This article was originally published in issue #7894 of British Journal of Photography. Visit the BJP Shop to purchase the magazine here.

In her essay, Looking at War, Susan Sontag writes: “Photographs of the victims of war are themselves a species of rhetoric. They reiterate. They simplify. They agitate. They create the illusion of consensus.” It’s a viewpoint that Vietnamese American photographer An-My Lê would probably agree with. And in her own work – far removed from the photojournalistic tradition of war photography, with its often graphic images of violence and suffering – she addresses many of Sontag’s same ethical concerns, encouraging us to question our perception of conflict and consider our own relationship to it. “I don’t document war and conflict per se. I photograph from the bleachers,” says Lê, “but I hope I address issues related to these subjects in revealing ways — whether I am photographing young American men re-enacting the Vietnam war in the woods of Virginia, or the Marines training in the high desert of California before deploying to Iraq or Afghanistan.

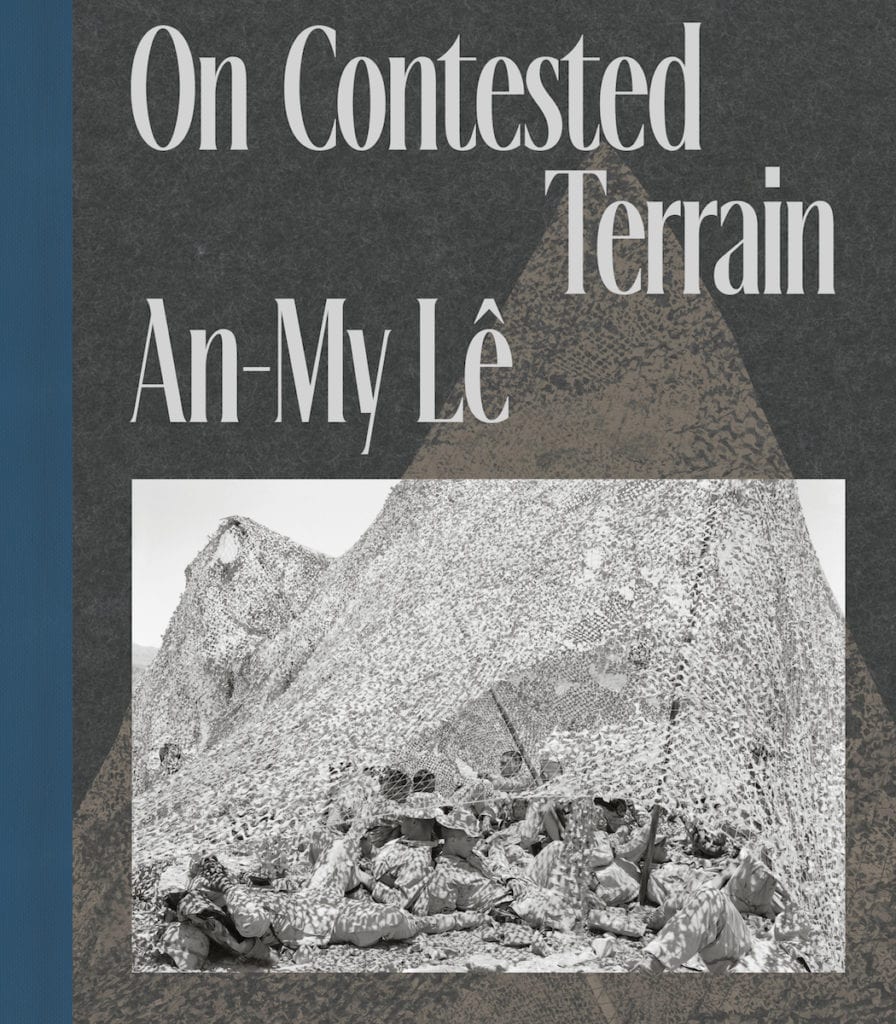

With her contemplative, large-format images, Lê muddies our understanding of conflicts past and present; she does not limit us to one line of understanding by thrusting straightforward depictions upon us. Drawing on historical representations of war, and the traditions of 19th and 20th-century landscape photography, she reflects on how the mythologies and contested histories of battles are played out in the places and memorials of the present. “Lê is not interested in providing objective truths,” explains Dan Leers, curator of the photographer’s retrospective, On Contested Terrain, which was due to run at the Carnegie Museum of Art until 26 July, but has been postponed due to Covid-19. A digital tour of the exhibition can be taken here, and an accompanying publication co-published by Aperture and the Carnegie Museum of Art is now available here. The show delves into her distinct approach, tracing its development across seven bodies of work, which span Lê’s almost 30-year career. “She is embracing uncertainty and ambiguity, and, in turn, allowing viewers to take a moment and step back; to think about their relationship to what is on show.”

The various series may touch on particular conflicts – the American Civil War, Viêtnam, Iraq, and most recently, the deepening social divisions in the present-day US – but common themes and approaches run through them. The use of landscape as a theatrical set on which to interrogate the conflict in question is central. “In Lê’s eyes, conflicts will change, and their players will change, but, in many ways, landscapes stay constant and bear witness to what has taken place,” says Leers.

Lê’s most recent series, Silent General, which previewed at Marian Goodman Gallery in London earlier this year, occupies a central part of the exhibition and epitomises her approach. “It is very much an extension of everything I had been working on previously, she says, “it is a response to what I feel is a war unfolding on the home front.” The ongoing project, currently comprising six fragments, jumps back and forth in time. It evokes darker strands of US history, such as the American Civil War and slavery, to open up questions about the present, both specific events and broader societal shifts, which Lê observed across the US.

Landscapes and sites of conflict remain central in Silent General, with Lê employing the American landscape as a canvas on which to address social and political tensions. In the work of Joel Sternfeld, Stephen Shore, and Robert Adams, Lê observed how the landscape can reflect the state of American culture, and translated this to her own practice, capturing spaces where contemporary issues can be seen and felt. The series evolved from photographs that Lê shot in the American south, which relate to the civil war that took place there. In 2015, film director Gary Ross invited Lê to New Orleans to photograph on the set of Free State of Jones, a Hollywood movie loosely based on the life of Newton Knight, a farmer and Southern Unionist who led an armed revolt against the Confederacy during the American Civil War. She photographed Ross’ recreation of the Battle of Corinth, during which Union general William Rosecrans led his troops to victory over a section of the Confederate army.

While making these pictures, Lê also observed the intensification of debates concerning the removal of Confederate monuments and memorials in the US. “The civil war happened during the 1860s, says Leers, “but with the recent drama surrounding things like confederate statues, or the US and Mexico border, Lê depicts how those historic conflicts continue to shape the landscape and our interpersonal relationships.”

The ascendency of Donald Trump and his open support of white supremacist and ultra Conservative causes played a large part in precipitating the project, which Lê hopes will call into question these viewpoints. Trump formally launched his presidential campaign in June 2015, and the following day, a 21-year-old white supremacist attacked the congregation of one of America’s oldest black churches in Charleston, South Carolina, killing nine African-Americans. “Leading up to the election, I felt that there was this rhetoric that became more mainstream: the simplification of issues that we face in the United States really started to bother me,” Lê reflects when I meet her in London, ahead of the opening of the Marian Goodman show. “The divisiveness that was building up was distressing.”

“I see conflict outside my doorstep today, so it feels very urgent”

On 12 August 2017, a 20-year-old white-supremacist and neo-Nazi drove his car through a peaceful protest against a white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, murdering one person and injuring 28. “That was the second thing that motivated the project, and gave me the confidence to continue,” she says. That same year Trump continued to push for a border wall between the US and Mexico to prevent further migration, a move that critics see as one attack line in a wider culture war being waged with an avalanche of divisive and discriminatory legislation, including an executive order that restricted immigration from seven majority-Muslim countries.“It was interesting to tie everything together, to talk about America’s history and assess the current situation. So I mixed project-based photographs with everyday scenes as the first presidential year unfolded,” she explains.

The photographer has always employed her work to understand conflicts to which she is connected, and that was partly the case with Silent General. “I see conflict outside my doorstep today, so it feels very urgent,” she explains. Her first two bodies of work, Viêt Nam (1994 to 1998) and Small Wars (1999 to 2002), both exhibited as part of On Contested Terrain, respond to her homeland, Vietnam, and the war that forced her to leave it. Lê was born in 1960 in the former South Vietnamese capital of Saigon and grew up amid the Vietnam war. In 1973, following the North Vietnamese invasion of the city, the photographer and her family evacuated to the US. Viêt Nam evolved from her experience of returning home for the first time in the almost 20 years it had been since she left. The desire to break through the fictional and sensationalised depictions of Vietnam in movies and the news motivated her, and similarly to Silent General, Lê wanted to work through her understanding of the conflict, and the relationship she has with it, through her practice and the Vietnamese landscape.

The photographer returned to locations from her childhood memories, which were often markedly different from what she and her relatives remembered. “Returning to Vietnam was a very emotional experience,” she reflects. “This led me to make photographs that reconnected me in tangible ways to memories I had of growing up in Saigon, to ideas about the more bucolic childhood my mum and her family had in the Hanoi area, while simultaneously confronting the reality of a contemporary Vietnam at peace but uncertain about its future in the global capitalist market.” Viêt Nam developed into a reflection on the “fog of war”, as Leers describes it: war’s ability to “scramble” and alter our perception. The project also marked the advent of Lê’s engagement with the subject of conflict, and her commitment to developing alternative ways to address it. In Small Wars, which came next, the photographer engaged with Vietnam again, but from a radically different perspective: participating in the activities of small groups of Vietnam War re-enactors based in Virginia and North Carolina. On a personal level, the experience enabled Lê to further interrogate her relationship with the conflict, particularly her perception of the enemy in this context. By playing various characters during the reenactments, the photographer endeavoured to open up her understanding of the “other”: both US soldiers and the Viet Cong.

With Silent General, Lê embarked on numerous road trips across the country, often seeking out sites of conflict, and photographed what she observed to make sense of what was happening. “It seemed that dramatic events were taking place almost every day, so travelling and finding a way to talk about those became very important,” she says. Walt Whitman’s publication Specimen Days, which Lê came across by chance, provided further inspiration. “It gave me a clarification of how to move forward. He was a journalist, so it is almost photographic in the way he talks about and describes moments and events,” she reflects. Written in 1882, short titled fragments divide the publication, throughout which Whitman reflects on his life, highlighting the influence of historical events on it — an entire section comprises poignant recollections of the American Civil War.

“It gave me a clarification of how to move forward. He was a journalist, so it is almost photographic in the way he talks about and describes moments and events”

The book’s structure also influenced Lê: “The fragments made me think about stringing together a series of pictures to say something; the whole evolution is not linear.” And, as with much of the photographer’s work, it takes time to unravel the Silent General, which feels as though it contains infinite meanings, to reveal the countless historical and contemporary references and the connections between these. “I do not want the pictures existing in a vacuum, and that is why historical references are important,” she explains of an approach, which is reminiscent of the use of history in Whitman’s Specimen Days. One image depicts the weather-worn statues of the secessionist generals Robert E Lee and PGT Beauregard, both generals in the Confederate States Army during the Civil War, housed in a temporary wooden container at a Homeland Security storage. The Confederate monuments represent the dark legacy of slavery and the ongoing issue of racism, which pervade the South, and indeed the rest of the US. By depicting the statues in storage, Lê strips them of their dignity and alludes to the wider movement disparaging this strand of history by protesting against monuments and statues that dignify it The themes of colonialism, migration, and displacement extend throughout the series and across time: another of the project’s fragments comprises images of female border patrol officers positioned either side of a transnational bridge spanning the border between Mexico and the US.

Read together, the images, many of which depict quintessential scenes of American life in exquisite colour — a small, white church nestled among vast expanses of rolling meadow, a tarmacked street lined with industrial warehouses — are the antithesis of news photography. Shifting between landscapes and social portraiture, the photographs do not document specific events. Instead, they contain interweaving narratives that span decades, which interrogate the US and its political history, particularly in the South, along with multiple other issues such as identity, racism and immigration.

The instantaneousness of news photography is absent from all of Lê’s work, which she creates using a large-format camera. The effect is powerful, imbuing her photographs with a sense of stillness and grandeur. The photographer often shoots from an elevated perspective, affording viewers the space to contemplate what is in front of them. “I want to keep the viewer engaged long enough so that they will start being engaged intellectually as well,” she says. This is exemplified in 29 Palms (2003-4), which is also on show as part of On Contested Terrain, and which Lê began following the invasion of Iraq in 2003: “I was distraught at the idea of another Vietnam repeating itself,” she explains. The photographer initially applied to embed as a photographer with deployed troops, but, with all of the positions filled, she visited Twentynine Palms instead — a Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center nearby Joshua Tree National Park in San Bernardino County, California. Her striking black-and-white images capture marines in training for deployment to Iraq against barren swathes of desert. The photographs hold our gaze and exude a sense of the magnitude of war, and the overwhelming experience of being entangled in it.

Lê’s work draws us in with its “complicated beauty,” as she describes it, explaining the discordance between her images’ aesthetic appeal and their darker, underlying narratives. “I want people to enter into a picture and have a complicated physical and experience,” she says, which is also facilitated by the ambiguity of the photographs, both individually and in series. However, the work is as much for Lê as it is for us, allowing her to question and draw connections between things in an attempt to understand them. This creates multi-layered photographs that take time to untangle. As Leers observes: “There are often more questions asked than answered,” and that is what makes Lê’s work so crucial – it considers and meditates upon the impact of conflict, reaching across time and space, to explore “how it continues to shape our cultural narratives”.

anmyle.com

An-My Lê: On Contested Terrain, the first comprehensive survey of An-My Lê’s oeuvre, is co-published by Aperture and Carnegie Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh.