Stretching deep through the spine of California’s Central Valley is Route 99. Once the primary north-south highway on the West Coast of the US, it has now given way to the much larger Interstate 5. As a result, a string of towns in the 60-mile-wide, 450-mile-long route have been forgotten by the majority of travellers on their way to San Francisco or Los Angeles.

Nestled deep in this dust-filled, insufferably hot region are the sites of Katy Grannan’s The Ninety Nine and The Nine. The title of the series of portraits, The Ninety Nine, references Route 99 and the small towns along its reach. The Nine is the title of a series of accompanying large-scale, black-and-white landscape photographs, as well as an upcoming film. This title refers to South 9th Street in the town of Modesto, which is considered to be one of the most dangerous roads in the region. It is also the place where many of her subjects reside.

The landscape of the Central Valley is empty, physically expansive and physiologically charged. The valley is flat and flanked with rolling hills and low-lying mountains to the east; the towns in the area are isolated, and populated with the familiar markers of roadside motels, chain restaurants, car repair shops, barbed-wire fences and desolate roadways.

Many of the towns along Route 99 have come to represent the ideals and bountiful possibilities of America’s westward expansion gone terribly wrong. The economic downfall of the past few years has not been kind to them and, as a result, a sense of desperation permeates the dry air. This region has the power to make anyone feel they are alone, ignored, anonymous and forgotten.

“DO I REALLY MATTER? ONE WAY OF ADDRESSING THIS, OR ACKNOWLEDGING VALUE, IS TO MAKE A PHOTOGRAPH AND CREATE SOMETHING THAT HAS A LIFE OF ITS OWN.”

Poverty, adversity and despair are not new to California’s Central Valley, however, as Dorothea Lange’s photographs of the same region, produced during the Great Depression for the Farm Security Administration, show. Quality of life has simply not changed for many of the people there. Like Lange’s work, Grannan’s series highlight the plight of the poor and forgotten, but conventional documentation is not necessarily her goal. Instead, her portraits give way to metaphors and universal archetypes – at once a self-portrait and a collective portrait, they become pictures of all of us.

Invisible people

Anonymity has been a recurring theme for Grannan. Her portraits have consistently carried the title Anonymous, followed by the location in which the subject was photographed. For Grannan, it’s a title that emphasises the predicament of society’s neglected. “The portraits are titled Anonymous, not because I am trying to conceal the subjects’ identity, but because I want to underscore the notion that they are often overlooked and forgotten,” she says.

“I’ve always photographed people, in part because I feel anonymous. The impulse often comes from a place of feeling overlooked, and perhaps this is just an existential question. Do I really matter? One way of addressing this, or acknowledging value, is to make a photograph and create something that has a life of its own.”

In fact, the question of shared experience shines through in Grannan’s series of portraits, which can be read as deeply personal – yet universal – questions about existence. “Throughout the whole process I’ve been thinking about these elemental issues of God and beauty – ‘Where does one find joy? What constitutes happiness?’ – all of these things that are shared common experiences and questions,” she says. “Where is God, or where is that loving presence in a place that is so bleak? And, why are some people subjected to it to such a horrific extent and others practically untouched by it?”

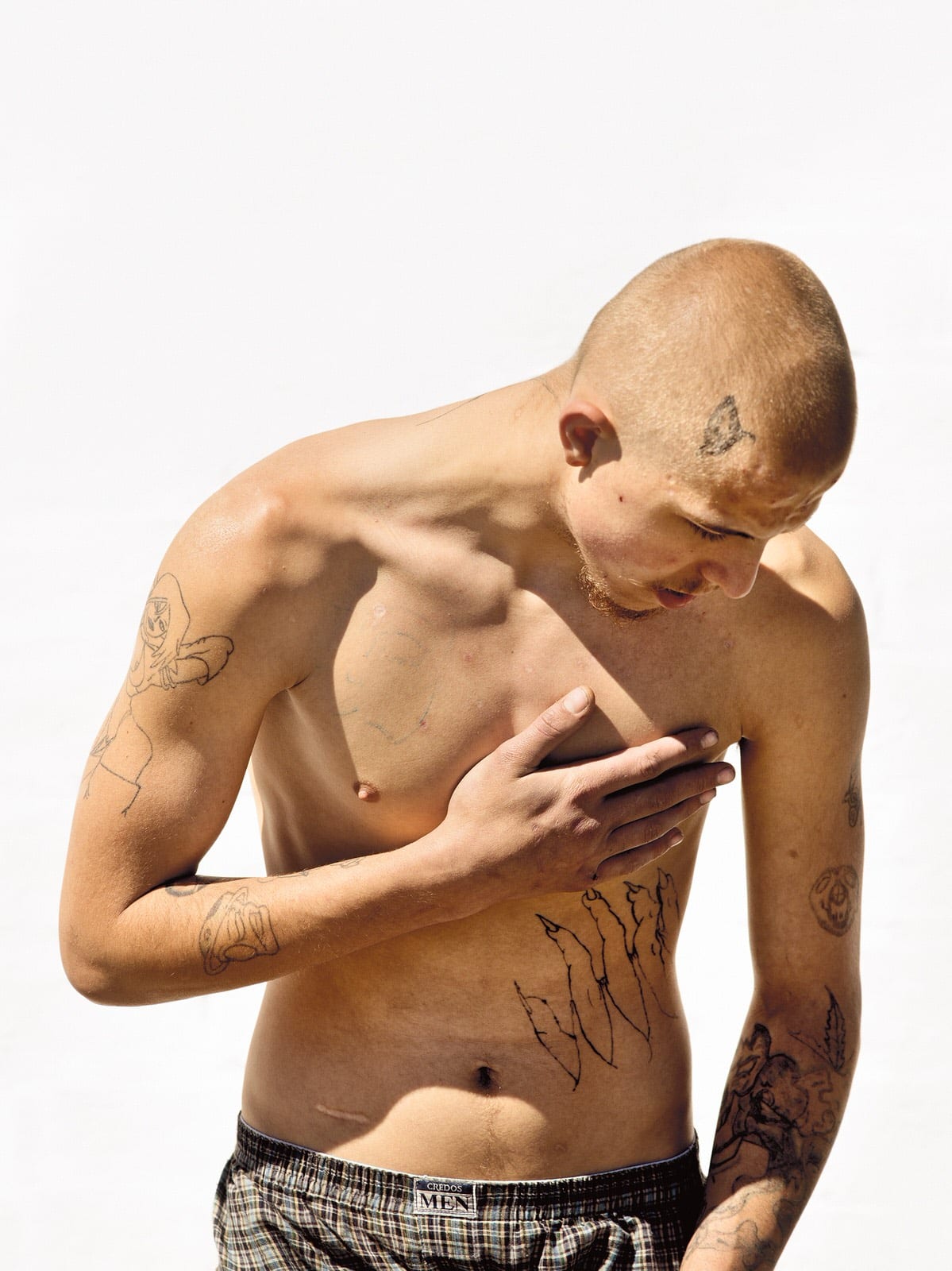

In The Ninety Nine Grannan digs deep into communities most choose not to see, showing people steeped in economic desperation, often engaging in drug use and prostitution, tucked away in forgotten towns, under bridges, in alleyways, and in cheap motels. Grannan brings her subjects out of the desolate shadows and into the stark California light, rendering them with brutal, matter-of-fact detail.

Many of the portraits in her previous series, Boulevard, examine the role of fantasy and delusion as a mechanism for coping with reality; in The Ninety Nine a stark realism suggests that tomorrow will not be any better than today. Her subjects take life one day at a time, and Grannan is able to depict their full range of emotions, from hopelessness, longing and fear to pride, joy and affection. Quietly present over long periods, she has been able to build trust, and as a result, individuals who are often guarded become open, willing to express their most vulnerable states in front of the camera.

“The relationships I have built with the people I am photographing have become much closer to really great friendships, as opposed to some of my earlier work, which felt more like a one- night stand,” Grannan says. “In the beginning, everything is perfect and no one disappoints you, but as time progresses, my relationships with the people I am photographing become much more involved and very long term.”

One of my conversations with Grannan took place just after she’d been to a prison in the Central Valley, for example – Inessa, one of her closest friends and a recurring subject in her photographs and film projects, was being released after serving a nearly two-year sentence. Grannan, who met Inessa through photographing, has spent years visiting and writing to her, and has become one of the only consistent and dependable factors in her life.

But while drama is plentiful in her subjects’ lives, and while tragedy and vulnerability are apparent in the portraits, a strange sense of beauty and heroism also emerges. In Anonymous, Modesto the subject is captured at close range, the focus falling on her eyes and becoming soft around the chin and mouth. The scars of fear and worry are evident in the deep crease of her forehead, yet her eyes remain fierce and piercing, her gaze pointed slightly upward and to the distance. Her eyes speak volumes. The subject’s distress is not fleeting but confidence remains, at least for the moment, and her look evokes a sense of willingness to face the future.

Many of Grannan’s subjects find solace in companionship, in knowing that, while they may feel overlooked, they are not alone. This is demonstrated in the double portrait, Anonymous, Bakersfield, in which a middle-aged man, cigarette in hand, is clutching a young girl, arms lovingly wrapped around one another. The man, shirtless and tattooed, is looking into the merciless light, while the young girl looks innocently off into the distance. Their embrace brings a sense of intimacy and comfort for the man and the girl, and for Grannan herself. While sadness is still evident, in this second the subjects and the photographer are at peace, together.

From a distance

“WHAT DOES IT FEEL LIKE TO JUST STAND BACK, TO NOT HAVE TO HAVE A CONVERSATION, OR BECOME FRIENDS, WITH VIRTUALLY EVERYONE THAT I PHOTOGRAPH. WHAT WOULD THAT BE LIKE?”

Standing in stark opposition to the colour-saturated, contextually reductive portraits in The Ninety Nine is the series of rich, quiet and expansive black-and-white landscapes. Grannan has utilised the landscape in the past but often as tightly cropped backgrounds for her full-frame portraits. In The Nine, the landscape engulfs the individual and reveals more about the qualities of place. Kings County provides the greatest distance for the viewer, for example, illustrating an isolated town far on the horizon.

When I asked Grannan why she wanted to show landscapes at a such distance, she explained, “Because [the subject’s] life gets so entrenched and intertwined with mine – so many of my texts and phone calls are from these people that I know, initially through photographing – I was frankly getting exhausted.

“I have three kids, and I was asking myself, ‘Am I neglecting my children for this community in the Central Valley?’ That was part of the reason that I started making these landscapes that were at more of a distance. I started to ask myself, ‘What does it feel like to just stand back, to not have to have a conversation, or become friends, with virtually everyone that I photograph. What would that be like?’”

The mental remove Grannan was seeking becomes evident as the physical distance simplifies the landscapes, bringing a sense of beauty, peacefulness and order to some difficult places. The subjects’ tumultuous lives collide with the tranquillity of the open space, creating a captivating tension between person and place.

They are nearly always depicted engaging in mundane tasks, as the image titles suggest – Kiki Pays Debt, Inessa Alone in Shiva’s Courtyard and Deb Soaking Wet – but despite, or perhaps because of, the everyday nature of the scenes, they open up to a much wider context. While the portraits rely on the weathered physicality of her subject’s body and clothing, the landscapes provide context through which to understand her subjects’ daily lives. The extreme whites reflect the same harsh California light found in the portraits, light which rakes across the pictorial space and is punctuated with deep, dark shadows.

The bright whites and rich tonal range recall many familiar pictures by Robert Adams, but here Grannan allows the bleak spaces to serve as metaphors for her subjects’ mental landscapes. In Inessa Waits Near South 9th Street, for example, a familiar character stands with her back turned to the viewer, her shadow looming just behind on the glowing white wall. The subject is static and incredibly stoic, the picture demonstrating the universal mental struggle inherent in anyone making a choice that they know will have disastrous consequences. The shadow becomes her demon, slowly following her through the streets.

“I AM CONSTANTLY LOOKING AT MY OWN MOTIVES AND PREOCCUPATIONS, ASKING MYSELF, WHY AM I ATTRACTED TO THIS KIND OF PLACE, OR STORY, OR PERSON?”

Grannan recalls a childhood friend who became a heroin addict and prostitute – “It’s funny the way life turns out,” her friend told her. “I always thought you’d be more like me and I’d be more like you.” At the time Grannan also believed their roles could have been reversed, but has since given herself more credit for her positive decisions. Through creating this work she has been able to confront her fascination with her subjects; she feels they are “her people”, since they have all been willing to tempt fate – unfortunately, often with dire consequences.

The Nine and The Ninety Nine work together to illustrate the failed potential of so many communities, and in doing so reach out well beyond California’s Central Valley. The anonymity of the people and places depicted suggests a universality of existence, allowing the viewer to place him or herself among the narrative trajectory, and by rendering those so often overlooked in such relentless detail, Grannan shows the thin line that separates one from another.

It is easy to dismiss these anonymous individuals while driving through dwindling towns, under urban overpasses and down dark city streets; Grannan’s pictures show that under different circumstances anyone can fall into a life of desperation. Light can penetrate even the darkest of places and show beauty, all we need to do is be willing to look. BJP

Find more of Katy’s work here.

First published in the April 2014 issue. Subscribe to the British Journal of Photography and have the best stories in contemporary photography delivered to your door or device every month.