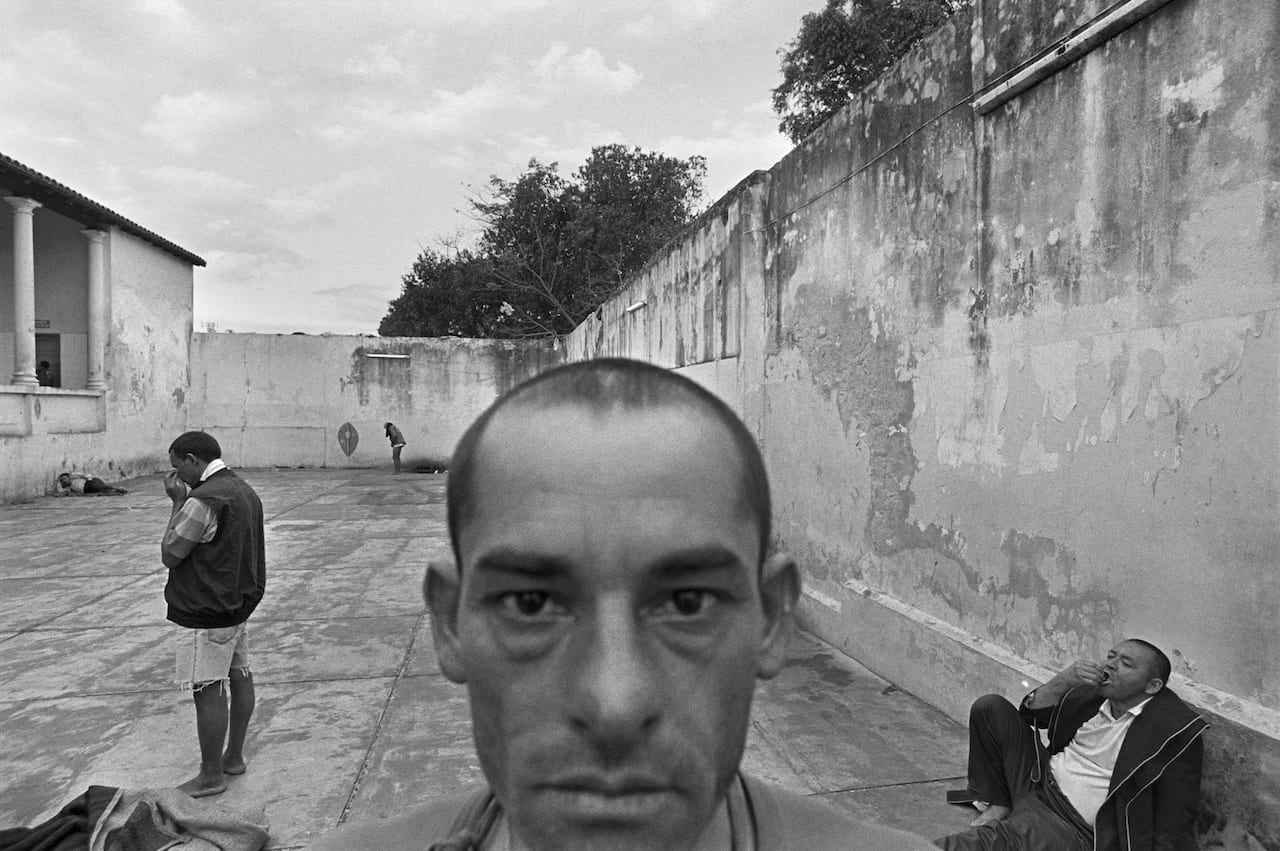

“You’re always looking for that time where everybody forgets you’re there and becomes themselves. Surprisingly they do, sometimes to the detriment of what you knew about them,” says Eugene Richards, who has devoted his career to documenting social injustice in America, and to injecting himself into intensely personal situations.

Richards’ style is up-close and unflinching, “ironically it’s the process of becoming as not there as you possibly can, if you hang around long enough people don’t care”. Though his photography has been described as poetic and lyrical, he has never thought of himself as an artist. “I went in with some knowledge of photography, but mostly with the idea of providing information,” he says.

After studying under Minor White at MIT, Richards joined VISTA, a government program formed as part of America’s “war on poverty”. He was sent to work in Arkansas, a southern US state, where he helped found Many Voices – a community newspaper, which reported on black political action and the Ku Klux Klan. The photographs he made during these four years were published in 1973 in his first book, Few Comforts or Surprises: The Arkansas Delta.

Returning to Dorchester, Massachusetts, Richards began to document the fast-changing, racially-diverse neighbourhood where he had grown up. In 1978, he published Dorchester Days, and that same year, to his surprise, he was invited to join Magnum.

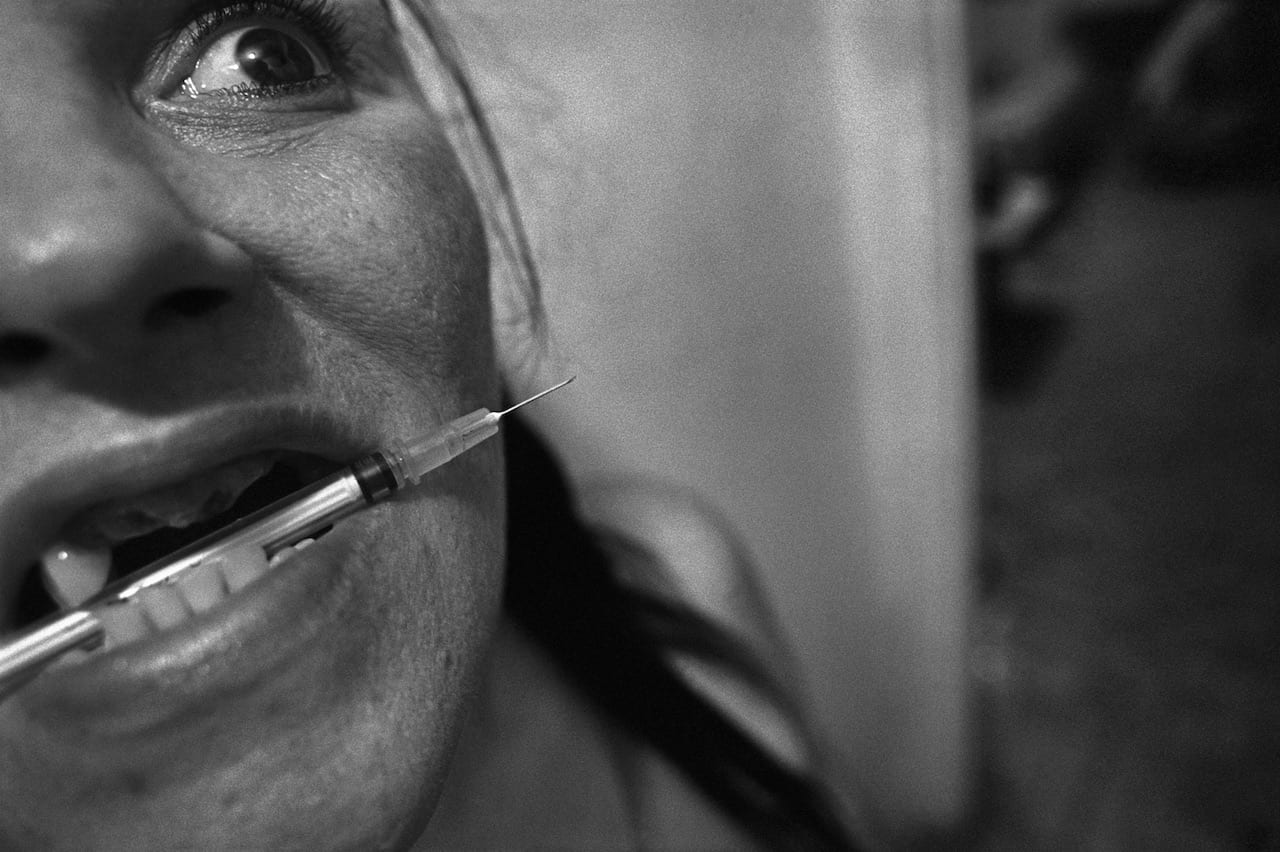

His work has won acclaim from various institutions, including the ICP Infinity Award for Below The Line: Living Poor in America, and an Award of Excellence from the American College of Emergency Physicians for The Knife & Gun Club: Scenes from an Emergency Room. His book on the effects of hardcore drug-use, Cocaine True Cocaine Blue, received the Kraszna-Krausz Award for Photographic Innovation in Books. Other significant projects include a close look into the lives of those hidden away in public asylums, portraits of people deeply affected by the terrors of war, and a series in remembrance of the events of 9/11.

Perhaps surprisingly, though he finds it crucial to establishing a connection with his subjects, Richards prefers to approach the projects “cold turkey”, finding that “research predispositions a story”. Over the years, he has learned to adjust himself to fit into different situations, and he says he tries hard not to be judgemental. Maybe, he says, “my only gift in life is being a bit boring, because people don’t pay a whole lot of attention to me after a while”.

But while getting access and sparking relationships can be tough, what’s even tougher is leaving the situation. “You do get involved, despite what people say at times,” he says. “I’ve been in scenes where men have been abusive to women and you really do have to intercede.” He’s never paid his subjects, but he has been criticised for interfering – for filling up a refrigerator after a shoot, or giving young addicts clean syringes because they were giving each other AIDS.

“I think the worst thing for a lot of [photographers], or certainly myself, is the fact that you always know, no matter what you see, that you can always leave,” he says. “If you’re around people that are hungry, they’re gonna still be hungry when you’re going home. That’s the toughest part. It’s not a good feeling to feel, it’s a pretty selfish feeling.”

Out of all his projects, Exploding into Life is perhaps his most emotional, and certainly his most personal. It documents his first wife, the writer Dorothea Lynch, and her battle with breast cancer, which eventually led to her death in 1983. Richards initially refused to photograph her, but “she was insistent”. “It was hard because you can’t have the camera up at intimate times. Dorothea would comfort me sometimes, more than I could comfort her, and there’s no camera there. I’m not in any the pictures, which is a mistake,” he says.

His favourite photograph from the book is of Lynch laughing, with her surgical scar in shot. It was taken as a young male doctor came in for a “psyche-quiz”, and asked her whether losing a breast made her feel like less of a woman. “I didn’t take it very well, I took him outside and told him he was an asshole,” says Richards. “Male stupidity is not uncommon, as you know.”

But Lynch continued to laugh, answering that “naturally, losing a breast makes you feel like more of a woman”. She was, he says, “extraordinarily forthright”.

Richards’ work has won him international fame, and he’s now staged many high-profile exhibitions – including the large retrospective now on show in New York’s prestigious International Center of Photography. Even so, he still finds it hard to see his work on display. “It’s always disconcerting to put the life of people you know on the wall,” he says. “It’s more like a family album than an exhibition. It’s a memory bank.”

Eugene Richards: The Run-on of Time is on show until 06 January 2019 at the International Center of Photography [ICP], 250 Bowery, New York www.icp.org/exhibitions/eugene-richards-the-run-on-of-time