Bilbao-based photographer Vicente Paredes has been boxing for 10 years, training in his local gym under retired Congolese pro Pedro Massamba. The two have shared many stories and over time Massamba’s tales of his homeland piqued Paredes’ interest, eventually giving him “the urge to visit”.

Once he decided to make the trip, his instructor put him in touch with friends in the south of the country and its capital, Kinshasa. But on arrival Paredes soon became fascinated with the villages outside the city, and the lives of the children who inhabited them, returning to the country several times.

“I followed Massamba’s advice and went to the Democratic Republic of Congo, which is the poorest country in the world,” he says. “I took pictures of village kids during school hours; they are shown working, helping their parents, which is natural in that context. [But] they would rather go to school.”

At the same time another friend recommended Paredes go to a pony riding tournament in Spain, to capture the pressure the child participants are subjected to. They were “crying and stressed out” says Paredes and, though very well-dressed and materially privileged, they were suffering. “They [the adults] talk about sport but it is about having a competitive spirit,” says Paredes. “Whether you’re rich or poor, you are creating a little capitalistic monster.”

From the series Pony Congo © Vicente Paredes

While his first trip to Congo was exploratory, for the second he had a clear vision in mind and his boxing instructor’s words ringing in his ears. “In Spain people are whining for no reason,” Massamba had told him. “I should take them all to see the Congo. Then they would see what crisis means.” Paredes remembers photographing a child hacking tree trunks with a machete, for example, and says: “I spent one hour with him. He cut 20 trunks; he must have been 12 years old.”

The two projects – seemingly so different, yet so similar – came together and, with de Middel’s input as head curator of Lagos Photo Festival 2015, were exhibited side-by-side as a hard-hitting series titled Pony Congo. The two sets of portraits suggest oppositions such as comfort and discomfort, self-consciousness and apparently freer lives, as well as trickier concepts such as perceived happiness and the way adults impose their values on the young.

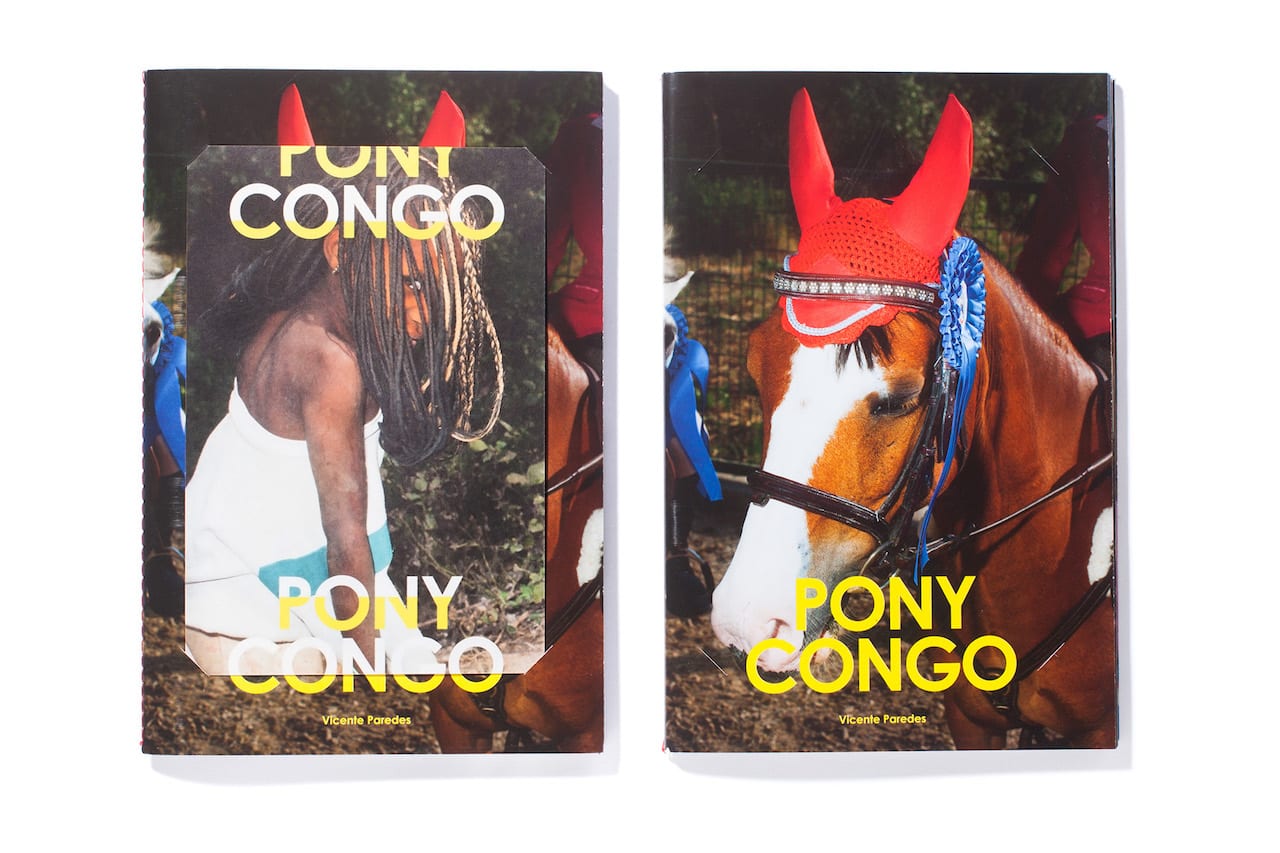

The exhibition was well-received in Lagos and the series became de Middel’s first publication in her new venture This Book is True in 2016. “The disparity in income in Nigeria is atrocious; people there told me they loved Pony Congo,” says Paredes. “They also thought the pony pictures were very exotic.” The book went on to be included in the Best Books of the Year shortlist at Fotobookfestival Kassel, and the Author Book Award shortlist at the Rencontres d’Arles.

From the series Pony Congo © Vicente Paredes

From the series Pony Congo © Vicente Paredes

“I grew up reading music fanzines and stuff related to class warfare – the anti-system,” he says. “Our main problem, I believe, is inequality. I just hadn’t found a way [to do something about it photographically].”

He cites Bill Brandt’s The English at Home (1936) and Jacob Riis’ How the Other Half Lives (1890) as influences, though he regrets that “nowadays, it is practically impossible to change things with photographic works”. His father was also an inspiration: a salesman who worked in Cameroon for 20 years, Paredes Sr sometimes took his son on his trips.

“I don’t want to downplay the effects of the economic crisis in Spain, but the way some people complained about the small stuff reminded me of the travels I shared with my dad,” says Paredes. “You have to see how other people live to realise that poverty is relative. Yes, the breach between the haves and have-nots is ever-increasing in Spain. But if you oppose that with the situation in Africa, the difference becomes brutal.”

From the series Pony Congo © Vicente Paredes

To emphasise his point he quotes from the book El Hambre by Argentine writer Martín Caparrós: “They now use the words ‘food safety’ instead of ‘hunger’,” he says. “It’s important to remember that hunger is the problem and we must show it without resorting to euphemism or metaphor.”

He edited the book with help from Cases and designer Natalia Troitiño, who suggested he use diptychs and quadriptychs, “like a series of blows”. The two sets of images are also separated by the papers on which they are printed, with the shots from Spain reproduced on glossy stock and the rest on a rougher material. By contrasting them in this way, Paredes felt there was no need for extra captions.

Aesthetics play an important role in how the two sets of images come across – the Spanish portraits seem flashy, in both senses of the word, while the images from Congo are oversaturated, though in fact both were made using cross-polarisation. “I shot the pictures in Spain with the sort of polarised light filters that are used to reduce shine when photographing works of art,” says Paredes. “Then I used the same technique to take pictures of smiling children in Africa.”

The smiles reflect the way the Congolese children present themselves, he adds – they are used to being photographed by wealthy tourists and always struck a pose and smiled at him, greeting him with a “Ni hao!” because most non-African visitors to the region are Chinese. By contrast, the children at the equestrian events were often wary, and Paredes felt under pressure to obscure their identities.

Once he decided to make the trip, his instructor put him in touch with friends in the south of the country and its capital, Kinshasa. But on arrival Paredes soon became fascinated with the villages outside the city, and the lives of the children who inhabited them, returning to the country several times.

“I followed Massamba’s advice and went to the Democratic Republic of Congo, which is the poorest country in the world,” he says. “I took pictures of village kids during school hours; they are shown working, helping their parents, which is natural in that context. [But] they would rather go to school.”

At the same time another friend recommended Paredes go to a pony riding tournament in Spain, to capture the pressure the child participants are subjected to. They were “crying and stressed out” says Paredes and, though very well-dressed and materially privileged, they were suffering. “They [the adults] talk about sport but it is about having a competitive spirit,” says Paredes. “Whether you’re rich or poor, you are creating a little capitalistic monster.”

While his first trip to Congo was exploratory, for the second he had a clear vision in mind and his boxing instructor’s words ringing in his ears. “In Spain people are whining for no reason,” Massamba had told him. “I should take them all to see the Congo. Then they would see what crisis means.” Paredes remembers photographing a child hacking tree trunks with a machete, for example, and says: “I spent one hour with him. He cut 20 trunks; he must have been 12 years old.”

The two projects – seemingly so different, yet so similar – came together and, with de Middel’s input as head curator of Lagos Photo Festival 2015, were exhibited side-by-side as a hard-hitting series titled Pony Congo. The two sets of portraits suggest oppositions such as comfort and discomfort, self-consciousness and apparently freer lives, as well as trickier concepts such as perceived happiness and the way adults impose their values on the young.

The exhibition was well-received in Lagos and the series became de Middel’s first publication in her new venture This Book is True in 2016. “The disparity in income in Nigeria is atrocious; people there told me they loved Pony Congo,” says Paredes. “They also thought the pony pictures were very exotic.” The book went on to be included in the Best Books of the Year shortlist at Fotobookfestival Kassel, and the Author Book Award shortlist at the Rencontres d’Arles.

“I grew up reading music fanzines and stuff related to class warfare – the anti-system,” he says. “Our main problem, I believe, is inequality. I just hadn’t found a way [to do something about it photographically].”

He cites Bill Brandt’s The English at Home (1936) and Jacob Riis’ How the Other Half Lives (1890) as influences, though he regrets that “nowadays, it is practically impossible to change things with photographic works”. His father was also an inspiration: a salesman who worked in Cameroon for 20 years, Paredes Sr sometimes took his son on his trips.

“I don’t want to downplay the effects of the economic crisis in Spain, but the way some people complained about the small stuff reminded me of the travels I shared with my dad,” says Paredes. “You have to see how other people live to realise that poverty is relative. Yes, the breach between the haves and have-nots is ever-increasing in Spain. But if you oppose that with the situation in Africa, the difference becomes brutal.”

To emphasise his point he quotes from the book El Hambre by Argentine writer Martín Caparrós: “They now use the words ‘food safety’ instead of ‘hunger’,” he says. “It’s important to remember that hunger is the problem and we must show it without resorting to euphemism or metaphor.”

He edited the book with help from Cases and designer Natalia Troitiño, who suggested he use diptychs and quadriptychs, “like a series of blows”. The two sets of images are also separated by the papers on which they are printed, with the shots from Spain reproduced on glossy stock and the rest on a rougher material. By contrasting them in this way, Paredes felt there was no need for extra captions.

Aesthetics play an important role in how the two sets of images come across – the Spanish portraits seem flashy, in both senses of the word, while the images from Congo are oversaturated, though in fact both were made using cross-polarisation. “I shot the pictures in Spain with the sort of polarised light filters that are used to reduce shine when photographing works of art,” says Paredes. “Then I used the same technique to take pictures of smiling children in Africa.”

The smiles reflect the way the Congolese children present themselves, he adds – they are used to being photographed by wealthy tourists and always struck a pose and smiled at him, greeting him with a “Ni hao!” because most non-African visitors to the region are Chinese. By contrast, the children at the equestrian events were often wary, and Paredes felt under pressure to obscure their identities.

For Paredes, the sense that there is “something that is not right” is up to the viewer. “You make the deduction yourself,” he told BJP. “You have to bear in mind that the kids in my book will never meet in real life. It is the viewer who must imagine what would happen if they were to meet. Ideas such as colonialism, misery, pity and mistrust are in our minds, not in the pictures themselves.”

Pony Congo by Vicente Paredes is on show at Espace Images Vevey from 22 November-23 December https://www.images.ch/en/pony-congo-vicente-paredes/ Pony Congo by Vicente Paredes is published by This Book is True, priced €30 https://www.lademiddel.com/thisbookistrue/

A slightly different version of this article first appeared in BJP in print in February 2016, in a special issue looking at images of the wealthy. It’s available via www.thebjpshop.com