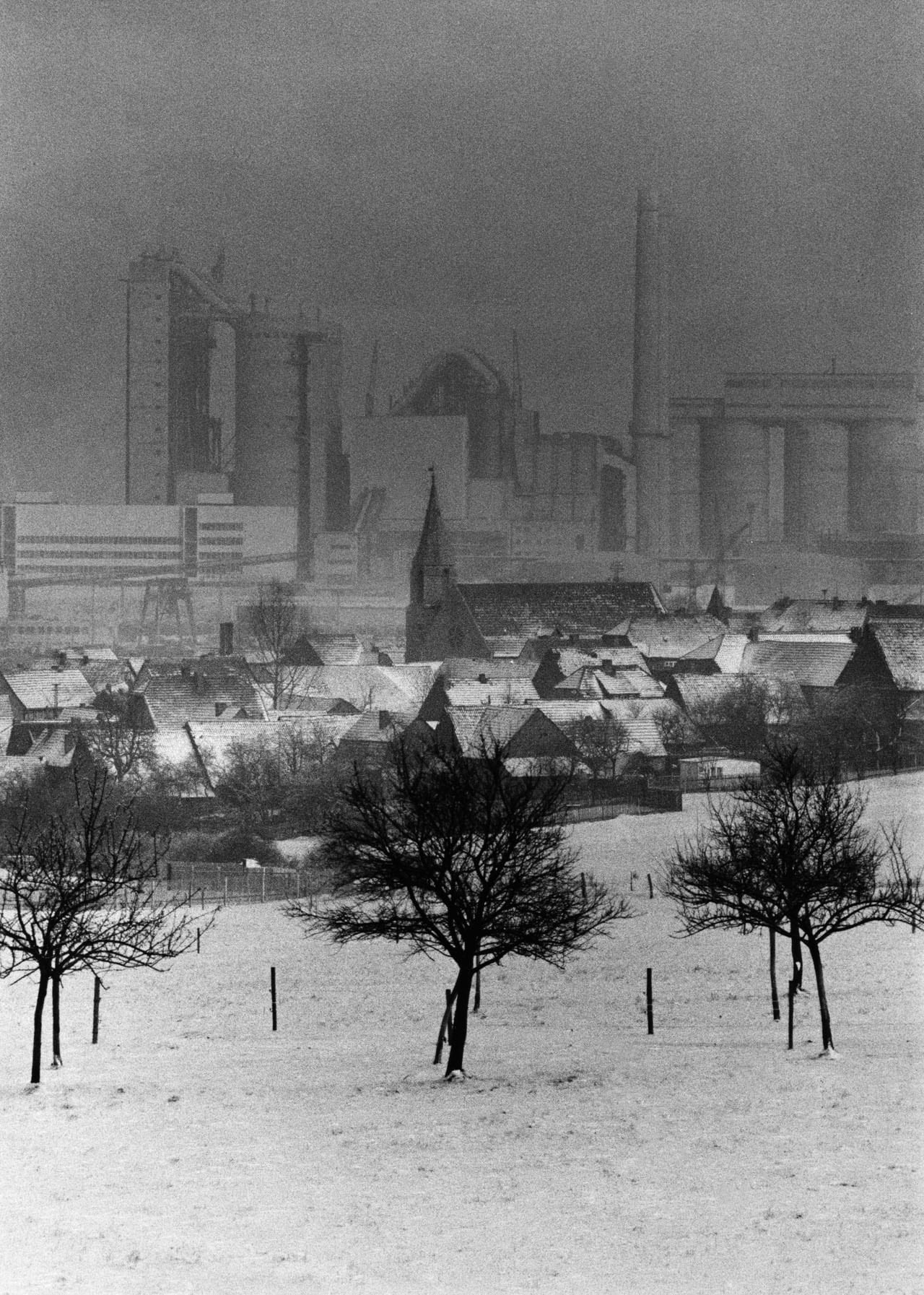

“This book….does not – and this I must emphasise – document life in the GDR [German Democratic Republic]. Rather, it shows how I saw this country and the people who lived here,” writes Roger Melis in the introduction to his book In a Silent Country, now published for the first time in an English edition.

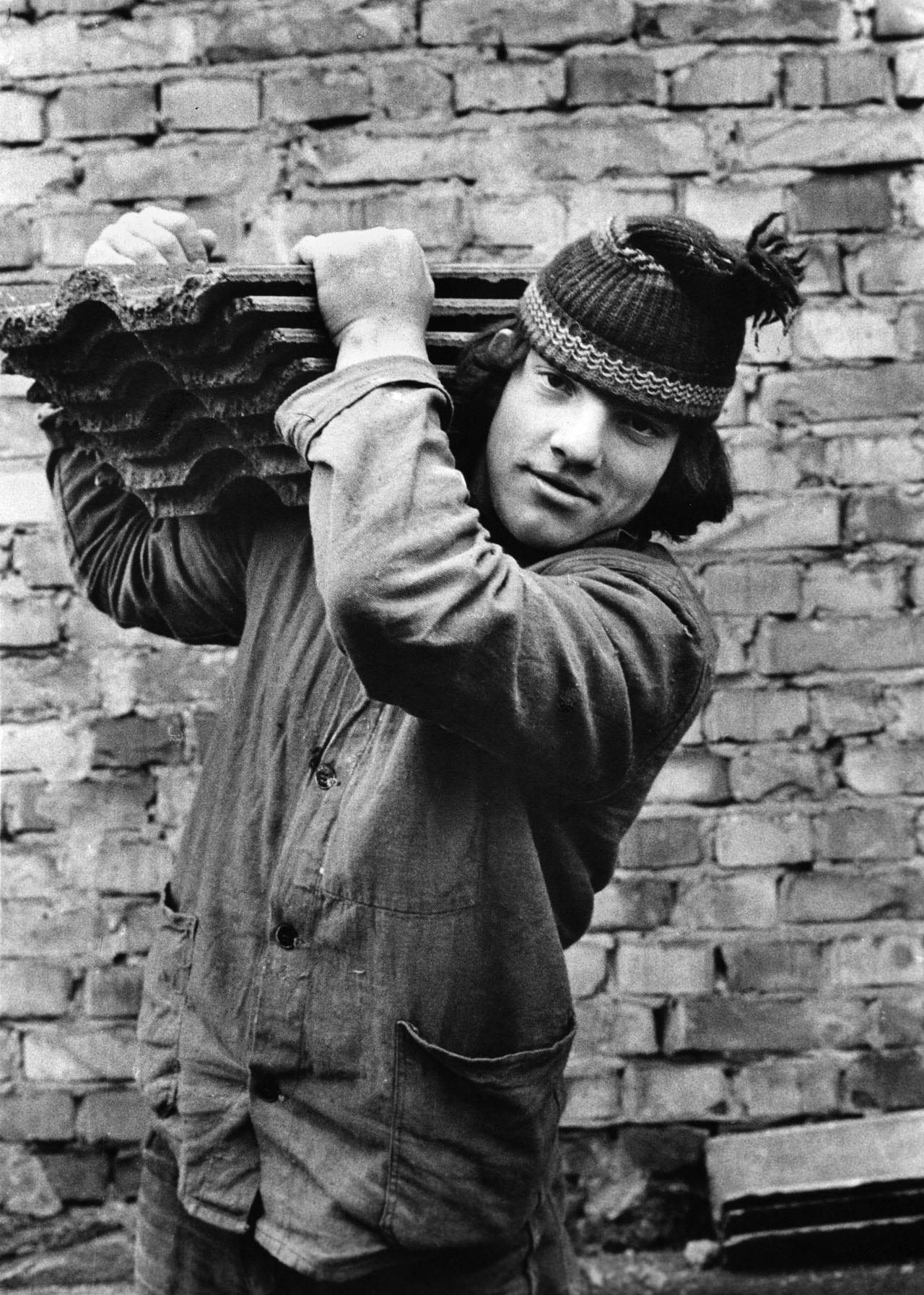

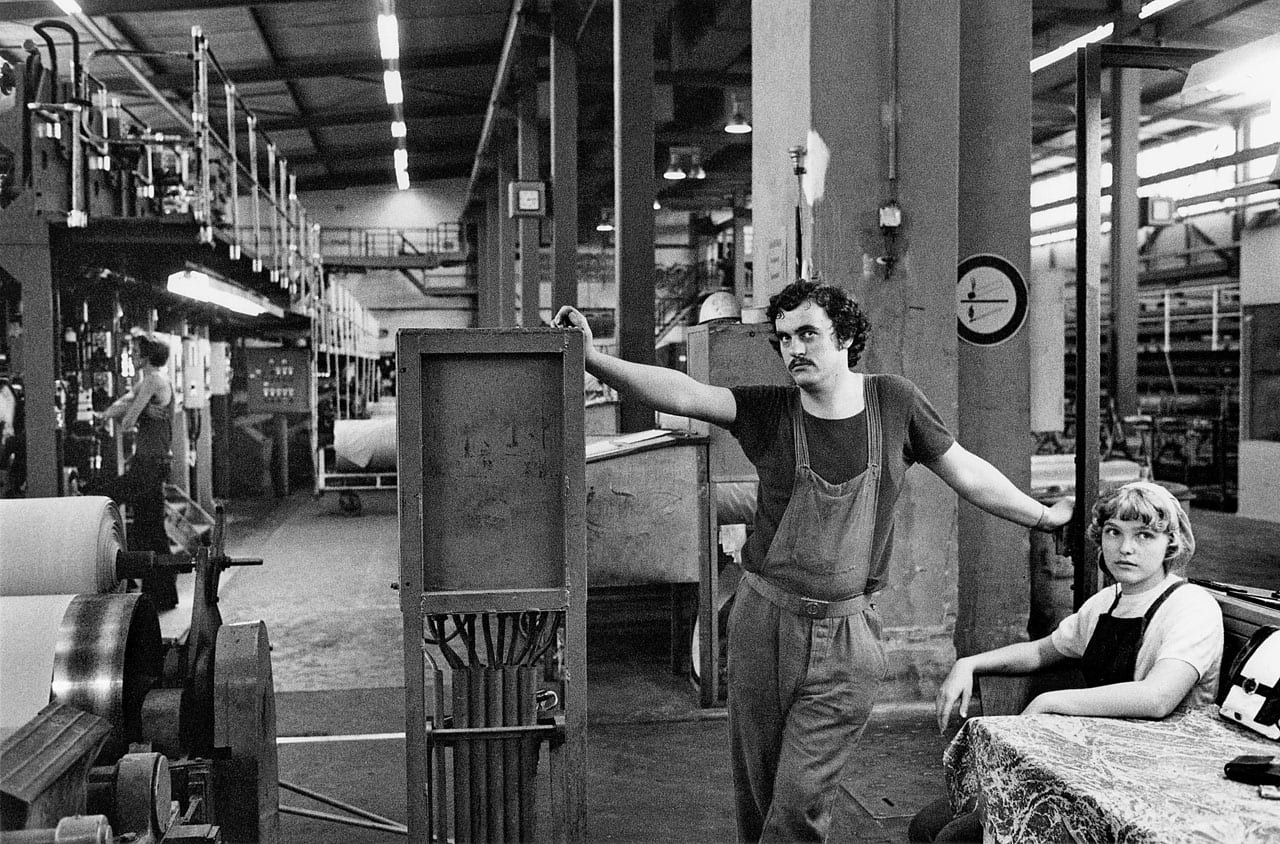

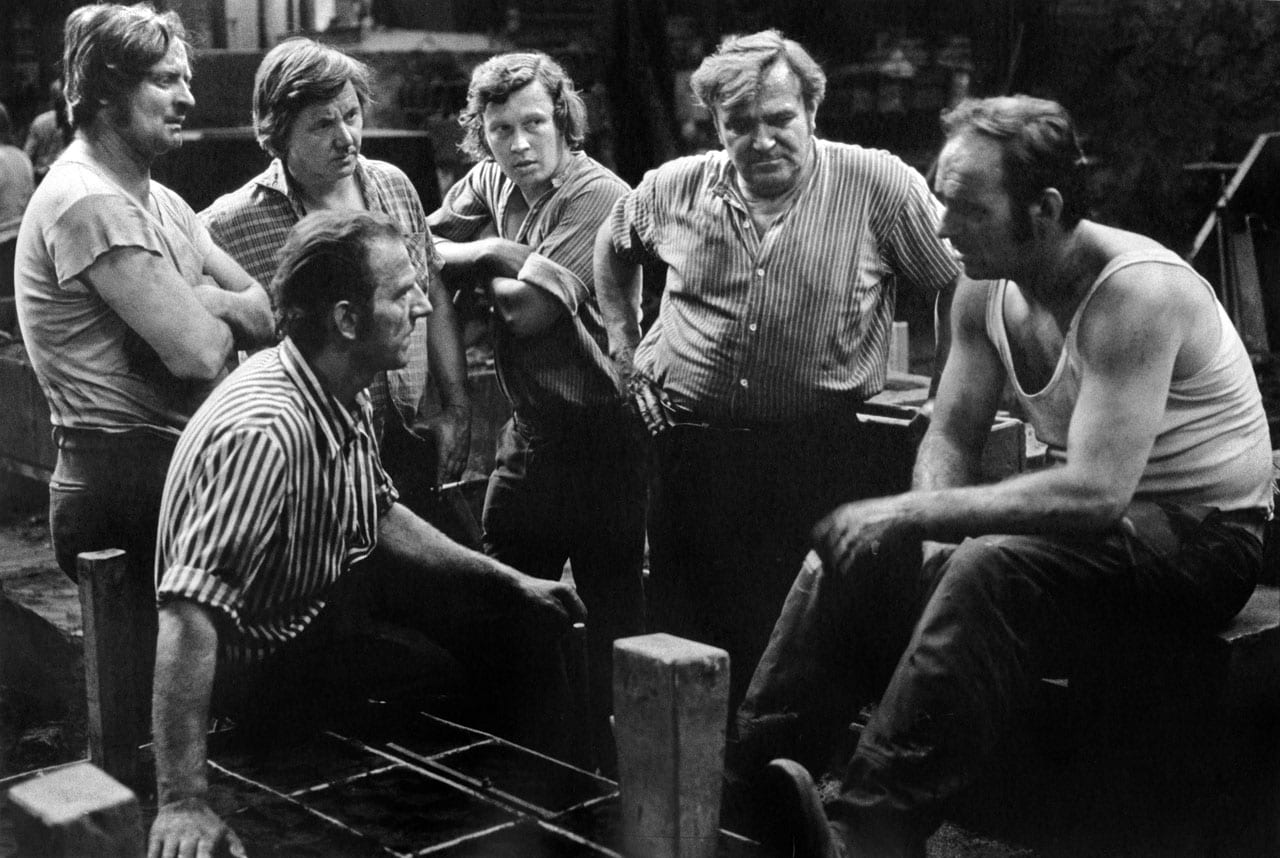

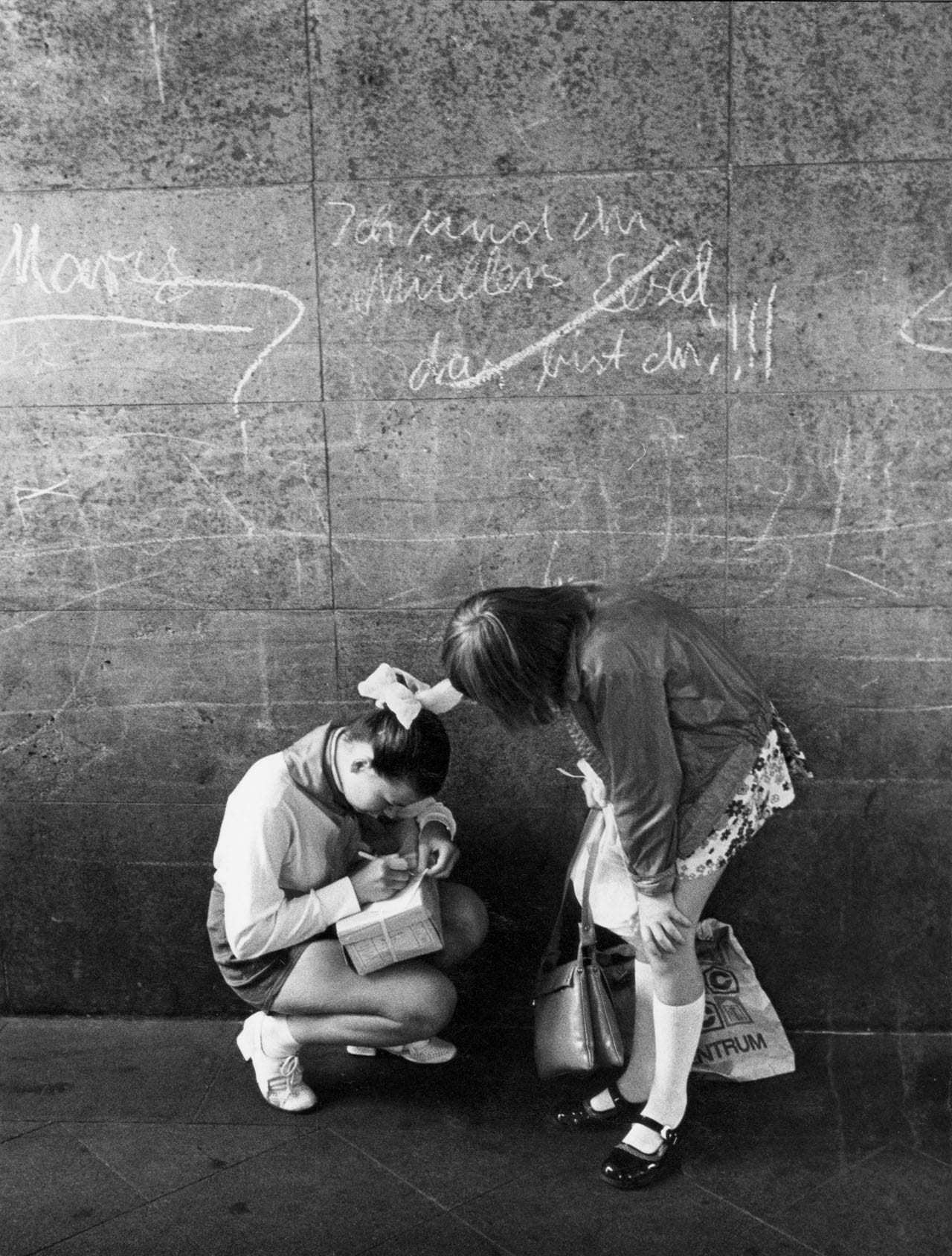

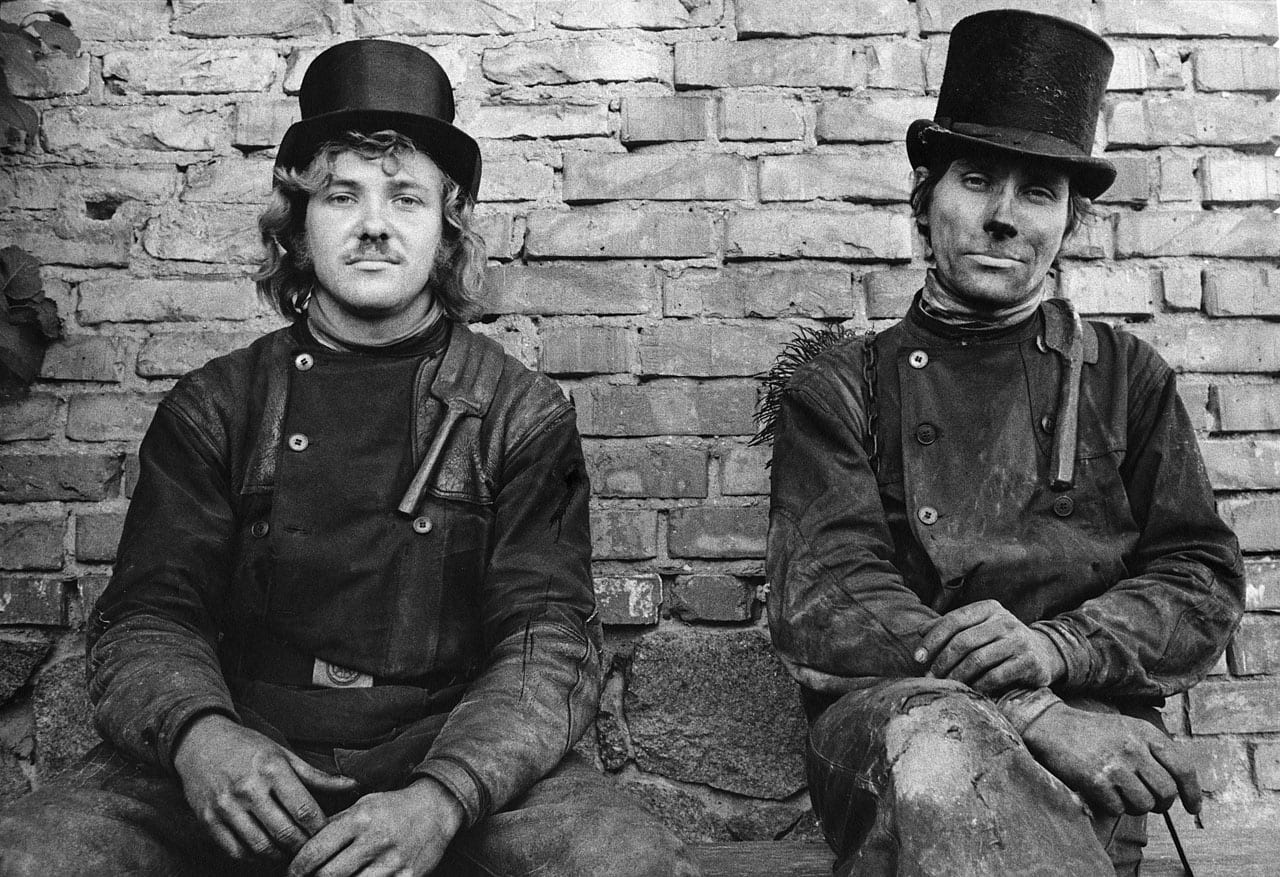

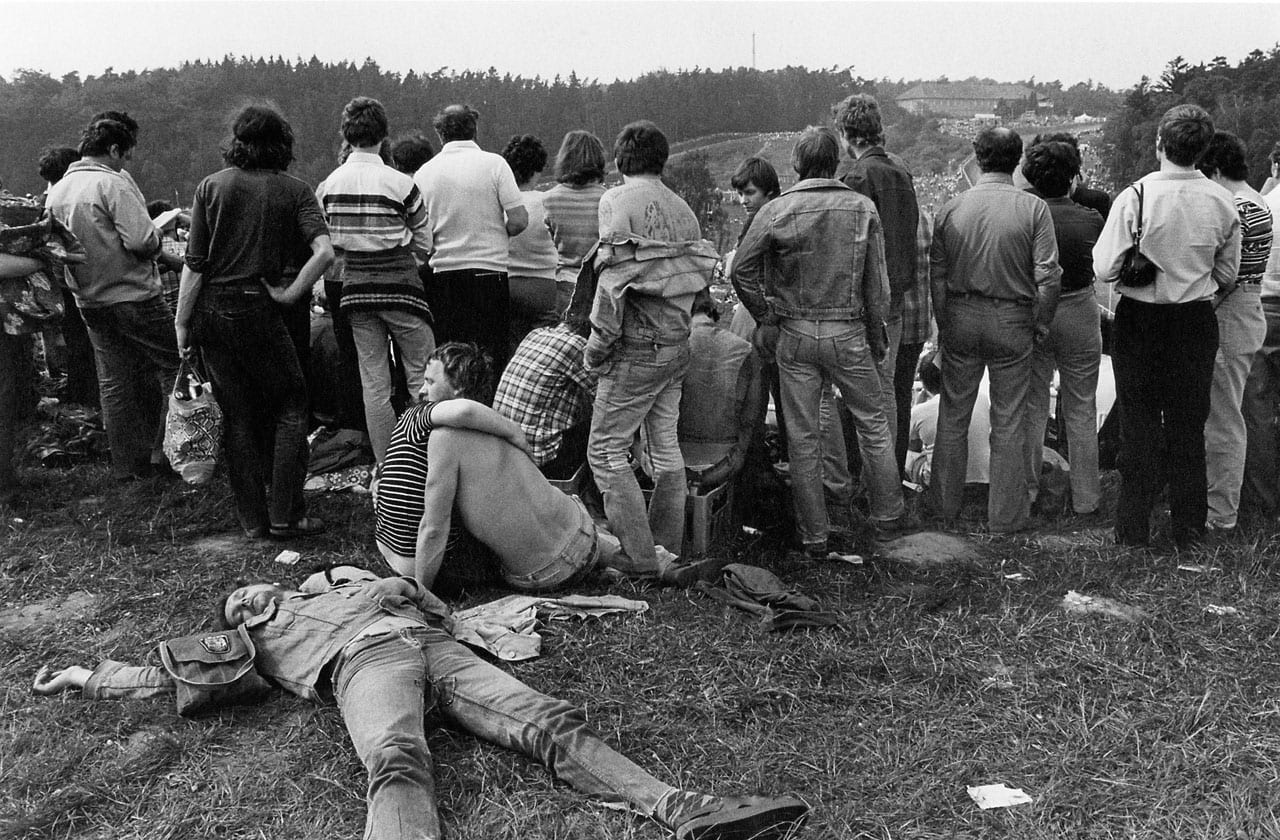

“When selecting the photographs for this volume, I placed no demands on myself, and certainly did not try to comprehensively depict working and living conditions in the GDR,” he later adds. “…they focus on the everyday, and not on the spectacular. In my photographs, I only rarely attempted to capture a decisive, unrepeatable moment. The moments I always searched for were the ones in which whatever was special, unusual or temporary about people and things had dropped away, revealing the core of their being, their essence.”

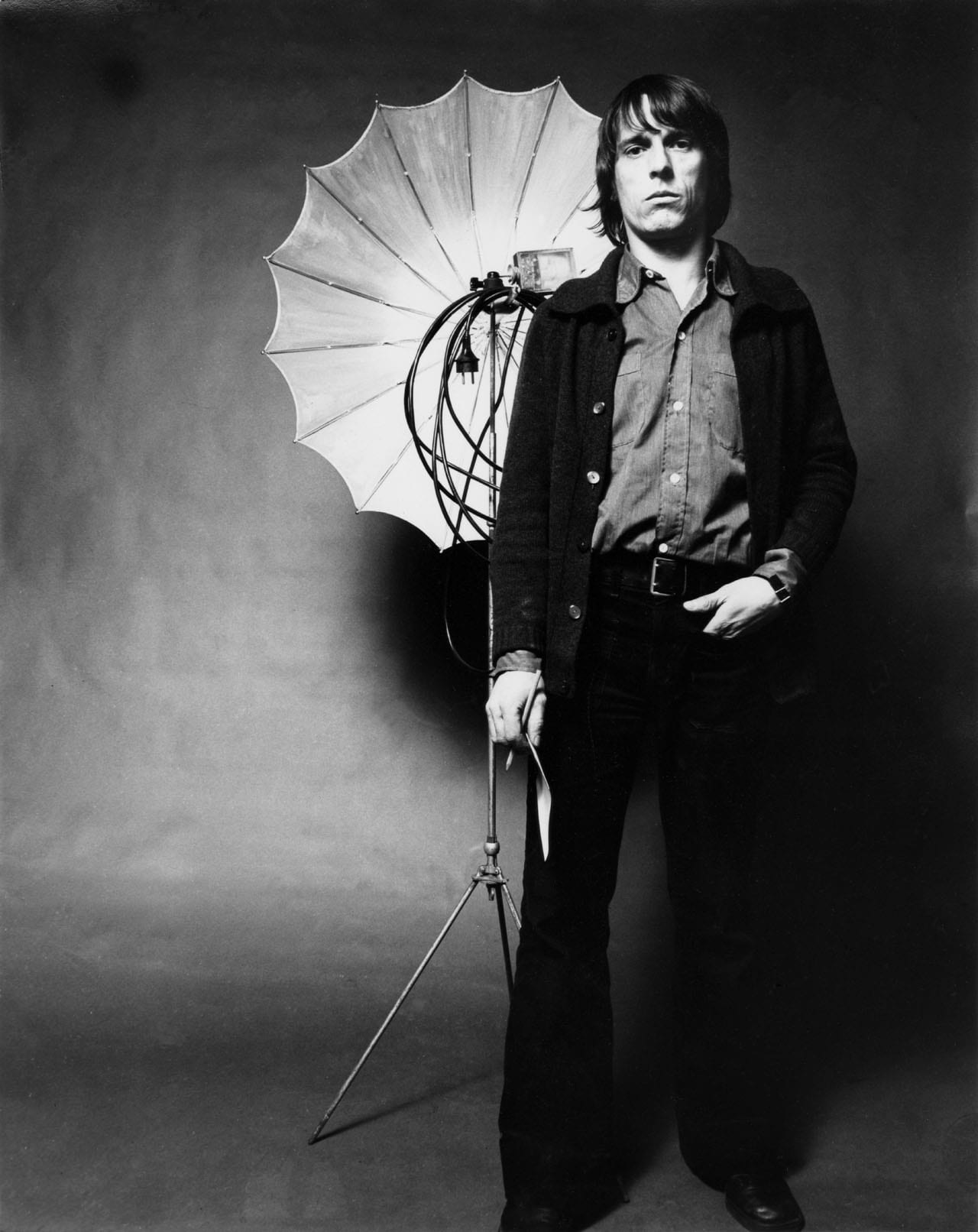

Born in Berlin in 1940, Melis grew up in an artistic family and decided to become a photographer when he finished school. He was keen to travel the world through journalism but, though early adventures with a deep-sea trawler took him as far as Greenland, he quickly found his wings clipped by the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961. His travel was restricted to Eastern Europe and the USSR, and East Germany quickly became his main subject.

First finding work with the arty, creative East German fashion magazine Sibylle – he later married one of its editors, Dorothea Bertram – he went on to be commissioned by East German publications such as Neue Berliner Illustrierte and the Wochenpost, and West German titles such as Die Zeit, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Süddeutsche Zeitung and Geo. The GDR titles exercised “rigid editorial control” but gave him access to otherwise inaccessible locations such as artisan and industrial zones, mines, schools, hospitals, institutes, offices and even Russian barracks; Melis also “took the opportunity to photograph the undesirable, the displaced and the silenced”, creating a body of work “that ended up consigned to a drawer”.

He was confident that this work would find an audience though, and it soon did, though it was initially restricted to just “a small community of fellow artists who shared an interest in a realist and aesthetically demanding style of photography”. Including photographers Arno Fischer and Sibylle Bergemann, this group came to be named Direkt, after documentary-maker Peter Voigt’s observation that people always looked directly into their cameras. Their “images of ‘exiled reality'” were rejected by the influential Association of Journalists and the Cultural Association, denounced as “rubbish bin photography” and therefore excluded from exhibitions, but the group persisted and eventually succeeded in founding a photography working group within the Association of Fine Artists in 1981.

“Our main objective was to have photography recognised as an independent art form, since we would then be able to gain access to a less tightly controlled audience,” writes Melis, who took on the role of chairman. But, he adds: “Eloquent art historians such as Peter Pachnicke and Wolfgang Kil, who were supporters of our working group, began talking about photography as art. They used their speeches and writings to give photography a new sense of freedom, changed how photography was treated in the media, and paved the way for so-called ‘rubbish bin photography” to be shown in minor and major exhibitions.

“Photo galleries were opened, catalogues were printed, and eventually newspapers and magazines began to report on photography. As a result, newspapers ended up printing images that they themselves had once commissioned but had rejected for political reasons. Moreover, photographers could occasionally access the travelling privileges that artists enjoyed, which in turn benefited photography‘s cosmopolitan nature and aesthetic standards.”

This turn of events was especially fortunate for Melis, because in 1982 he was blacklisted by the East German media, after taking photographs for Geo to accompany an article by Erich Loest – a dissident who moved to the West. “That incensed the editorial office at the Wochenpost,” writes Melis. “As a result, I never received another assignment from that newspaper or, by extension, from any other newspaper or periodical, because they all belonged to the single socialist publish- ing house monopoly, the Berliner Verlag.”

Instead Melis was commissioned to shoot a book by the publishing house Greifenverlag, and for this period was able to focus on books and exhibitions, as well as teaching at the Berlin Weißensee Academy of Art. “Taking stock of the conditions under which I worked in the GdR is no easy task,” he writes. “Opportunities to be published were limited, due to political censorship and the lack of an aesthetic sensibility on the clients’ part. I was able to complete many of the commissions I received from Western media with no trouble, such as record covers for Wolf Biermann. At the same time, the Stasi searched my house in Uckermark in the dead of night because they suspected me of having negatives of undesirable images.”

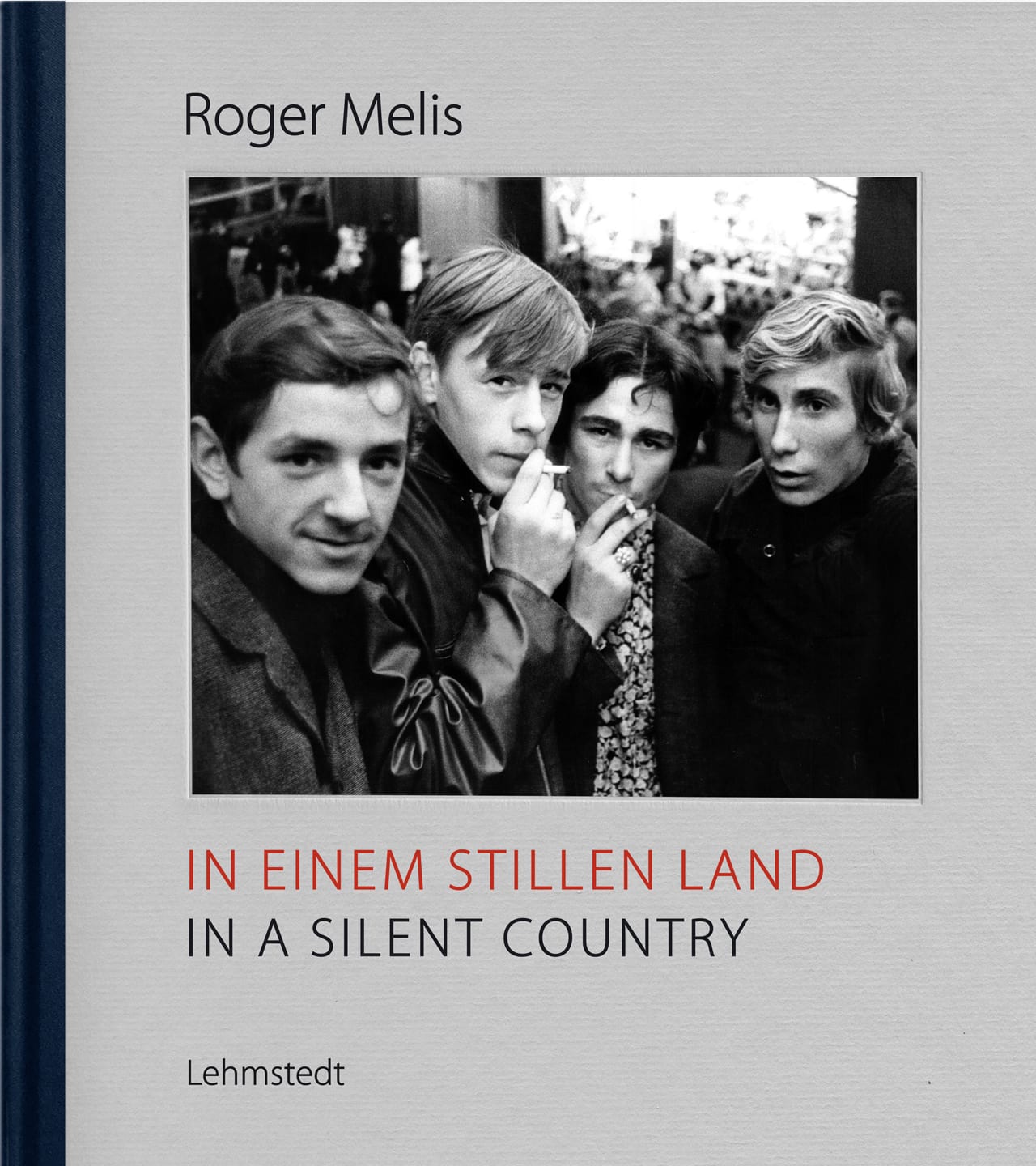

In 1989, after the fall of the Berlin Wall, he resumed his press career, working as a photojournalist and portrait photographer for Wochenpost, Die Zeit and Süddeutsche Zeitung; from 1993–2006 he taught photography at the Lette Verein in Berlin. The idea for In a Silent Country came about at the turn of the century, and it was first published in 2007 to huge success, greeted with acclaim by critics and reprinted three times in its first three years. Its launch was accompanied with exhibitions across Germany, including a retrospective in C/O Berlin, the gallery’s first exhibition of an East German photographer, and a show which drew more than 16,000 visitors. Sadly Melis died before it opened in 2009, just short of his 69th birthday. This edition of In A Silent Country is the first to be published with an English translation.

“My most important task has always been to create powerful portraits of people, whenever possible in their natural living and working environments, and to avoid stealing their souls and instead to approach them sensitively, remaining – and I use this antiquated expression deliberately – in awe of the individual, a respect which the police and the Party secretaries also deserve,” writes Melis in his introduction. “You cannot choose the yardstick by which you are measured, but if I could, it would be this one above all.”

In Einem Stillen Land, Fotografien 1965-1989; In a Silent Country, Photographs 1965 – 1989 by Roger Melis is published by Lehmstedt (ISBN 978-3-937146-52-2), priced €28 https://lehmstedt.de/melis_stilles_land.htm