It’s Saturday night, and darkness has spilled across the city, transforming Manhattan’s sidewalks into a catwalk of bacchanalia, spotlighted by street lamps and neon piping. Clusters of sinewy figures in tank tops lean on metal railings outside favourite haunts such as Studio 54 or Paradise Garage, hips cocked, smoking cigarettes.

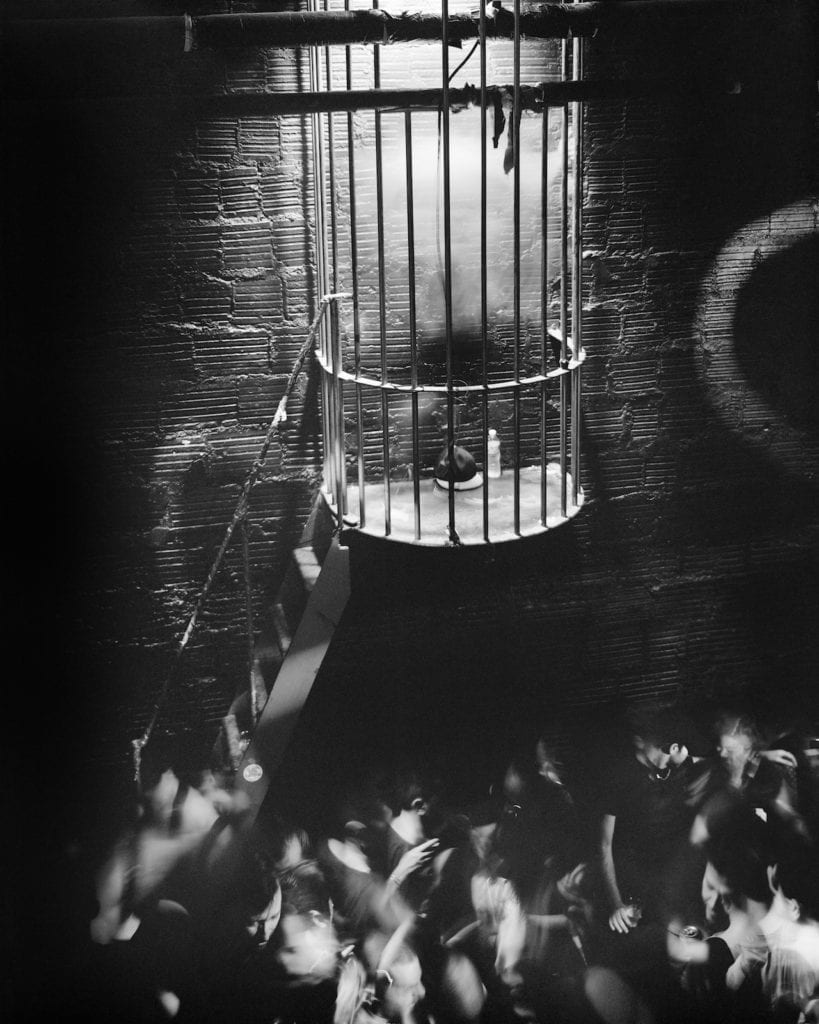

A wall painting of a large, fleshy tentacle reaching out of a rolling wave frames a set of black doors with signs indicating ‘General Admission’ and ‘VIP Only’. Stepping into a hidden world, you head downstairs and join a steadily expanding crowd of bodies swaying to tribal house beats, swirling in artificial mist and the odour of hormone-spiked sweat laced with chemical stimulants. Faces blur. Everything begins to lose focus.

It’s just past midnight when we join photographer Richard Renaldi’s journey through the night. The timestamp [00.07] captions the first image – a shiny, half-full dance floor – in his new photobook, Manhattan Sunday, published by Aperture. Shot over five years, the book delineates a night out on New York’s gay clubbing scene, celebrating its throbbing sexual energy and tapping into the discernible vulnerability of its participants.

“This is the first time I have published a book or a project where I didn’t name the people,” says the photographer. “I always felt like names are really important, but this is much more dreamy, so I felt I could let go of that requirement. Those ‘Manhattan Sundayers’ – the revellers – pass from one generation to the next and experience the night living through and acting out fantasies and pleasures.”

Renaldi has been living in New York since 1986 and is about to pop out for a bagel when he receives my call, but happily postpones his morning snack. He came to the Big Apple from Chicago, where he was born 20 years earlier. Growing up, he was no stranger to the windy city’s underground clubbing scene, finding his identity dancing to new wave and alternative music in the booths of DJs who soon became his close friends.

He graduated from New York University with a BFA in photography in 1990, by which point he had become immersed in that city’s legendary party scene, by then alongside a new, unwelcome guest. AIDS wounded New York more than any other city in the US, thriving among the gay community and tormenting what had come to be a culture of spontaneity and nonchalance. It was perhaps this deep connection and personal experience of the hidden world that prompted him to revisit his old playground.

Using a classic large format 8×10-inch camera fixed securely on a tripod, Renaldi, now in his late 40s, befriended club owners and promoters, who let him plot in the tightly packed space where standing stationary and unable to move with the partygoers, hidden under a cape and relying on the support of a sprouting tripod, was “a little nutso, given the liability issues… but fun”.

These interior shots of dalliance and disco make up only the first quarter of the photobook. All too soon it is 4am. The volume of the music dims and the colourful lights on turntables flicker off, leaving plastic shards of cast-off cups on the floor and a muffled hum of bass mulling over in your brain as the only trace of the past few hours of indulgence. The masquerade of the nightclub fades away, guards are dropped and shouts turn to whispers.

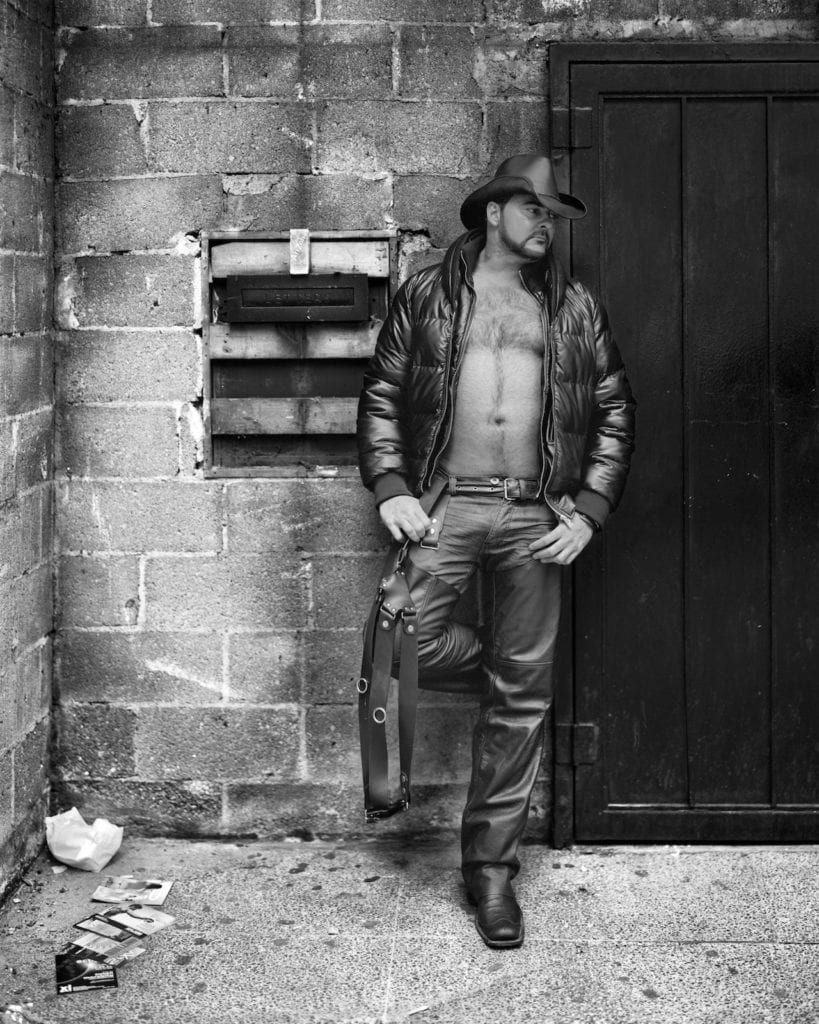

“I was trying to recapture that experience that I would have coming out of a club and, maybe still a little high, walking home, seeing the city in this tranquil, golden, beautiful, quiet light. But none of the people in the pictures project that ‘walk of shame’.”

With each portrait, Renaldi captures a different state of mind. He shoots in black- and-white, “not only to hint at that feeling of nostalgia and timelessness” but to soften the image, muting the noise of colour and drawing your focus into the characters’ stories. Just as he balances the tonality of light, he creates a mellowness of mood felt by the subject, himself and the viewer.

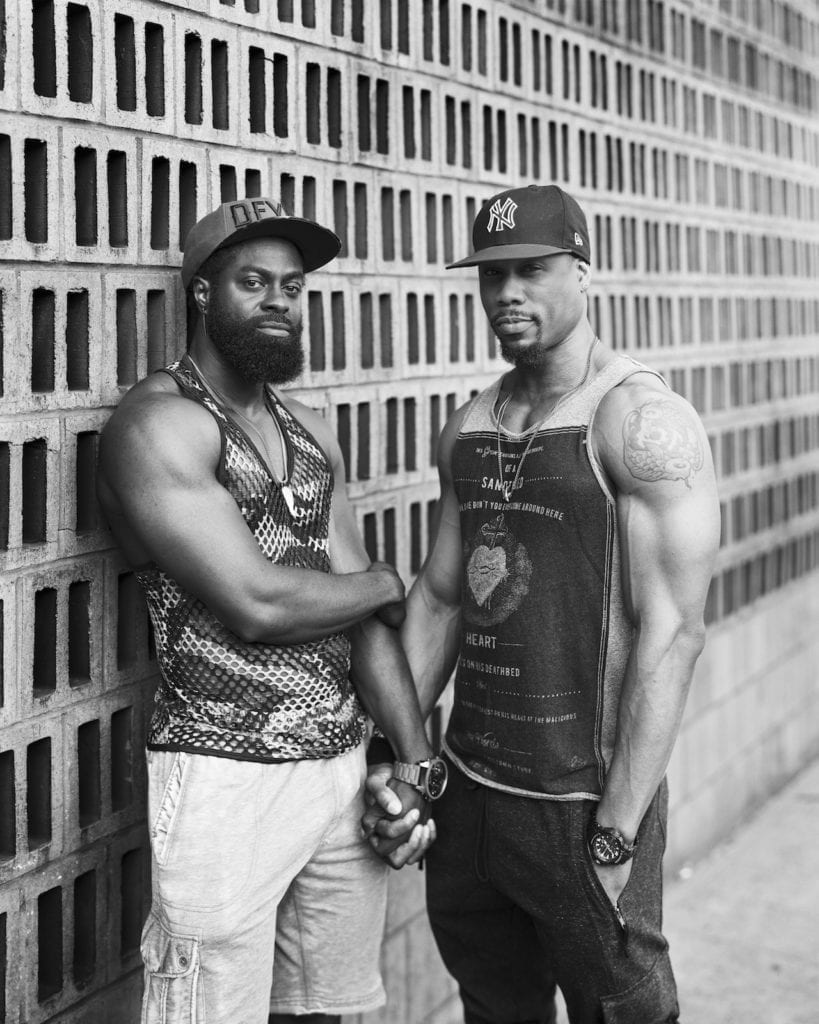

Nevertheless, approaching people to take their portrait in the early hours of the morning demands an element of trust and the development of a relationship, albeit a transient one, with a stranger. It is an investigation of ambiguity and vulnerability that Renaldi has explored previously, with his enchanting project Touching Strangers.

The portrait series, which he worked on between 2007 and 2014 and which has continued to receive worldwide acclaim in the years since, shows two or more strangers from all over the US who had never met before, physically interacting with each other as if they were family and friends.

“Touching Strangers was a dare, and with Manhattan Sunday too there is an element of the subject letting down a guard, but it wasn’t as directed. With everyone who goes out [clubbing] there is a yearning for that sort of thing – glamour and a little bit of desire.

“Of course, it was painful, just like Touching Strangers – it was really painful to go and put myself in this vulnerable position, to ask two or more people to do this strange, unusual performance with each other.”

The pain he refers to here is revealed as Renaldi groans, recalling setting his alarm for 3 or 4am, dragging himself out of bed when it was still dark, and venturing out into the city, almost always alone. “But once I got outside and was shooting it became this wonderful, sometimes magical, private, inspiring experience.”

As well as appearing in a book, the series is being shown in an exhibition at the George Eastman Museum in Rochester, New York, until 11 June. Lisa Hostetler, the curator-in-charge of the department of photography and the curator of the show, was enchanted not only by the charisma of the pictures, drawing a comparison with American fashion and street photographers active in the 1940s and 50s, but also by their collective message of unity and community.

“In that limbo of late at night and early in the morning, especially in Manhattan, you get a real mix of people,” she says. “Some are going to work and sweeping the streets, others are stumbling home from a night out on the town.

“There is this interesting interweaving of people at different points in their daily lives – this clash of cultures that might not normally be in the same place at the same time. It feels like it’s only you and a few other people on the street, because it’s less populated at that time. There is this sense that you’re all experiencing something secret because everyone else is sleeping.”

Hostetler praises Renaldi for his portraiture, but what is surprising, and different from his previous projects, is the prominence of landscapes and architecture within the narrative. “In making a love letter to Manhattan, I don’t think it’s just the people, it’s also the city,” he says.

He captures a ‘portrait’ of the empty cityscape and quiet streets, contrasting it with the loud and vocal nightclubbers. “I think there’s conversation between people and space, and people and place. When something has that sort of essence or quality you can also make a portrait of non-living matter.”

He recalls his first monograph, Figure and Ground, published in 2006 and composed of portraits of local residents in north New Jersey. Renaldi decided to turn the camera to landscape format and, unconventionally, shot his subjects horizontally.

“When I did that, I discovered there was this whole other element and subject in the pictures, which was the background and the city. That’s when I really started to pay attention to background and subject and their relationship to each other.”

Hence, the photographer speaks of the “romanticisation” of New York for this project, and his love of its tall apartment blocks and grandeur. His partner of 17 years, Seth Boyd, started out as an architectural photographer.

“I learned a lot from him about how to photograph architecture cleanly and respectfully to the lines. It was very natural. And the way people are also standing as grand as the buildings – there’s a nice comparison to be drawn between the two.”

One such cityscape is presented as a fold-out gateway in the book, flattering its full panoramic splendour. With each turn of the page that follows, twilight turns to sunlight and shadow, and the sky’s soft glow massages the city awake.

The portraits taken in this part of the day are particularly unique – some individuals tilt their heads back to welcome the sun’s glow, some hide under hoods and glasses. The sound of clattering heels on the concrete is replaced by gushing water from hosepipes ridding the pavements of last night’s frivolity. A blonde wig lies discarded on the ground and a couple of small brown-glass bottles in the gutter.

The photographs are quiet, a sense of peacefulness hangs in the air. “I often thought of those transcendent mornings spent inside nightclubs as echoes of the Sunday mornings when I attended mass as a child,” Renaldi writes.

The last photograph is taken at 10.35am. A young man rests his arms and chin on the table, next to a glass of iced water. He wears a paper wristband with bold, black lettering – perhaps the name of the club he has just left. His expression is calm and he appears lost in thought as he gazes at a bowl of mini plastic milk cups.

“Sunday is the quietest of days,” says Renaldi. “Manhattan Sunday is not just one singular night, it’s all those Sundays. I wanted it to be a dream that you can come into, leave and come back. I wanted there to be more mystery, because I think there is some mystery in the night.”

Renaldi ends his personal documentary with an essay explaining the context of the project, and revealing a deeper connection to it. He reminisces about the first club he attended, aged 11, talks of the loss of an ex-boyfriend to recreational drugs, of the discovery shortly after that he was himself HIV positive, and also of being lucky to seroconvert just as new life-saving drugs became available.

Last year, he became a fellow of the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, which he says “felt like it gave me some authority to really pursue this project with abandonment, and put all of myself into it. I think it did what it was supposed to do. It’s my sexiest project, for sure.”

Manhattan Sunday is published by Aperture, and on show at George Eastman Museum until 11 June. This interview was originally published in BJP #7856 ‘Tales of the City issue’. renaldi.com, @renaldiphotos on Instagram