On 24 July 2018, the shale gas firm Cuadrilla was given the go-ahead by the UK government to begin fracking at a well in Lancashire; the first onshore shale gas well to be fracked in the UK. Then, a few days later, a buried report by the UK government’s Air Quality Expert Group emerged detailing the negative impacts of fracking on air pollution. Fracking is no longer something that might happen in the UK; it is about to become a reality.

Fractured Stories, a British Journal of Photography commission supported by Ecotricity, gives one photographer the opportunity to explore the subject of fracking in the UK. After a lengthy judging process, Rhiannon Adam has been selected as the winner.

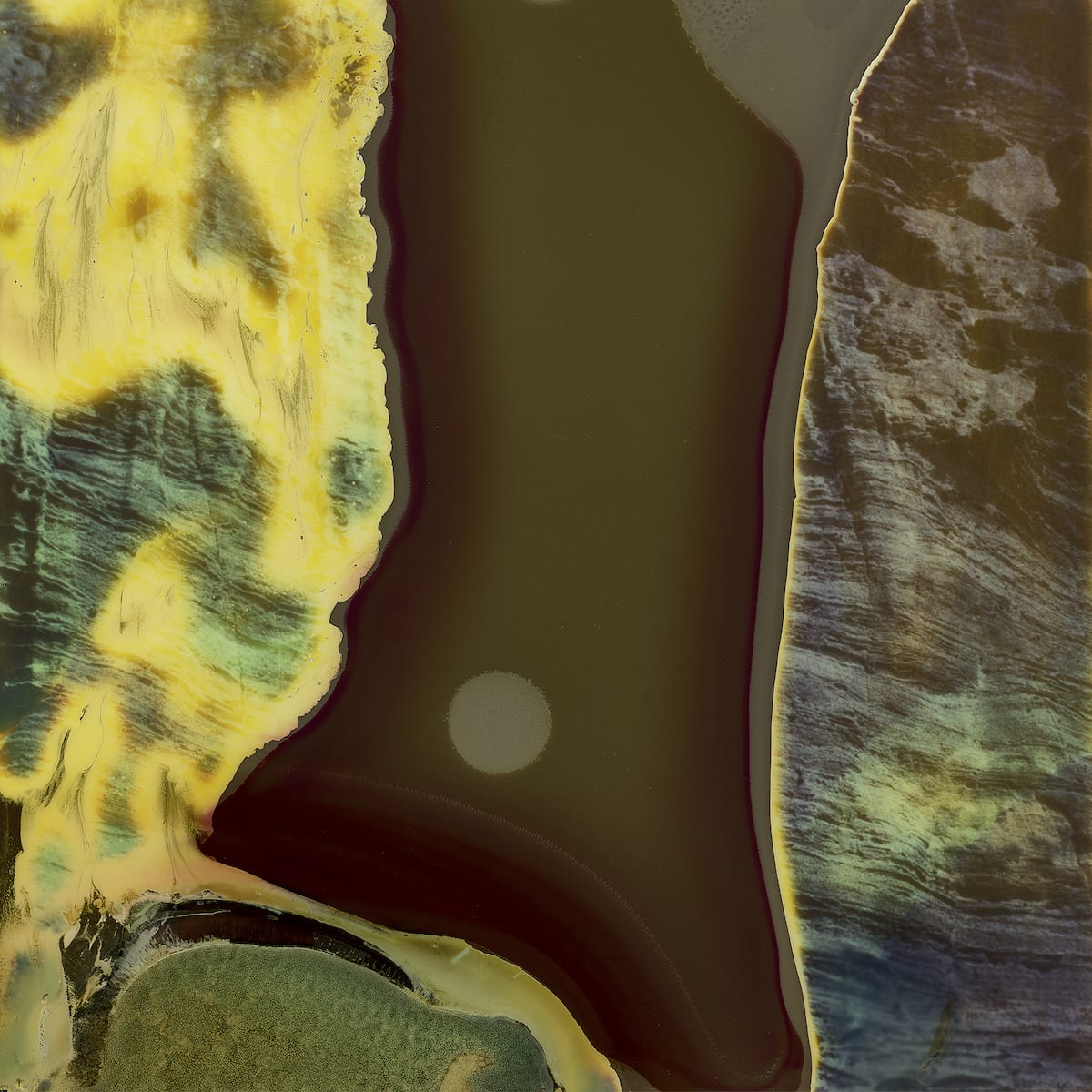

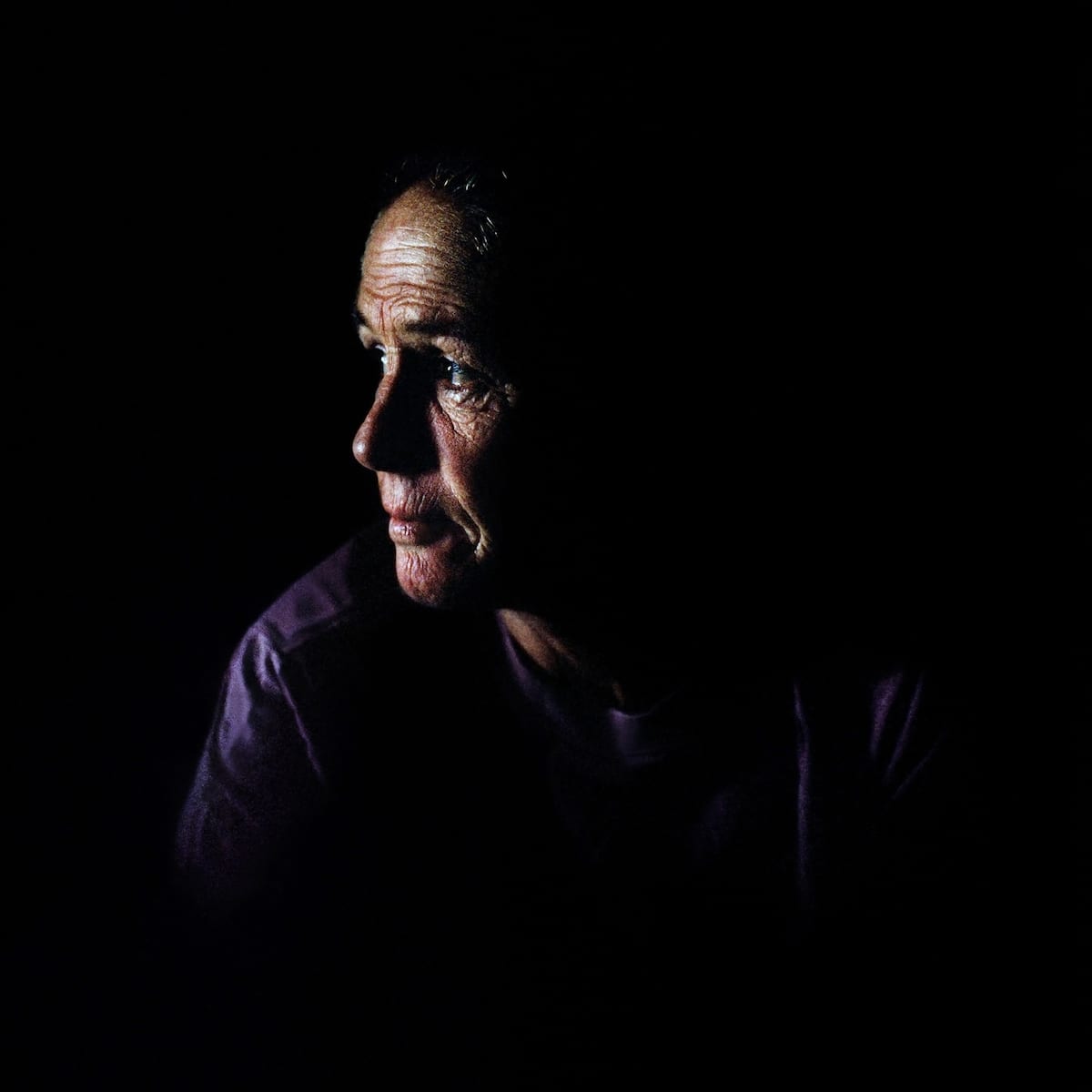

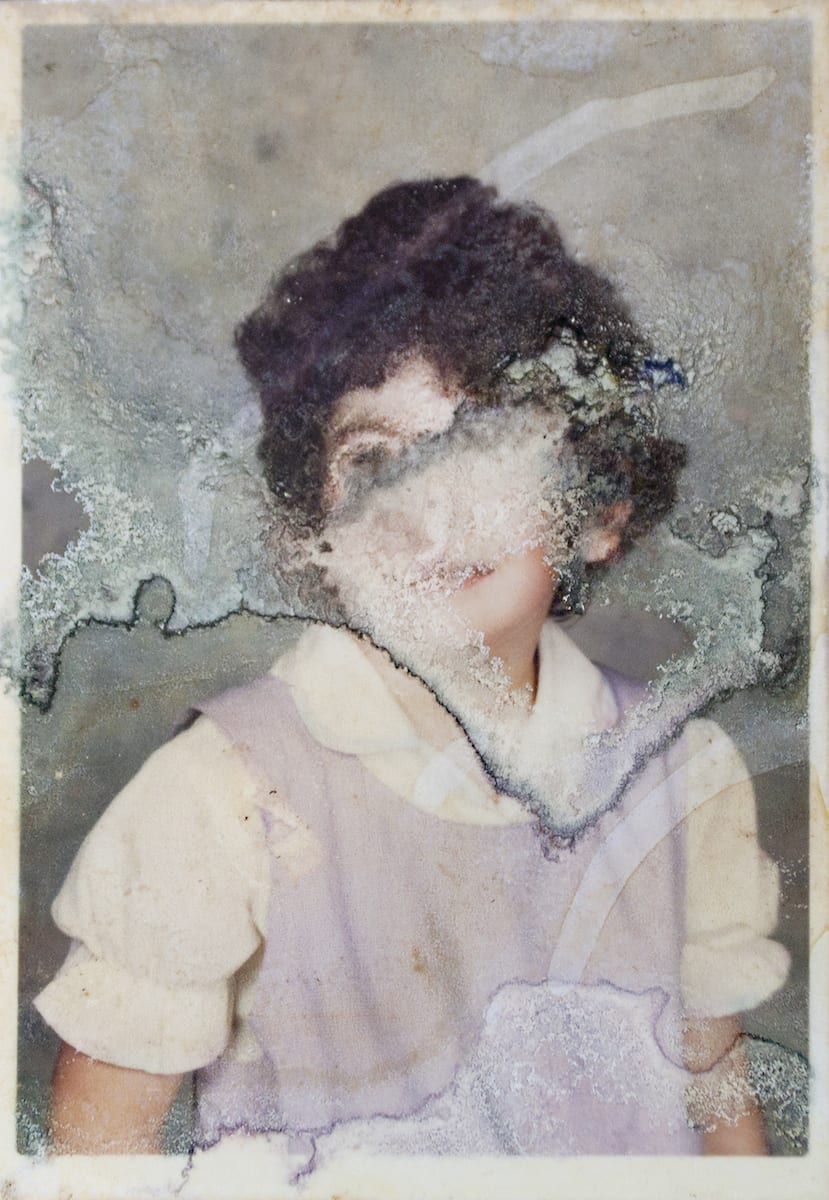

“I want my project to incite an emotive response to the subject: it will capture the human side of the story and unite it with the chemical,” she explains. Beginning with a documentary approach, Adam will immerse herself in the communities and landscapes caught up in the fracking debate, focusing on the Lancashire region. She will then employ an experimental approach to processing, using constituent chemicals from fracking fluid, to render the potential threats of the process visible.

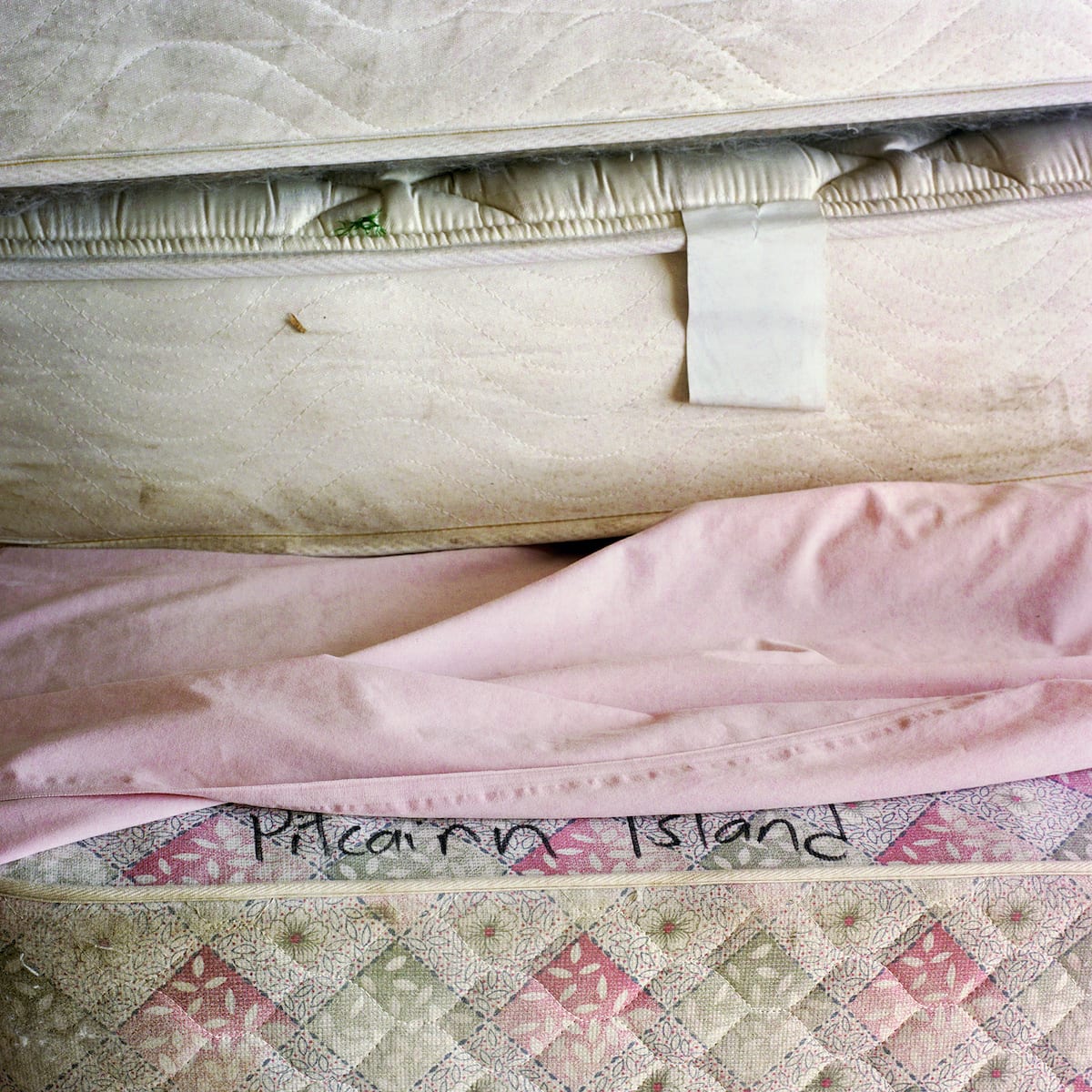

Rhiannon Adam is a London-based photographer whose practice straddles art photography and social documentary. Her long-term projects are heavily research-based and the resulting images are captured almost exclusively in ambient light through the hazy abstraction of degrading instant-film materials and colour negative film.

In 2015, she travelled to the remote island community of Pitcairn in the South Pacific, which, a decade earlier, entered into public consciousness after a string of high profile sexual abuse trials. Adam succeeded at infiltrating the closed community and created the first in-depth photographic series on the island, entitled Big Fence / Pitcairn Island.

Over a six week project period, commencing this week, Adam will work on creating her new body of work. The resulting project will be published on BJP-Online throughout November and December 2018.

Below, Adam shares how she plans to approach the commission and why it is an important time to be addressing this issue.

–

How do you plan to approach the commission?

My primary focus will be on capturing the fears associated with fracking. I want to represent the unseen effects that the process may inflict on the environment, focusing, in particular, on the risks associated with the fracturing fluid that is used to extract shale gas and oil.

Much of the environmental objection to fracking centres on the toxic chemicals that are pumped into shale rock, and the long-lasting and largely unquantifiable impact that these may have on the environment, particularly in regard to polluting water supplies and causing seismic disruption. It is too early to know the precise effects – only time will tell – so I am essentially photographing the unknown.

My aim is to represent these perceived dangers in an engaging way through employing a disrupted aesthetic. I use analogue film in most of my work and clean water is a key component in processing this. But, what if this clean water was suddenly to become contaminated – what would this look like? How would this change the appearance of the image? By manipulating the film itself, I will allude to the wider context of fracking without reducing it to clinical imagery. My approach will be experimental because it needs to be; I cannot rely on the obvious.

Why have you approached the commission in this way?

My work is almost always process based. I am fascinated by the interaction between the composition of a photograph and the chemistry involved in its creation. I am also intrigued by the way that an image can be altered through interrupting, and deviating from, the correct treatment of it.

There are a number of high-quality documentary projects on the subject, particularly those which are based in the US, but, maybe through creating something jarring and discordant, the work will help provoke a more visceral and emotive response. I want viewers to pause and wonder why the photographs look the way that they do and, in doing so, engage with the issue in more depth.

Furthermore, because the commission period is relatively short, I won’t be revisiting the project year after year to observe gradual changes. Consequently, I need to do something that communicates the narrative immediately. By employing an artistic response to the topic, which straddles documentary and art photography, I will hopefully make an abstract and invisible process seemingly tangible.

What will the final body of work contribute to debates about fracking in the UK and further afield?

The work will provide a fresh perspective on the subject.

People who live far away from the existing and proposed fracking sites often experience a disconnect with what is happening. By creating something unexpected, and hopefully beautiful, I aim to shine a light on the concerns of locals and encourage a wider engagement with the issue.

Maybe, if we tell the story differently, we can instil viewers with a sense of urgency, or, at the very least, a curiosity about the subject of fracking.

Ultimately, the more voices that can be involved in the discussion, the better it will be for everyone in the long run. Even if the process became so widespread that it would seem the anti-fracking battle had been lost, with fracking going ahead across the country, ongoing engagement with the issue will remain critical – it is our job to hold corporations to account and to provide an educated and informed resistance. Criticism is essential – without it, regulation stumbles and the future becomes even more uncertain.

Why is it an important time to be making work that addresses fracking?

We should be moving away from a reliance on fossil fuels, instead of investing in a process that will potentially cause more environmental damage. Right now I am sitting in London during one of the hottest summers on record: if there has ever been a time when climate change seems more apparent, it is now.

It is important to draw attention to a subject before it’s too late and the damage has been done. It is also important to engage with an issue in its early stages (though I know of course that the anti-fracking movement has been working tirelessly for years), even though it’s often harder to do so because it can seem like shouting into an abyss. No one, from either side of the fracking fight, can say for certain what the impacts will be. Even the fracking companies themselves don’t know what happens to the huge quantity of wastewater that they cannot recover from deep underground.

But, to me, fracking seems like a quick and dirty solution to the energy crisis when really we should be thinking more long-term. If even a small percentage of the damage that activists predict takes place, we will face serious and irreversible problems related to health and the environment, which will have an impact stretching far into the future.

This is not a fight without consequence; it is a fight for the future.

–

Fractured Stories is a British Journal of Photography commission made possible with the generous support of Ecotricity. Please click here for more information on sponsored content funding at British Journal of Photography.