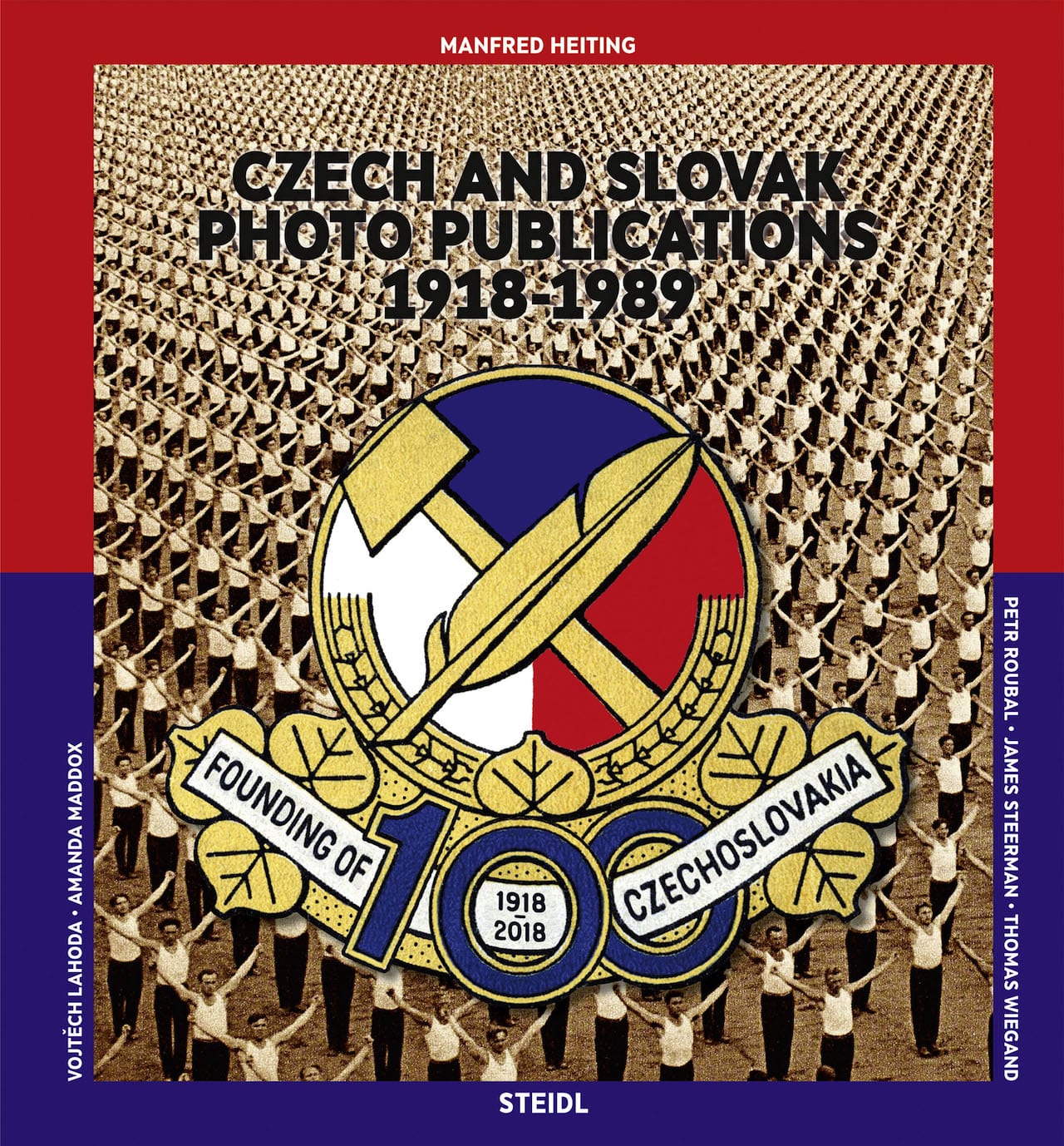

Originally trained as a typographer and designer, Manfred Heiting joined Polaroid in 1966. Meeting Ansel Adams shortly afterwards, he was inspired to start collecting photography, amassing a world-class collection of prints which was acquired by the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston in 2002. He also started collecting photobooks in the 1970s, turning to it in earnest in the 1990s and creating a library that was considered one of the most complete in the world, including a copy of most of the important photobooks that appeared from 1888-1970 in Europe, the United States, the Soviet Union, and Japan. This collection formed the basis of several compendium books published by Steidl, including “Autopsie” – German Photobooks 1918-1945, The Soviet Photobook 1920-1941, and The Japanese Photobook 1912-1990 – but sadly, it was decimated in the California wildfires of 2018, when it went up in smoke along with Heiting’s home in Malibu. As Steidl publishes a new book by Heiting, titled Czech and Slovak Photo Publications, 1918-1989, BJP caught up with him.

British Journal of Photography: How did you get into photography in the first place?

Manfred Heiting: I met Ansel Adams in around 1967, and he taught me what a perfect print is, and most importantly, to have respect for the photographer’s image selection, dark-room-print-quality, and the cropping of a print (or not – “…do not cut pieces off to fit a design…”). I was grateful for his advice and passionate about it ever since (and as a designer, always “lived” by his rule). In building my encyclopedic collection of photographic prints, and in a similar way my book collection, I was always guided by his unique and high standards. He was a great mentor and I am always indebted to him for being able to stand on his shoulders.

I started to buy photobooks to educate myself in the mid-1960s – I do not consider this collecting, but I acquired about 7000 books that way through the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. In the beginning of the 1990s, I was more focussed and looked for specific books published after the invention of the half-tone process (in around 1886), as complete as they were published, and in as perfect as condition as I could find. This of course also meant that I often had several copies of the same book, because I found a ‘better’ copy later. This was the time I consider now as collecting.

BJP: Your collection largely focused on books published in Europe, Soviet-Russia, and Japan, why was that?

MH: Until World War Two, most of the better photobooks came from, or were published, in those countries. Of course, there are some great American photo books before World War Two, and naturally, the books and magazines that included illustrations in the photogravure process, such as Camera Works or the books by Coburn, were stunning, and I treasure those. But all in all, the output was a far cry from what was published elsewhere. Paper manufacturing and printing processes where all invented and improved, to incredibly high quality, in those countries.

BJP: What are you interested in when collecting photobooks – do you think of the books in terms of historical interest, or aesthetic, or both?

MH: Aesthetics, and craft. Ansel Adams has stated that photography is like music – the negatives are the notes, the print is the performance. On that basis, I would argue that to perform music to a large audience you need an orchestra, with all its instruments; to present photography to a large audience, you need a photo book with all its contributors – the writer, editor, designer, typographer, printer, binder, and of course photographer. That is what I am looking at when selecting a photobook, and naturally the subject matters as well.

BJP: You’ve put together books on German, Japanese, Soviet-Russia and now Czech and Slovak photobooks. Germany, Japan and Russia seem more obvious, why did you want to do something on Czech and Slovak books?

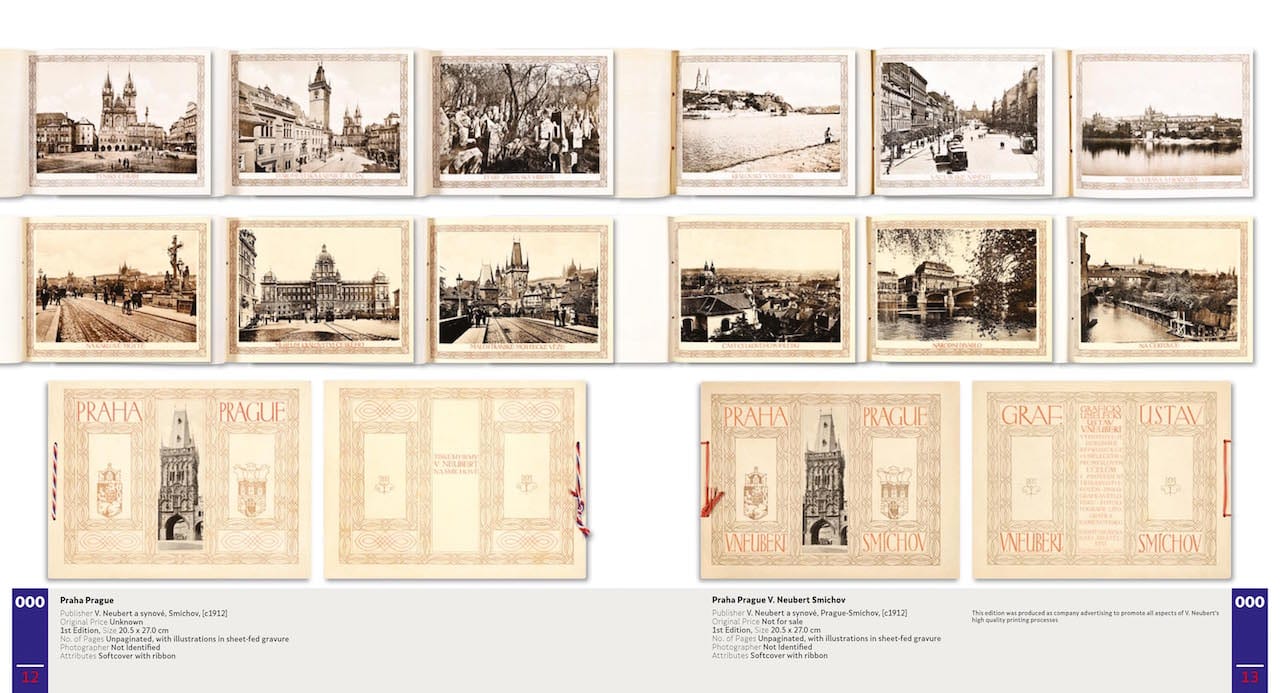

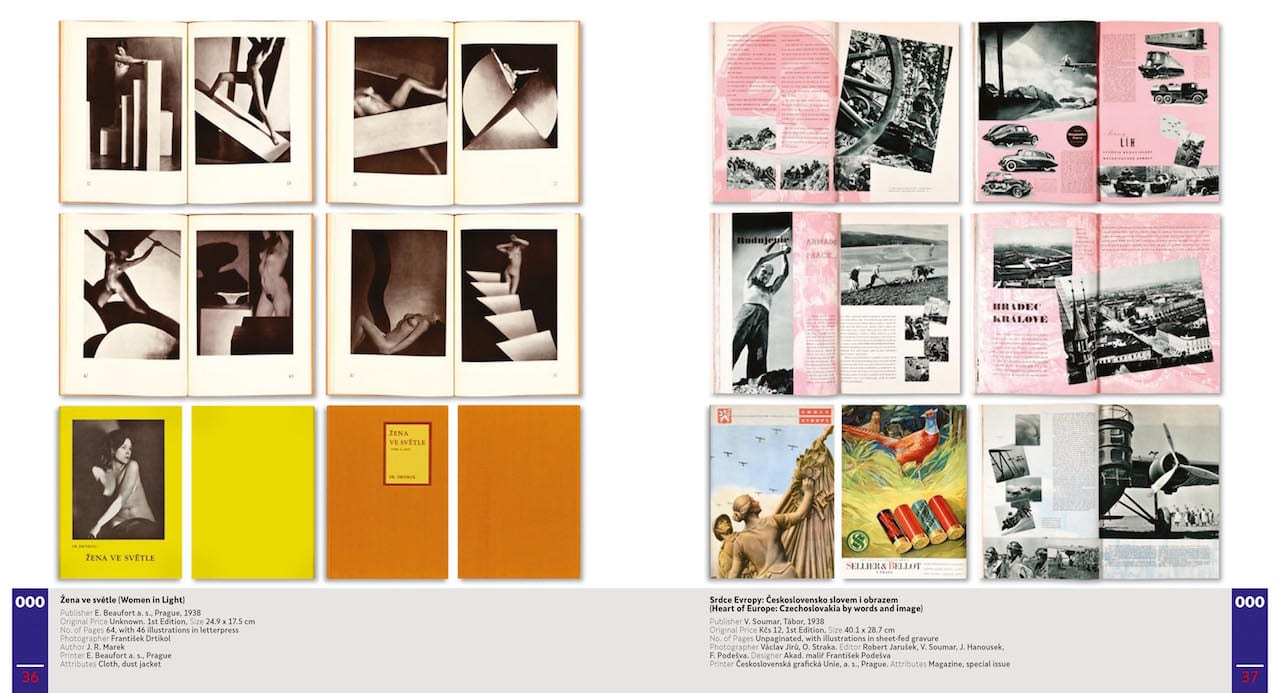

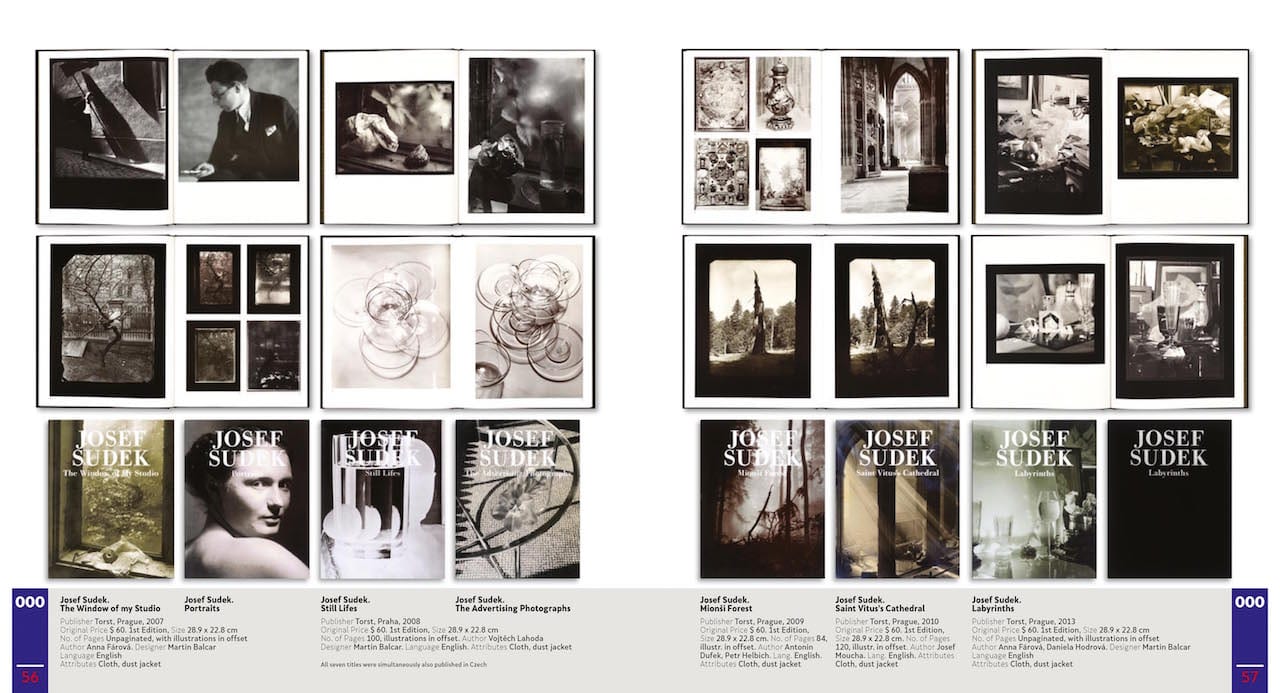

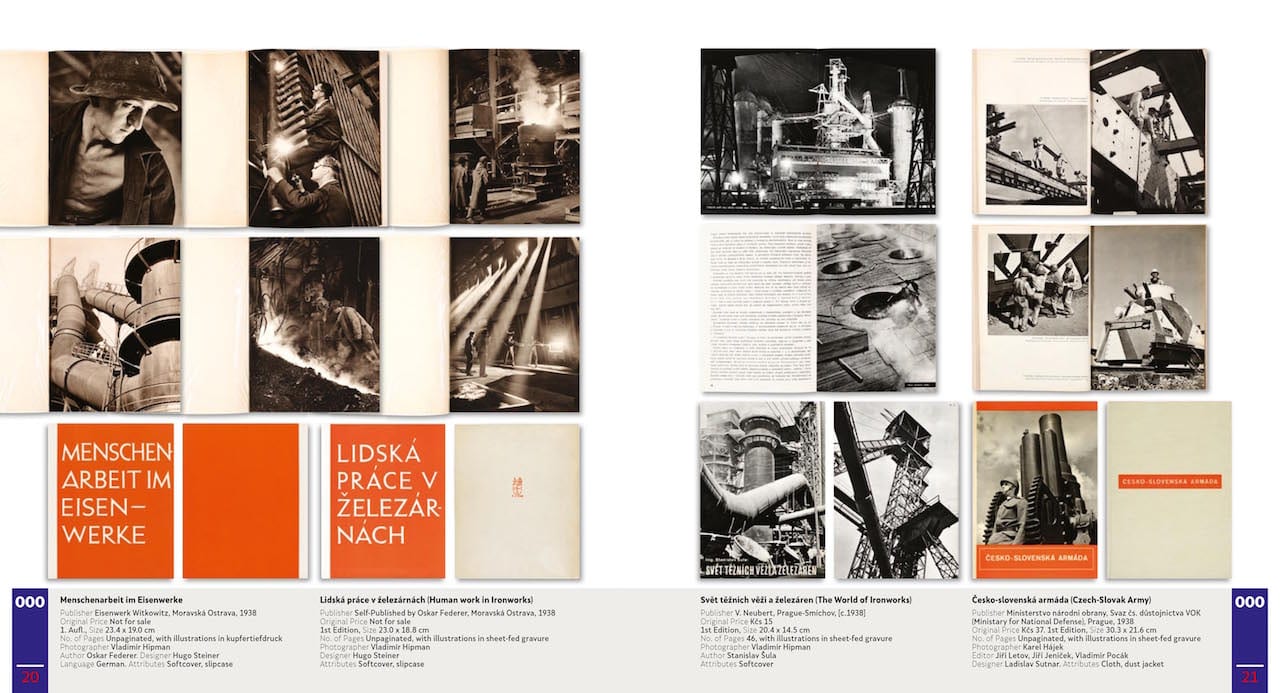

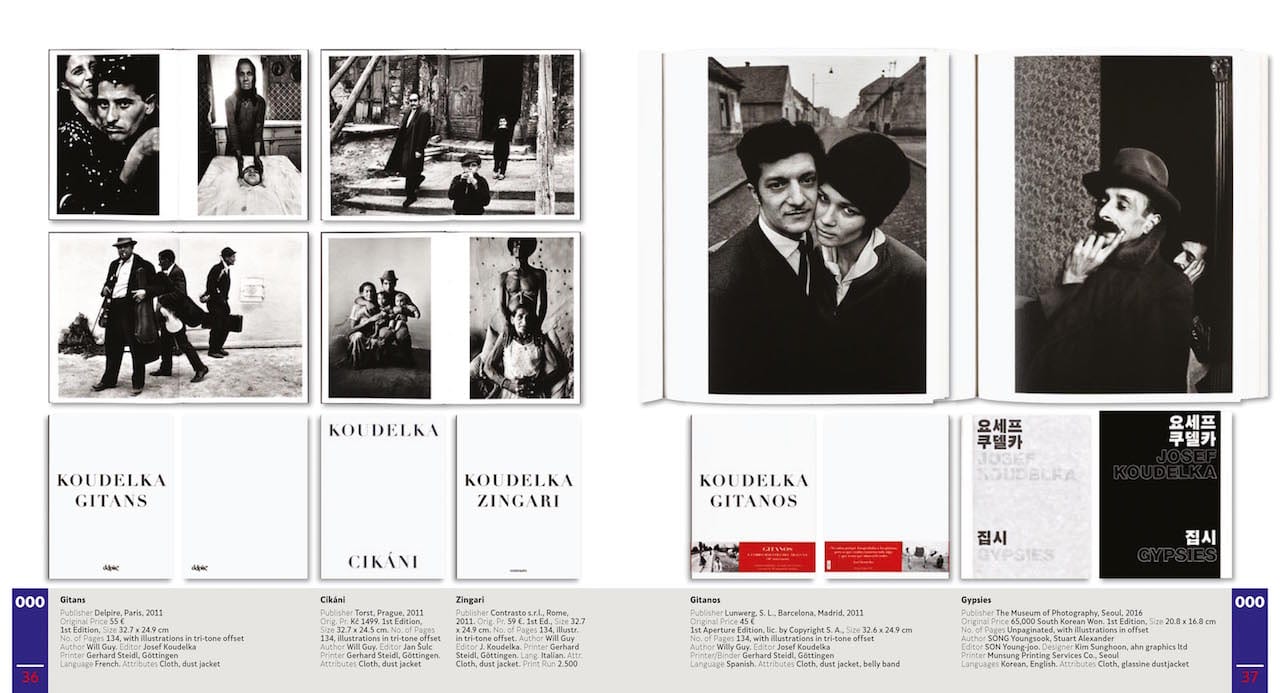

MH: Czech and Slovak photographers made an important contribution to our field – Funke, Dritikol, Sudek, Styrsky, Rössler – of course Koudelka – and many more, are all giants known in the West. But most of the photobooks made there are not so well known, particularly the ones from before World War Two – and are a testimony of the highest quality in creativity and craft.

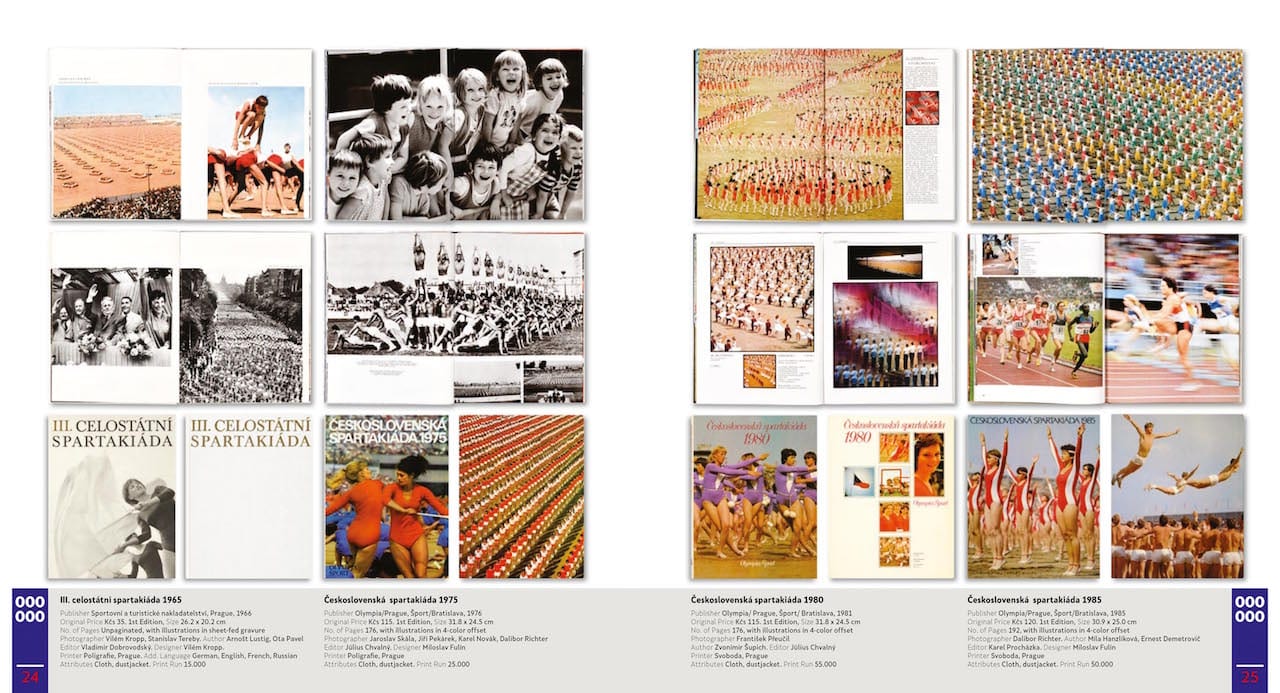

BJP: Why did you choose to focus on Czech and Slovak photobooks from 1918-89?

MH: Czechoslovakia was founded in 1918, and 1989 was the days of the Velvet Revolution and the end of the communist regime. In some way the photobooks published there after 1989 became like all Western photobooks, and lost most of their local identity and quality – they may have been made more for “us” than for “them”.

BJP: How do you decide the time-frames you cover? For example, the Japan book covers 1912-1990, the Soviet 1920-1941, do the time frames just suggest themselves? Is there a reason you haven’t included more contemporary work?

MH: First we have to except that after the 1970s most photo publications looked alike – printed (colour) photographs, one on a page, each with a white border . . . . Most contemporary photo publications are not important enough to have an effect on history – and there are so many. Maybe the photographs they show are sometimes the exception, but as books – in terms of the design, layout, type, graphics, printing, binding, text, and so on – no effort is being made.

Also, because of limited paper and printing techniques (all invented and improved in Europe), most influential books and publications happened before World War Two in Europe, in Japan a bit later – particulate – very important – in the 1960s. Art and Design movements such as the Bauhaus, and thousands of illustrated magazines made photography the medium of choice between in Germany and beyond – between 1920-1940 every famous photographer, including Moholy, Munkascki, Brasssaí, Kertesz, Pecsi, Umbo, Eisenstaet and their like, made their debuts in magazines – mostly German magazines.

In Soviet Russia nothing was published before 1920, as there was no paper, no printing machines, no printers, binders, and so on. The first publication about the 1919 revolution was published in 1920; when Nazi Germany invaded Soviet Russia 1942, everything stopped.

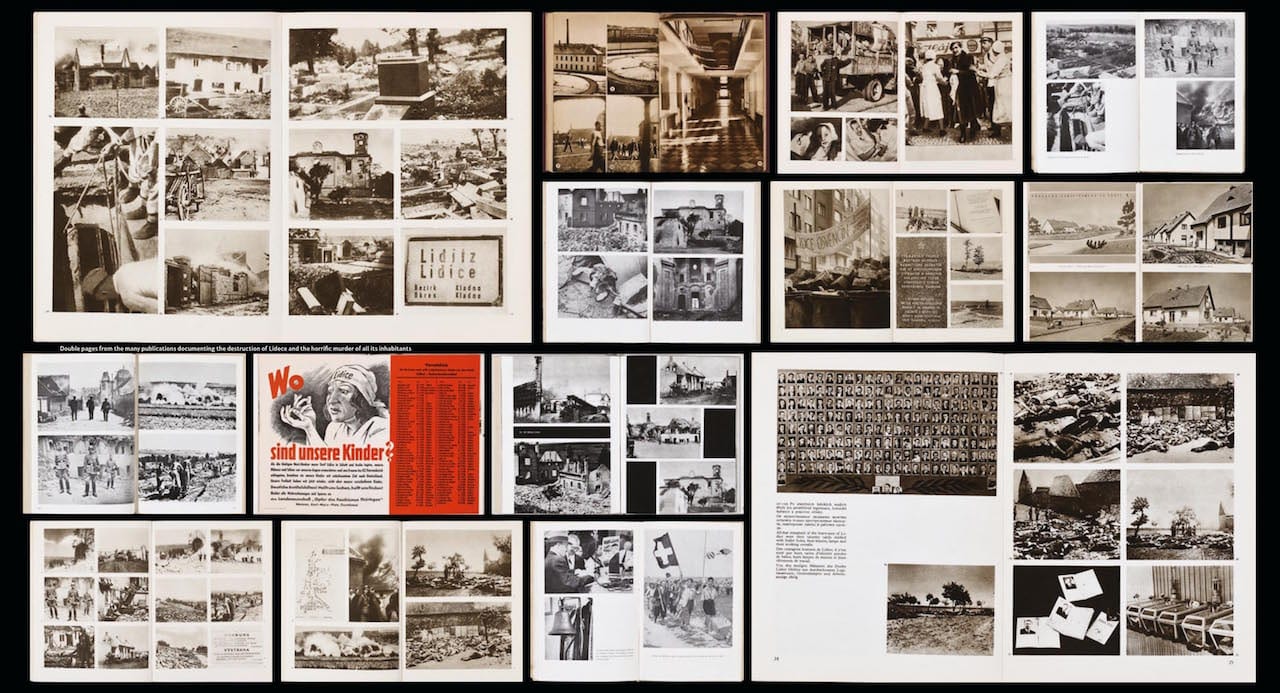

BJP: The publications included in Czech and Slovak Photo Publications feel really comprehensive – over 800, and including documentations on human suffering from the Nazi era, catalogues of meat products, and books about cats, as well as well-established photographic greats. How do you choose what’s included and what’s not?

MH: The selection should include all the various subject matters, as well as variations in book design and book categories, but also – and always – be about photography during these periods. The historic documentation in the book of what happened in this country [during the Nazi occupation] is nearly incomprehensible, so I wanted to show this as well – so we never forget. Of course there are more publications, I have tried to show what quality was possible in photography, design and printing. Even with 800 photobooks, it is only a selection representing the enormous spectrum of photography in Czechoslovakia, and the Czech and Slovak Republic.

I do feel that in our world we seem to concentrate too much, if not always, on art photography, which is the least of my concerns. The most appealing, often stunning, achievements of photography in the 20th century were in commercial, advertising, and fashion photography – and important work made by all the great photographers, from Walker Evans and Robert Frank, to Richard Avedon and William Klein, was work made for companies for product advertising, annual reports, and commemorative publications.

BJP: Some of the spreads from books on the Nazi occupation are quite shocking, did you have to make some decisions about what to include and how to represent it?

MH: Well, yes. This is not a catalogue raisonnée of the Nazi atrocities, nor the Czech photobooks showing them. But I hope I got the message across.

BJP: How many of the books in Czech and Slovak Photo Publications come from your own collection?

MH: There were only a few books I did not have at the time – now it’s different. Many were going to be transferred to the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston [which had acquired a selection of about 20.000 books from my library prior to the wildfires], but until 2023 they were in my house in Malibu for me to complete my research and documentation. All in all, I had about 1800 photo books relating to this country.

BJP: We were terribly sorry to hear about the destruction of your library in the wildfire. Have you been able to rescue anything, or is the whole collection lost? Was any of it digitised?

MH: Yes, it is devastating and certainly a great loss, and not only for me personally. A portion of my library was already legally owned by the MFAH, but contractually still in my house until 2023 for further research, and for my book projects. Although my own books were not insured, the ones on the museums transfer list were insured by the museum and we are now planning and working on the replacements of most of the lost books.

95% was digitised, and I had my low-res database with me in Europe where I was when the fire happened. With the latest technology it is now possible to convert low-res into high-res, so I can continue to work on books [Heiting is currently working on forthcoming publications on the bibliography of Dr. Paul Wolff and Dutch and – possible – French photobooks]. I still have the knowledge and know where books are [in other libraries and collections] when I need them. I will continue to collect and look for publications that are “complete as published” and in fine condition. Also, for me, it was not always the catch, but the hunt.

Czech and Slovak Photo Publications, 1918-1989, edited by Manfred Heiting is published by Steidl, priced €125 www.steidl.de