“What do I know about it? All I know is what’s on the internet.” So said Donald Trump in an interview in March 2016, after he was confronted about the legitimacy of a video he had tweeted, along with the claim that the protester it depicted was a member of ISIS. The video has since been proved as a hoax, neatly demonstrating the difficultly of navigating between truth and fiction in today’s digital landscape. In a world where even a layperson can manipulate images on their phone, and spread them to thousands of fake followers with one click, how can we begin to know what is #real?

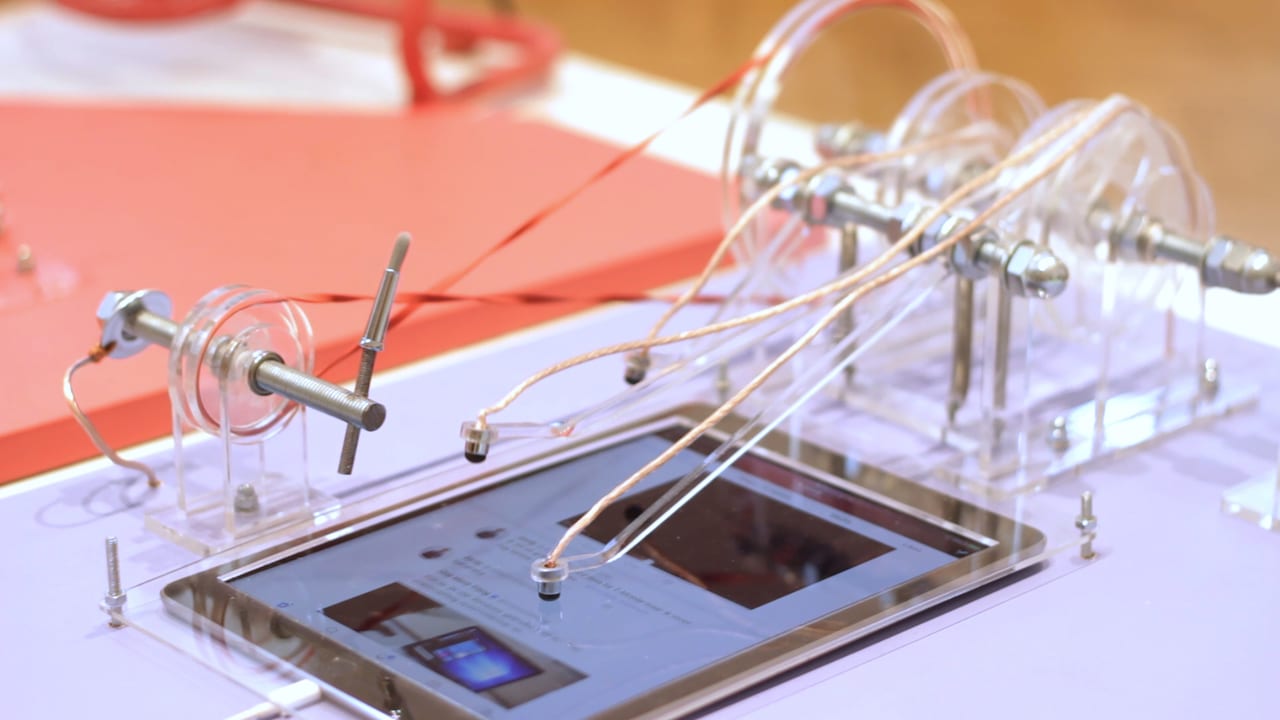

It’s the kind of question posed in All I Know Is What’s On The Internet, a new exhibition opening at The Photographers’ Gallery, London which includes work by 11 artists and collectives. It includes “social media machines” made by Australian designers Stephanie Kneissl & Maximilian Lackner, built to maximise activity and likes, for example; it also features wall-mounted installations by Eva and Franco Mattes that reveal the lesser-known, surprisingly personal, world of online content moderators. Curated to draw attention to the neglected corners of digital image production, the show helps visualise the vast infrastructure of online platforms, and the enormous amount of human labour needed to keep it churning.

Since TPG established its digital programme in 2012, the gallery has been investigating the impact of digital media photography via its virtual exhibition space, the Media Wall; an online blog, Unthinking Photography; and a bi-annual event dedicated to photography’s increasingly automated life. Past programming includes a show on video game photography, an installation on Japanese virtual pop idol, Hatsune Miku, and discussions on the politics and aesthetics of Microsoft Powerpoint.

This season the gallery wanted to think about digital photography in a different way, explains Katrina Sluis, senior digital curator at TPG. “The show is not about individual photographs and what they can do, but more about the kinds of systems and infrastructures through which they circulate or don’t circulate,” she says.

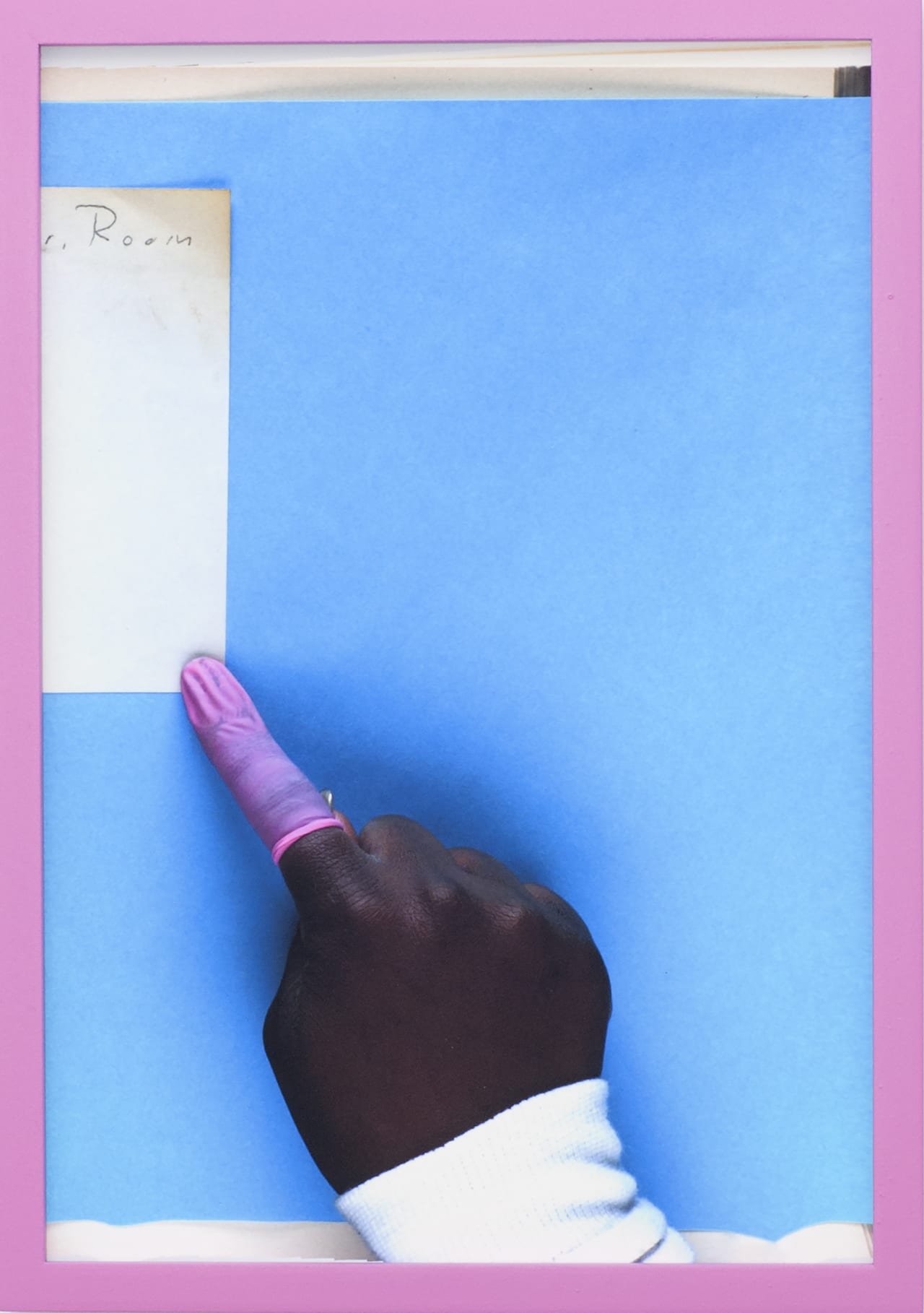

One strand concerns our own complicity in circulating images online, not just in terms of liking or retweeting but also in improving the intelligence of the machines that use them. For the last seven years, Silvio Lorusso and Sebastian Schmieg have screenshotted every image they were made to identify on the internet, for example – the details they were made to pick out to prove that they were human. What was once a warped set of numbers and letters incomprehensible to a computer has morphed into a more complex system, in which users are made to differentiate cars from street signs or shop fronts. Effectively, we are training the internet and machine vision, says Sluis, “we have become workers in the photographic system”.

Other artists involved include Andrew Norman Wilson, who presents screenshots from Google Books in which Google’s army of militant scanners have accidentally left a trace of their presence. And a photography project by IOCOSE shows how crowdsourcing platforms can be used to generate conspiracy theories online.

From January, an performative installation that will take up the whole third floor of the gallery is due to open – Operation Earnest Voice by Jonas Lund, a four-day experiment dedicated to reversing Brexit through social media. The artist will transform the gallery into an office space for internet trolls, who will be given thousands of fake twitter followers to try to manipulate social media channels. The public will be able to walk around, contribute to the task, and even attend board meetings.

“The whole point isn’t actually to reverse Brexit, but to open up conversations about the use of fake followers, content farms, and the way images on social media mobilise,” Sluis points out. The plan is to launch the installation with a “Silicon Valley-style” office party, and host events and discussions in the office while the troll farm are at lunch.

Exhibited at the same time as All I Know Is What’s On The Internet is the first UK retrospective of Roman Vishniac, a photographer who dedicated himself to scientific research. “Vishniac comes from a time where photography was able to tell us something about the world, and each other,” says Sluis. “It fits into an interesting dialogue with this show – if you think about photography today, can we know anything about each other?”

This conversation continued on 12 February, in a panel discussion titled The Instabot Industrial Complex which will examine the recent phenomenon of computer-generated instagram models like Lil Mcquela, the economy of buying fake followers, and the phenomenon of influencers. Constant Dullaart, a conceptual artist known for purchasing and re-distributing 2.5m fake Instagram followers for $5000 in 2016, will be among those speaking.

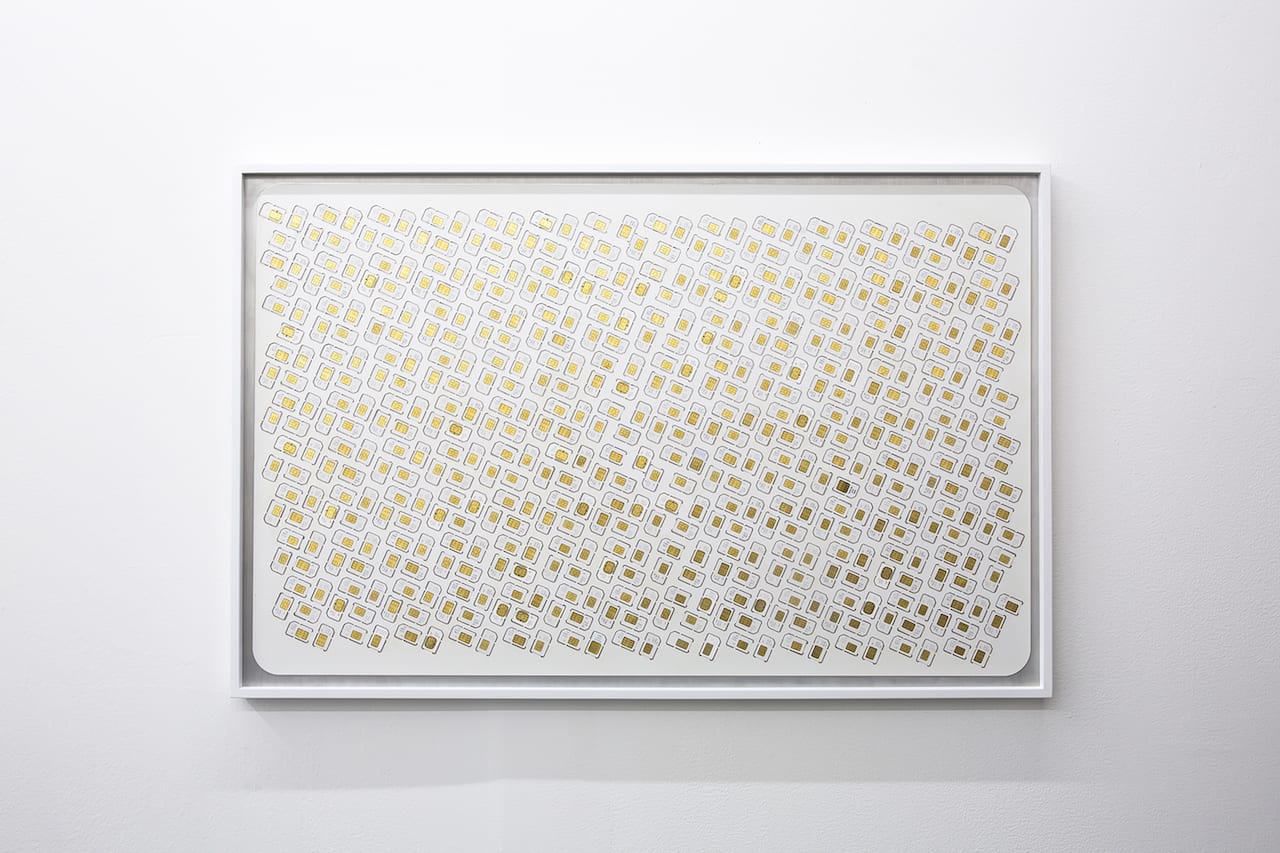

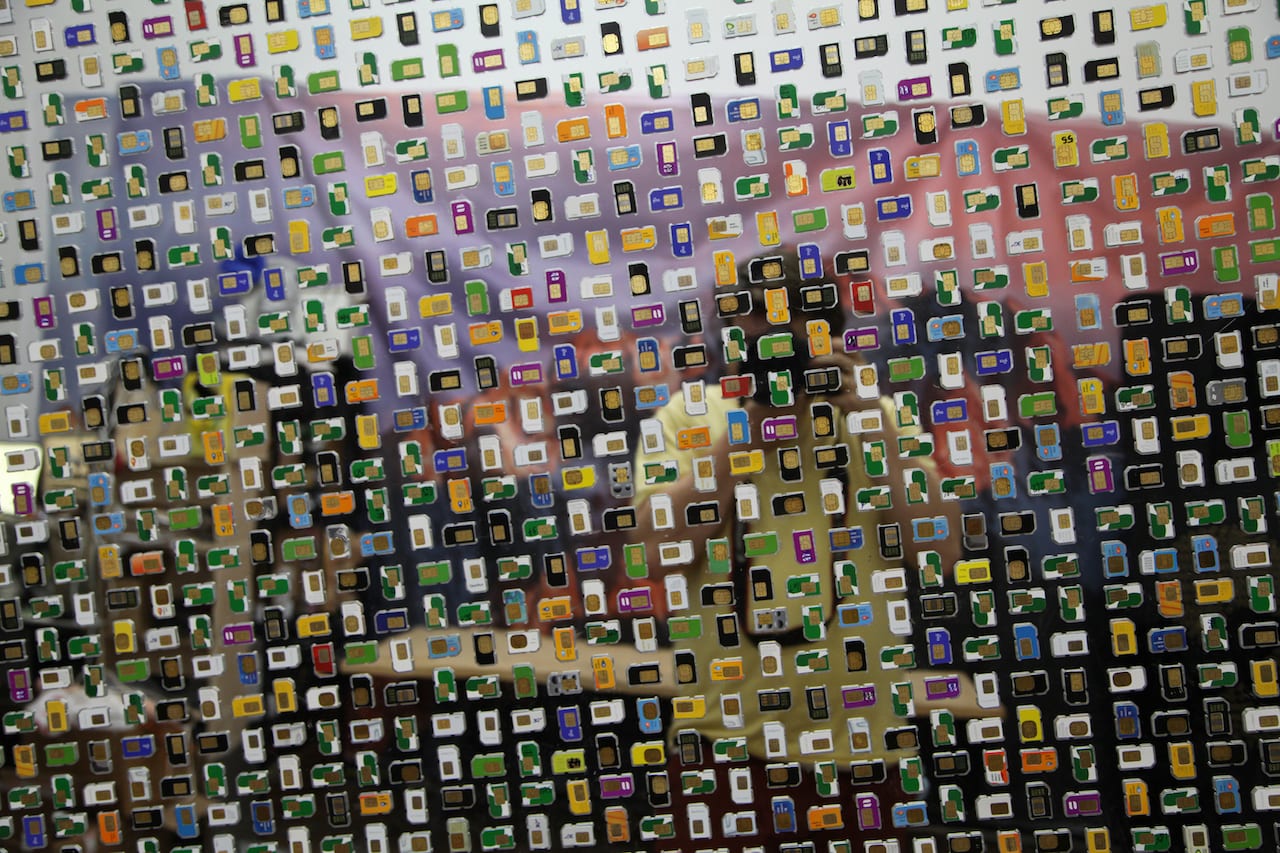

Dullaart is also exhibiting work in All I Know Is What’s On The Internet, looking at the most valuable fake followers on Instagram – those with phone-verified accounts, able to open multiple profiles under one identity. Dullaart will exhibit large mirrored panels presenting the hundreds of sim cards he used to create his own fake profiles and for visitors fond of a mirror selfie, this will probably be the most Instagrammable piece in the show. But rather terrifyingly, according to Sluis, if you share it on your profile, you may encounter a surprise visit from Dullaart’s Instagram army.

All I Know Is What’s On The Internet is on show at The Photographers Gallery, London from 26 October – 24 Febuary thephotographersgallery.org.uk