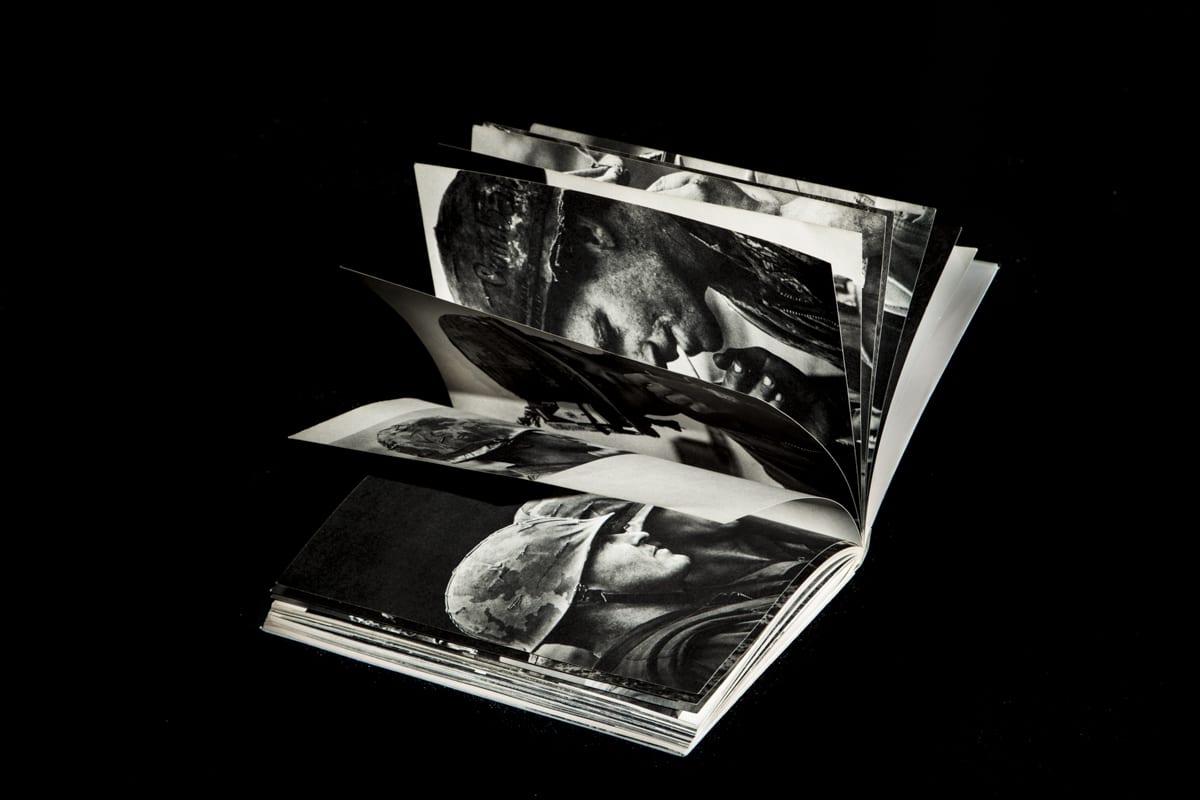

In 1968, the American photojournalist David Douglas Duncan returned from photographing the horrors of the Vietnam War. His images of the bloody siege of Khe Sanh had appeared in Life, but the photographer wanted to say more, and self-published a small paperback entitled I Protest. Featuring 122 stills from the battle, along with text openly criticising the conflict, Duncan printed 250,000 copies of the publication, which he sold for $1 each. Through releasing the work into society on his own terms, the photographer succeeded in inciting debate and dialogue about the conflict.

I Protest epitomises an approach to photography that Photography & Society, a new MA course at the Royal Academy of Art, The Hague (KABK), will explore. “We are trying to re-contextualise the meaning of photography within society and present it as a platform to connect with, and communicate to an audience, whoever that audience may be,” explains Donald Weber, one of the programme’s tutors. The teaching staff, all respected photographers in their own right, also comprises Lotte Sprengers, Rob Hornstra, Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin.

The school already has an intensive four-year photography BA programme, during which students are encouraged to develop their practice, defining a specific methodology and discovering and refining their own visual voice. “But what happens once you’ve created work?” asks Sprengers. “This is a question that we begin to address during the BA, but need more time to explore in greater depth. The MA should provide this.” The staff are unanimous in their desire to lead a programme that will examine the impact of photography in a social context and hope that this will result in students creating work that engages with its viewers, both physically and conceptually.

Understanding and taking responsibility for the impact that an image can have once it is released into the world is a central focus of the MA. “Having an impact doesn’t mean that you need to change the world,” says Hornstra. “But it is important that one is aware of the impact they are making and what that impact means.” Arguably one of the supreme modes of communication today, given its near universal accessibility, a photograph possesses the potential to incite discussion, debate, and even change. “It’s about understanding what happens when photographs are released into the wild, into society. How do they behave, how do they engage, how do they communicate?” adds Weber, “You as a maker need to take responsibility for your work in the context of the wider world.”

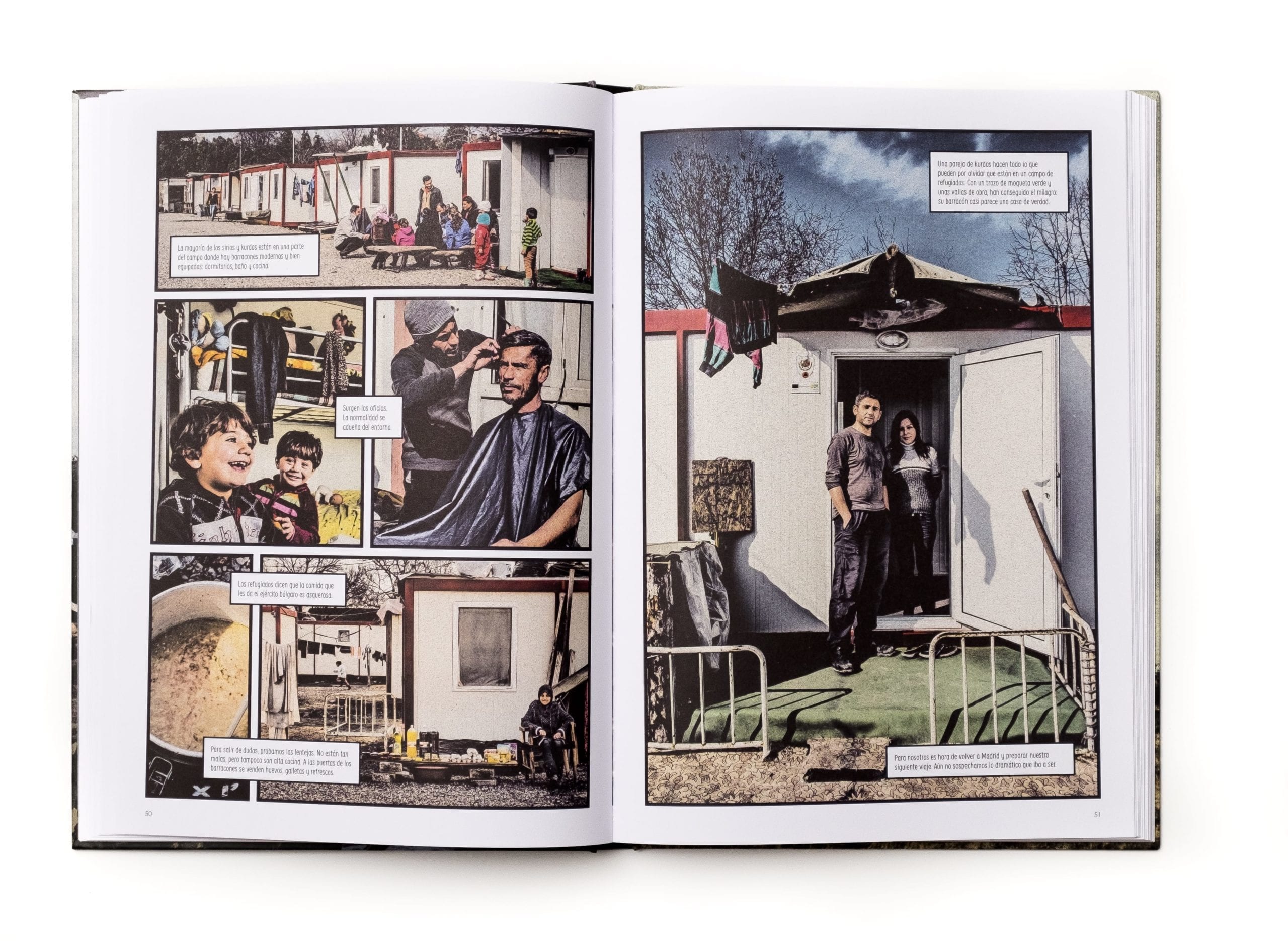

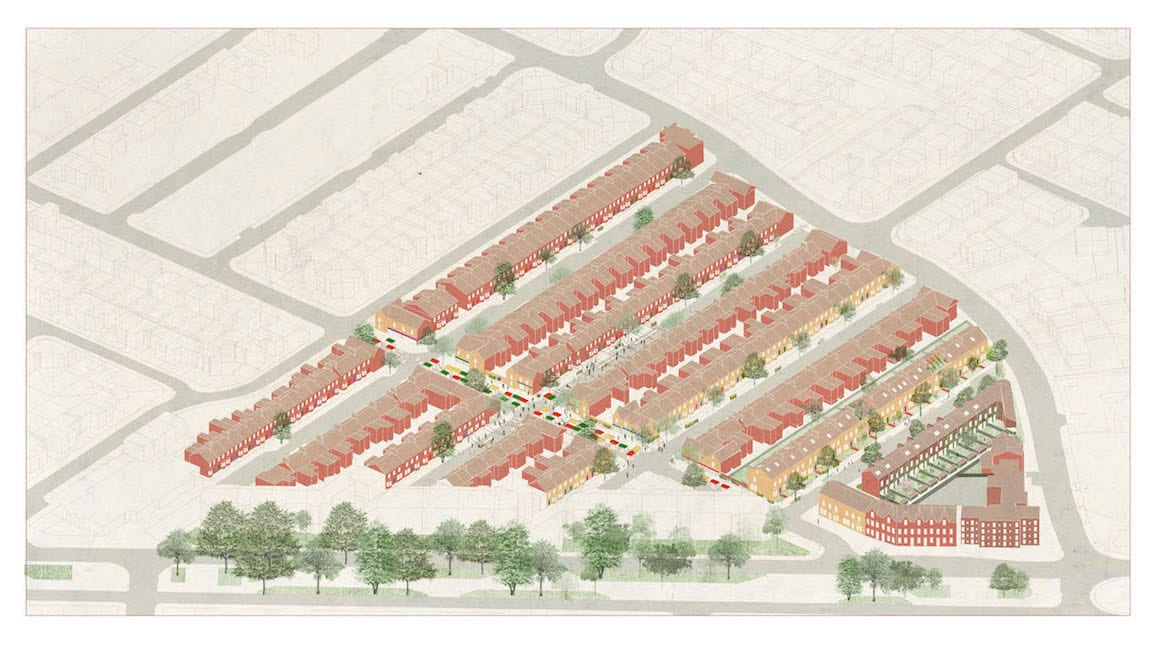

When I first meet Weber, Hornstra, Sprengers and Broomberg their dedication to the development of the MA is immediately clear. In creating the programme, the team looked to the work of a range of practitioners who, like David Douglas Duncan, in myriad ways have engaged with society through their practices. Carlos Spottorno was one. His project La Grieta (The Crack) was published in an unusual format. Existing somewhere between a photo book and graphic novel, La Grieta brought Spottorno’s three-year documentation of the European Union’s external borders to new audiences, resulting in the project having a far greater impact. In a different way, Assemble – a collective of young architects and winners of the Turner Prize 2015 – actively intervened in society with its project in Liverpool’s Granby Four Streets. By working with a local community in Toxteth, who had refused to abandon their houses, Assemble helped to revitalise the long-neglected neighbourhood.

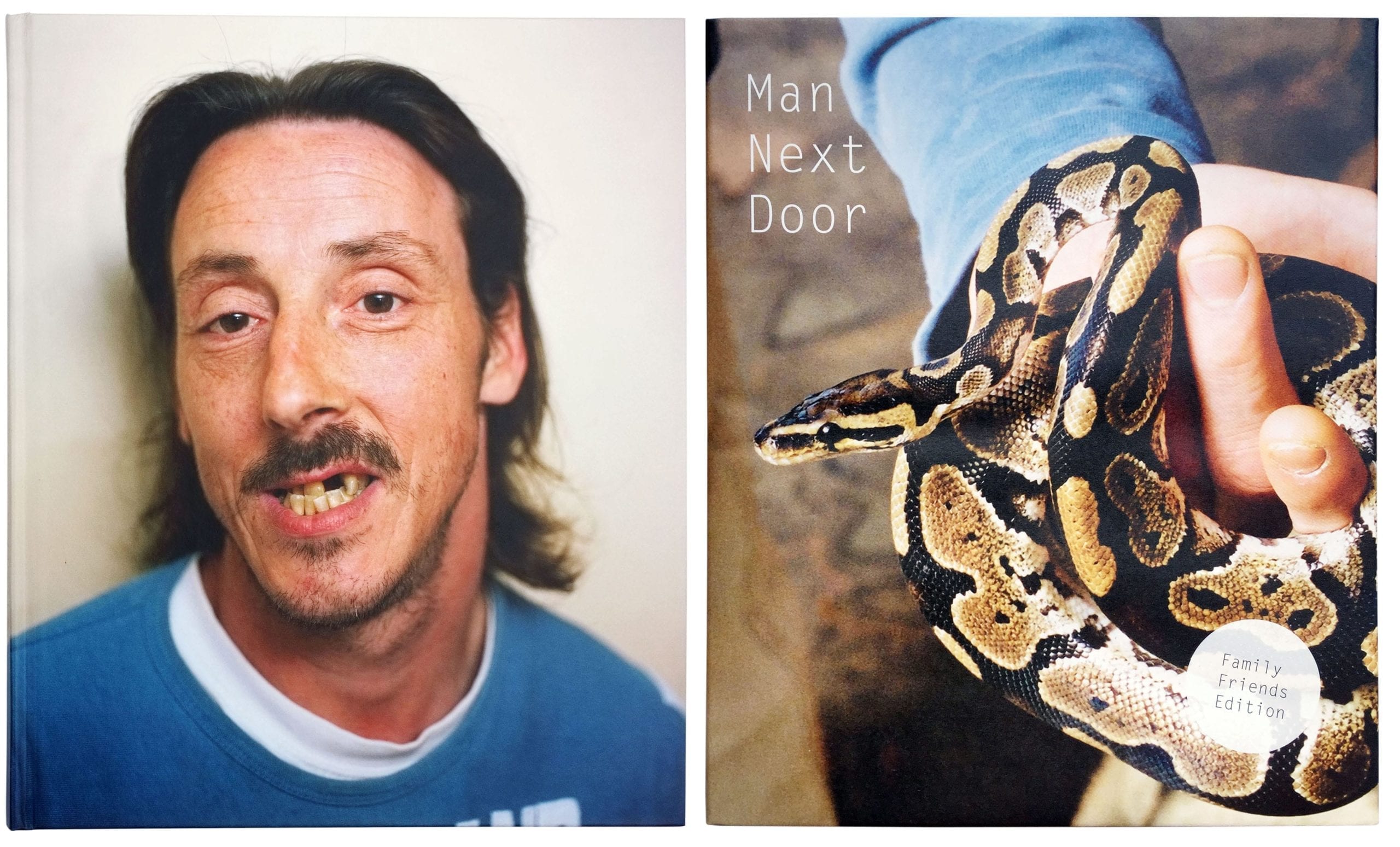

The MA’s professors also referenced their own work. The ultimate goal of Hornstra’s project Man Next Door was to create an encounter, and even a collaboration, between different groups in society who would normally have little comprehension for one another. In the end, this came to fruition, not through the photographs themselves, but at the opening night of the exhibition. “At the show’s private view, a large group of hardcore, working-class people from Utrecht – all relatives and friends of the project’s protagonist – visited the Centraal Museum in Utrecht for the first time,” says Hornstra. “They viewed the exhibition among the cultural elite, also in attendance, who hardly knew how to deal with the presence of this new audience.”

Meanwhile, Broomberg and Chanarin’s recent film installation The Bureaucracy of Angels addresses the current migration crisis, highlighting the ongoing legacy of this contemporary reality. Centred around the demolition of 100 migrant boats in Sicily, which arrived laden with refugees from North Africa, the film is narrated by the hydraulic jaws of the digger tasked with destroying the abandoned vessels. Commissioned by the public art programme Art on the Underground, and shown for almost two months at Kings Cross St. Pancras, the artists were able to bring the project to a much wider audience by displaying it in this public setting. “Engaging a public that’s not coming to a place to see an artwork, but is confronted by one, is an interesting problem to solve,” reflects Broomberg.

Although the programme’s ambitions and guiding principles are established, Photography & Society will continue to evolve alongside the interests of its students and professors. “When a course first begins it goes on a journey, just like a student does,” says Broomberg, who had just made his fortnightly commute from Berlin to teach for the day. “It’s not set in stone. We have the luxury here of being very honest and self-critical.” Indeed the school itself, the oldest art academy in the Netherlands, exudes an atmosphere of openness and experimentation, with the work of students spilling out of their studios into the hallways and communal spaces of the building.

“This will not be a hermetic course, functioning solely within the walls of an art school, and, by extension, the walls of the white cube,” stresses Broomberg. Instead, the two-year MA will place an emphasis on research and collaboration to ensure that the work created by students is engaged and informed. KABK was the first art institute to establish a formal collaboration with a university, partnering with nearby Leiden University in 2001. Students on the MA programme will have the opportunity to conduct research at Leiden, and, by extension, collaborate with the scholars they encounter. With programmes in design, fine arts, fashion, and architecture, KABK will also offer an array of opportunities for students to work with peers from over 40 countries and a diverse array of artistic disciplines.

These processes of collaboration and research will extend beyond the act of making work and out into the local, and global, community too. “Being situated in The Hague, you’re surrounded by international institutions on various scales, from civic organisations to human rights institutions,” says Weber. Currently, the academy has 60 official partners outside of the field of art and culture, including private companies, non-profit organisations, and government agencies, with which students are encouraged to collaborate in an effort to inform their work and widen both its reach and impact.

“Collaboration is about working with people who will enable you to create the work you want, but, also about becoming aware of issues that need representing,” says Weber. Engaging with the concerns of both organisations and individuals, and using photography as a conduit through which to bring these to the attention of society, will exist as a central part of the programme.

“Ultimately, we will be educating independent makers,” asserts Hornstra. “These makers will be at the centre of their self-produced projects; aware of how to collect the right people around them to fulfil these projects, and then how to bring their work back into society.” Photography & Society is currently open for applications for the first run of the two-year programme commencing September 2018, and is looking for practitioners keen to use their work to engage with the wider world, and provoke action, awareness and even change. In the words of Weber: “There are enough artists, what we need are people who are going to act as participants in society.”

–

Photography & Society is now open for applications. The deadline for enrolment is 1 May 2018.