Most photographs are one-night stands, quickly consumed then forgotten. Very few offer the possibility of a long-term relationship, but for quite a few years I have found myself returning to one very unlikely picture. I say ‘unlikely’ partly because it’s so unusual, but really because I don’t even know if I like it. I know it fascinates me, and fascination doesn’t have much to do with likes or dislikes. To be fascinated is to be captivated, compelled, absorbed, beguiled even.

The photograph in question was made in 1920. The author, Man Ray, had been asked by a collector to photograph a number of her artworks. “The thought of photographing the work of others was repugnant to me, beneath my dignity as an artist,” he recalled in his enjoyable memoir.

Pondering the commission, he visited his friend Marcel Duchamp in his New York studio. The place was filthy and in the middle was a horizontal sheet of glass covered in dust. Duchamp had been letting the dust accumulate as one of countless stages in the making of his great opus, The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even (also known as the Large Glass) 1915-1923.

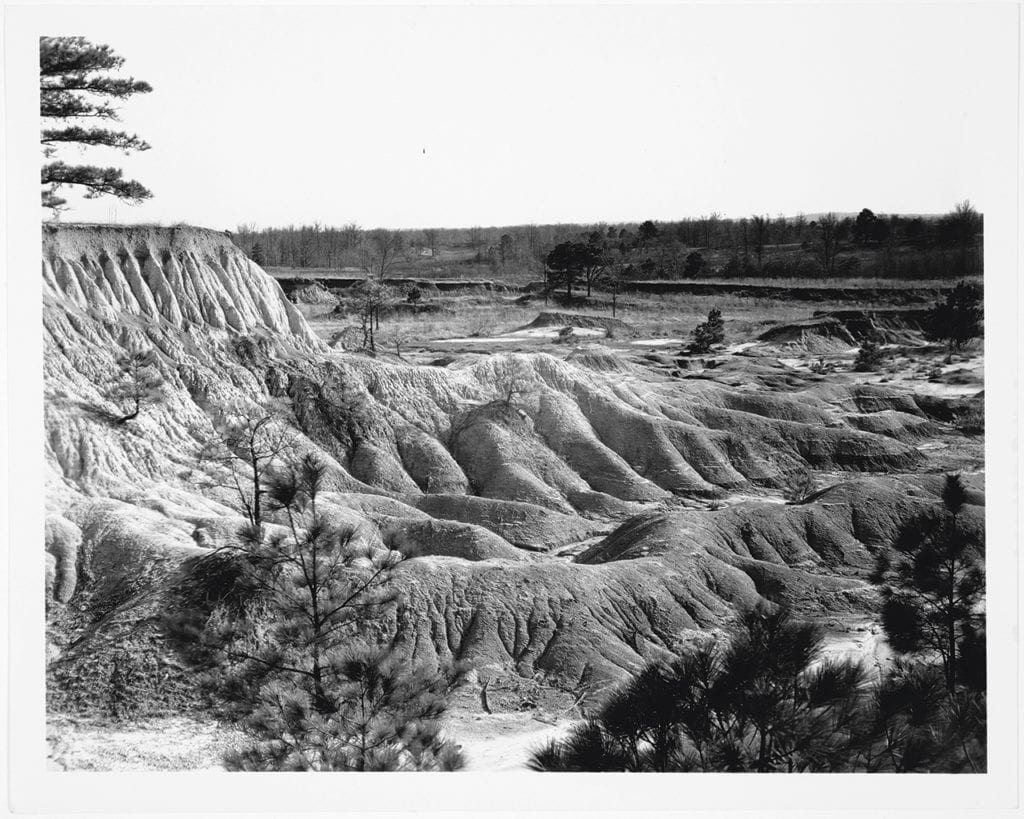

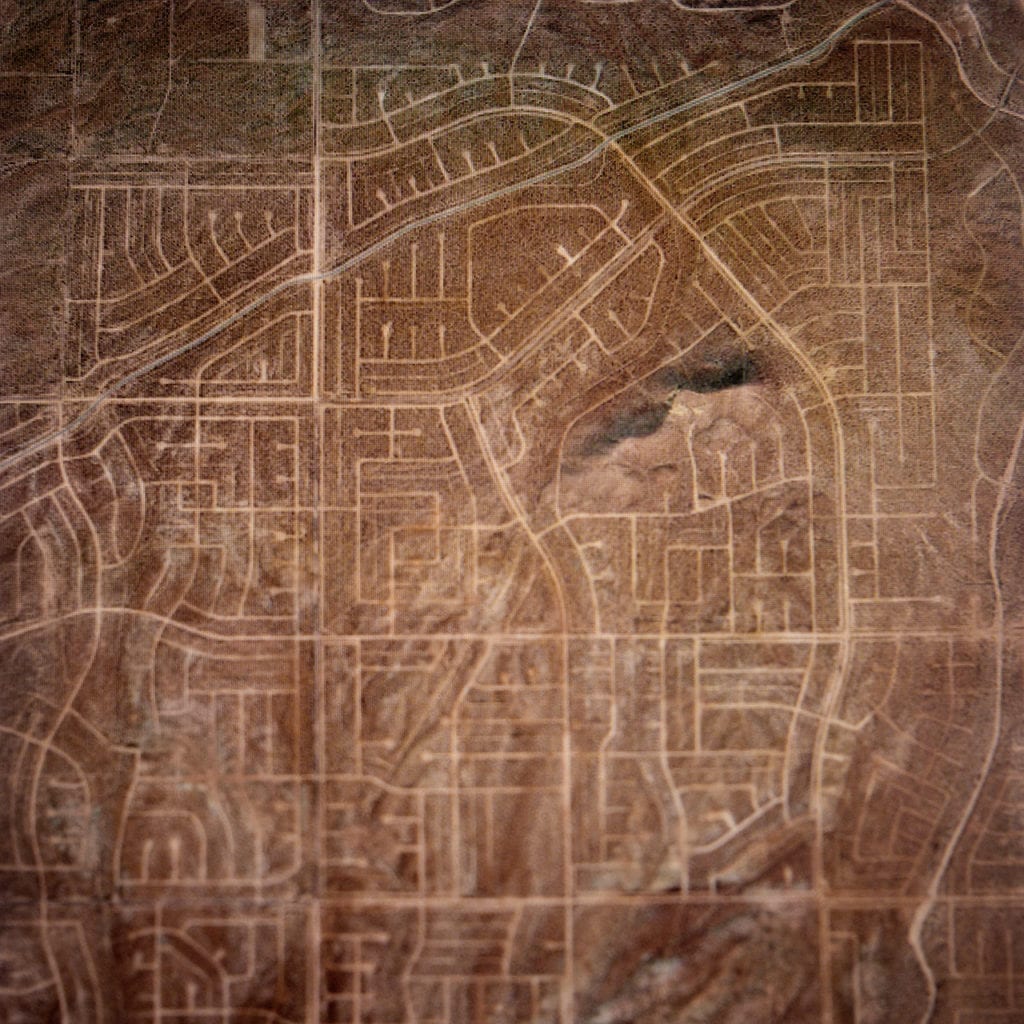

Duchamp suggested Man Ray practise his documentation. The resulting image was strange: an oblique gaze down at an obscure surface with no obvious subject matter or scale. When it was first published, in October 1922, it was captioned View from an aeroplane. That same month, in London, TS Eliot published the great poem of the modern era, The Waste Land, which contains the line: “I will show you fear in a handful of dust.” Also that month, Ernest Hemingway flew over France, later writing that having seen Paris from above, he now understood Cubism.

In the 1920s, ’30s and ’40s, the photograph led a curious life in and out of various avant-garde journals, each time cropped, titled and contextualised a little differently. This was the period in which vanguard artists were exploring new angles, new relations of image to language, and the uncertain terrain between the photograph as document and artwork.

In 1964 it came to be formally titled Dust Breeding [Élevage de poussière], and an edition of ten prints was signed on the front by both Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp. In books and shows about Man Ray’s work the photograph tends to be presented as a visionary image by a pioneer of photographic art. In the context of Duchamp however, it is regarded more as a document – a production shot simply showing his Large Glass in the making.

As Duchamp’s reputation grew in the 1960s, the image appealed to mixed media artists looking to make work at the interface of photography, sculpture, process and performance. Dust Breeding is even reproduced as a keynote work in the 1970 catalogue of the first major survey of conceptual art (Information, Museum of Modern Art, New York), and by 1989, when photography reached its 150th year, it was included in many of the big celebratory shows.

It was there on the wall when the Royal Academy of Art in London finally accepted photography as an ‘independent art’, as they called it; that’s where I first saw it, and I could not think of a less independent image. It seemed tied to so much, so dependent on other bits and pieces of knowledge.

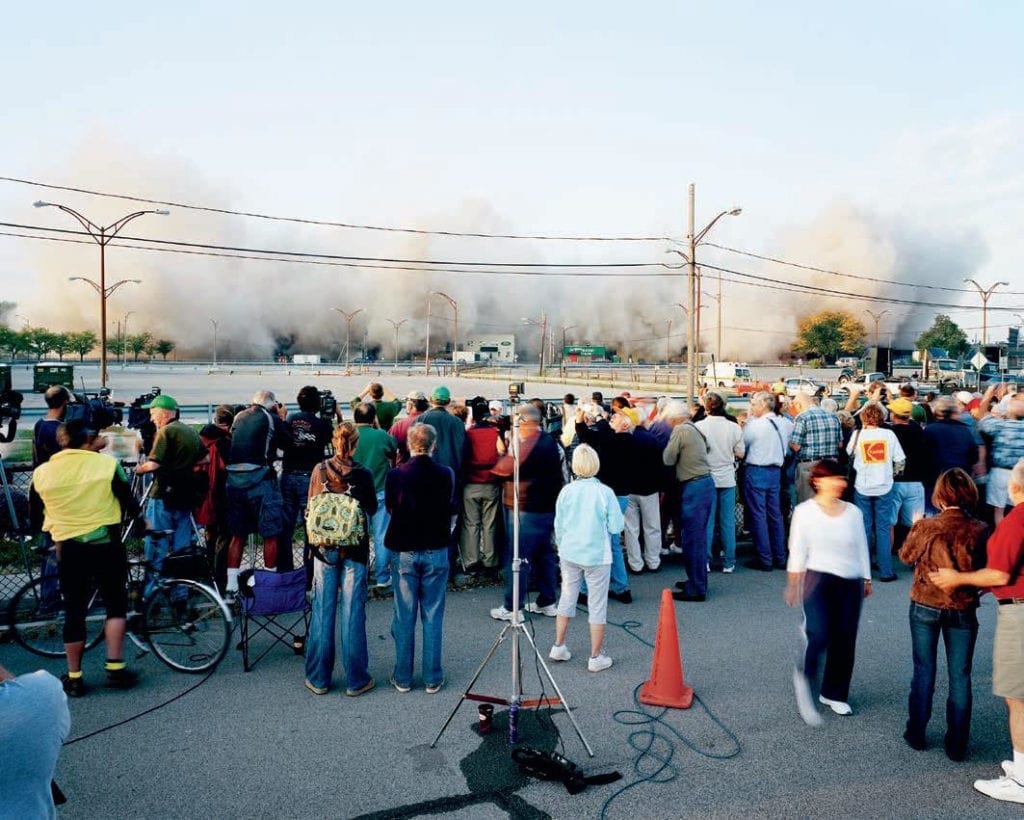

In more recent years, Dust Breeding has continued to haunt photography. It often crops up in debates about the medium’s status as index or trace, in shows about abstraction or artists’ interest in simple materials (you can’t get simpler or plainer than dust), and even in discussions of landscape imagery.

Recently, Le Bal in Paris asked me what my ideal exhibition would be. One ought to be wary of speaking about such things, just as one should be wary of blurting out one’s dreams – and I must admit, I have been thinking about this photograph for so long that there are indeed moments when it seems slightly dreamlike to me.

Nevertheless, Le Bal is nothing if not an experimental institution, so the team gave me a chance to put together a show and an accompanying book taking this image as its starting point. It amounts to a speculation about photography, about artworks, about documents, about our relation to dust and about the last century more broadly. What if that strange photograph, taken in 1920, really does signal the dawn of the modern age, with all its complications? Can a history be assembled from the perspective of dust?

A Handful of Dust is on show at Whitechapel Gallery until 03 September; a related symposium, Notes on the Index, will take place on 17 June, and a curator’s tour lead by David Campany on 20 July. www.whitechapelgallery.org The accompanying book is published by MACK Books and costs £30. www.mackbooks.co.uk The exhibition first went on show at Le Bal, Paris, from 16 October – 31 January 2016. www.le-bal.fr. This article is taken from the November 2015 issue of BJP, which is available via www.thebjpshop.com