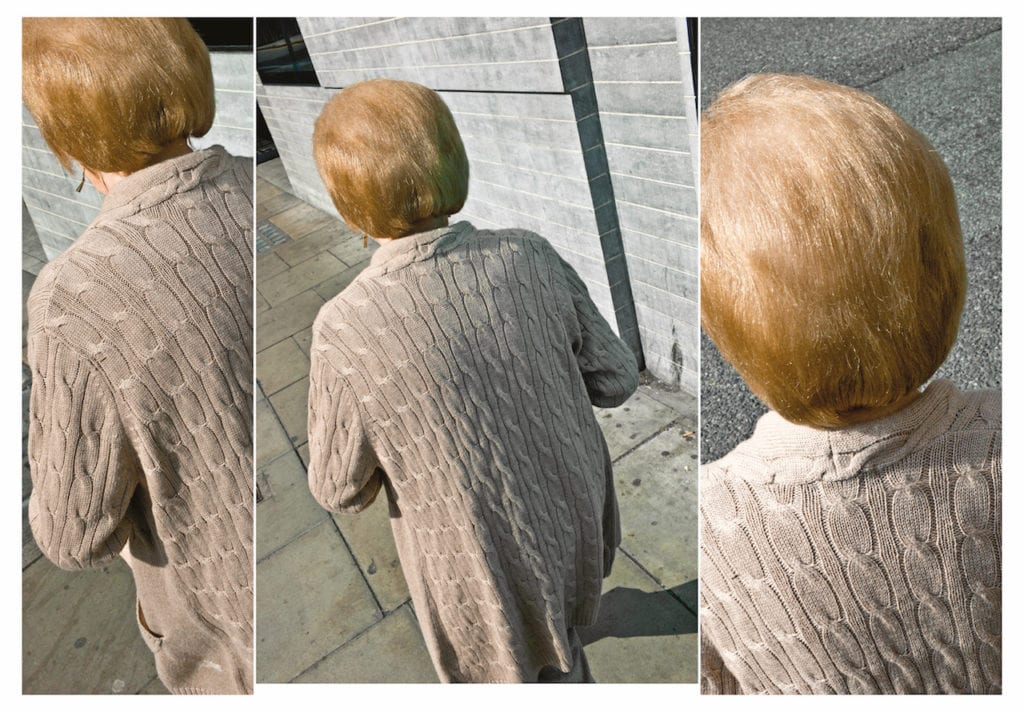

It’s five years since Eamonn Doyle first showed his acutely angled photographs of elderly Dubliners set against the grey-slabbed terra firma of the city’s streets. Soon after, Martin Parr picked up the scent, and word quickly spread.

His book, i, sold out, and Doyle was taken on by Michael Hoppen Gallery in London, who exhibited his work at Paris Photo later that year. There followed two further sell-out books in his Dublin trilogy, On and End; a critically acclaimed show at Rencontres d’Arles; and a group exhibition at Pier 24 in San Francisco, where his work was shown together with Diane Arbus and Lee Friedlander, alongside contemporaries such as Alec Soth and Vanessa Winship.

Doyle’s rise to cultish devotion is nothing new. He studied photography at Dún Laoghaire College of Art & Design, graduating in the early 1990s before taking off to travel around Central and South America. He returned to Dublin fully intending on a career in photography, but instead went on a massive side swerve for the next two decades, immersing himself in techno music, first as a DJ and then moving into production, setting up D1 Recordings in 1994.

Named after the north-of-city-centre postcode in which he lived and based his operations, the record label went on to become something of a Dublin institution. He opened a record store and a music distribution company, then set up and ran the Dublin Electronic Arts Festival (DEAF) for a decade up until 2009, around which time he grabbed his Leica again and started taking photography seriously once more.

Not wanting to pick up where he left off, he challenged himself to photograph in colour, and avoided shooting in landscape, working around the D1 neighbourhood. The results, curiously simple yet effective, became i, the publication that Parr would describe as “the best street photobook in a decade”. His success, then, has been both stratospheric and long in the making. But considering what’s in the works, 2019 is the year that everybody is going to know his name.

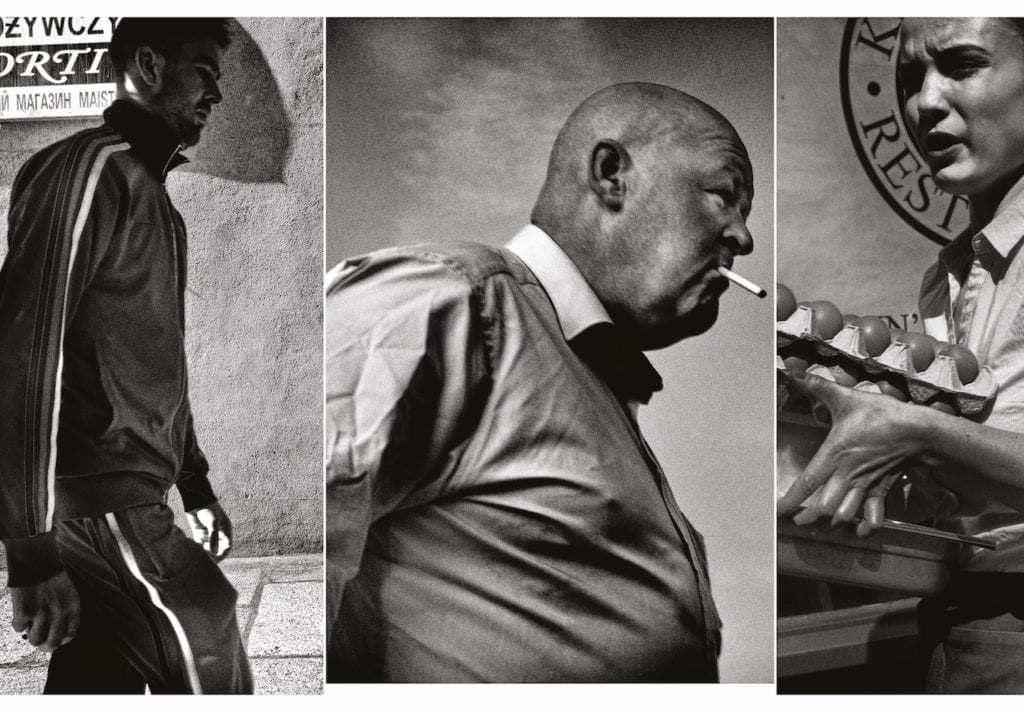

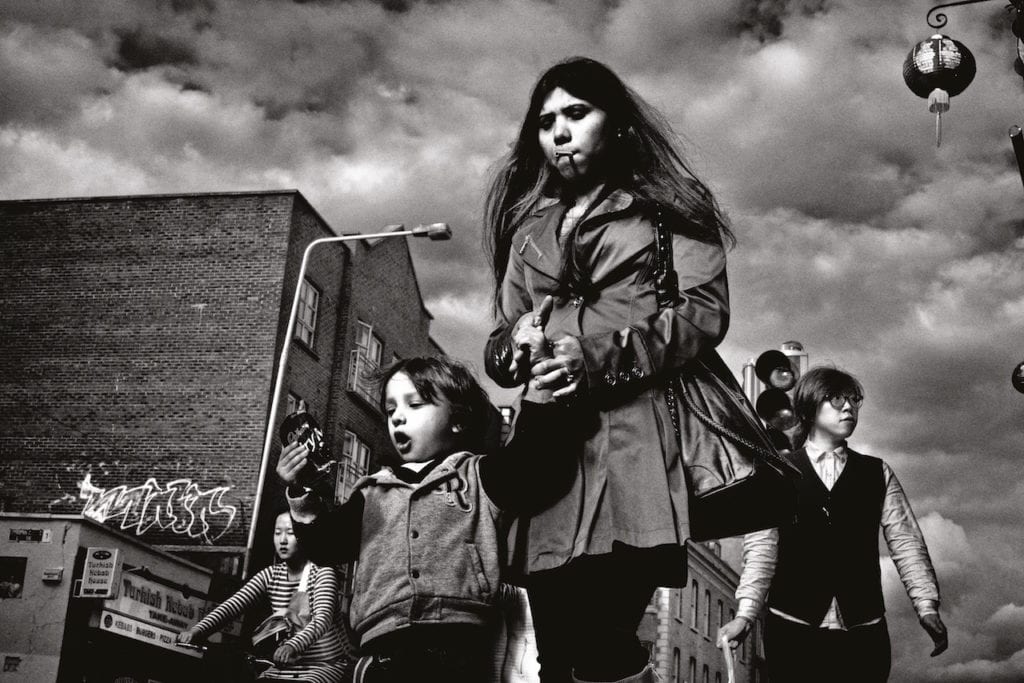

This spring, Thames & Hudson releases Made In Dublin, an anthology of his work to date from his home city, gathering previously unpublished photographs alongside text by award-winning Irish author Kevin Barry, and an introduction by Irish critic Sean O’Hagan. This “exhilarating surround-sound, cinematic experience in book form” is designed by his long-time collaborator Niall Sweeney, presenting 370 images and illustrations across 272 pages, encompassing full-width bleeds, sequences, tints and graphic elements to dazzling effect.

Sweeney’s copious portfolio under the moniker Pony Ltd (cofounded with Nigel Truswell) deserves separate scrutiny. The text mentions how the book restages “the intertwined looping dramas of the physical city, its light and texture, its psyche, and the movements of its people, as they unfold and pass through”, and his fearless use of images as graphic elements makes the work feel new, even for those who know the original works.

Doyle says that Barry’s “visceral words now feel embedded in the Dublin trilogy”, and here he contributes to the narrative with suggestive notes from a Dubliner’s daily life, its sensorial experience of the everyday. Barry’s affecting words introduced in this context are a welcome counterpoint to the visual storytelling. No doubt Doyle and Barry set here the beginning of a collaboration which will bear more fruits in the future.

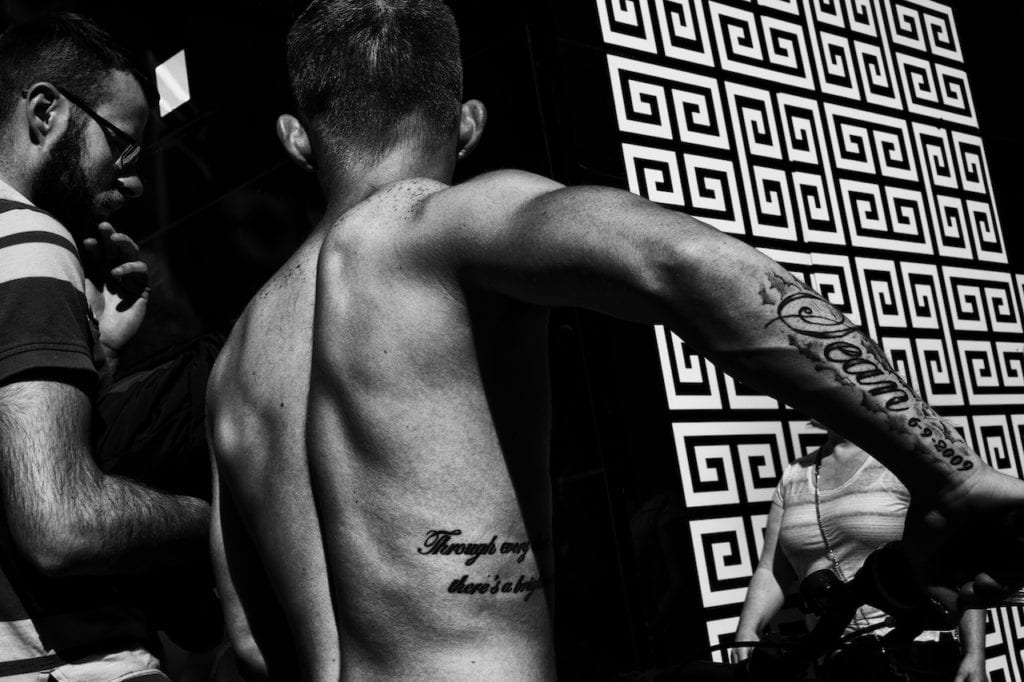

The book launches in Dublin as part of the St Patrick’s Festival programme, coinciding with Doyle’s exhibition at the Royal Hibernian Academy. It is presented in association with the Fundación Mapfre in Madrid, which is staging a large-scale show of his work from September through to next January. Visitors can expect to see the signature grid-style installations that so impressed in Arles, along with larger-than-life prints from his latest series, K – shot in the west of Ireland – a lament to grief, hung in walnut frames to create what he lightheartedly defines as “a wall of ink and wood”.

Alongside K, nine screens – more than 6m in length – will complete an immersive video installation of End (with an audio track that includes Barry’s voice and texts, and new music by David Donohoe), while the gallery walls will be devoted to work from both i and On. Surprisingly, this will be his first solo show in Ireland, in his home city, and only the second of his career after that pioneering exhibition in the south of France. And if that wasn’t enough, the St Patrick’s Festival will also celebrate the 25th anniversary of D1, with a new record release and a retrospective exhibition with all the materials produced throughout its history.

Adding to the demands of preparing such a complex exhibition at the RHA, Doyle plans to release a six-piece vinyl album set featuring 55 new tracks from 45 Irish and international artists that contributed to the record label’s success. D1×25 will be launched and celebrated over the weekend, culminating with a gig gathering D1 artists together.

Doyle’s creative relationship with Sweeney goes back to the early days of D1, and later they started making publications together for DEAF. Seeing some of the printed programmes they created, you appreciate the genesis of the graphic vocabulary that would later populate Doyle’s books. His other long-time collaborator, David Donohoe, who composed the sound work for End – “tracing a coiled beat around the city”– and the reworked grieving lament in K, was also involved in D1 as a recording artist, and made further incursions in experimental music with Doyle on a project called String Machine.

It is interesting to hear an anecdote by Doyle from Arles regarding these long-term collaborations, and their manifestations in the photobooks. At the end of a talk about their practice, where Doyle, Sweeney and Donohoe spoke, someone raised an objection during the Q&A: “This is all rubbish! I think you are just three friends doing work together”. Doyle responded with a chuckle: “That is exactly what we are; that is what we have just been telling you.”

The idea is simple: to fix in time the individual creative processes, to rub these personalities against each other, just as it happens in those streets every day. And if one factor could explain Doyle’s recent success with his photobooks – or, even, his wider creative oeuvre – it is not just an evident aspiration to overachieve, to deliver beyond what is expected, but the fact that he truly understands the power of collaboration in creative processes.

Here, the key element is labour, his honest and humble approach, coupled with a relentless entrepreneurial mindset, and identifying the right people to collaborate with which really define his creativity. Indeed, when his nine-screen installation goes on show at The River Rooms in Somerset House as the centrepiece of the public programme of this year’s Photo London (16 to 19 May), it will be billed as co-authored by Doyle, Sweeney, Donohoe and Barry. And when attention turns to the Fundación Mapfre show in Madrid four months later, Sweeney will step forward as the curator of an ambitious exhibition that will be presented as an overview of his practice, containing material from as early as his college years, and including his photographic work for D1 and DEAF, all the way through to his series, K, and newly commissioned work produced in Spain.

The accompanying publication, contextualised with essays by key figures, will divert from Mapfre’s well-known template, thanks again to Sweeney’s touch. In this way, Doyle’s name will join a glorious list of artists in the book series, from Paul Strand and Brassaï to Peter Hujar and Hiroshi Sugimoto. With regards to what else we can expect in the coming years, though Doyle considers possible collaborations in time-based media, he loves making photobooks. For him, these are the crux of his works, while gallery prints “are quotes from the book”. In this new-found cottage industry, he has encountered a parallel with his heyday running a record label: the limited editions, the collectors, the preciousness of the physical artefact, the same layers, and often created with the same set of people.

Eamonn Doyle’s immersive nine-screen installation – shown in Dublin in March 2019 as part of the St Patrick’s Festival programme – is currently being exhibited at The River Rooms in Somerset House as the centrepiece of Photo London’s public programme (16 – 19 May). A major exhibition of his work is currently on show at Michael Hoppen Gallery in London, until 15 June 2019

eamonndoyle.com

photolondon.org

This article was originally published in issue #7882 of British Journal of Photography magazine. Visit the BJP Shop to purchase the magazine here.