The opening image in his latest book, Sacrifice Your Body, typifies Roe Ethridgeʼs approach. At first sight, itʼs just an ordinary product shot of a Chanel No 5 bottle and its packaging, but closer inspection reveals chipped paint, stray drops of perfume and an intruding wasp. Rippling the surface of a glossy ad with droll other-world elements, itʼs the kind of image thatʼs made him a star in contemporary art, fashion and advertising.

Like Juergen Teller, he shoots both commercial and editorial (for the likes of Kenzo, Self Service, Acne Paper and W) alongside his own artwork, and has been shortlisted for the Deutsche Börse Photography Prize (in 2011, alongside Elad Lassry, who heʼs often cited with as evidence of a new trend for dry conceptualism). The Deutsche Börse organisers described his work as follows: “Blurring the boundaries of the commercial with the editorial, and the mundane with the highbrow, Ethridge’s conceptual approach to photography is a playful attack on the traditions and conventions of the medium itself.”

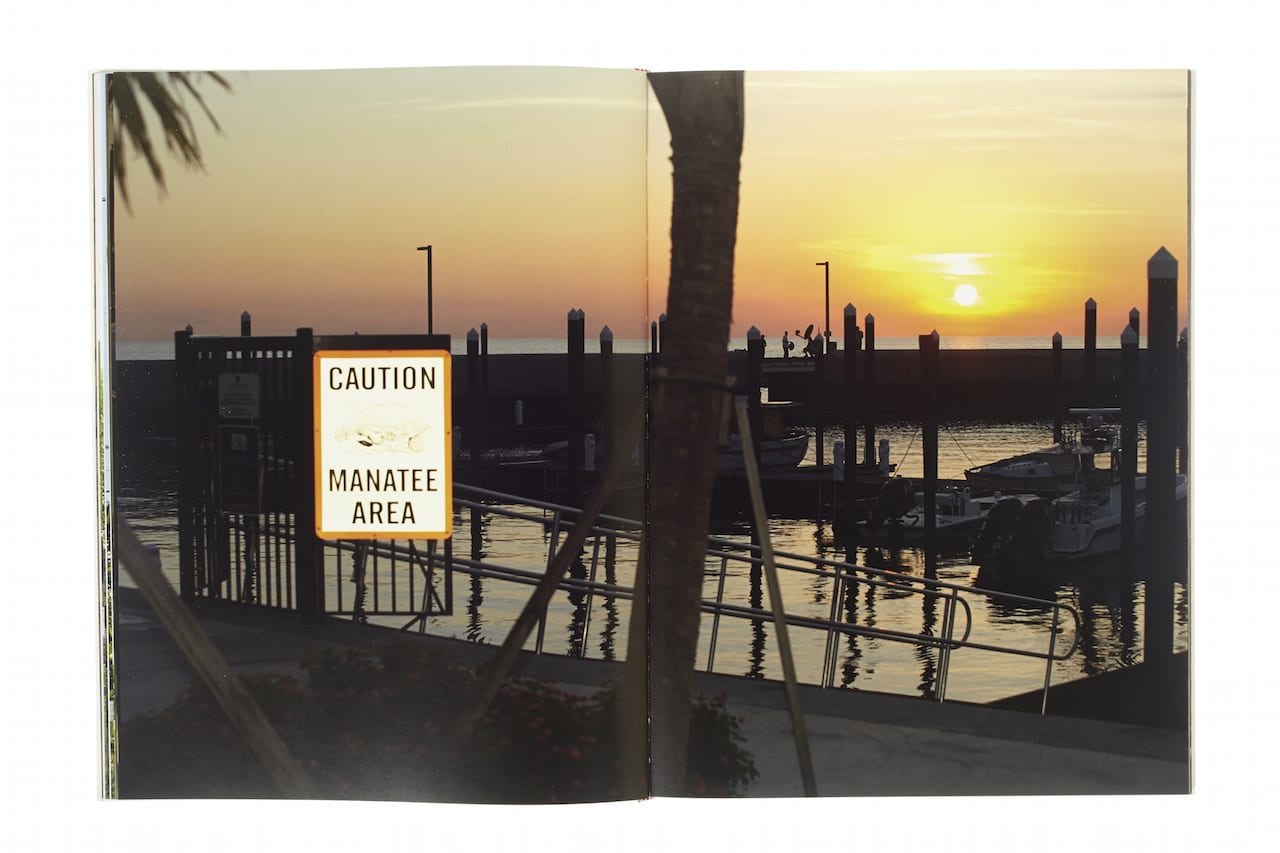

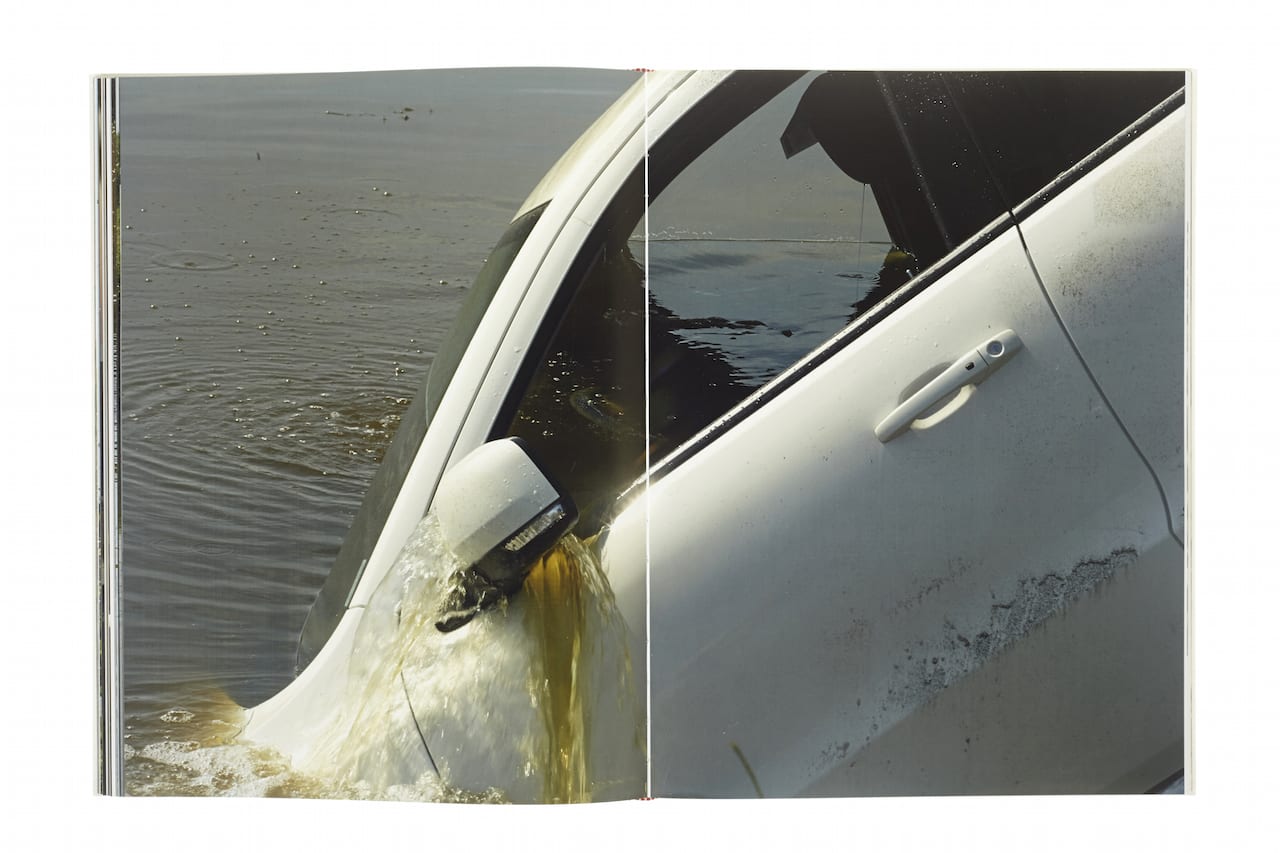

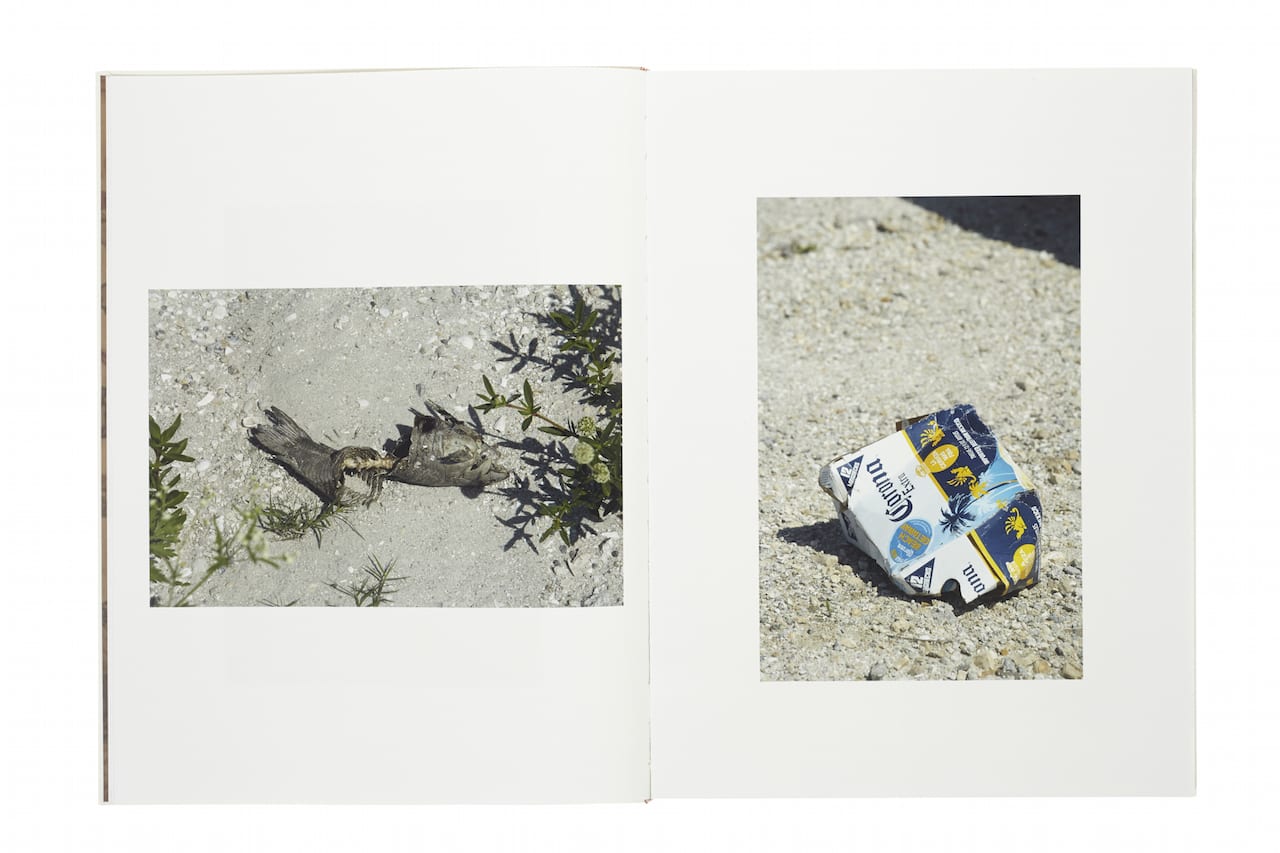

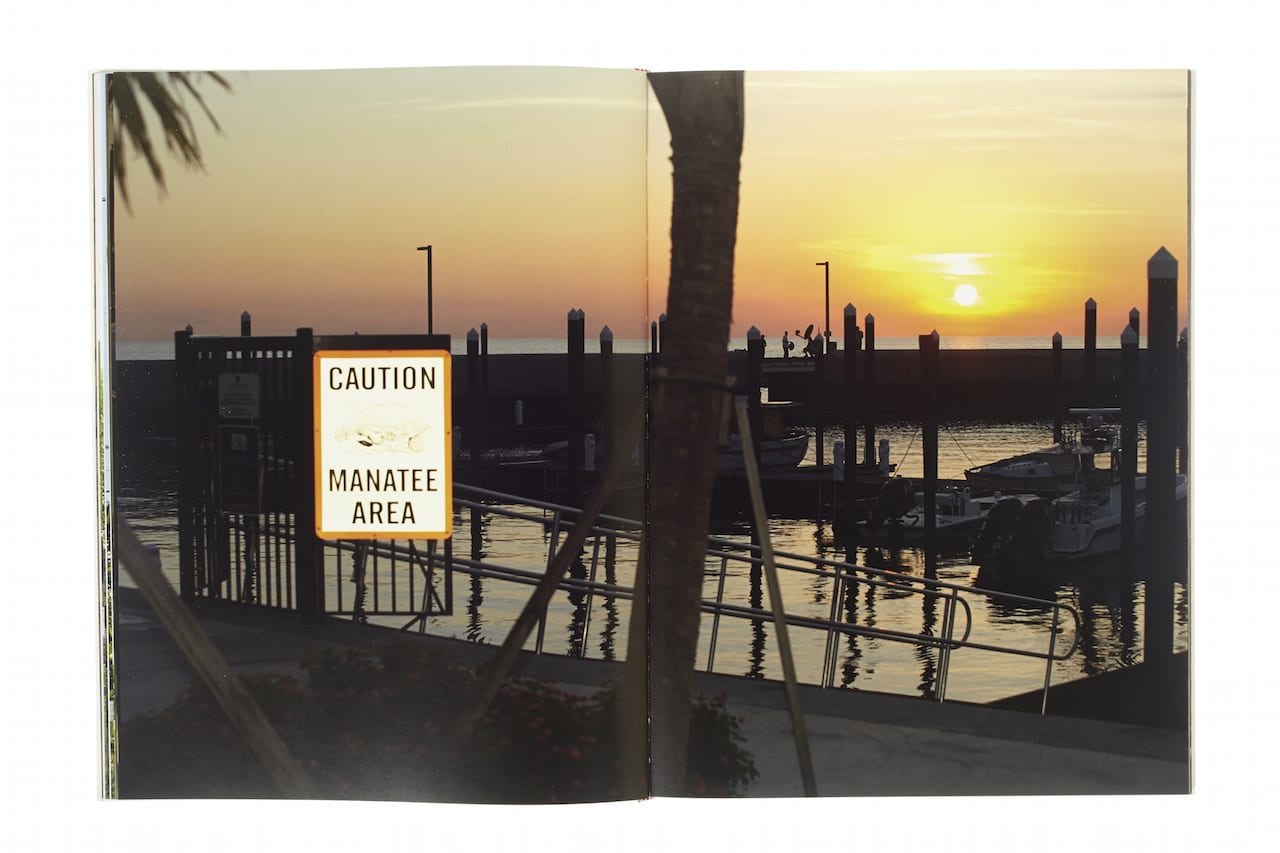

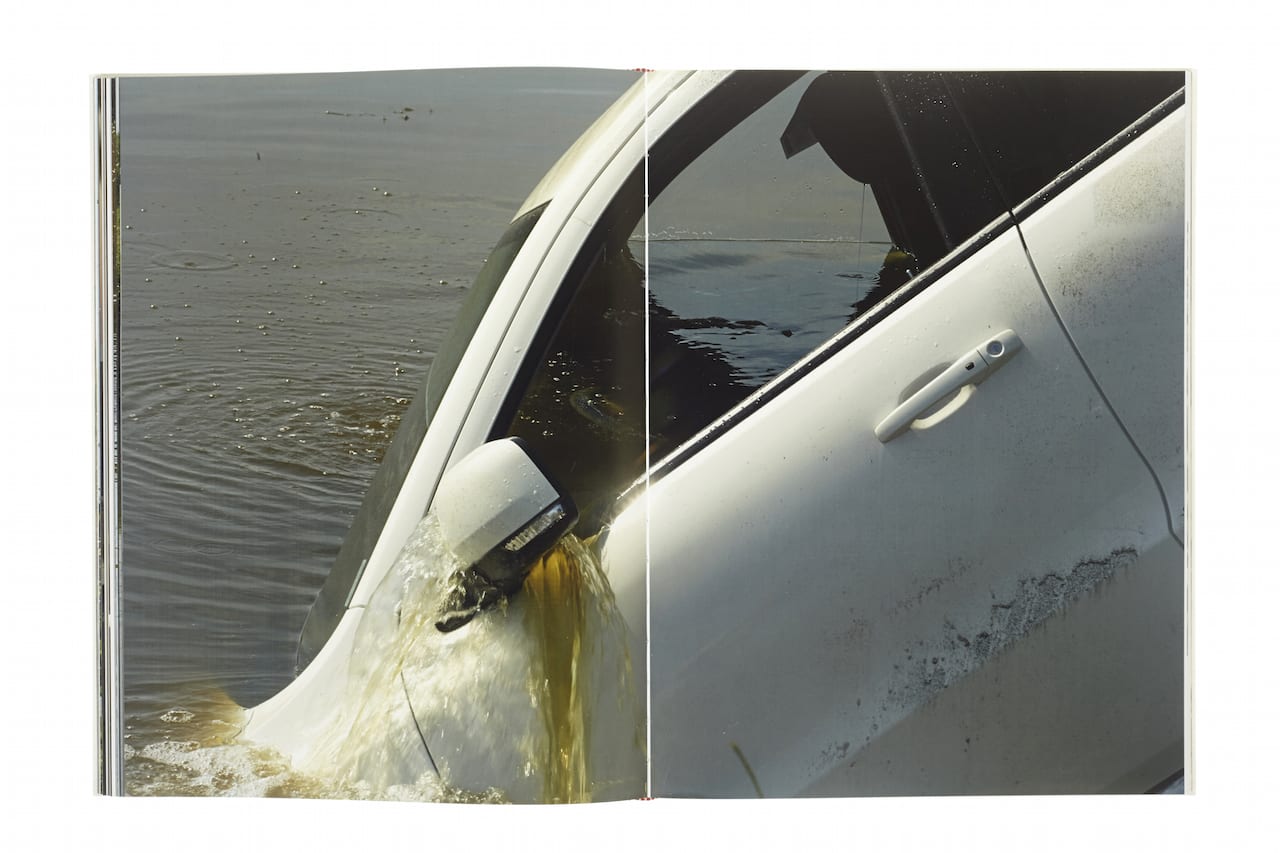

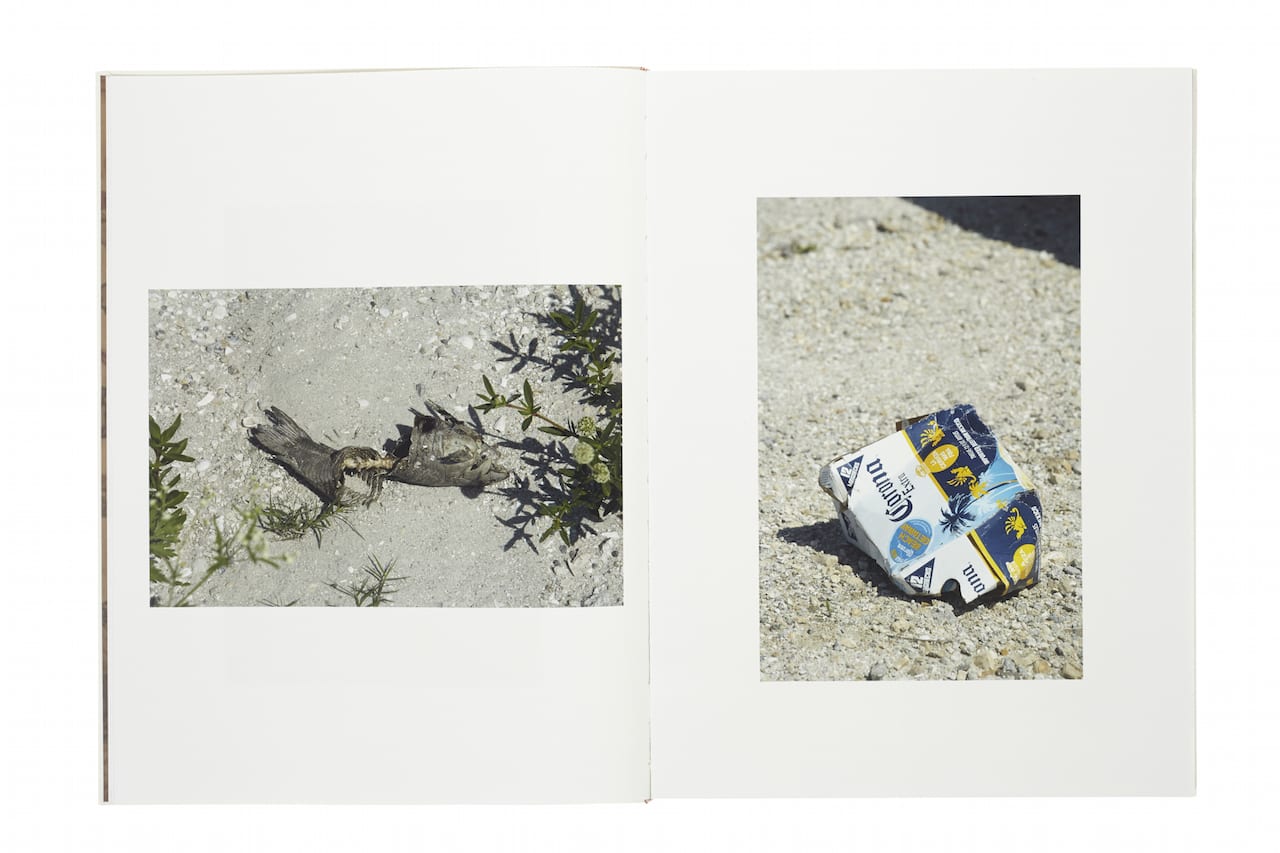

The second image in Sacrifice Your Body comes as more of a surprise – a photograph of a dank stretch of water with a partially submerged plastic bag, itʼs worlds away from humour or glamour. From there on, things take a turn for the odder. Pictures of a dead fish and discarded beer packaging segue into apparently unremarkable, technically questionable full-page bleeds of a white car driving through farmland, a poorly lit bank interior, and downright cheesy, badly exposed photos of a fishing harbour at sunset.

Image © Roe Ethridge

Next follows a blank spread, then the book resumes something more like business as usual, with Ethridgeʼs signature mix of glossy and tarnished imagery, the language of commercial photography mixed with seemingly random pictures of objects with little obvious photogenic appeal. It ends with a pixellated shot of a house taken from Google Maps. Ethridge is reluctant to do so, but eventually concedes there is “a risk involved” in including the apparently naive images.

But doing so continues what heʼs been practising all along, he says, creating a “synthetic photography” that combines art and commerce, the polished and the raw, and now the crafted with the apparently inept. “Iʼm interested in bringing everything in,” he says. “Itʼs a collection of disparate parts to make a more ‘everything pizzaʼ, to try to bring the whole world in.

Like Juergen Teller, he shoots both commercial and editorial (for the likes of Kenzo, Self Service, Acne Paper and W) alongside his own artwork, and has been shortlisted for the Deutsche Börse Photography Prize (in 2011, alongside Elad Lassry, who heʼs often cited with as evidence of a new trend for dry conceptualism). The Deutsche Börse organisers described his work as follows: “Blurring the boundaries of the commercial with the editorial, and the mundane with the highbrow, Ethridge’s conceptual approach to photography is a playful attack on the traditions and conventions of the medium itself.”

The second image in Sacrifice Your Body comes as more of a surprise – a photograph of a dank stretch of water with a partially submerged plastic bag, itʼs worlds away from humour or glamour. From there on, things take a turn for the odder. Pictures of a dead fish and discarded beer packaging segue into apparently unremarkable, technically questionable full-page bleeds of a white car driving through farmland, a poorly lit bank interior, and downright cheesy, badly exposed photos of a fishing harbour at sunset.

Next follows a blank spread, then the book resumes something more like business as usual, with Ethridgeʼs signature mix of glossy and tarnished imagery, the language of commercial photography mixed with seemingly random pictures of objects with little obvious photogenic appeal. It ends with a pixellated shot of a house taken from Google Maps. Ethridge is reluctant to do so, but eventually concedes there is “a risk involved” in including the apparently naive images.

But doing so continues what heʼs been practising all along, he says, creating a “synthetic photography” that combines art and commerce, the polished and the raw, and now the crafted with the apparently inept. “Iʼm interested in bringing everything in,” he says. “Itʼs a collection of disparate parts to make a more ‘everything pizzaʼ, to try to bring the whole world in.

“The beauty of the first half of the book is that it was shot on a crazy trip down to Florida where my mother grew up,” he adds. “I just needed to go fast and get a whole bunch of stuff… Itʼs a juxtaposition of these two styles. This kind of very casual style, in long-form chronological order, juxtaposed against something that uses seduction in a different way.”

This personal connection and the apparently amateurish style evoke a kind of family album, but while Ethridge wasnʼt thinking of that – he was thinking more about Daido Moriyama and the arebureboke style used in confident, full- page bleeds, he says – this is an intimate book, inspired by and shot through with references to his mother. The Google Maps screengrab at the end of the book shows the house he grew up in from age 10 to 18, for example, while the canal sequence references the freedom and the danger of learning to drive as a teen.

Spread from Sacrifice Your Body © Roe Ethridge, courtesy MACK Books

Spread from Sacrifice Your Body © Roe Ethridge, courtesy MACK Books

“It was styled after [his childhood home], but is a much more contemporary, ugly, mishmash of things,” says Ethridge. “It was the idea of an Odalisque figure, who could occupy some place between mother and lover in a weird space where adolescent desire takes place. Sheʼs not in a college dorm, not in an apartment, sheʼs in a particular place.”

Even the ugly typography which recurs throughout the book is inspired by Ethridgeʼs early life – expertly styled by a graphic designer friend, it pays homage to the gnarly graphics of his teenage surfing posters. “I thought it was funny to have this expert-level designer working with trashy style,” he says. “But also these posters are part of who I am – a middle- class suburban boy, now a 45-year-old man. And bringing in low culture, it lets some life into the room. It causes problems, and this is nice.”

The title, meanwhile, is a phrase local mums used to bellow from the sidelines at American football matches. Ethridgeʼs mother claims she never shouted it, but he clearly remembers hearing it, and it became a family catchphrase anyway. The phrase also reminds him of his mother because of their shared love of the sport, he adds – which provides another recurring theme, including a grinning skeleton that appears twice in the book wearing a cap emblazoned with the words ‘Florida State Seminolesʼ, the local university team, along with various images of footballs.

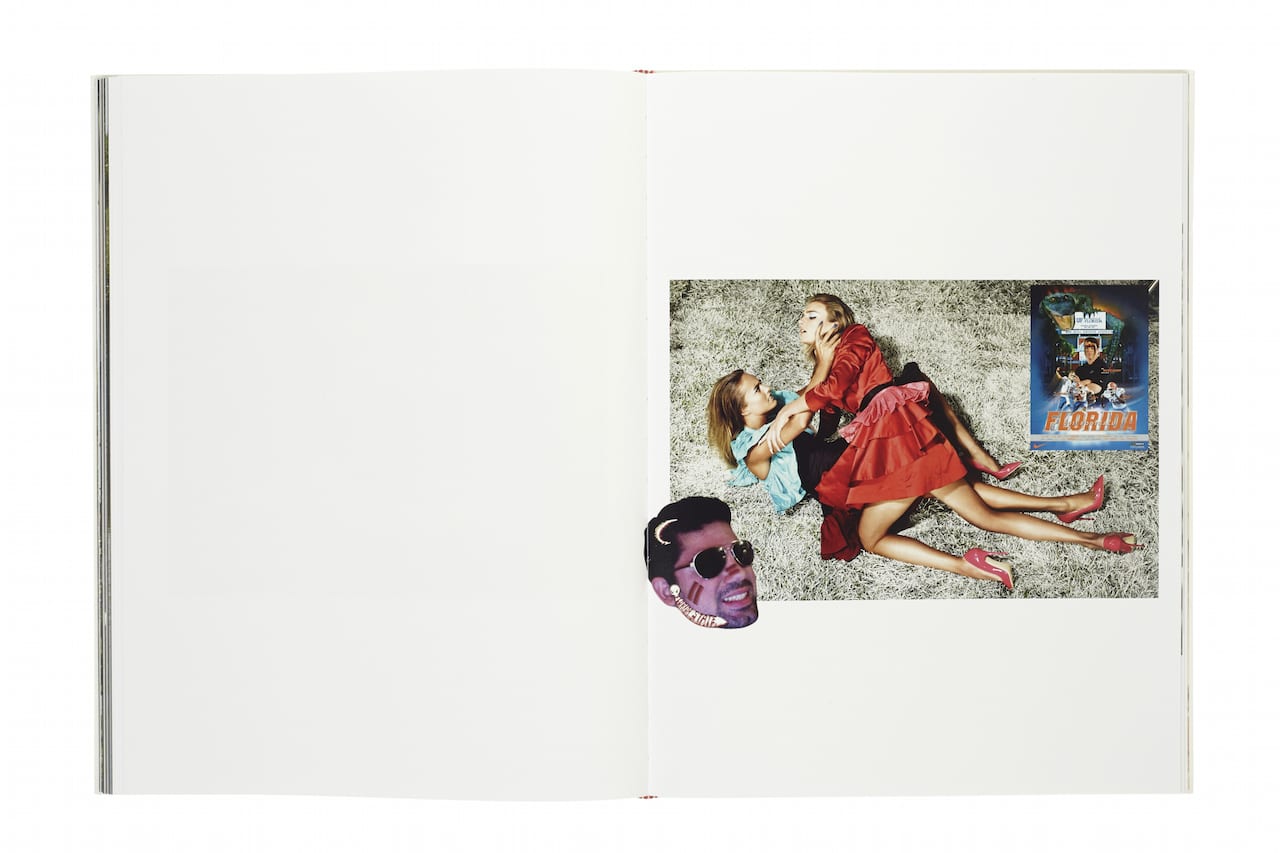

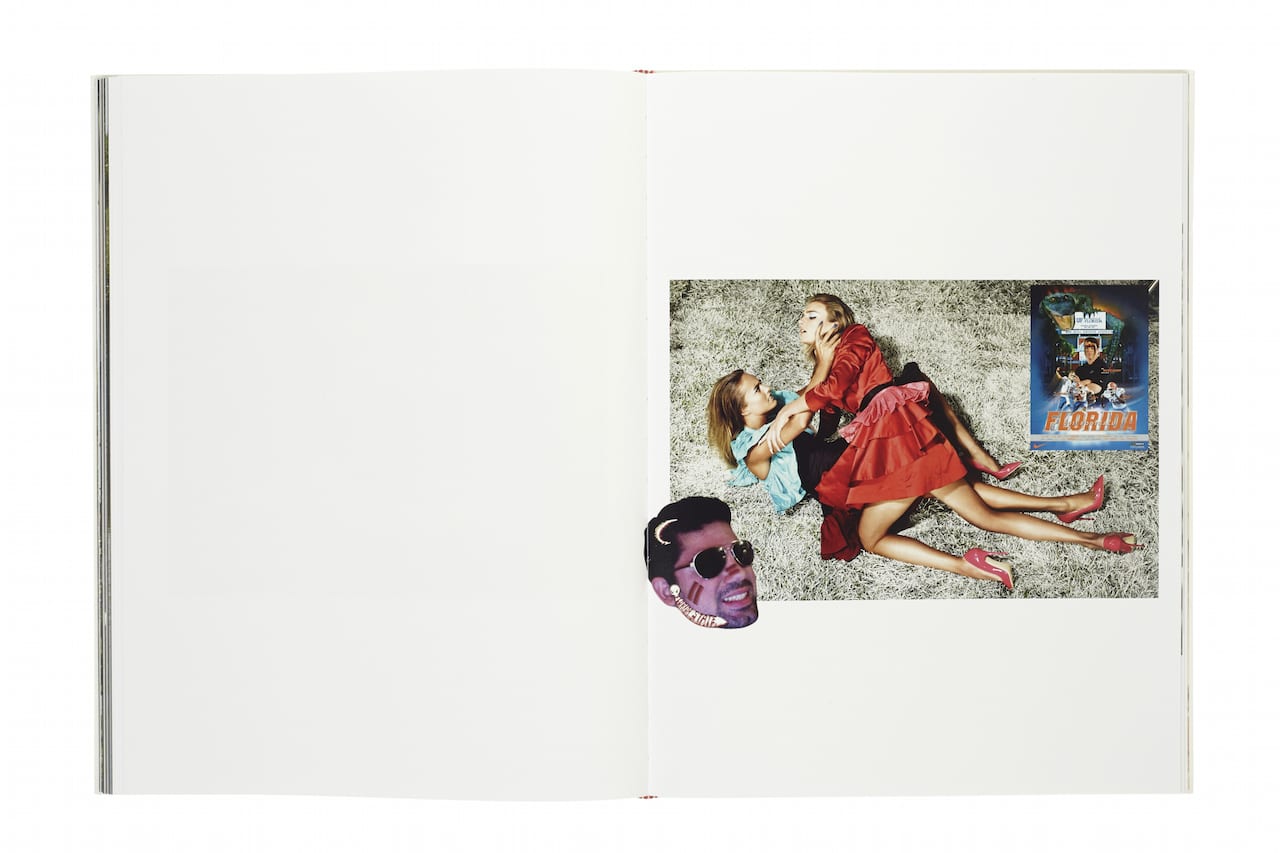

An outtake from a shoot for W magazine showing two models grappling on the ground, meanwhile, is embellished with two images taken from an American football blog – one showing a man crudely Photoshopped with Florida State team colours, the other mockingly turning an opponent into a masked wrestler. “I spend a lot of time procrastinating on sites about American football,” laughs Ethridge. “People had created these handmade, crafty things I felt so inspired by. One of the images shows a picture defaced by a Florida State fan – itʼs deeply embedded, I have no idea if someone with no interest in football would get that.”

By juxtaposing these images with the fighting women, Ethridge emphasises a sense of rivalry – and the inspiration for the W shoot was the sense of competition that sometimes springs up between models, he says. Itʼs tempting to read this as a comment on American capitalism more generally, and some have interpreted Ethridgeʼs book as a critique of contemporary values – his publisher Mack Books, for example, claims it is “a lucid undermining of veracity and morality and the ingrained materiality that underpins American life”.

Image © Roe Ethridge

“The humour is something I like to get to when I can in a commissioned shoot because itʼs fun and makes sense to me, but I can certainly say itʼs not politically motivated. Itʼs not a protest. Thatʼs like the kiss and slap, attraction and revulsion. Iʼm trying to deal with that.

“Iʼve always been interested in fashion – I assisted a catalogue photographer in Atlanta [when he first graduated] and people in New York. Itʼs a place that loves fresh blood, so there were lots of opportunities in editorial that meant I could pay the rent. I worked out that if I brought in $4000 a month I could pay the rent, and feed myself, and do my art. But if I have a brilliant idea on a shoot, the best image Iʼve made all year, I donʼt want it to vanish into an outtake and never be seen.

“I’m interested in that divide between Pictorialism [and the rest of photography], where it goes onto this Stieglitz-like high road [into high art],” he adds. “Man Ray was the highest-paid photographer in his lifetime.”

For Ethridge, straddling these various worlds embraces photographyʼs full potential, opening it up to everything that can be done rather than closing it down according to artificial boundaries. He likes the idea that the artist can adopt multiple voices, while retaining his or her own style, he says, and adds that the same thing happens on commercial studio shoots, when the photographer has to find the strength to be himself while working with very large crews.

Spread from Sacrifice Your Body © Roe Ethridge, courtesy MACK Books

Spread from Sacrifice Your Body © Roe Ethridge, courtesy MACK Books

This idea is explored in the sequencing in Sacrifice Your Body – a shot of packet noodles is followed by the Chanel logo, for example, linking the curving C shapes that can be seen in both. A grubby yellow phone against a white marble background is followed by a yellow traffic-light box and then a picture of a model in a blouse with yellow dots, talking on a white phone. Ethridge doesnʼt think about those connections when heʼs shooting, but says he realises theyʼre there when heʼs editing – and for him they embody the idea of the ‘fugueʼ.

“For the last 10 years or so I have been interested in how images could function as fugue,” he explains on the website of his Berlin gallery, Capitain Petzel, which showed prints from Sacrifice Your Body in a solo show back in 2014.

“I was initially drawn to the idea as it referred to the medical condition of the ‘fugue state’… prone to long-term amnesia, usually combined with far-flung travel. In Walker Percy’s book The Last Gentleman, the protagonist is constantly going into a fugue state and awaking from his amnesia to find he’s no longer in New York City but on a historic Civil War battlefield in Virginia, hundreds of miles away. I related to this in my work as a way to discover new images without an over-wrought thesis or a predetermined subject matter.

Image © Roe Ethridge

“I wanted to escape the seduction of ‘objectivityʼ,” he tells me. “German photography [and the typologies of the Düsseldorf school] seemed so smart, like you could get such an intellectual charge from them, and that overcast light was really ominous. I wanted to be that, but Iʼm not German. I had to separate myself from the seduction of following in that tradition.”

Roe Ethridge spoke at The Platform at Paris Photo at 6.45pm on 9 November; copies of Sacrifice Your Body are available at the MACK stand at Paris Photo https://programme.parisphoto.com/en/platform.htm Sacrifice Your Body is published by MACK Books and retails at £40 www.mackbooks.co.uk

This personal connection and the apparently amateurish style evoke a kind of family album, but while Ethridge wasnʼt thinking of that – he was thinking more about Daido Moriyama and the arebureboke style used in confident, full- page bleeds, he says – this is an intimate book, inspired by and shot through with references to his mother. The Google Maps screengrab at the end of the book shows the house he grew up in from age 10 to 18, for example, while the canal sequence references the freedom and the danger of learning to drive as a teen.

“It was styled after [his childhood home], but is a much more contemporary, ugly, mishmash of things,” says Ethridge. “It was the idea of an Odalisque figure, who could occupy some place between mother and lover in a weird space where adolescent desire takes place. Sheʼs not in a college dorm, not in an apartment, sheʼs in a particular place.”

Even the ugly typography which recurs throughout the book is inspired by Ethridgeʼs early life – expertly styled by a graphic designer friend, it pays homage to the gnarly graphics of his teenage surfing posters. “I thought it was funny to have this expert-level designer working with trashy style,” he says. “But also these posters are part of who I am – a middle- class suburban boy, now a 45-year-old man. And bringing in low culture, it lets some life into the room. It causes problems, and this is nice.”

The title, meanwhile, is a phrase local mums used to bellow from the sidelines at American football matches. Ethridgeʼs mother claims she never shouted it, but he clearly remembers hearing it, and it became a family catchphrase anyway. The phrase also reminds him of his mother because of their shared love of the sport, he adds – which provides another recurring theme, including a grinning skeleton that appears twice in the book wearing a cap emblazoned with the words ‘Florida State Seminolesʼ, the local university team, along with various images of footballs.

An outtake from a shoot for W magazine showing two models grappling on the ground, meanwhile, is embellished with two images taken from an American football blog – one showing a man crudely Photoshopped with Florida State team colours, the other mockingly turning an opponent into a masked wrestler. “I spend a lot of time procrastinating on sites about American football,” laughs Ethridge. “People had created these handmade, crafty things I felt so inspired by. One of the images shows a picture defaced by a Florida State fan – itʼs deeply embedded, I have no idea if someone with no interest in football would get that.”

By juxtaposing these images with the fighting women, Ethridge emphasises a sense of rivalry – and the inspiration for the W shoot was the sense of competition that sometimes springs up between models, he says. Itʼs tempting to read this as a comment on American capitalism more generally, and some have interpreted Ethridgeʼs book as a critique of contemporary values – his publisher Mack Books, for example, claims it is “a lucid undermining of veracity and morality and the ingrained materiality that underpins American life”.

“The humour is something I like to get to when I can in a commissioned shoot because itʼs fun and makes sense to me, but I can certainly say itʼs not politically motivated. Itʼs not a protest. Thatʼs like the kiss and slap, attraction and revulsion. Iʼm trying to deal with that.

“Iʼve always been interested in fashion – I assisted a catalogue photographer in Atlanta [when he first graduated] and people in New York. Itʼs a place that loves fresh blood, so there were lots of opportunities in editorial that meant I could pay the rent. I worked out that if I brought in $4000 a month I could pay the rent, and feed myself, and do my art. But if I have a brilliant idea on a shoot, the best image Iʼve made all year, I donʼt want it to vanish into an outtake and never be seen.

“I’m interested in that divide between Pictorialism [and the rest of photography], where it goes onto this Stieglitz-like high road [into high art],” he adds. “Man Ray was the highest-paid photographer in his lifetime.”

For Ethridge, straddling these various worlds embraces photographyʼs full potential, opening it up to everything that can be done rather than closing it down according to artificial boundaries. He likes the idea that the artist can adopt multiple voices, while retaining his or her own style, he says, and adds that the same thing happens on commercial studio shoots, when the photographer has to find the strength to be himself while working with very large crews.

This idea is explored in the sequencing in Sacrifice Your Body – a shot of packet noodles is followed by the Chanel logo, for example, linking the curving C shapes that can be seen in both. A grubby yellow phone against a white marble background is followed by a yellow traffic-light box and then a picture of a model in a blouse with yellow dots, talking on a white phone. Ethridge doesnʼt think about those connections when heʼs shooting, but says he realises theyʼre there when heʼs editing – and for him they embody the idea of the ‘fugueʼ.

“For the last 10 years or so I have been interested in how images could function as fugue,” he explains on the website of his Berlin gallery, Capitain Petzel, which showed prints from Sacrifice Your Body in a solo show back in 2014.

“I was initially drawn to the idea as it referred to the medical condition of the ‘fugue state’… prone to long-term amnesia, usually combined with far-flung travel. In Walker Percy’s book The Last Gentleman, the protagonist is constantly going into a fugue state and awaking from his amnesia to find he’s no longer in New York City but on a historic Civil War battlefield in Virginia, hundreds of miles away. I related to this in my work as a way to discover new images without an over-wrought thesis or a predetermined subject matter.

“I wanted to escape the seduction of ‘objectivityʼ,” he tells me. “German photography [and the typologies of the Düsseldorf school] seemed so smart, like you could get such an intellectual charge from them, and that overcast light was really ominous. I wanted to be that, but Iʼm not German. I had to separate myself from the seduction of following in that tradition.”

Roe Ethridge spoke at The Platform at Paris Photo at 6.45pm on 9 November; copies of Sacrifice Your Body are available at the MACK stand at Paris Photo https://programme.parisphoto.com/en/platform.htm Sacrifice Your Body is published by MACK Books and retails at £40 www.mackbooks.co.uk

This article was first published in the March 2014 issue of BJP.