Following the breakout success of Easy Rider, Hopper was hot property in Hollywood and had finally secured funding for The Last Movie, a long-gestating passion project about a stunt co-ordinator, played by Hopper himself. “He was emerging as a rebel, a talent, a film maker,” Schiller says of his subject, “A brilliant man for his age.”

Easy Rider was an award-winning portrait of counter culture that at the same time managed to storm the international box office. In a 2010 retrospective of his career, The Washington Post called Easy Rider “a movie that would redefine film on nearly every level,” praising it as “a cinematic symbol of the 1960s, a celluloid anthem to freedom, macho bravado and anti-establishment rebellion.”

The pressure to find success in his follow-up effort led to Hopper to scrap his entire first cut of The Last Movie film in favour of a more avant-garde edit. The version he eventually released sought to break new cinematic ground by following a disjointed narrative, and employing unconventional filming techniques such as jump cut and rough edits. American Dreamer follows Hopper as he tries to complete post-production.

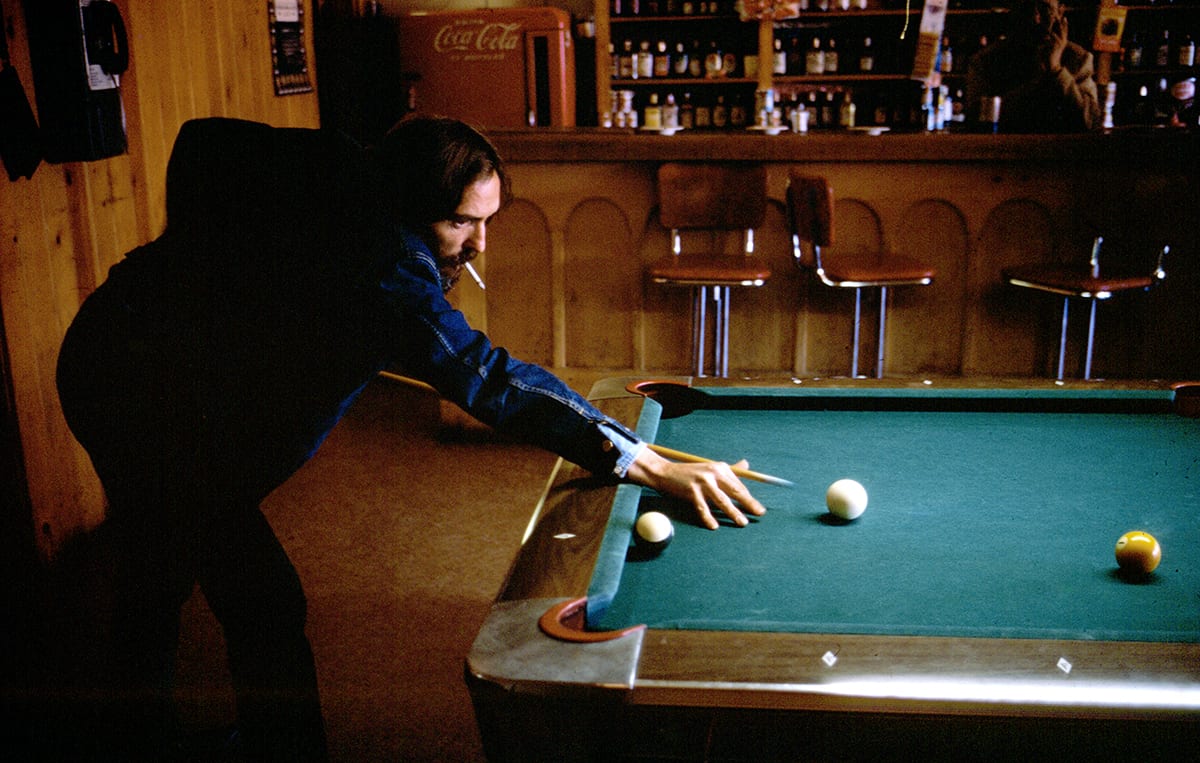

During the filming of the documentary, Schiller had his assistant carry a stills camera at all times and would hand Schiller the camera when Schiller wanted to capture a moment on camera. These photographs from co-director Lawrence Schiller show Hopper looking relaxed and pensive in New Mexico. In truth, Hopper was battling a drink and drug addiction that would last fifteen years.

Whilst praised in some critical circles, The Last Movie bombed at the box office. Hopper’s career, both as a director and as an actor, suffered accordingly. He wouldn’t truly surface again until the early 80s, carving a niche for himself playing pathological sociopaths in films such as David Lynch’s Blue Velvet, Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now and more commercial studio fare of the 90s such as Speed and Waterworld.

Little-seen, American Dreamer is now being screened in the UK alongside a series of behind-the-scenes photographs by co-director Schiller.

Developing a successful career as a photojournalist in the 1960s, Lawrence Schiller contributed to Life magazine, The Sunday Times and Time Magazine, with several covers and essays attributed to his name. But in 1970, general circulation newspapers in US were in sharp decline with the rise of television and, like many photographers, Schiller found himself looking for a new profession. “I decided to start to make films, documentary films,” Schiller tells the BJP.

Schiller had already had a taste of movie-making, having shot the montage stills for George Roy Hill’s Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, starring Paul Newman and Robert Redford. “I was becoming known as a film doctor but I wasn’t satisfied with that,” he says. “I wanted to become a film-maker myself.”

After experimenting with several documentary shorts, Schiller had hoped to make a documentary about Paul Newman with creative partner Kit Carson.

But when the star of Butch Cassidy declined the offer, Schiller and Carson approached Dennis Hopper, whom Schiller had met when shooting stills for Cool Hand Luke.

American Dreamer, their resulting film, might have been a glimpse into the psyche of a troubled artist caught between artistic success and commercial failure. What soon became apparent to Schiller, however, was that “it was impossible to do a documentary on Dennis Hopper.”

The cameras at the time required extensive lighting rigs, the scale of the surrounding film crew making filming inevitably obtrusive. “If you’re a professional person,” Schiller says, “you can’t act natural.” Hopper is evidently aware of the camera. He’s performing, playing a version of himself. As a result, the film plays out as a self-conscious documentary.

Schiller cites the opening scene as an example of how fact and fiction where blurred. In the film, the camera crew arrive to at Hopper’s apartment to find Hopper dishevelled and naked. He welcomes them in and walks straight into the bathroom and steps leisurely into the bath. The scene was staged by Hopper and the film-makers. “As a photojournalist, I knew how to introduce characters,” Schiller says.

Hopper refused to see the film as it was being edited, leaving the filmmakers to make their own movie. Yet he was aware of how he could use the film to promote his image as a renegade film-maker and actor. “Dennis was a very smart business man,” says Schiller. “He realised he needed to build a brand.”

Hopper agreed to the documentary on the condition it was screened alongside his own film, The Last Movie. Elsewhere, it was contractually agreed that it could only be screened at colleges and universities where Hopper was aware he had emerging audiences. “He used it to reach people he couldn’t reach in any other way, reaching people who maybe had never seen Easy Rider,” Schiller says.

Schiller has since donated American Dreamer to The Walker Arts Centre in Minneapolis, Minnesota, with profits from the film going towards preserving the work of other film-makers. Despite its recognition as a historial document of one of the great movie star’s life, Schiller sees the film largely as an experiment in film-making, a learning process.

“I was playing. I was learning,” he says, revealing he was much more concerned with learning the art of story-telling through film than of making a documentary about the real Dennis Hopper. American Dreamer would be Schiller’s film school, the beginning of a career that would see him go on to direct seven motion pictures and miniseries for television, including The Executioner’s Song and Emmy-award winning Peter the Great.

Even now, when the film is screened at colleges, the film-maker reminds students that the film isn’t merely a documentary about Hopper. In his own words: “This is a portrait of Larry Schiller.”

American Dreamer in cinemas now and released exclusively on MUBI this Friday.