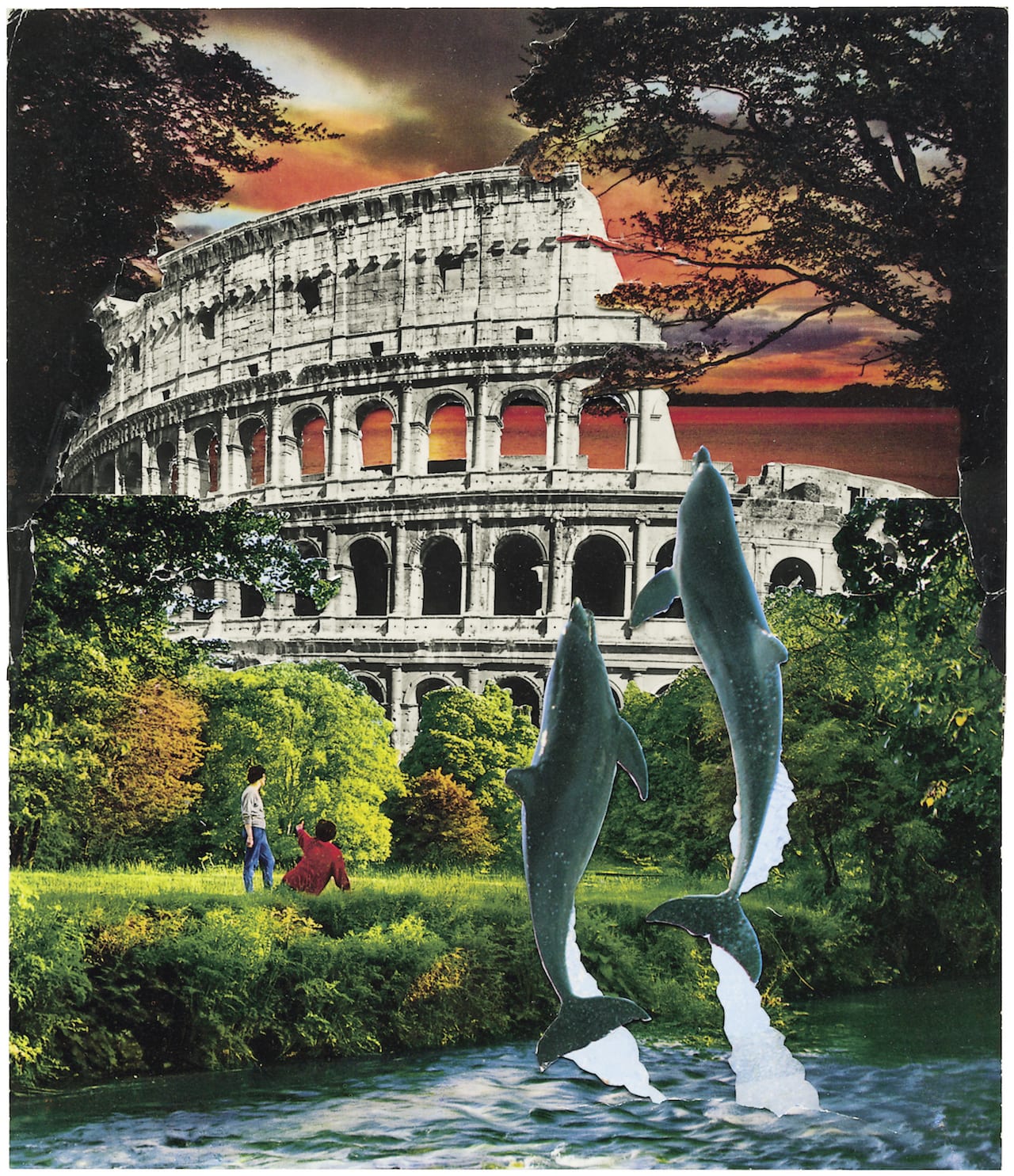

“I realised that I could penetrate the propaganda and the emotional armour that people had to build through the awful, awful conflict. People didn’t want to know about people who blew themselves up in restaurants. I realised that if I could make them laugh, I could get them to think,” Hillen explains. “When you take a photograph, you take a whole world, a cosmos, with you. And then when you collide it with something else you have a whole new level of meaning, entering, penetrating, sliding against one another.”

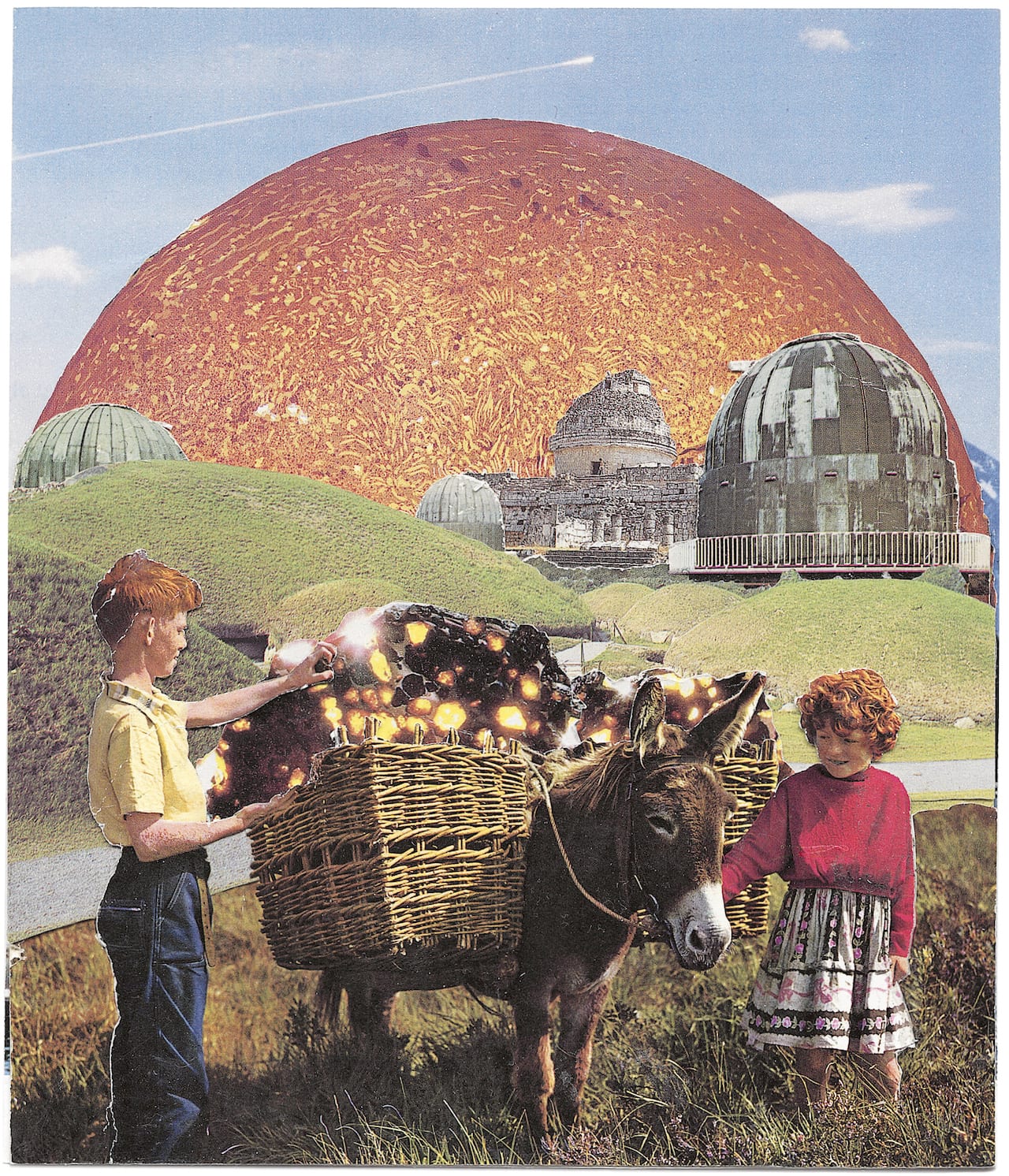

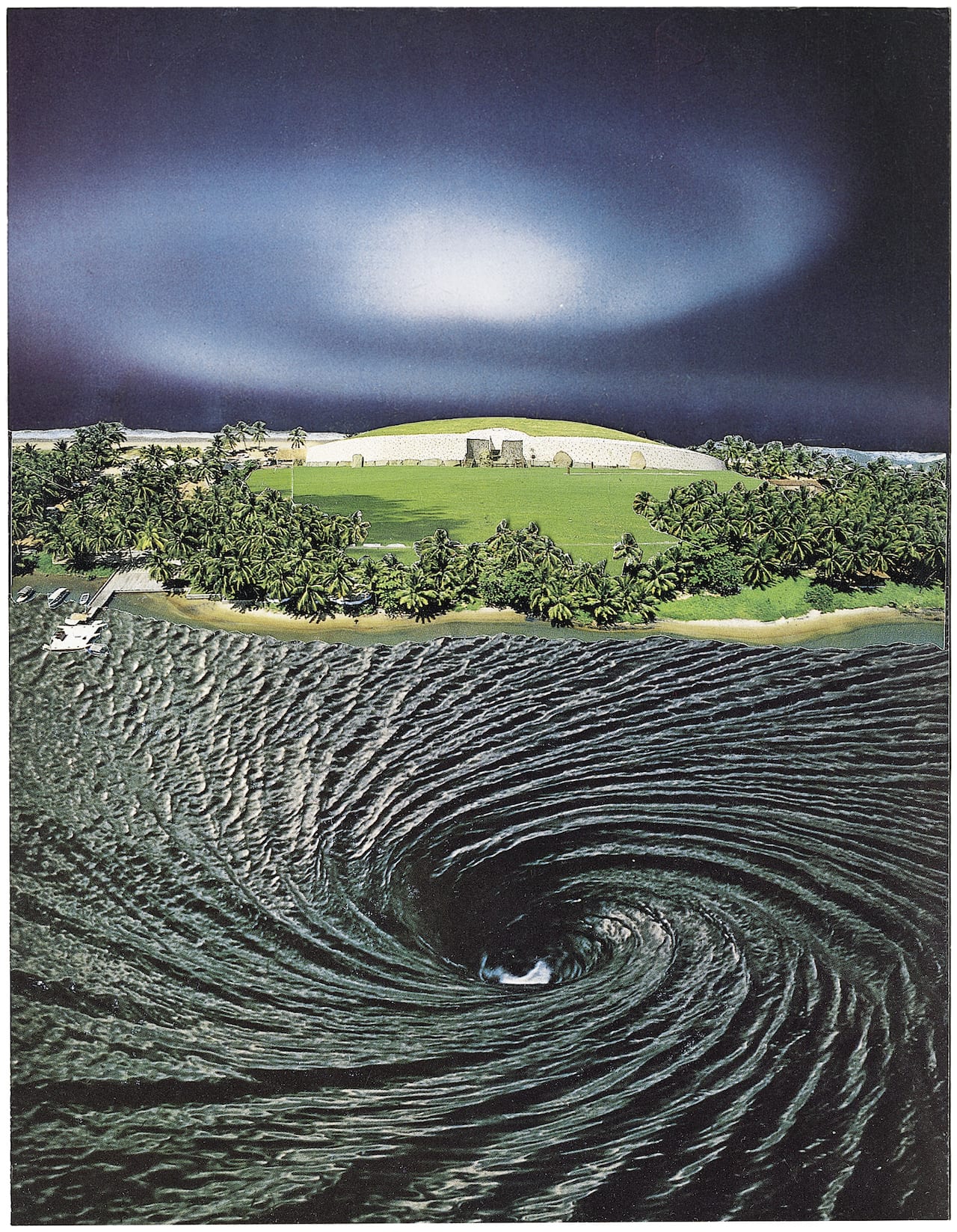

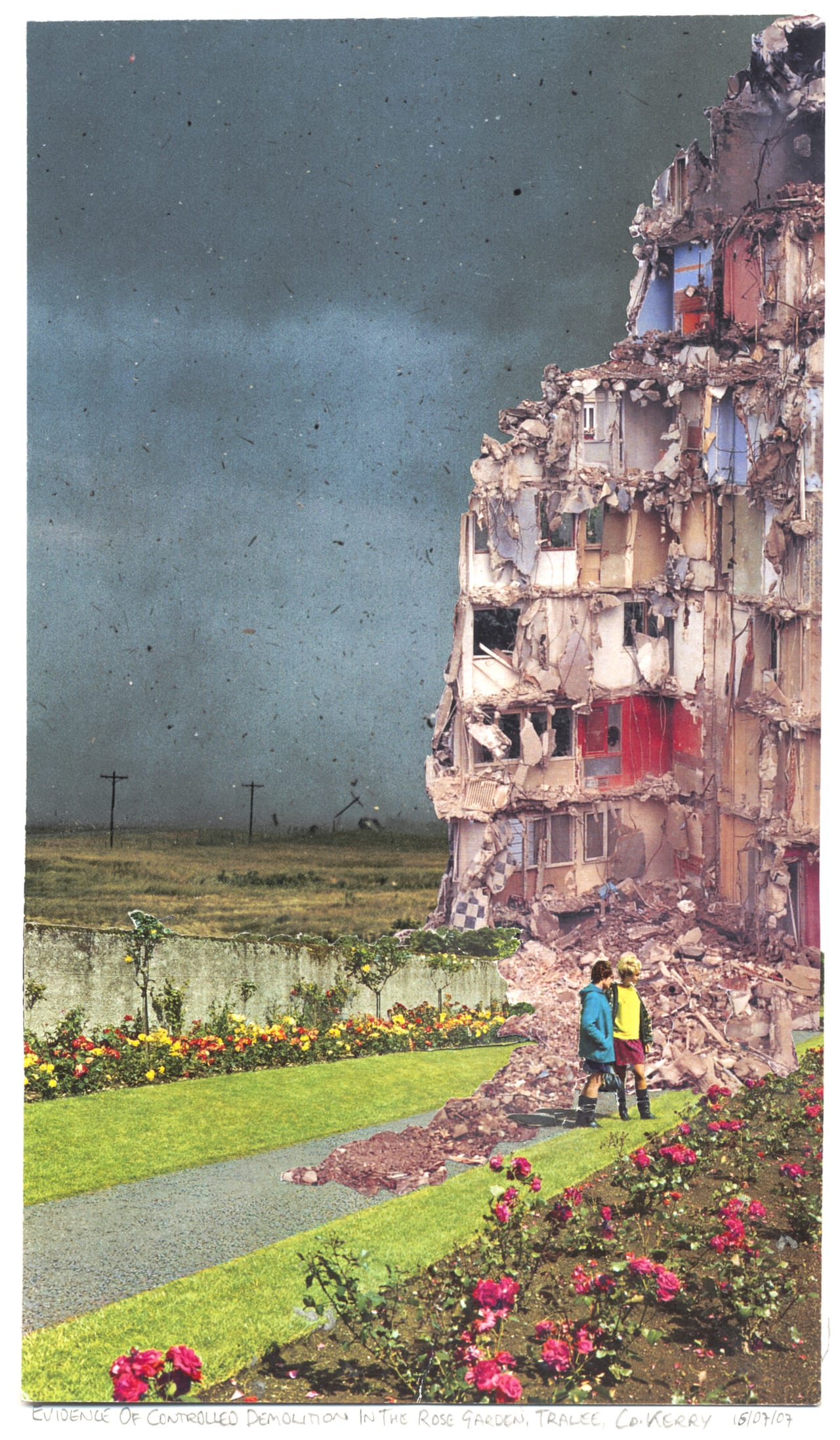

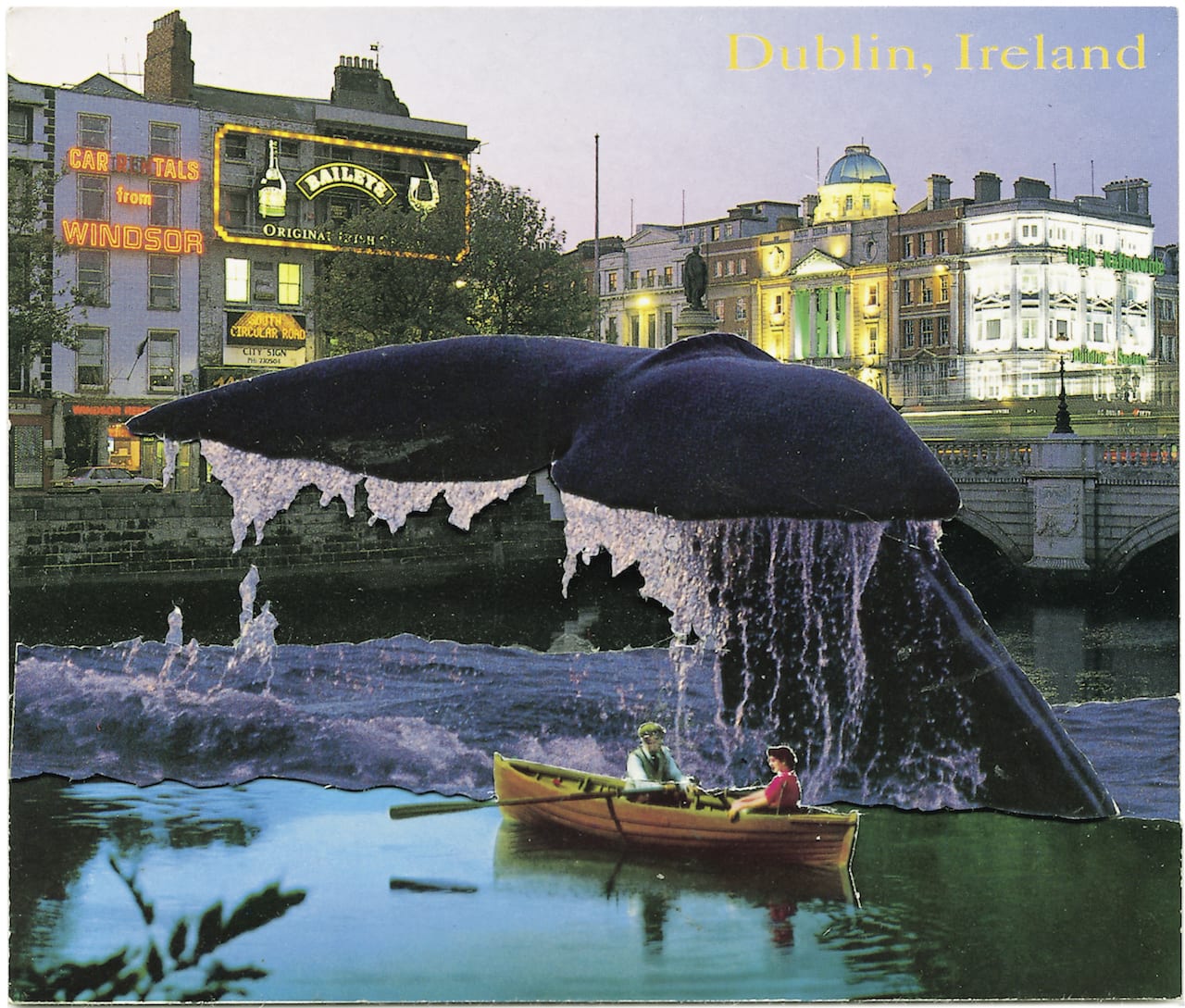

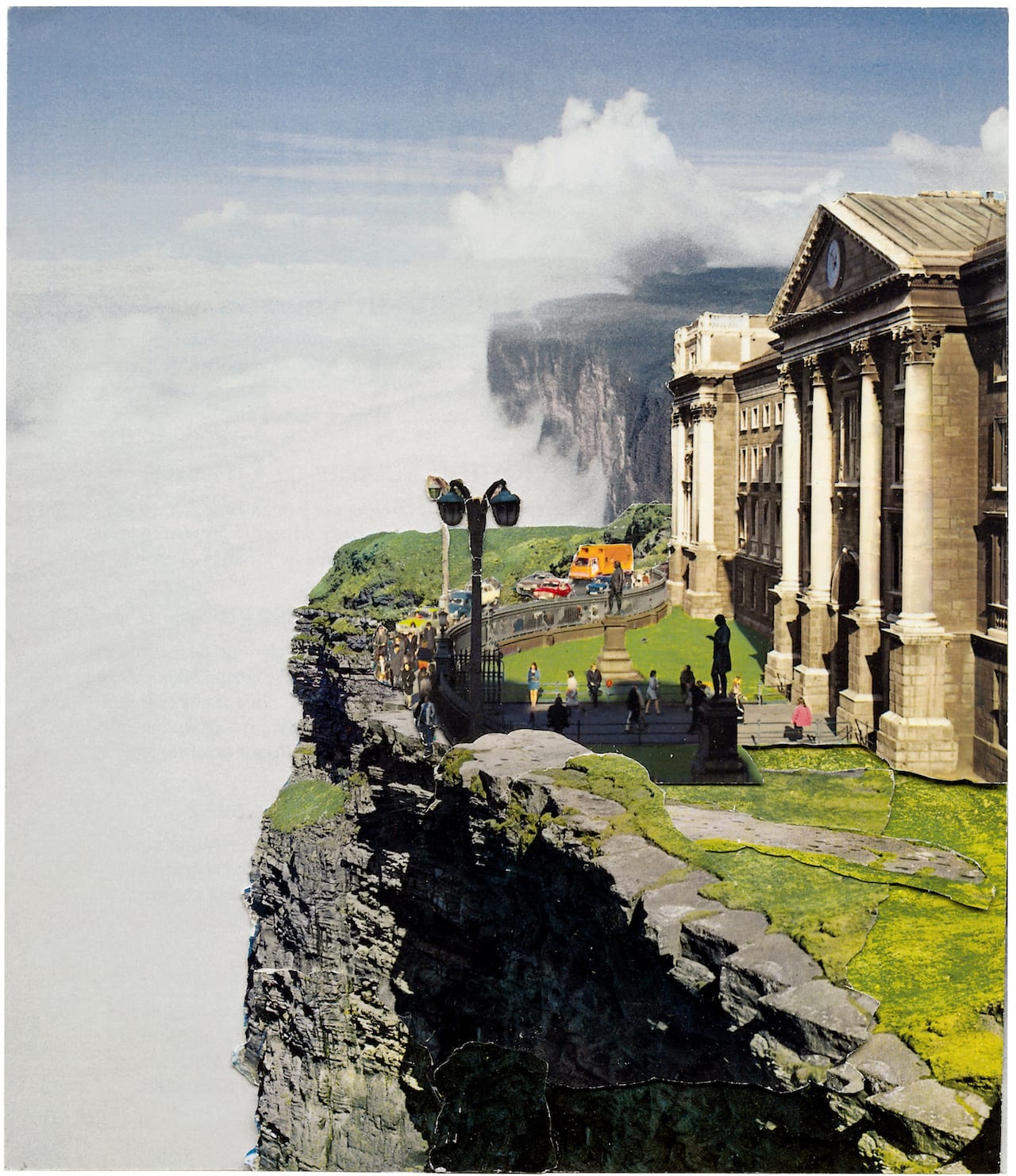

Hillen’s collages are kaleidoscopic, each image carved out intricately and placed with care, layered to give hidden and at-times absurd meanings. “The most important thing about every work is that I want them to be extremely beautiful, and intellectually sound,” he says. His work is reflective of his sweeping interests, which span from photography and art to politics, history, and literature, entering into realms of both fiction and non-fiction; real and imagined. You could examine his work for hours, only to glance back a day or two later and see something completely different, tucked between the alleys of Newry and London, or nestled within the Irish landscape in his series Irelantis.

His work won acclaim and was bought by wealthy art collectors but, throughout the 1990s, Hillen found it increasingly difficult to get his collages into public exhibitions and galleries. “I think it was because the peace deal was coming and people were very anxious about it,” he says, adding that he suspects his work was contentious because it questioned Britain’s involvement in the conflict.

Hillen recalls being cut from what would have been a breakthrough show for him at a major London institution, and receiving a letter from a local library after months of planning, withdrawing the offer to exhibit “due to various pressures”. Losing partners and a lot of money during this period he was very hurt, he says, “it broke my confidence”.

Disillusioned by the London art scene, Hillen moved to Ireland, landing in Dublin in 1993. Between 1994 – 1997 he created his visionary body of work, Irelantis, and in 2007 won the design competition for the Omagh Bomb Memorial in Northern Ireland. But the real turning point in his career – and his life – came just five years ago, at the age of 52, when he was diagnosed with Asperger Syndrome.

“I was stunned – I didn’t even know it existed,” he says, “I knew that I was a weirdo, but I didn’t know why.” After looking into the characteristics of the disorder, Hillen discovered that many of his literary heroes, including James Joyce, W.B. Yeats, and Paddy Kavanagh, were suspected to have had it as well. “We have the Nobel prize winners, and then we have the brilliant failures who drank themselves to death in their 40s. I realised I was in danger of crashing, and I knew which one I wanted to be.”

Two years later in 2015, Hillen entered a series of collages to be exhibited at Format Festival in Derby. A month later he received an email from Erik Kessels, who had seen his work at Format and wanted to enquire about buying it. Hillen explained that most of his work was sold, and ended up telling Kessels his life story. The respected Dutch artist and curator responded by offering to design him a book dummy.

The result, The Wonderful World of Sean Hillen, will be a collection of 100 of Hillen’s best and favourite collages. “Erik designing is a big breakthrough because he has made it so beautiful,” says Hillen, who hopes his work will now be published, seen, and considered, by the art world. “I was very angry and bitter for a long time, but the ground is shifting,” he says. “History has moved on.”

seanhillen.com Sean Hillen is represented in the UK by NickyAkehurst.com, and is currently looking for a publisher to work with on his new book designed by Erik Kessels, The Wonderful World of Sean Hillen.