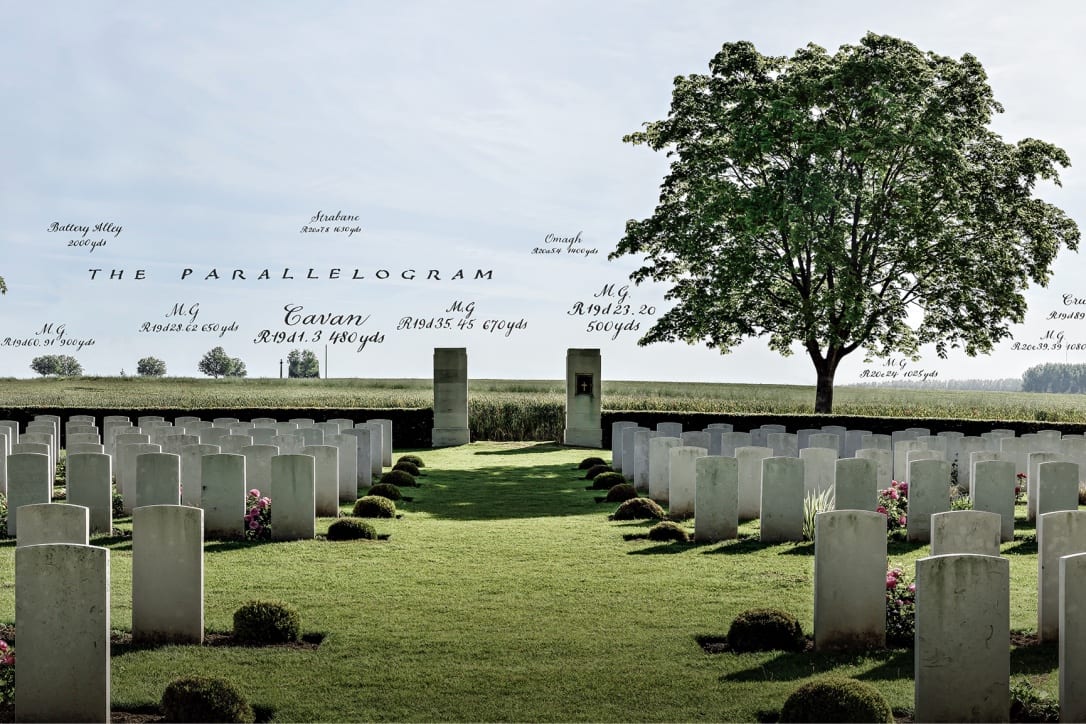

The tragic ironies of the Somme (its opening day most of all) continue to cast their spell. Visiting the scene of the battle today, one discovers the ironies persist: where once witnessed the start of the greatest battle in history and the greatest human suffering our country has ever known, one now finds an empty landscape of mature deciduous woodland and quiet rolling farmland. Only the cemeteries and memorials betray the history of these unassuming ‘foreign fields’.

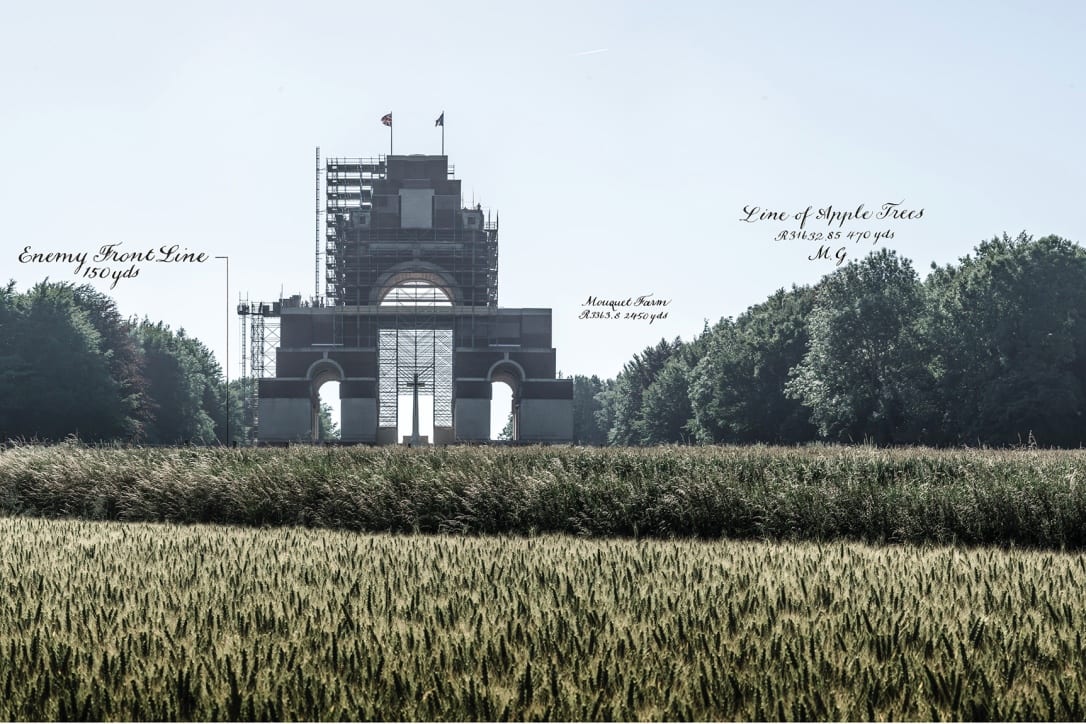

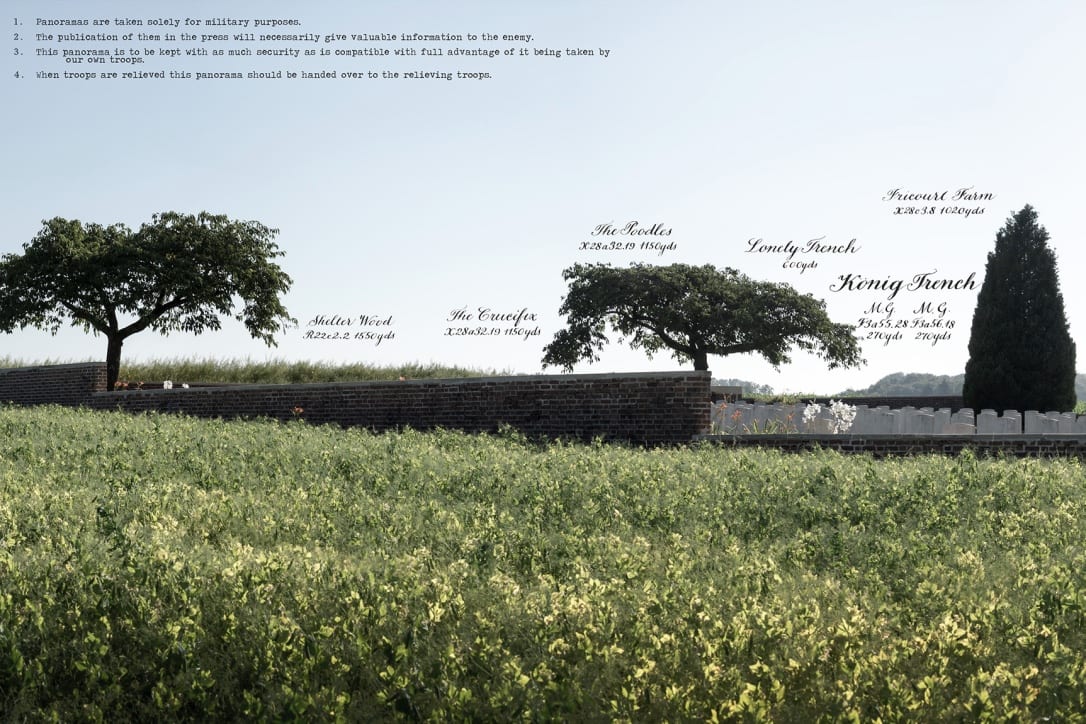

The origin of the Zero Hour Panoramas lay with my discovery some years ago of the battlefield panoramas created for strategic purposes by the military of the time. Annotated by hand with the landmarks of the German positions (invariably christened by the British soldiers themselves), they were used to give officers a panoramic field of view of the battlefield from the safety of their dugouts. The finished panorama included the location of the photographer, the date, the total field of view in degrees, the direction the camera was facing and a scale of degrees to inches. They were also, like almost all practical documents of the time, very handsome.

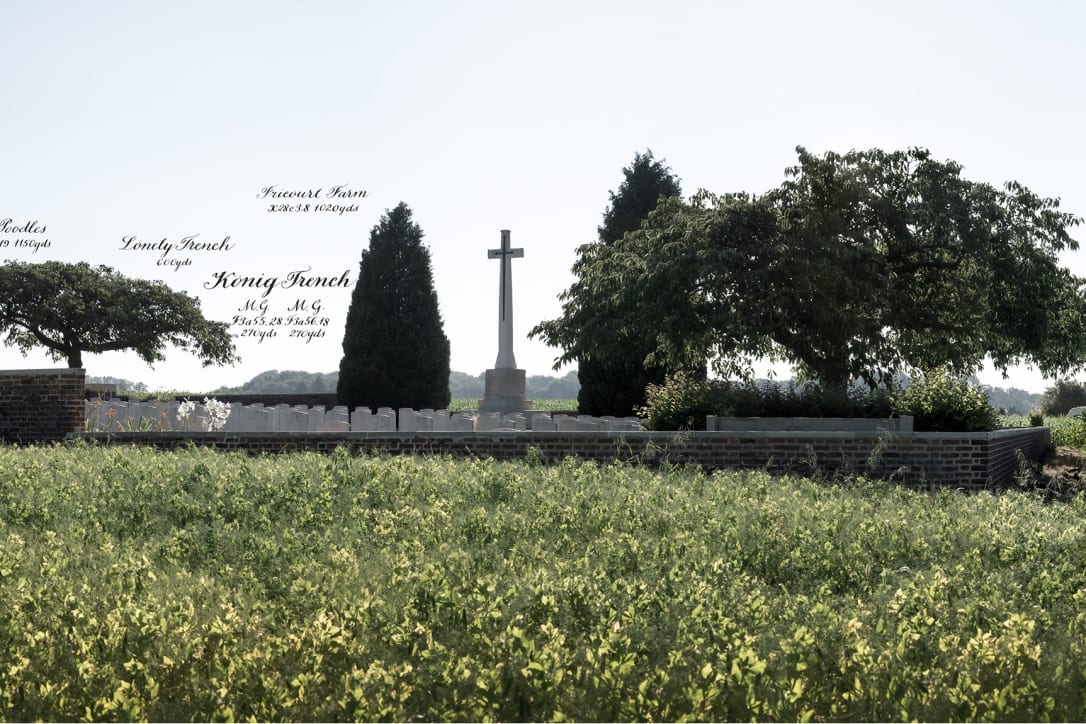

My discovery gave me the idea of borrowing their approach as a device to juxtapose the benevolent-looking now with the doom-laden then. Where now are rich fields of corn we can see were once German trenches. Where now stretch the wire fences of a French smallholder’s enclosure once stretched the barbed wire of the German front line. Where now are grazing cows were once German machine gun positions – the same machine guns responsible for so many of the crosses and graves that appear in the photographs. Overlaying the authentic official military stamps and annotations (exactly – and as accurately – as they might have been set out by the Royal Engineers of the eve of the battle) also allowed the explanation of the picture to be part of the picture. If you look at each picture closely enough, it reveals (as well as authentic, technical information) when it was taken, where it was taken from and therefore why it was taken.

There was a pathos too, it occurred to me, in that the ordinary soldiers, whom for so many the view displayed in the panoramas was their last sight on earth, would have had no access to the information revealed by the military panoramas of the time.

What we ourselves can see now in the panoramas, they were ignorant of. There is also something affecting in the names that we can see the ordinary British soldiers gave their own and the enemy positions: Gin Alley, Sausage and Mash Valley, Whiskey and Soda Trench etc – in front of Hawthorn Ridge, we see that one battalion (that would lose 90% of its number that morning) advanced from a trench they had christened Happy Valley. Looked at from the other perspective, it could be said that the panoramas tell an optimistic and redemptive story.

The horrors of war have been replaced by the healing powers of nature. The soldiers who inhabited the world of the annotations (many of whom thought quite literally that the war would never end) might be consoled to see that the world has moved on and that their sacrifice is still honoured, that wooden benches for tourists now stand on the site of the great mine craters and that the only killing is dispensed by insectide from the back of a farmer’s tractor.

The creation of the panoramas has taken two years of development and research and over a dozen trips to the battlefield.

Using both the original military maps of the time and the first-hand testimony of soldiers who were there – together with the incredibly generous help of experts in the German defences – I have tried to make the substance of the annotations (the positions, distances and military map references) as accurate as possible.

The greatest challenge was choosing the points from which the photographs were taken – points that were at once strictly faithful to history, that would allow the best composition for the photographs and that would tell a comprehensive story of the battle.

The photographs were taken over a 3-week period over the 1 July 2015, each panorama being taken at the exact moment the first waves of British soldiers attacked. I needed good weather. I wanted to replicate the conditions of the morning of 1 July 1916 which – again ironically – were uncommonly beautiful.

I was lucky. In exactly the same way as the battlefield panoramas of the time, the panoramas were taken in panned sequence (each panorama is a composite of at least 11 separate stitched images) – albeit without the distraction of bullets and shellfire.

The Zero Hour Panoramas exhibition will be at the Sladmore Contemporary (Bruton Place) from 1st to the 15th July. More information here.