In Eric Bricker’s 2008 film, Visual Acoustics – The Modernism of Julius Shulman, the veteran photographer declares; ‘Architecture affects everybody […] every part of person’s life is based upon an architect’s presence.’

Little wonder, perhaps, that Shulman – who died in 2009 at the age of 98 – spent his working life documenting the formal specifics of Southern California’s modernist buildings – buildings which themselves helped to define his own particular photographic practice.

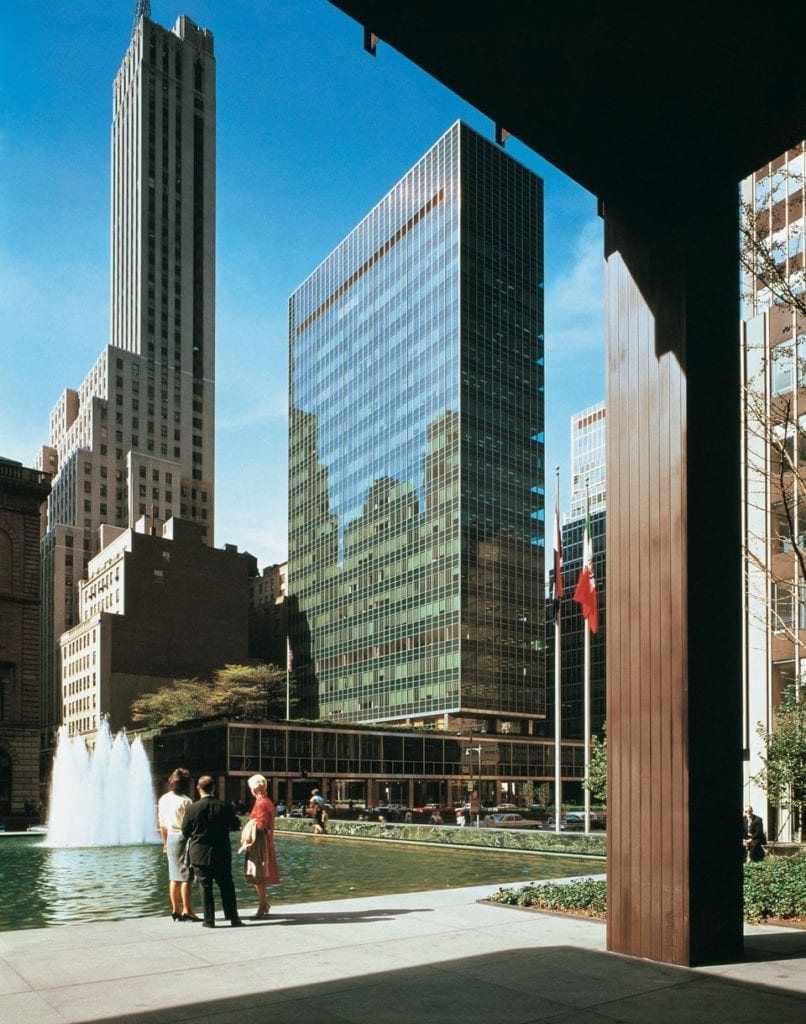

His lens is concerned with the connectivity of humanity and nature via constructions of spectacular geometric discipline. It’s a fixation with an artistic identity influenced heavily by the minimalist practices imported from Europe in the first half of the 20th Century, and one which, to this day, draws attention to the processes and materials used in creating the buildings, from girder to gutter.

But Shulman’s is a highly particular oeuvre, even within modernism. Born in NYC, but raised on a farm in Connecticut, his eventual move to Los Angeles developed in him a point of view that posited buildings as highly influenced – defined, even – by their natural surroundings.

His first paying gigs were working for the Austrian-born architects, Richard Neutra and Rudolf Schindler, who are widely considered to have co-founded Southern Californian modernism. They clearly saw a malleable talent in the 26 year-old, fresh from two aborted University degrees.

Recalled Shulman: ‘At the end of seven years, I woke up early – three o’clock – and I said “Wait a minute, what am I doing here? I’ve been going to University for seven years and I think I’ve had enough.”’

Shulman’s relationship with Neutra fast tracked him in the world of architectural photography. He was introduced to the likes of Gregory Ain, Harwell Harris, Raphael Soriano and J.R. Davidson, and whilst this informal collective began to define their own brand of modernism, Shulman’s role developed from jobbing snapper to architectural tastemaker and talent scout.

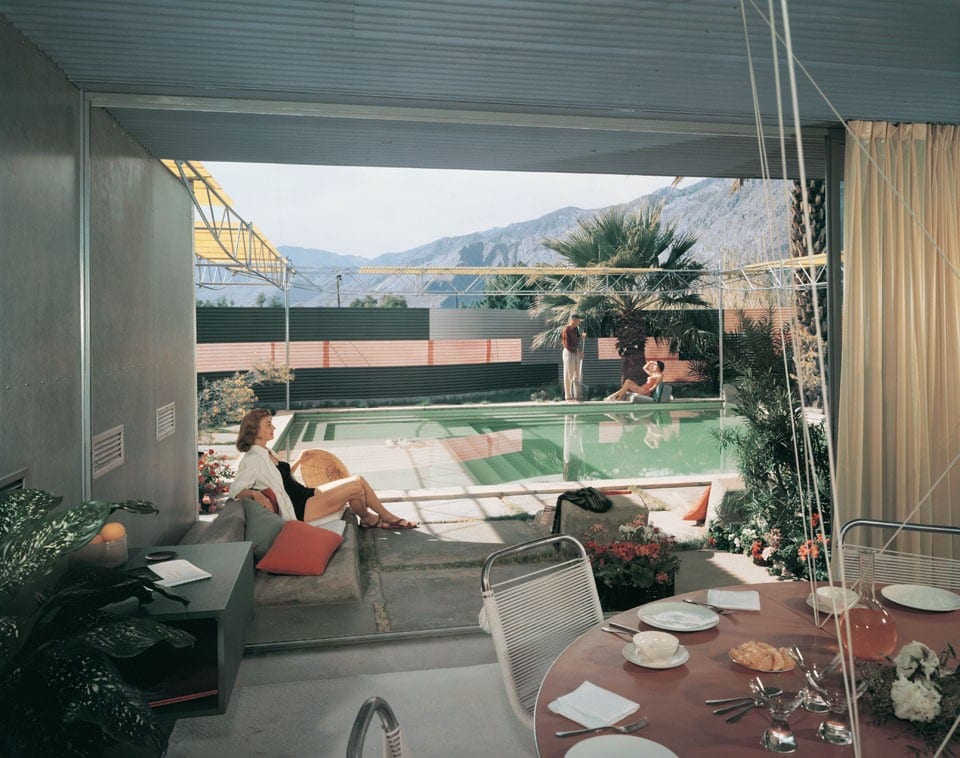

To the broader American public, Shulman’s images represented West Coast style and innovation, with straight lines, bold colours and dynamic backdrops. His preference was to permeate this geometry with human activity; well dressed, good looking families completing elegant tasks.

His images of the Frey residence in Palm Springs, CA represent this increased role. Albert Frey is widely considered to be the first disciple of modernist master, Le Corbusier, to build in America.

Frey fell in love with Palm Springs and ended up constructing the city hall, the airport and two houses for himself, amongst others. It is a desert resort town defined by a modernist character: Conscious of its quixotic location, but all the time, defiantly confident and forward-looking.

Recalled Shulman in 2008: ‘It’s a house designed to meet and live with the desert! Why can’t new architects, young architects, be instilled with the spirit of a desert? To introduce them to a building in a desert […] on a so-called impossible piece of property, you’re constructing a house that melds with and in the landscape!’

Though the clarity of Shulman’s vision helped to elevate architectural photography into its own art form, he became disillusioned as modernism declined and morphed into postmodernism in the late 60s and early 70s.

But maybe that is what backs up Shulman’s status as an essential progenitor of architectural photography – a stylistic defiance. His real skill was in understanding buildings in the way that they had existed in the architect’s head – before the drawing board. As Richard Neutra put it, the photos ‘revealed the essence of my design’ – it’s a creative legacy of reverie.

Julius Shulman – Modernism Rediscovered is published by Taschen in Hardcover, 3 vols. in slipcase, 24.9 x 31.6 cm, 1008 pages. £ 99.99 / $150. For more info, visit www.taschen.com