When the Treaty of Waitangi was signed in 1840, most of the land in New Zealand belonged to the Māori tribes. The treaty prevented the sale of land to anyone other than the Crown, and was intended to protect the indigenous people against other European colonial forces. But within a century, the Crown had either bought, occupied, or outright confiscated huge portions of the country, leaving the Māori with only a few pockets of their sacred land.

The Whanganui river is New Zealand’s third longest river, home to the Whanganui tribes and seen as both their ancestor and source of spiritual sustenance. The land surrounding the river was once one of the most densely populated areas in New Zealand. But with the arrival of colonial settlers, it became a major trading post.

On 15 March 2017, after 140 years of negotiation – New Zealand’s longest-running litigation – the Whanganui river was granted the same legal status as a human being, meaning it would be treated and protected as an indivisible whole. Hundreds of members of Māori wept with joy as the lifeblood of their tribe, from which they take their name, spirit and strength, was given recognition as one of their ancestors.

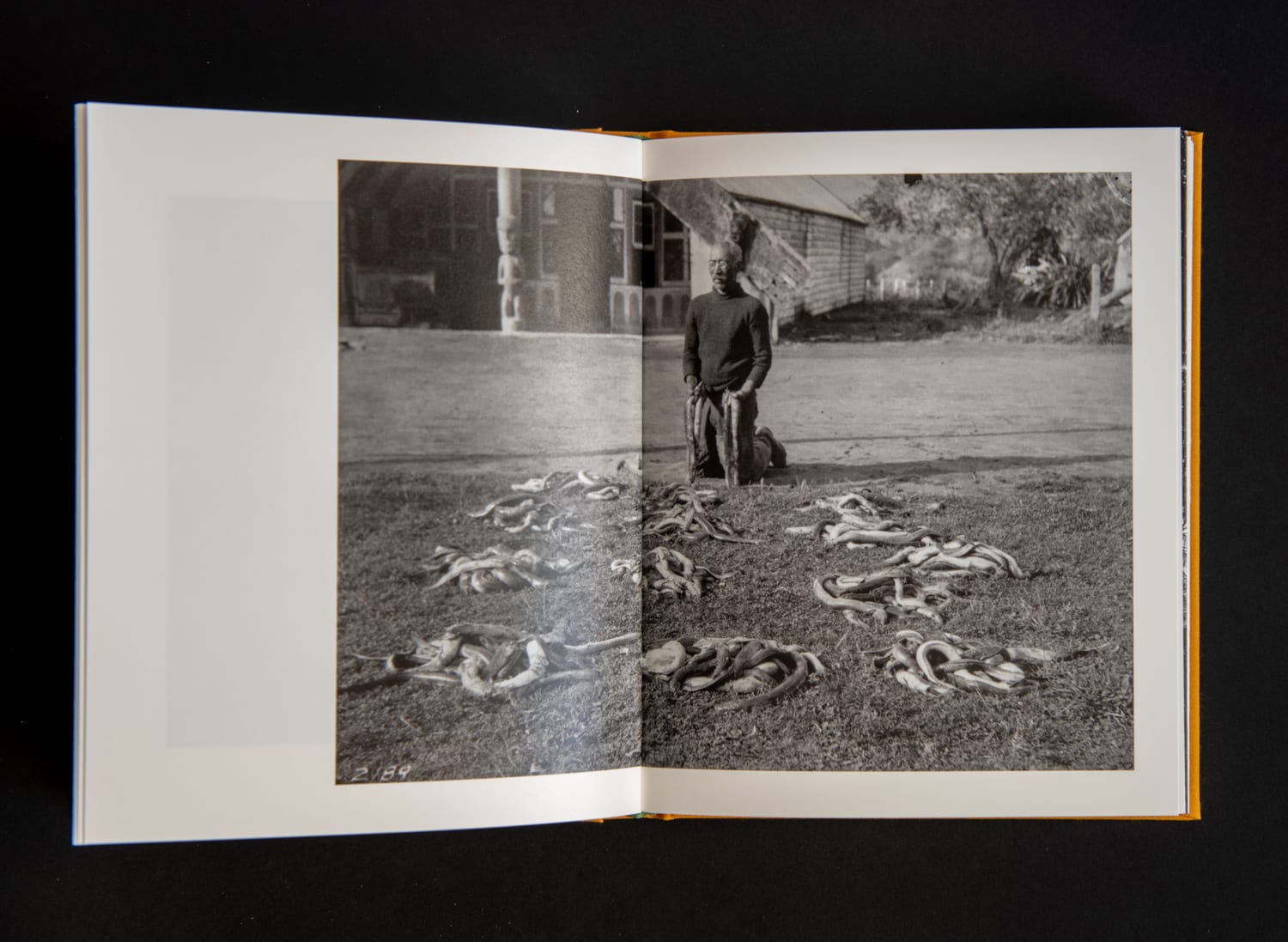

In his new book, Te ahi kā, Martin Toft explores this physical and metaphysical relationship between the river and the Whanganui tribe, and his own spiritual connection he had when visiting them between 1996 and 2016. An amateur photographer at the time, Toft decided to do his first serious photography project on the indigenous people in New Zealand after spending a year living there in 1995. Travelling down the Whanganui river, he met a tribe who wanted to claim back their spiritual home, Mangapapapa, on the steep river banks in Whanganui National Park.

Though his presence was met with scepticism at first, Toft was eager to be accepted by the tribe and to join them in re-occupying their land, so he spent two months learning their language and eventually gave a ceremonial speech in front of the whole community. Since he had a camera, Toft was put in charge of documenting the journey, and was blessed with a Māori name, Pouma Pokai-Whenua. ‘Pou ma’ means “white post”, a reference to his skin colour and the post of the sleeping tent he put up when they first made camp, and ‘Pokai-Whenua’ is adopted from the name of a celebrated 14th century explorer who travelled from village to village making peace.

But though Toft had been accepted as one of the tribesmen, in 1996 his visa ran out. His Māori family wanted to challenge the immigration authorities, but eventually he left to live in London. 20 years later, when he heard about the Whanganui River Deed Settlement, Toft returned. He collected more photographs and gained permission from the tribe to use them in his book, Te ahi kā, which is made up of images from his two trips, 19th century archives, and Māori family albums.

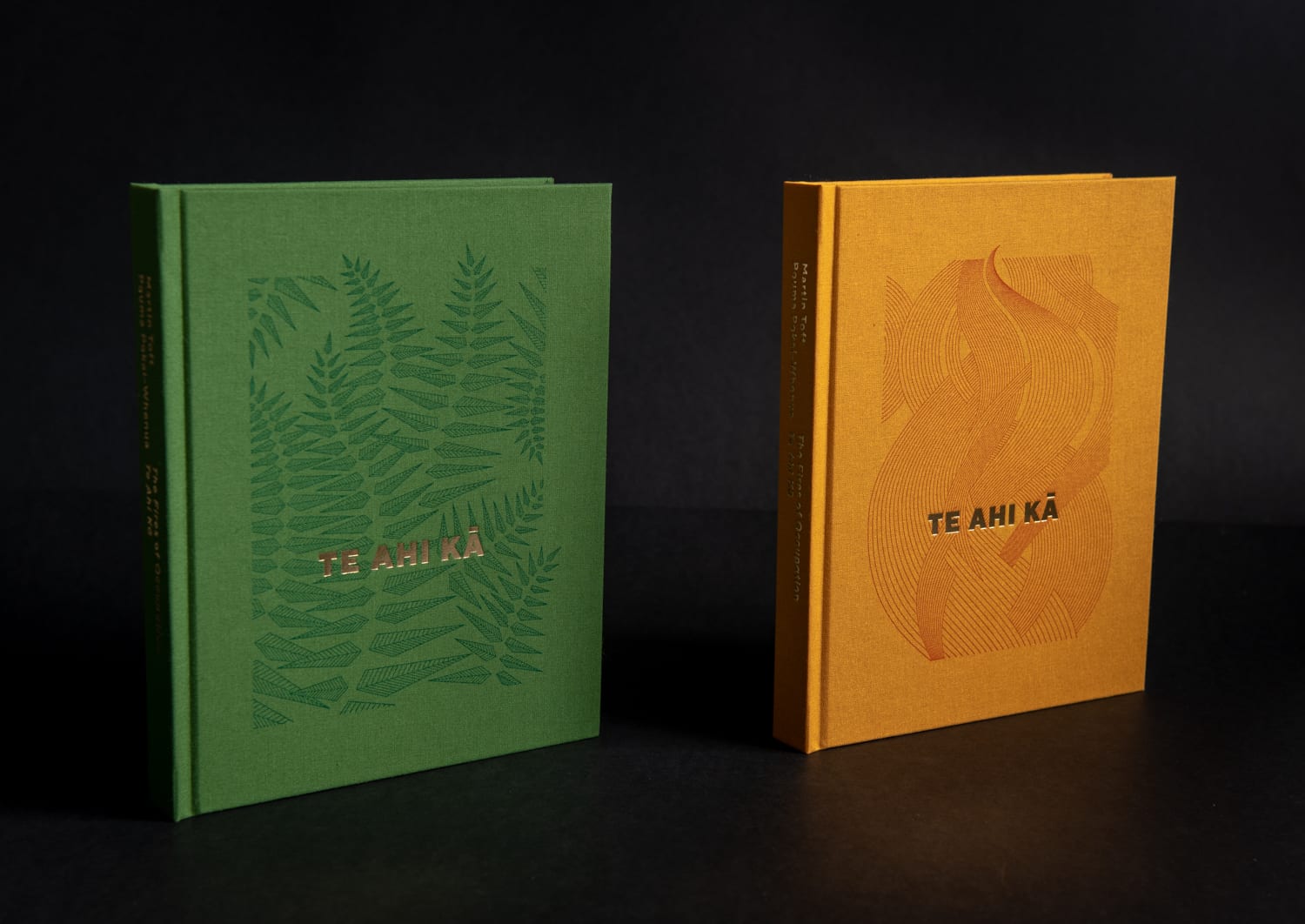

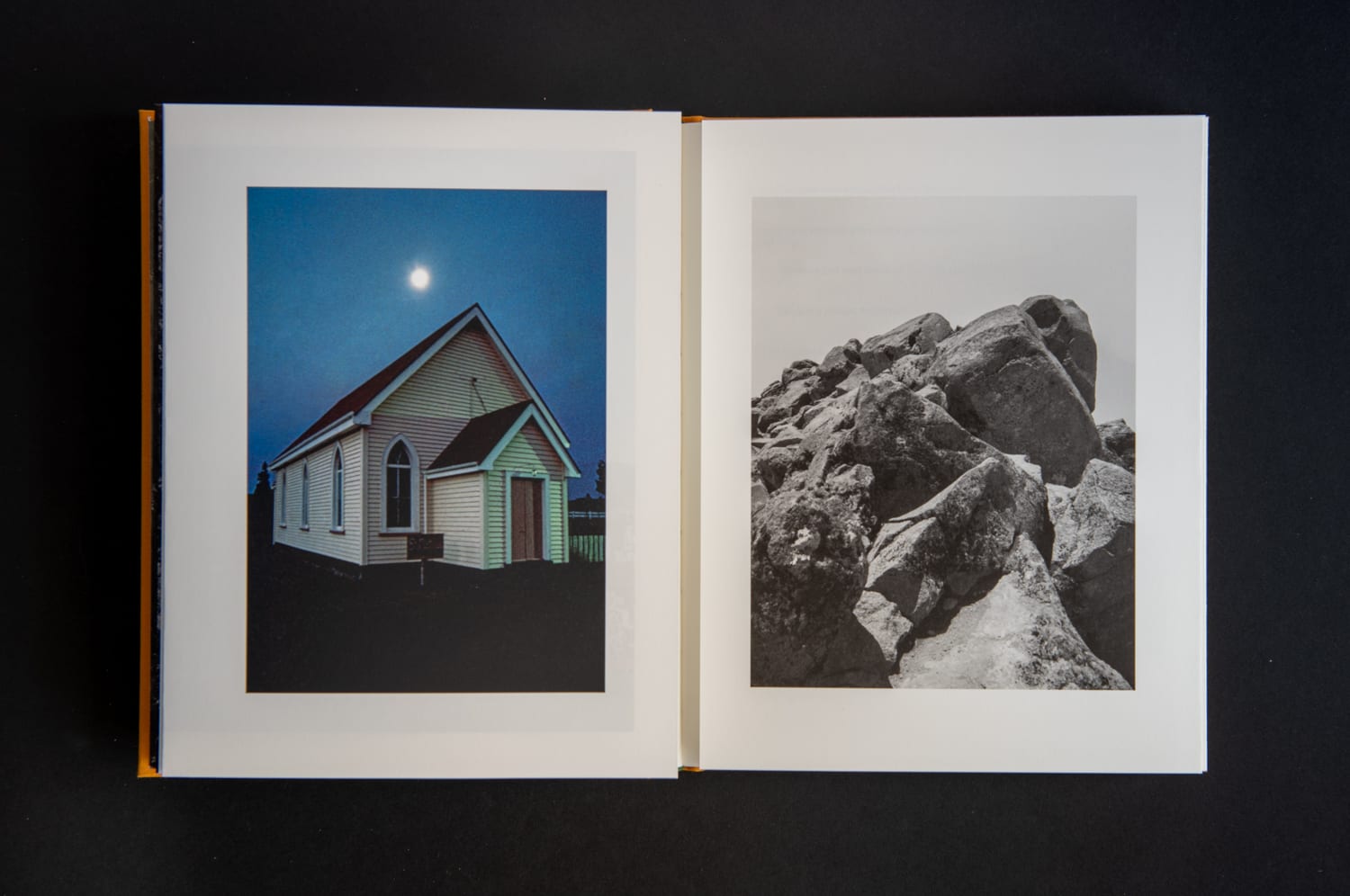

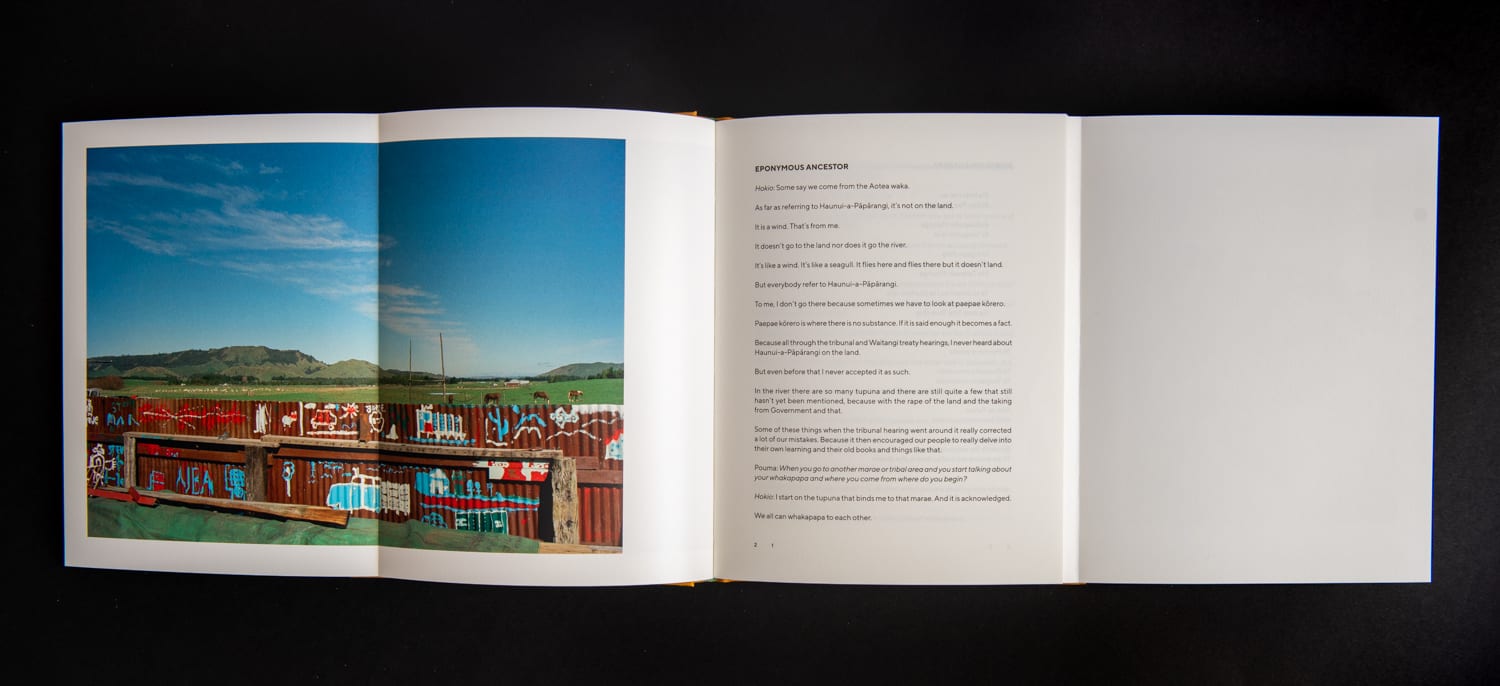

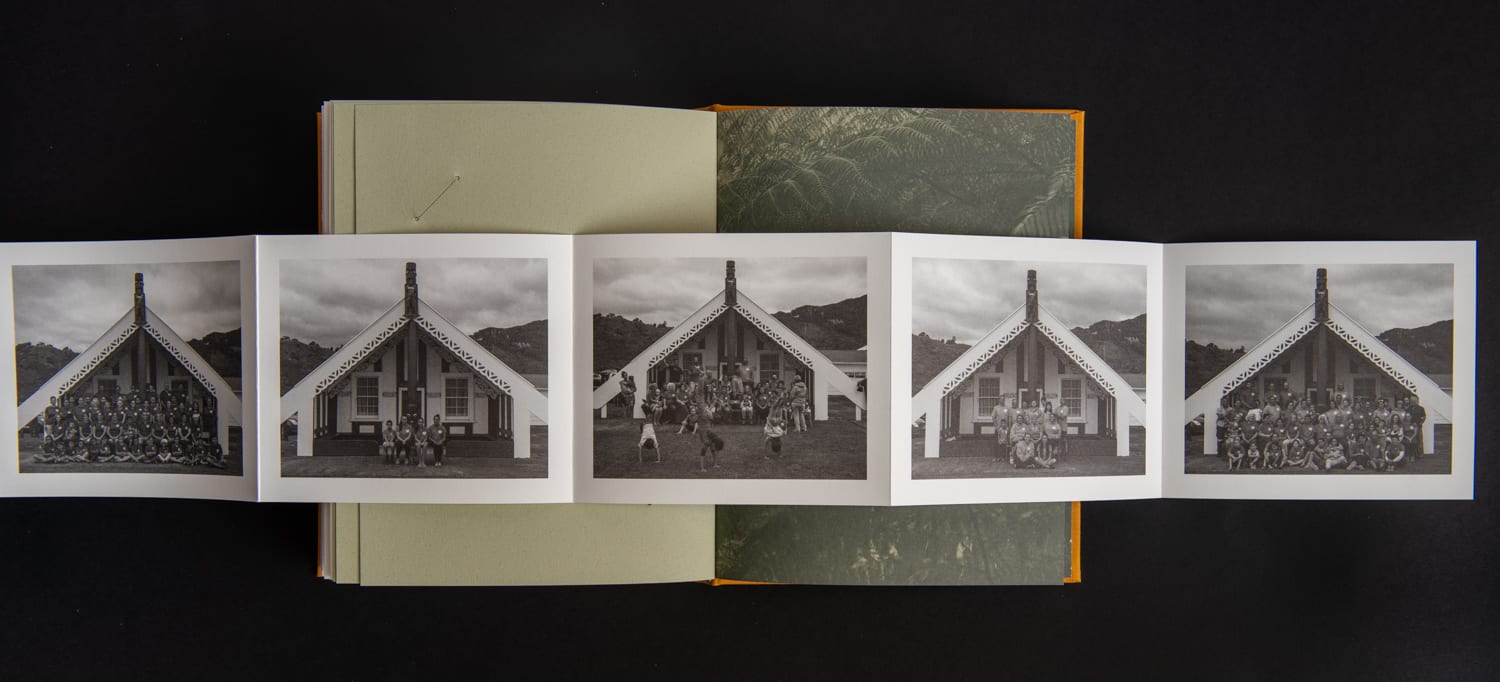

The two cover variations are a tribute to Māori traditions. One is designed to represent a fern leaf, which Māori women use for purification, protection and prayer, and the other with flames, which the men use to transport fire through the villages – a symbol of occupation. The book is designed to flow like a canoe trip down the Whanganui river. When travelling with the Māori, they will stop the canoe to tell stories about the land and their ancestors, which is reflected in the seven hidden chapters of text that fold out of double page spreads. They include important conversations from Toft’s trips as well as the Crown’s official apology and acknowledgement for breaching the terms of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840.

For the Māori, the trees, the rocks and the water are all seen as treasures. “We, in the western, developed, industrial world, have lost sense of our connection to the land,” says Toft, “We can learn a lot from how they respect and preserve nature to sustain life. We are waking up now, we’re realising that we need to protect the environment that we live in.”

www.martintoft.com Te ahi kā is published by Dewi Lewis, available to purchase for £35 www.dewilewis.com