The Mediterranean sun is suffocating; blistering hot and burning the skin. Standing in front of me, beads of sweat on his face and partially obscured by patches of black shadow, Daisuke Yokota is patient and motionless as I photograph him. Thirty-six frames later, the shoot is finished. “That was intense!” he exclaims softly, with a smile of complicity.

We are in Arles, where in July 2016 he showed Mortuary, one of his signature sculptural installations, made up of heavily manipulated, elongated photographic forms. He had been selected for the Rencontres photofestival’s Discovery Award, though in truth this cat had been long out of the bag – Yokota exhibited in Arles in 2015, showing his almost imperceptible inky-black prints from his Inversion series as part of Another Language: 8 Japanese Photographers, curated by Simon Baker of Tate Modern.

And in the preceding half decade, his intriguing, visually arresting performances, experiments, installations, books, soundscapes and collaborations have blazed a trail from Tokyo to wider international acclaim, taking photography on a journey to the extreme.

In this he is a revolutionary, with neither pretension nor timid creativity. The sheer energy with which he produces work is extraordinary, verging on obsessional and driven by a desire to constantly record, destroy and then recreate. Anxiety is the fuel. “In my mind, I have an image of burning energy in continual production,” he says.

“Often, my personality catches me in anxiety and frustration. If I stop, I will be stuck in a vicious circle of these feelings so I try to burn those negative thoughts and transform them into the energy for production.”

We are in Arles, where in July 2016 he showed Mortuary, one of his signature sculptural installations, made up of heavily manipulated, elongated photographic forms. He had been selected for the Rencontres photofestival’s Discovery Award, though in truth this cat had been long out of the bag – Yokota exhibited in Arles in 2015, showing his almost imperceptible inky-black prints from his Inversion series as part of Another Language: 8 Japanese Photographers, curated by Simon Baker of Tate Modern.

And in the preceding half decade, his intriguing, visually arresting performances, experiments, installations, books, soundscapes and collaborations have blazed a trail from Tokyo to wider international acclaim, taking photography on a journey to the extreme.

In this he is a revolutionary, with neither pretension nor timid creativity. The sheer energy with which he produces work is extraordinary, verging on obsessional and driven by a desire to constantly record, destroy and then recreate. Anxiety is the fuel. “In my mind, I have an image of burning energy in continual production,” he says.

“Often, my personality catches me in anxiety and frustration. If I stop, I will be stuck in a vicious circle of these feelings so I try to burn those negative thoughts and transform them into the energy for production.”

Six months later, on a freezing-cold day in Paris, I have an appointment at the studio of Yokota’s French gallerist. Jean-Kenta Gauthier represents some of the most interesting and inquisitive photographers around, from Anders Petersen and Daido Moriyama to JH Engström and Raphaël Dallaporta.

Here in his studio, laid bare on the table, is Yokota’s book Matter (a 3D version of which went on show at Foam in Amsterdam this summer). It is extremely fragile, with radiant abstracted colours peppered with obscure figurative referents of solitary people. The pages are reminiscent of partially skeletal leaves, layered and cracked, coated with a heated wax.

Though organic and accidental, they remind me of the perfect rendering of Gustav Klimt’s gold leaf patterns – such is the vibrancy of their textured colours. This book is one of only 25 in existence, and considered an artwork by Yokota. Each is unique, handmade on paper that is almost transparent. They wax lyrical on destruction and rebirth, and on the endless regurgitation of matter as it morphs into other forms.

“For Yokota, the process is very important, but this process is unified by layers on layers,” says Gauthier. “This is how he physically makes work. First, he avoids selection – which is a fantasy for most photographers – and, without selecting the images, he coats the surface with wax. Applying heat to the wax, the pigment allows a transformation to happen. He gathered those pages, bound them and made a handmade book.”

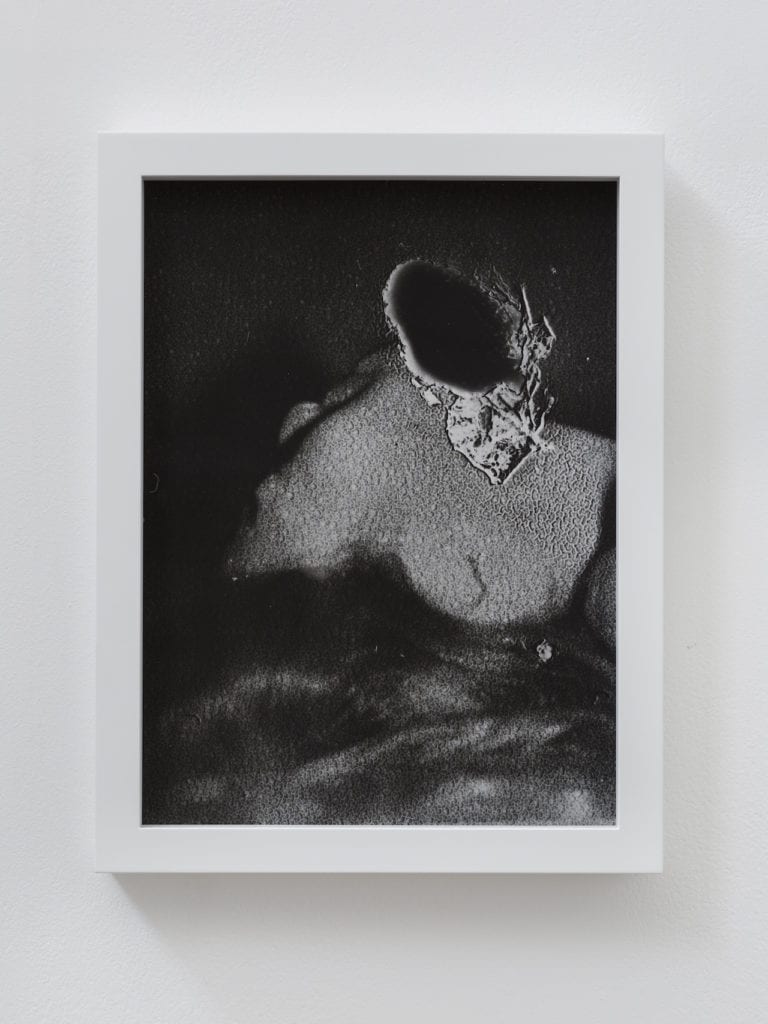

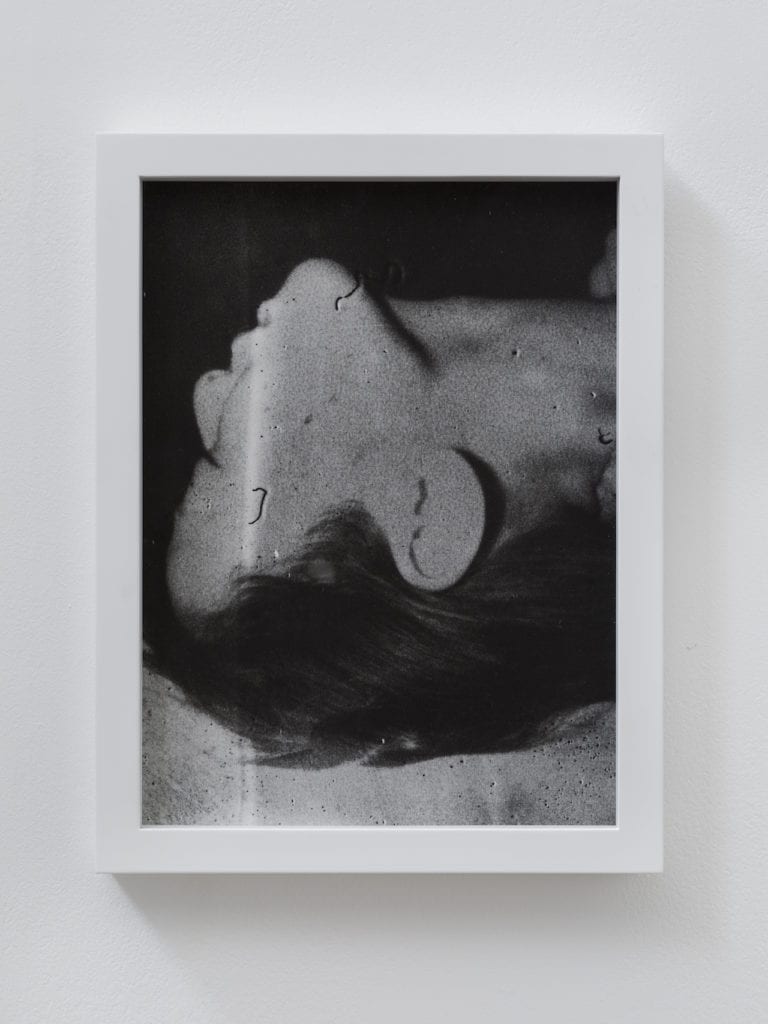

His Inversion series realises similar thought processes, yet in markedly different form; obscured, inky-monochrome prints that are reminiscent of the black negative peeled and discarded to reveal a Polaroid. They are, in fact, solarisations taken from the pages of Matter, so that again new work is created from the source material, which in itself is taken from other source materials.

Gauthier is wary of what he calls a “new orientalism” regarding representations of Japanese photographers in the press or in exhibitions, which have a tendency to patronise through perpetual stereotyping – a trace, perhaps, of imperialist romanticising of the ‘other’. He also worries about a tendency towards the lazy categorisation of photographers that stifles comprehension and appreciation.

But although I am sure he has been asked a thousand times before, I wonder if Yokota feels that there is some lineage carried from the Provoke photographers, especially to Daido Moriyama’s seminal 1972 book, Farewell Photography.

“I had that idea once, but I do not now,” he says. “The situation is different now; there is no shared recognition or mainstream [notion] of ‘photography’ any more. Some images may look like Provoke but this is quite natural. Really, there is no philosophical meaning in making work in the same context. I believe it is time to reconsider photography detached from that understanding.”

Last December, the Berlin-based photobook publisher, Michael Kominek, invited Yokota, alongside other photographic artists Yoshi Kametani and Hiroshi Takizawa, to produce work that would culminate in books by each of them and also one collaborative book, as part of his newly founded, month-long residency programme. Kominek’s role was to provide a framework and edit the output.

“Earlier in the year I had organised a residency [the programme’s first] with British photographer Antony Cairns, who brought with him an archive of photographs that he reworked,” says Kominek. “But with Kametani, Takizawa and Yokota, they arrived with nothing, so as to produce fresh work from scratch of their experience in Berlin. They worked mainly at night. Yokota particularly enjoys photographing at night.”

Kominek led them on nocturnal adventures, driving them around Berlin to night clubs, strip clubs, the fairground, a boxing match between German and Polish teams in Spandau (Germany won), and to the Liepnitzsee lake, where Yokota fell into the below-freezing water. “My life in Berlin became like a routine,” says the photographer.

“I woke up after dusk and went to bed in the morning. So I did the shooting at night, wandering the city. One month looked long at first, but it turned out to be very short in the end. It is tough to work in such a limited amount of time but I hope it will be more vivid work.”

Kominek has edited the results and produced the book, simply called Berlin. The process of this work is complex and idiosyncratic, employing unorthodox cameras, boiling the negatives during processing and reshooting the prints.

Much of the process remains undivulged, for the secrets of an alchemist must be protected. To relinquish control is to be free from constraints, yet to harness the mistakes, appreciate the accidents and embrace the failures takes great concentration, confidence and, paradoxically, a large degree of control.

Yokota’s innate compulsion to make work was apparent in his first week in the German capital, when he fell ill and was unable to leave the apartment. His response was to set up an infrared camera in his bedroom and film his ghostly figure sleeping or glued to a laptop. Essentially, it is a recording of nothing – of empty time and space – but it somehow attains an eerie substance that recalls a film piece he made in a hotel room called Room 1.

“The meaning of Yokota’s work is in the process,” says Kominek. “For me, the experience of witnessing and participating in the making of images was extremely enjoyable but, of course, it is always about the result, how it looks. Yokota is influenced by Gerhard Richter and Michael Schmidt, but to a certain degree he is free of politics – even though I would say that Berlin is similar in a sense to Schmidt’s Waffenruhe in terms of apparent arbitrary subject matter. However, it is important also not to be restricted by being too intellectual, but to focus on just making.”

“I woke up after dusk and went to bed in the morning. So I did the shooting at night, wandering the city. One month looked long at first, but it turned out to be very short in the end. It is tough to work in such a limited amount of time but I hope it will be more vivid work.”

Kominek has edited the results and produced the book, simply called Berlin. The process of this work is complex and idiosyncratic, employing unorthodox cameras, boiling the negatives during processing and reshooting the prints.

Much of the process remains undivulged, for the secrets of an alchemist must be protected. To relinquish control is to be free from constraints, yet to harness the mistakes, appreciate the accidents and embrace the failures takes great concentration, confidence and, paradoxically, a large degree of control.

Yokota’s innate compulsion to make work was apparent in his first week in the German capital, when he fell ill and was unable to leave the apartment. His response was to set up an infrared camera in his bedroom and film his ghostly figure sleeping or glued to a laptop. Essentially, it is a recording of nothing – of empty time and space – but it somehow attains an eerie substance that recalls a film piece he made in a hotel room called Room 1.

“The meaning of Yokota’s work is in the process,” says Kominek. “For me, the experience of witnessing and participating in the making of images was extremely enjoyable but, of course, it is always about the result, how it looks. Yokota is influenced by Gerhard Richter and Michael Schmidt, but to a certain degree he is free of politics – even though I would say that Berlin is similar in a sense to Schmidt’s Waffenruhe in terms of apparent arbitrary subject matter. However, it is important also not to be restricted by being too intellectual, but to focus on just making.”

Mortuary, using 20m rolls of photographic paper, has something of the anthropomorphic about it, of dead materiality. And when it was shown in Arles, Yokota brought in another interest – sound – to the installation, so that it amplified a very deep tone, causing vibrations that shook the inner body.

“I used four rolls of Baryta paper of 108.5×2000cm,” says Yokota. “My studio is very small, 4×5m, so I wanted to use this size paper but I could not do this for a long time. But I changed my idea to make the work reflecting the problem itself. My studio is not big enough to use the enlarger, so I used the sunlight to expose for the rolled paper.

“Because the studio is small, it causes damage on the paper. Also, there are no containers that the paper can fit so there will be errors and mistakes in the development. I took advantage of these situations by not developing it in the correct way, not washing it much, or using sulphur to enhance the stains – to make a piece which can be physically felt and experienced.”

Gauthier recalls that the experience of constructing this work was painful for Yokota. “He remembered something as a child when he suffered an illness and fell into a deep fever,” he says. “When a child has a fever, they have hallucinations, more than an adult will experience, and he remembered these weird visions he saw of a sphere of light and fire pushing through a black, obscure space. This memory returned to him only recently.

“After some research, he discovered that this vision was common among many artists, and that they have produced work based on this vision. Herman Melville wrote Moby Dick using the whale as some kind of metaphor inspired by this vision.”

And so, despite the importance of the process, the question about Yokota’s work so far is: ‘What is its meaning?’ “The process is about memories that become faded over time in the mind,” says Gauthier. “Essentially, the memories change as they get mixed up with other memories.”

The photograph is a record of a memory and, by extension, Yokota’s works are manifestations of latent recollections that emerge from the unconscious. They often address figuration and fragmentation through layering, but Mortuary began purely with abstraction. He conceived that photography is always about the surface but never about the body.

“He wanted to consider that the paper is the flesh and what is on the paper is the skin, and through this metaphor, we enter into a deeper questioning of his own and our collective memory, and to also question photography itself,” says Gauthier.

“Both the process and the meaning are important,” says Yokota. “But it is difficult to include the process in the image itself. In other words, if the picture was taken in a severe situation, it can record the severity. But photography never includes it. To include this process into the final output, I tried to maintain the textures, sounds and smells to give the physical feeling of the process.”

After an exhibition in Xiamen in 2015, the installation was burnt in a vacant space, like a funeral pyre, though whether this can be interpreted as a ritual, an execution or both is wonderfully ambiguous. The ‘burn-out’ process was documented in 4000 photographs and then these, having been processed and manipulated, were revived to form a new, large-scale work, of which some have made up the book.

With all his energy speeding headlong, is he in danger of running out of fuel? His answer is modest. “I have a fear of that all the time. But if you look around there are so many extraordinary artists and, when I compare, I have done nothing. If I burn out now, I was not good enough.”

Emergence by Daisuke Yokota is on show at Roman Road gallery until 11 November www.romanroad.com jeankentagauthier.com gptokyo.jp This article was first published in the April edition of BJP, available from the BJP shop www.thebjpshop.com