Creating a legacy

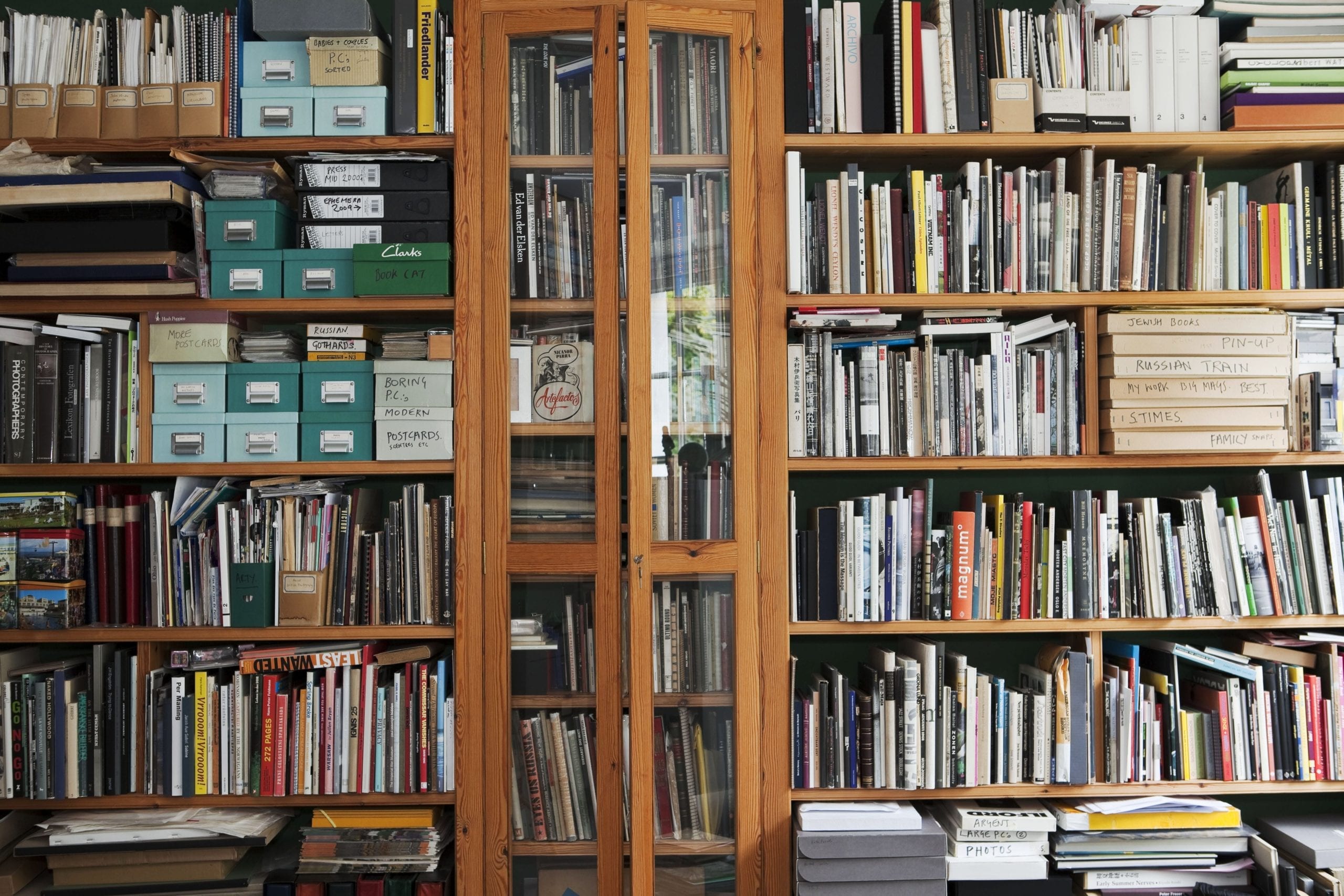

Since the first two volumes of The Photobook: A History came out, there has been a spate of books about photobooks. “We are not the only people contributing to this forum,” Parr says, pointing to a shelf on the subject. “Many other books have come out; specific books about Holland, Switzerland, Latin America, Germany, and many small ones like Finland and Denmark.” To a large extent, the publication of these books was made possible by the interest generated by the first two volumes of his series. “We knew it would be a contribution to the ongoing interest in the photobook, but we had no idea it would be so successful both in terms of the numbers bought and in terms of the impact, and then on the prices of books [as they became more collectible],” says Parr. “So now people blame us for that. You can’t win, really, can you? Since then, despite the internet, there’s never been more publishing activity, or more interesting books come out.”

This impact on prices can also be seen as a reflection of the increase in how seriously photobooks are taken. “Price, in one sense, is a vindication of the process,” says Parr, “because prices are determined by supply and demand. Of course, if books become popular the price goes up, and if they’re in Volume III, the same happens. People are desperate to get hold of Volume III, so they can start buying up the books. I could do that but I can’t be bothered. Occasionally, I buy an extra copy if there’s a particular book I like, but not to the extent that it would be like insider trading.”

I mention the rumour that he bought 35 copies of The Afronauts by Cristina de Middel and he laughs. “That was annoying because it was entirely wrong. That was Sean O’Hagan [photography critic at The Guardian], but I’ve got him to correct that. I don’t know where he got it from. I think he wanted to hear that. We pull each other’s leg about it so it’s very funny. And that’s the sort of stuff that goes around. People love that. It’s a good story. Who cares if it’s true?

“The truth is, I met Cristina very early on and I said to her, “This is a great book. Do you realise how good it is?” I may have bought three or four from her, and often I will do that with a book I really believe in, just because they are a good thing to have. It’s worth supporting someone even though these books become highly sought. I told her it was a great idea, with good design, and then everything fell into place perfectly. This book has become legendary in a very short period of time and launched the career of an otherwise unknown photographer. Her problem, of course, is what to do next, because when you do something that good it’s difficult to follow up. But she’s smart so she’ll be fine.”

Intricate design also extends beyond the page to the mechanics of the book in the latest photobook history – from the multi-volumed slipcase editions of Paul Graham to the boxed design of Peng Yangjiun and Chen Jiaojiao, to the wire-bound simplicity of Ricardo Cases’ Paloma al Aire. The most complex design award goes to David Alan Harvey’s Based on a True Story, a book with a loose-leaf interactive narrative that is quite a sight to behold. And although making photobooks can be incredibly expensive, the first two volumes from Parr and Badger have also legitimised cheaper papers, bindings and production methods, and this is apparent in the number of recent books inspired by design techniques they illustrated.

“When people make a good book, you obviously see that design copied,” says Parr, who isn’t concerned. “It’s all good. It’s the same with photography. The language of photography is constantly evolving, and photographers have an impact on that. There are the photographers who people notice, who have a vision. Who those photographers are in the third volume is difficult to say. There will be books rediscovered. For example, do you know Gian Butturini’s book on London? It is entirely unknown in the UK, and it will become better known here. There was a whole wave of photographers in the 1960s who came from abroad and photographed Swinging London. British photographers weren’t doing it.

“There are photographers such as Rinko Kawauchi and more recently Lieko Shiga, and they have had an influence and have become part of the language of photography. But funnily enough, the biggest woman photographer in Japan is Ume Kayo. She’s part of the social networking generation and basically makes Facebook pictures with an edge. She’s a really interesting woman and outsells everybody in Japan, and yet she’s not known at all outside of her home country. Because everybody’s very slow you see. Curators are very slow,” says Parr, the suggestion being that curators like to stay in their comfort zone and stick with what they know.

Another change is the way photobooks have become a part of exhibitions – he cites the Daido Moriyama + William Klein joint exhibition at Tate Modern in 2012, in which the photobook was central both to the relationship between the photographers and the way they disseminated their work. “In the vitrines, there were 50-odd books [many of which Parr loaned from his collection] that give a bigger picture of why these two people are so important. That’s something that has really changed. Museums now understand the relevance of the book and will include them in exhibitions… and that’s a very dramatic and positive shift because you can see how the work was published and disseminated.”