‘It is essential that this important exhibition is seen by as many women as possible. To do this we need money – to make it fit to travel all over Britain. Please help and send donations to:- “The Hackney Flashers Collective” who took all the photographs and organised it.’

Written in red marker pen, the appeal appears on a poster made in 1975 by socialist-feminist collective The Hackney Flashers. With their travelling exhibitions, Jo Spence and other members created influential agitprop materials as a way of confronting social prejudices.

Their black-and-white prints – of women at work in factories; female machinists hunched over sewing machines; a mother holding a saucepan over the stove and a baby on her hip – helped campaign for equal pay in the workplace and better childcare provisions.

“They wanted to operate in society and not as part of the art world,” says Elena Crippa, who curated the retrospective of Jo Spence’s work at Tate Britain.

Using the flash of the camera as a pun on the revealing nature of photography, The Hackney Flashers sought to expose and abolish outdated stereotypes. A ground-drill for the mind, the camera became the most powerful tool with which the collective, unconcerned with the lofty heights of the art world, could create dents in the socioeconomic world of the people.

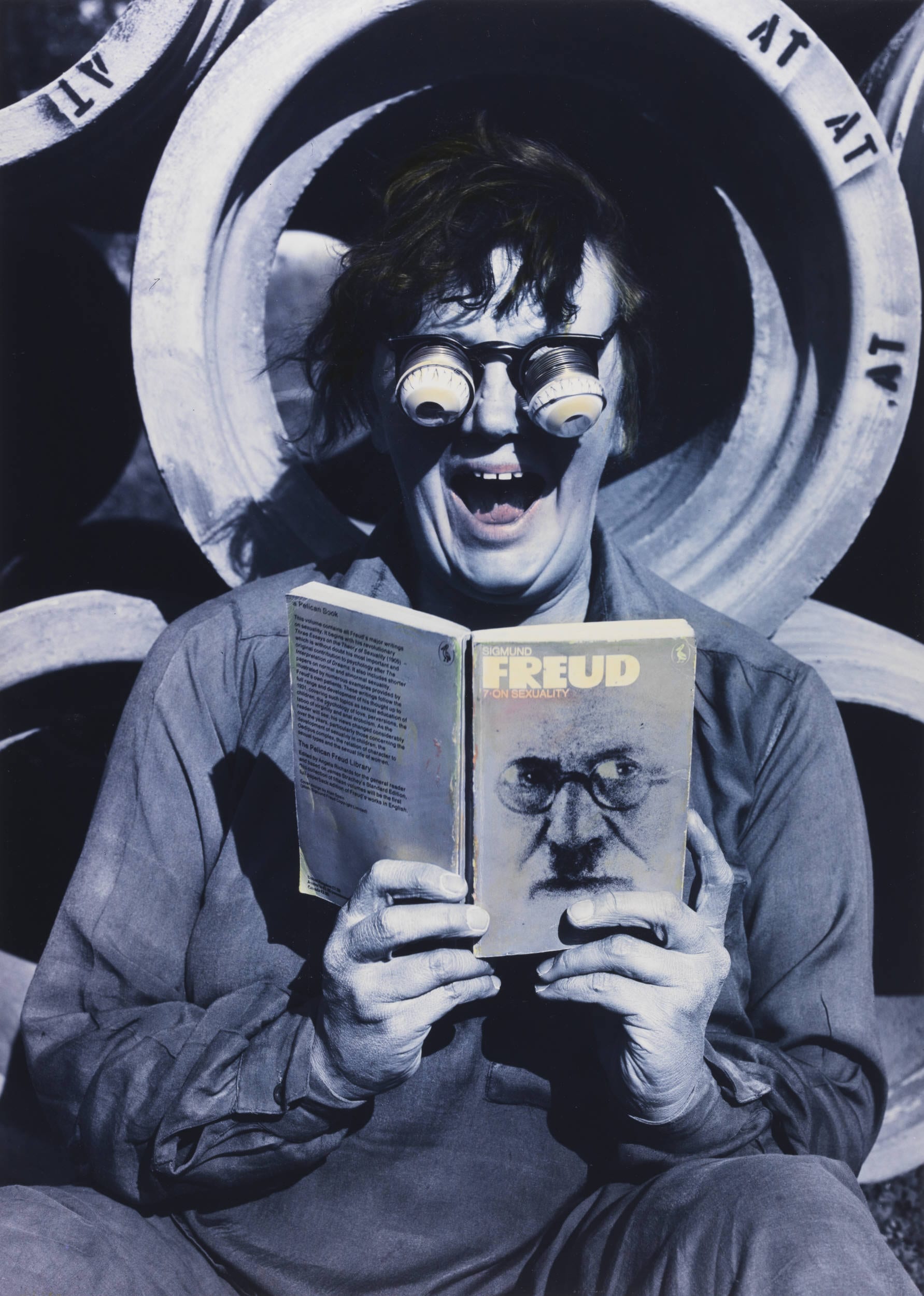

For The Flashers, the message preceded the form and the same can be said for Spence’s personal work. Personal in every sense of the word; her self portraits are as revealing as fresh cuts of meat. Laying bare the female body, Spence opened up a dialect of identity politics that few of her contemporaries dared to whisper. Intimate, humorous, vulgar and honest, her iconoclastic portraits challenge notions of sexuality, body politics, gender and disease.

Spence first entered photography through a comparatively conventional route: after taking a Kodak training course she opened a studio providing photographic services for weddings, passports, family portraits and actors’ mugshots. By 1978 she left behind the vacant smiling faces of commercial photography and turned the camera on herself.

Using role-play and subversion, Spence played a panopticon of roles that attempted to liberate women from outdated stereotypes, as well as her own personal, emotional and medical self.

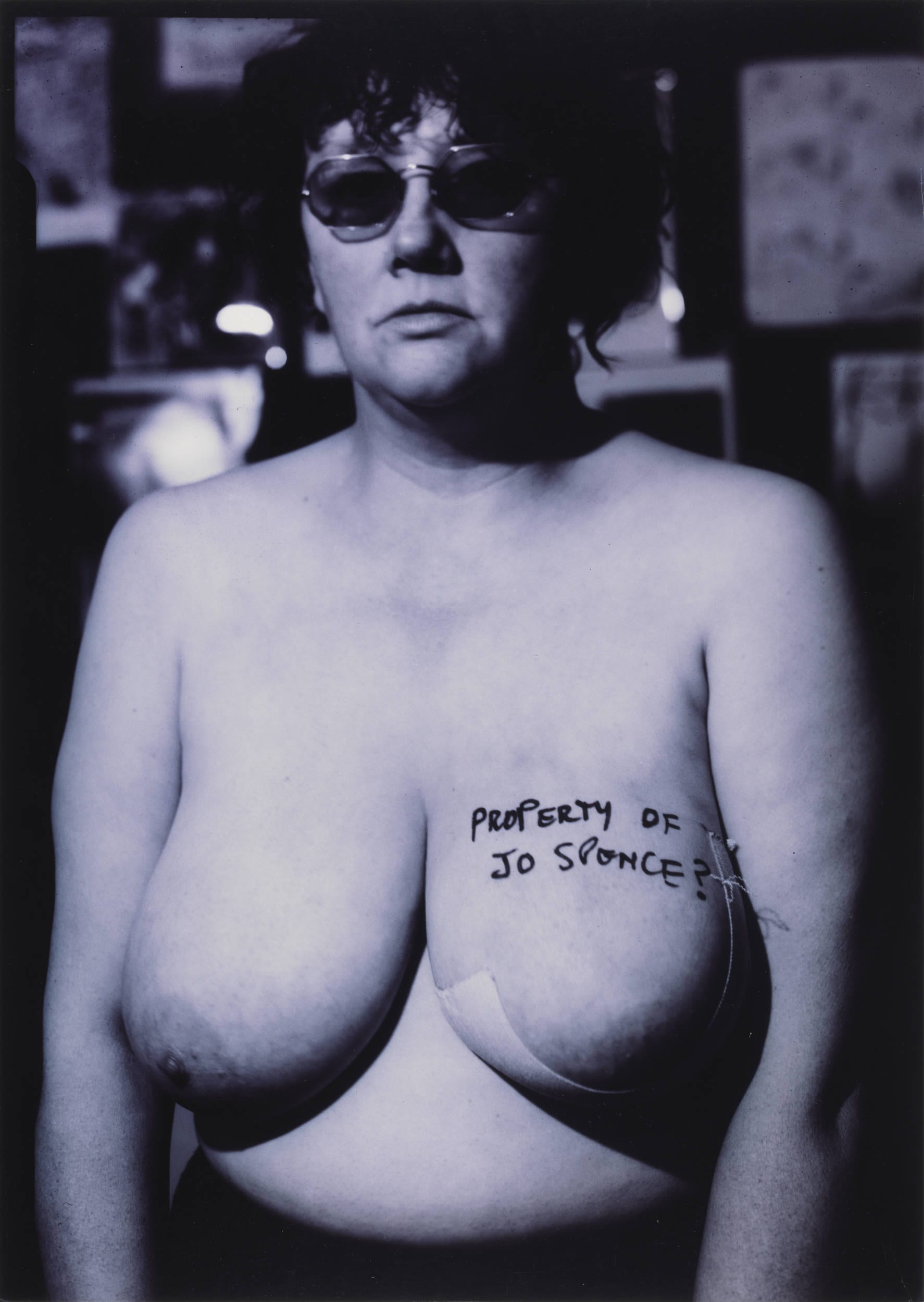

In 1982 Spence was diagnosed with breast cancer and began to explore the politics of disease through her work. The Picture of Health? became a kind of research project that attempted to document her journey through illness and treatment while interrogating the ‘medical gaze’. One portrait shows her topless, staring at the camera with a bandage under her left breast and the words ‘Property of Jo Spence?’ scribbled in black pen above the nipple. She took the photograph with her into hospital as ‘a pre-operative talisman to remind myself that I had some rights over my own body.’

Another striking image from the series shows Spence standing in profile with her breast sandwiched between a mammogram. “There was no response to the exhibition” says Crippa, “and Spence felt a terrible sense of isolation. As she has stated, nobody knew what to do with the work, because there was not yet a vocabulary to discuss work that addressed issues of identity.”

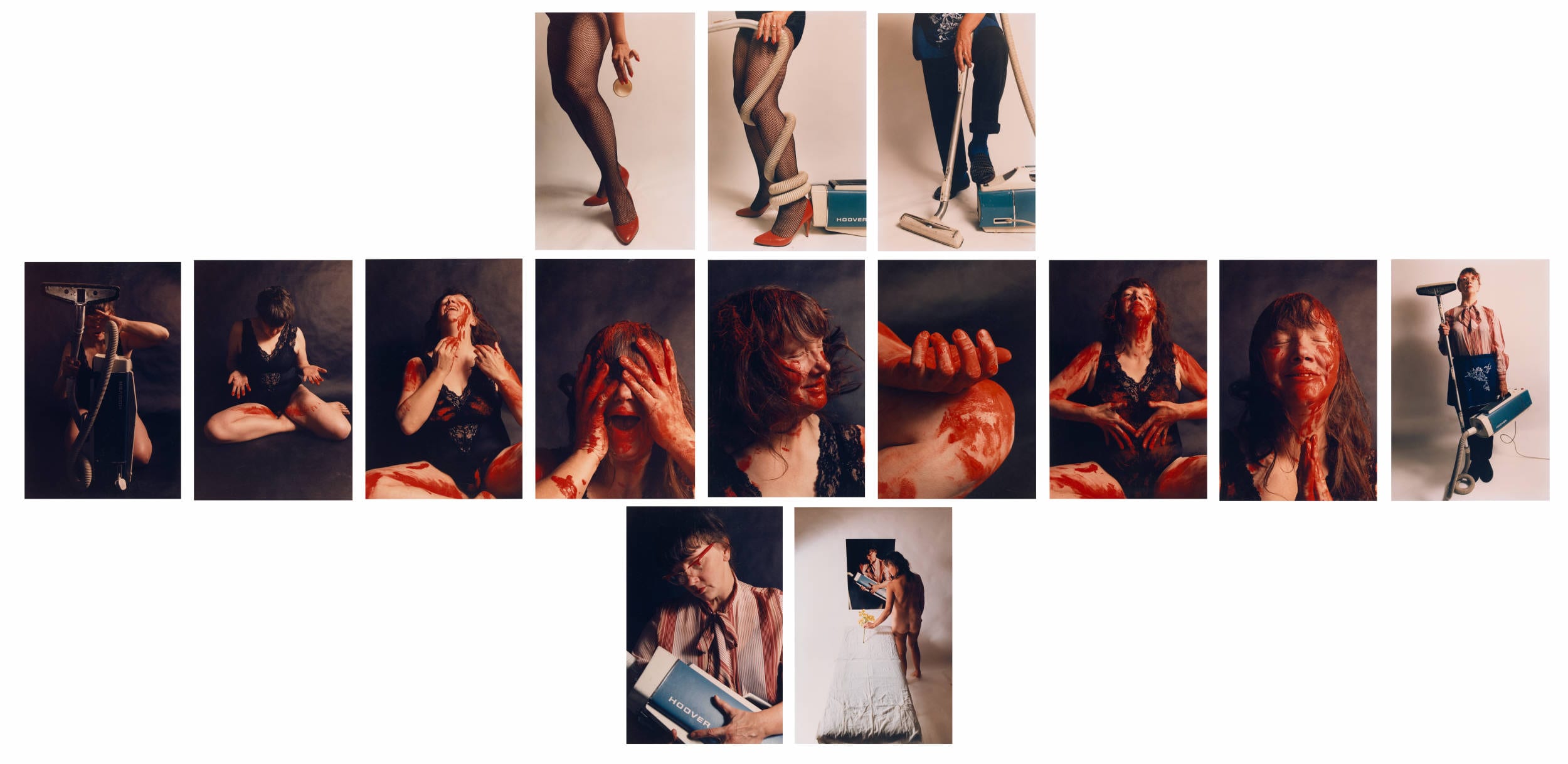

For Spence, this often crude documentation was a necessary journey in reclaiming her body from the illness and a form of phototherapy that she would later return to. Collaborating with artist and therapist Rosy Martin, in 1984 a series titled Libido Uprising, shows Spence in the guise of mother and housewife – slipping on a pair of fishnets and transforming both into a form of fetishised, hilarious eroticism.

With a prop cupboard full of magazines, diaphragms, fishnets, hoovers and period blood, the duo took those stifling stereotypes that attempted to trap women and spun them crucially on their pretty heads. Exploiting the emancipatory potential of photography, Spence continued to prize open the discourse around body politics. Like a women walking through a hall of mirrors, her timely portraits reflect the surreal and the painfully real aspects of identity that remain relevant today.

As part of the BP Spotlights series, Tate Britain will showcase key works by Jo Spence (1934-92). Curated by Elena Crippa, the display will take place from Monday 19th October – Autumn 2016.