“These pictures were originally intended as a sort of ‘Fuck you’ to the Bush administration,” says Sean Hemmerle. “I never thought after he was gone we would eventually end up with someone that made him look good. They’re a ‘Fuck you’ to someone else now.”

On the morning of September 11 2001, former sergeant turned photographer Sean Hemmerle was travelling past the World Trade Centre, on his way to The New Yorker to drop off a portfolio of pictures. “Then some massive calamity interrupted my morning,” he says, wryly.

“I photographed the towers as they fell, the people at the sight, ground zero. Somehow I got in there. I guess some of those pictures ended up becoming sort of ‘iconic’, and from them I made what, to me, at that time was a tonne of money.”

The success of those photographs brought internal conflict and a sense of moral duty, says Hemmerle, as he struggled with the idea that he was profiting from the “smouldering hole in the centre of my community”. He decided that he had to follow up with something of value, but at first didn’t know what that something could be. Then it occurred to him. “I had to go to Afghanistan,” he says.

Hemmerle had been a Nuclear, Biological and Chemical Non-Commissioned Officer in Oklahoma during the Cold War, tasked with training people on what do in a chemical environment, and how to navigate mine fields. “Oklahoma is not quite Afghanistan,” he says. “I never thought I’d end up in a war zone, I thought that part of my life was over. But I had to do it.”

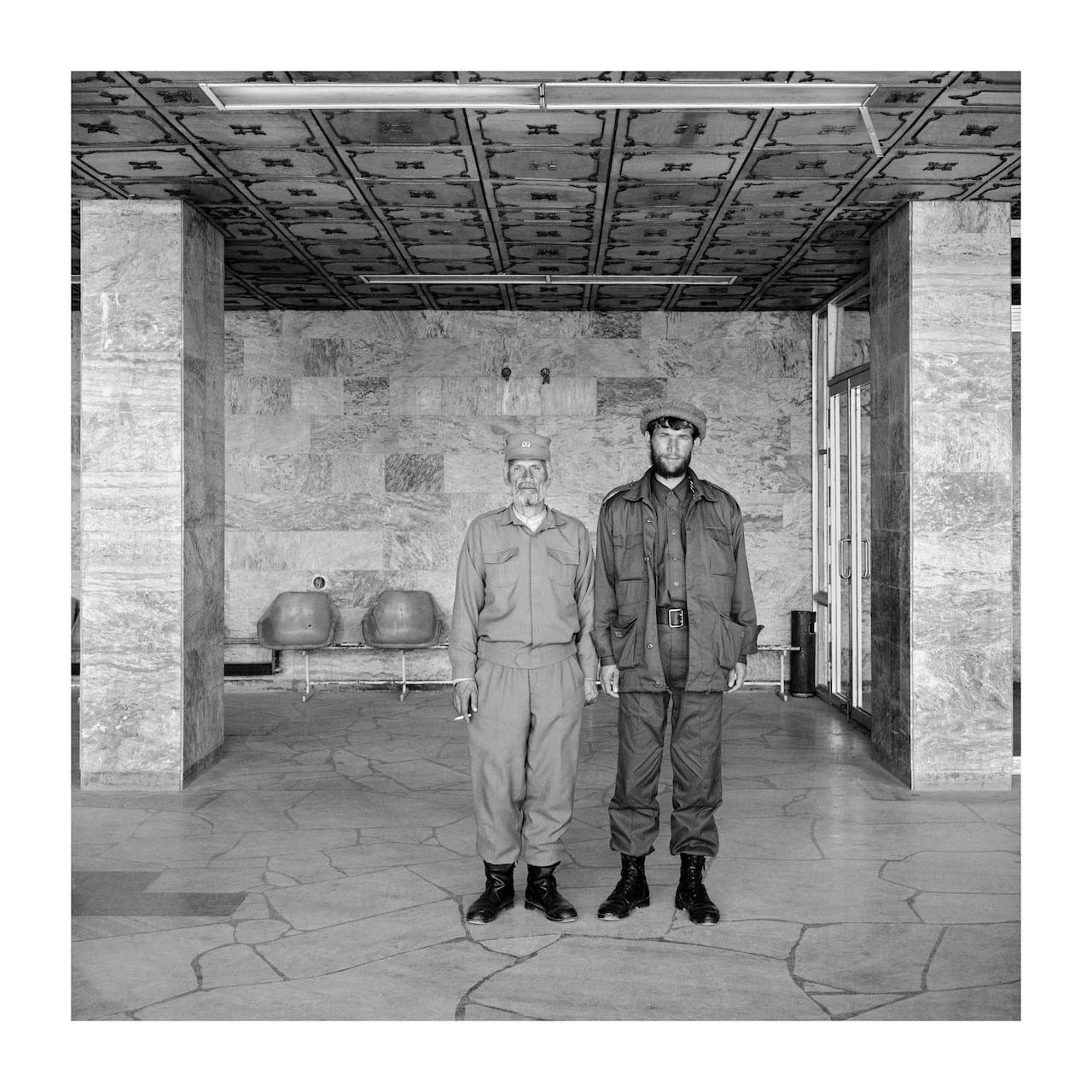

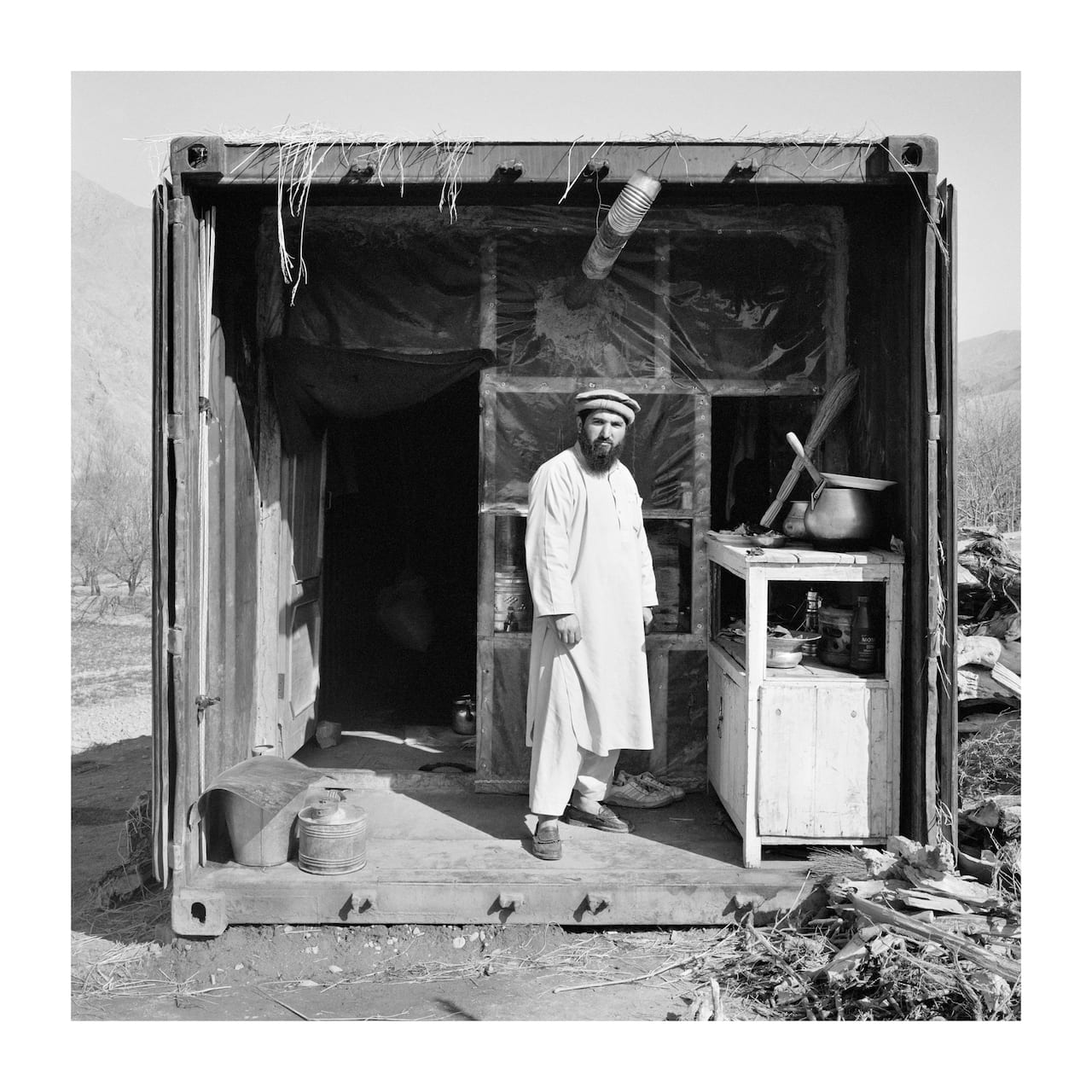

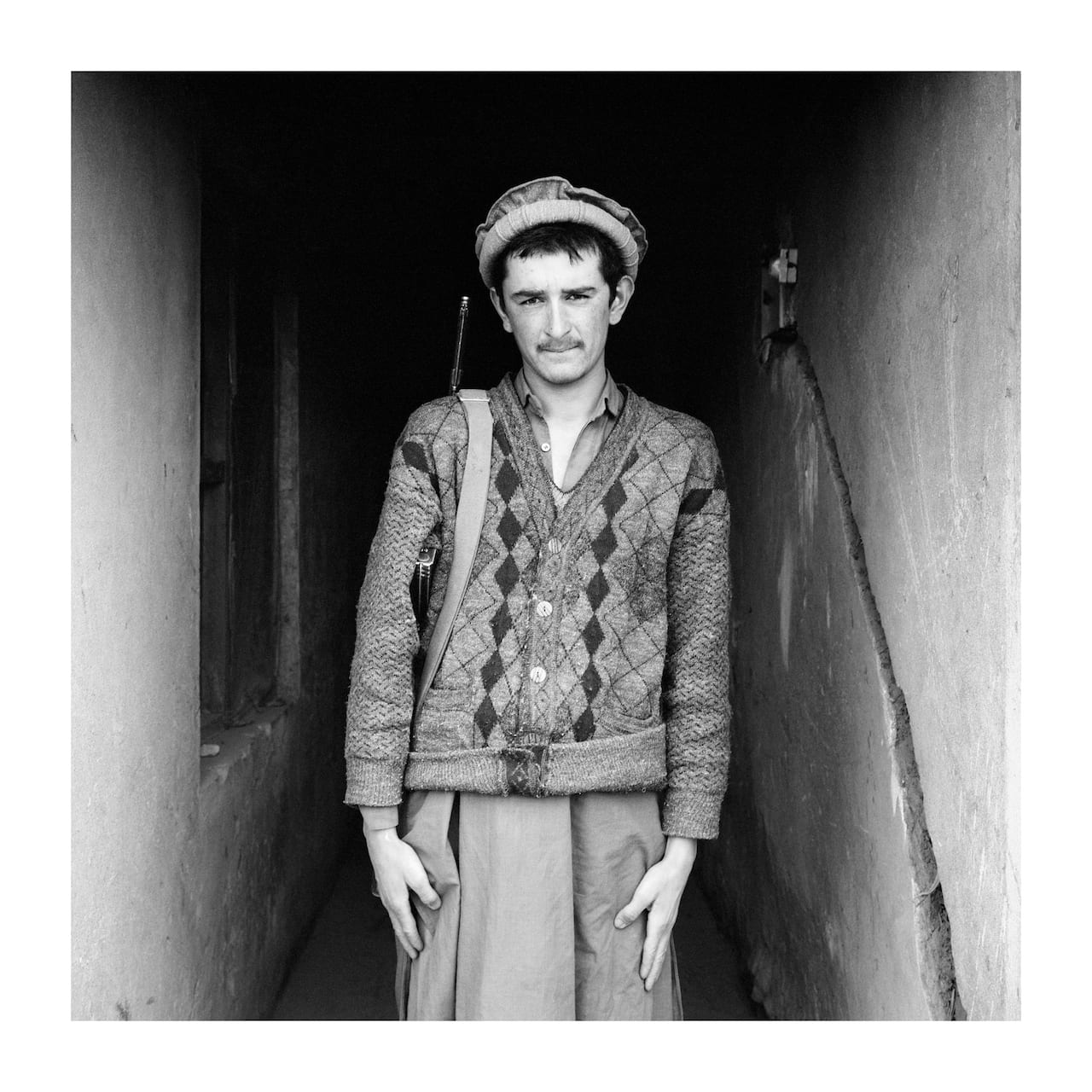

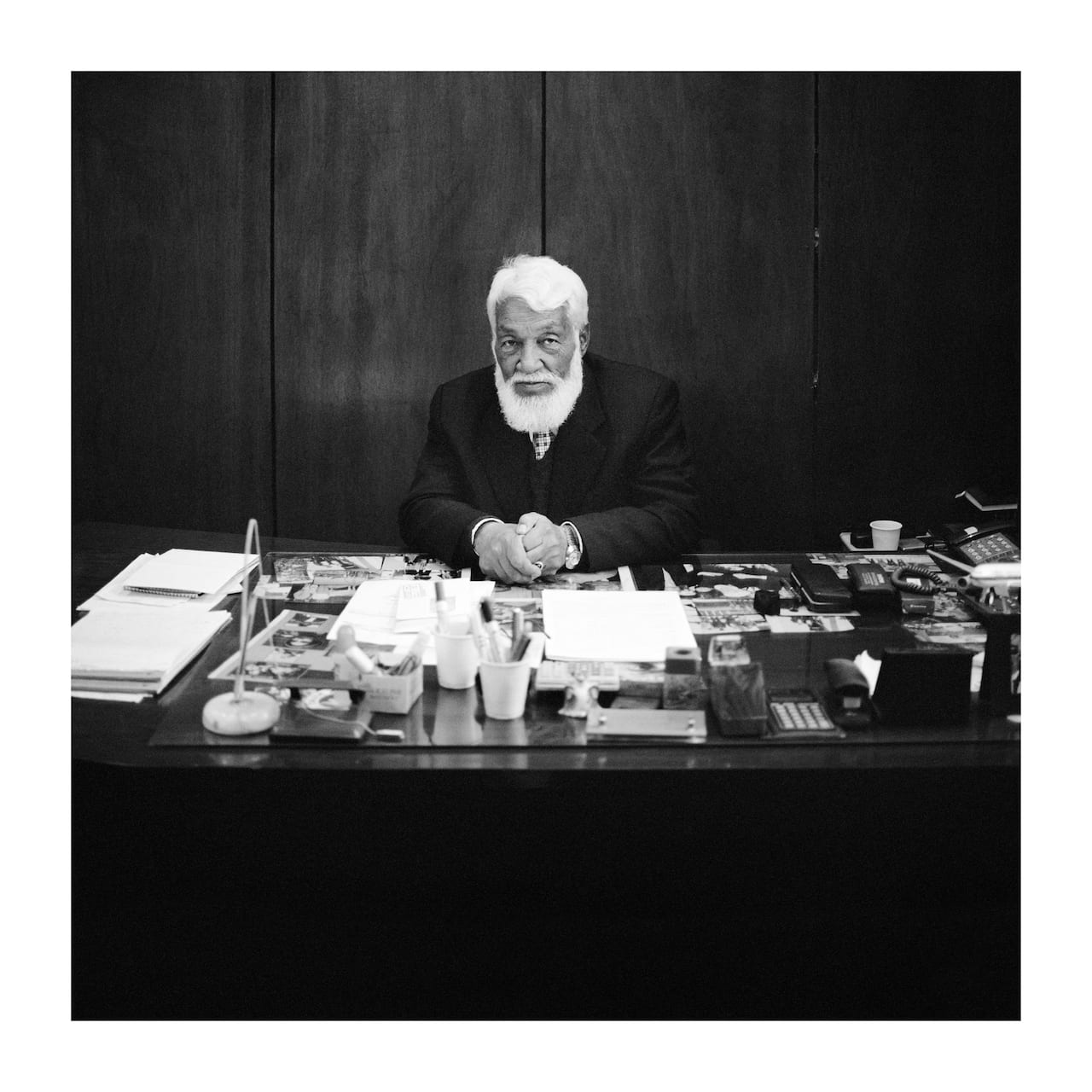

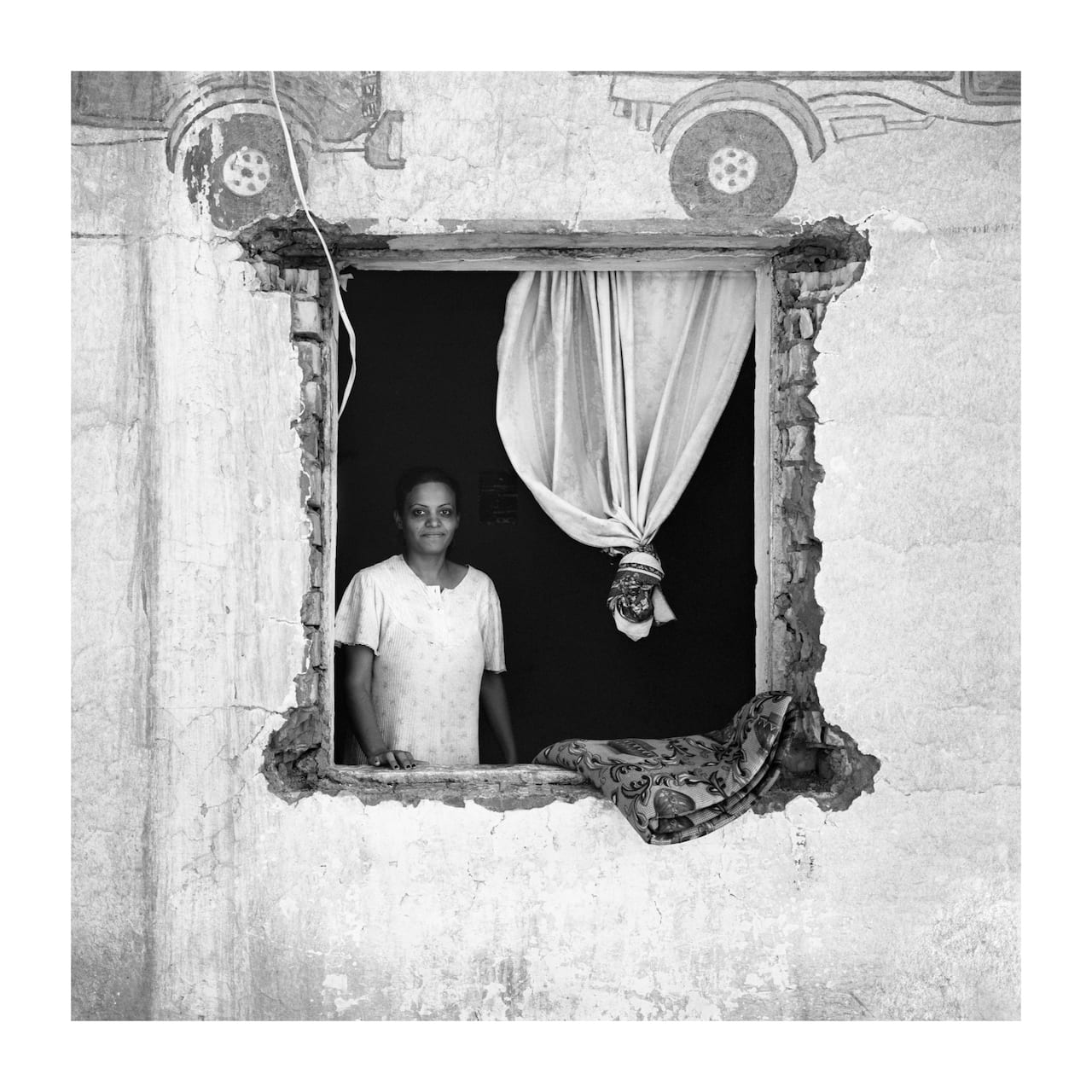

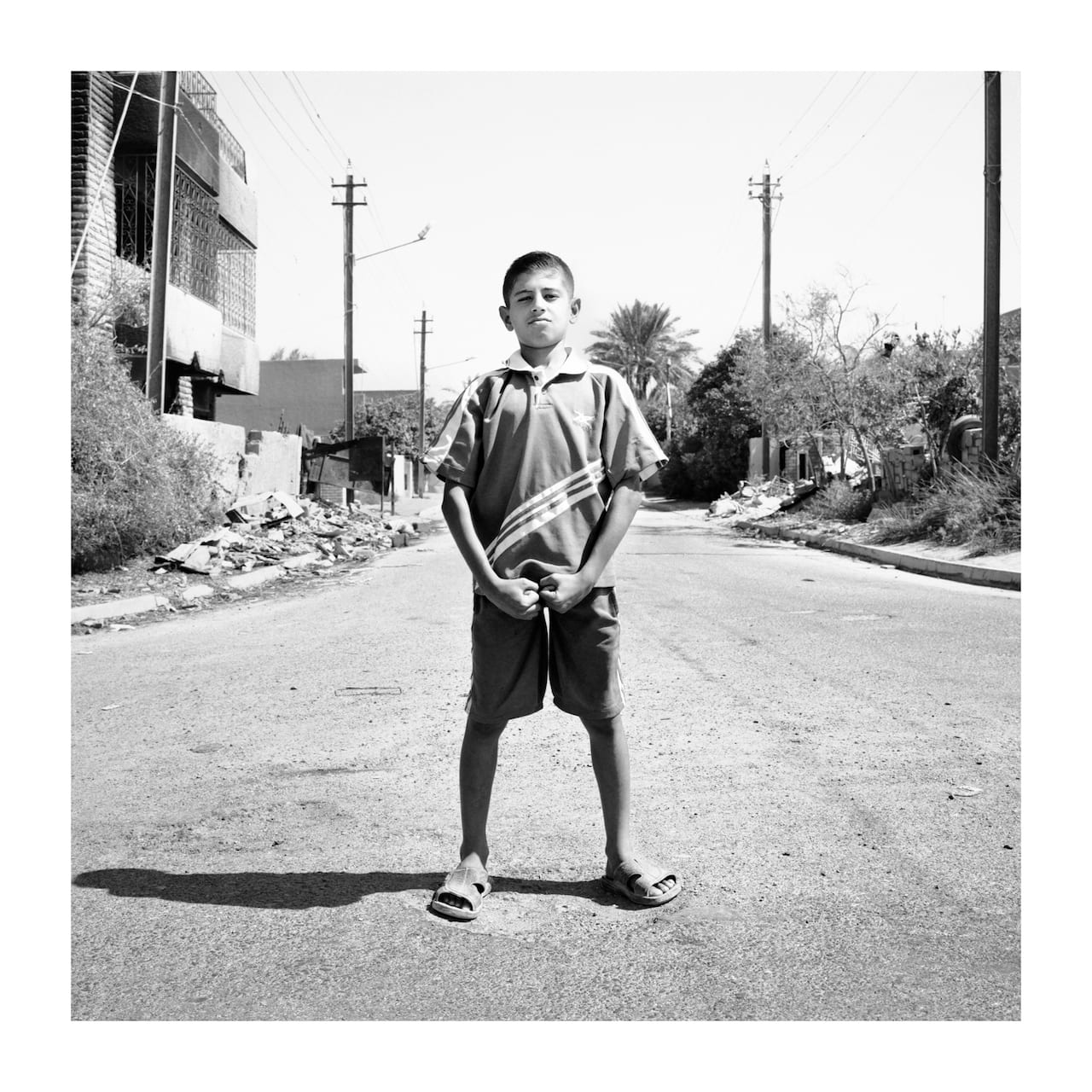

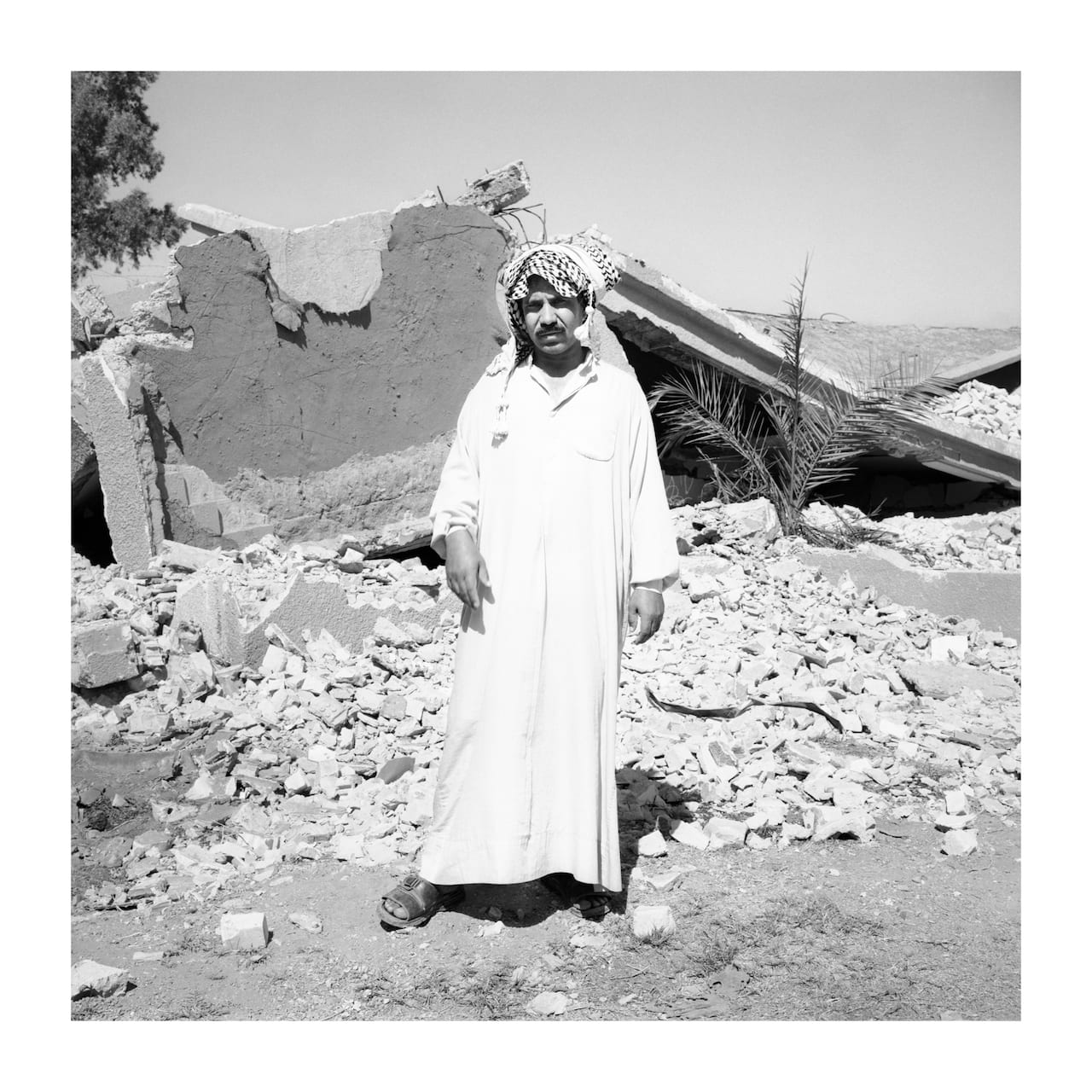

Travelling to Afghanistan and later Iraq in 2002 and 2003, he initially intended to shoot the “minefields, battlefields and surrounding architecture” he found. But he also started taking black-and-white photographs of the people he met along the way. These portraits soon took precedence. The resulting series, THEM, depicts some of the individuals that people back home were being taught to hate.

“I have never encountered the same degree of hospitality, warmth and kindness as I did in Afghanistan,” says Hemmerle. “This country, these people, were the same ones that ‘my’ country was saying we needed to ‘Bomb back to the stone age’. The broadcast from where I come from is so misinformed, myopic, and crafted to be seen and heard by our population. It sews fear.”

Subjects were not hard to come by, he says, as “people would just come up to me when they realised what I was doing and ask me to take their picture”. “As for the way I was shooting, I thought the black-and-white film felt more archival, more abstract. Those pictures would last longer and become like monuments to these people,” he says.

“I think a lot of the people I met were very much saying: ‘This is a moment in history. You and your people should see me. You should understand this’.”

Hemmerle recorded his experiences in journals and emails, and has included these observations in THEM. He talks of demolished schools and homes, of people, conversations, and survival, of the sounds of gun fire and artillery, of the smells that reminded him of Ground Zero on September 11. The writing is immediate and raw and, when placed alongside the images, paints a picture of the people and the war in these countries that was rarely shown at the time in the West.

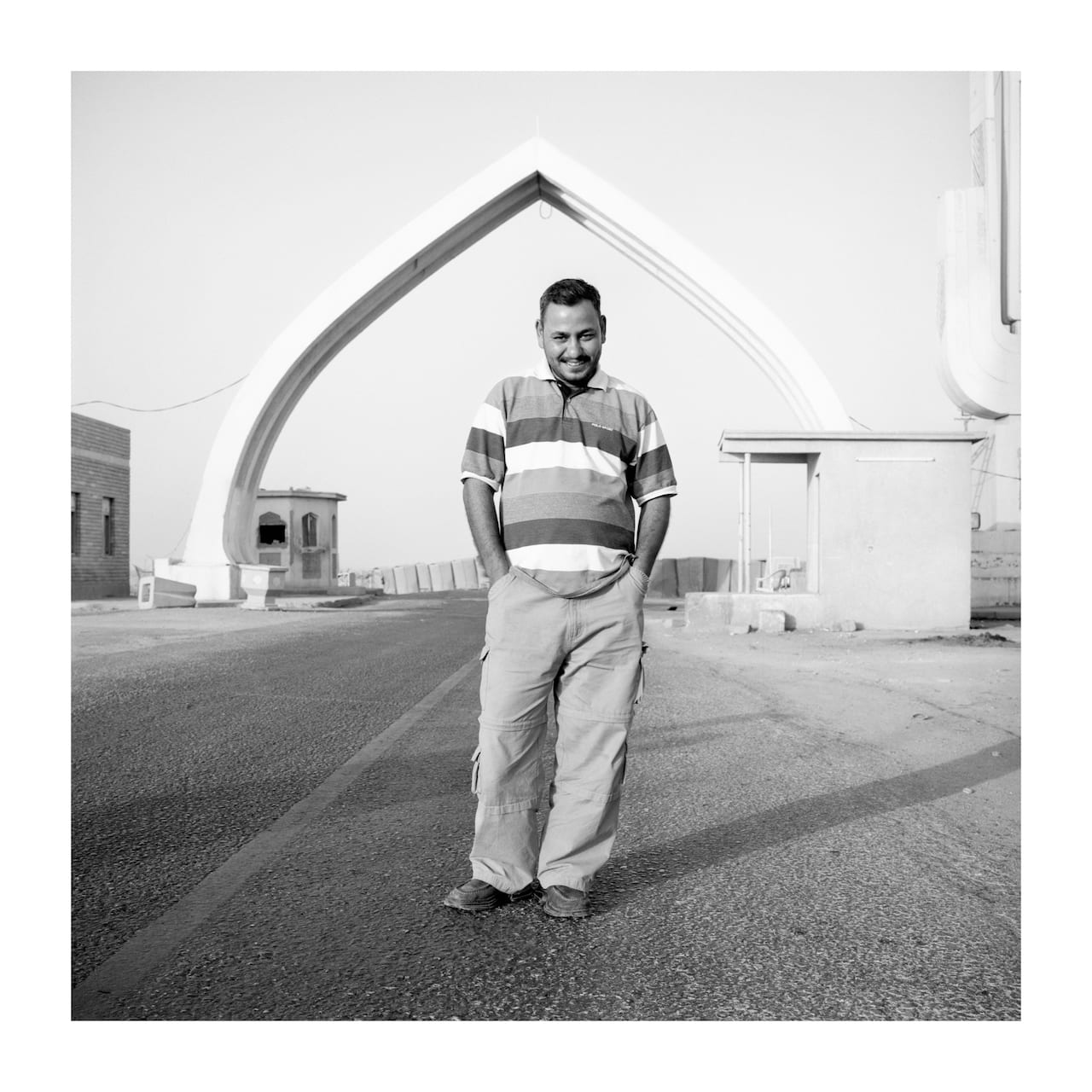

Hemmerle points to a photograph of a smiling man, hands buried in his pockets, standing under an arch in the village of Tarbil, Iraq. “He was my fixer. He was Shia and his family had a long history in Baghdad,” he says. “For whatever reason he was ferrying people like me to and from Amman. We hit it off on the first night with a long argument about the concept of god. We smoked about two packets of cigarettes between us and just argued and argued. It really bonded us.

“Anyway, he got chased out of Iraq because a group that was probably like the beginnings of ISIS threatened to kill his whole family. He’s in Finland now.”

When asked if any of the subjects in THEM know they’re in the book, Hemmerle points to a picture of Rafi, a 16-year-old boy who translated for him in Kabul. “He knows,” he says. “The book is dedicated in part to him. He’s Dr Rafi Hamidi now, he’s a heart surgeon in China but he goes back to Kabul a lot. Maybe one day instead of building a bronze statue of someone who killed a bunch of people they’ll raise one for Rafi, for all the lives he’s saved.”

When Hemmerle first returned from Afghanistan and Iraq, few were interested in these photographs, or the stories they told. The time wasn’t right, he supposes, or perhaps Americans have only just started to question the stories they were told back then. THEM intends to challenge those who read it, urging us to re-evaluate those stories but also, by implication, contemporary propaganda like them.

“The title is intended to invite argument,” he explains. “People ask me: ‘Who is the Them?’ I say, yeah, exactly. There is no them. It’s just us.”

THEM is published by Kehrer Verlag, priced €39.90 www.kehrerverlag.com/de/sean-hemmerle-them www.seanhemmerle.com