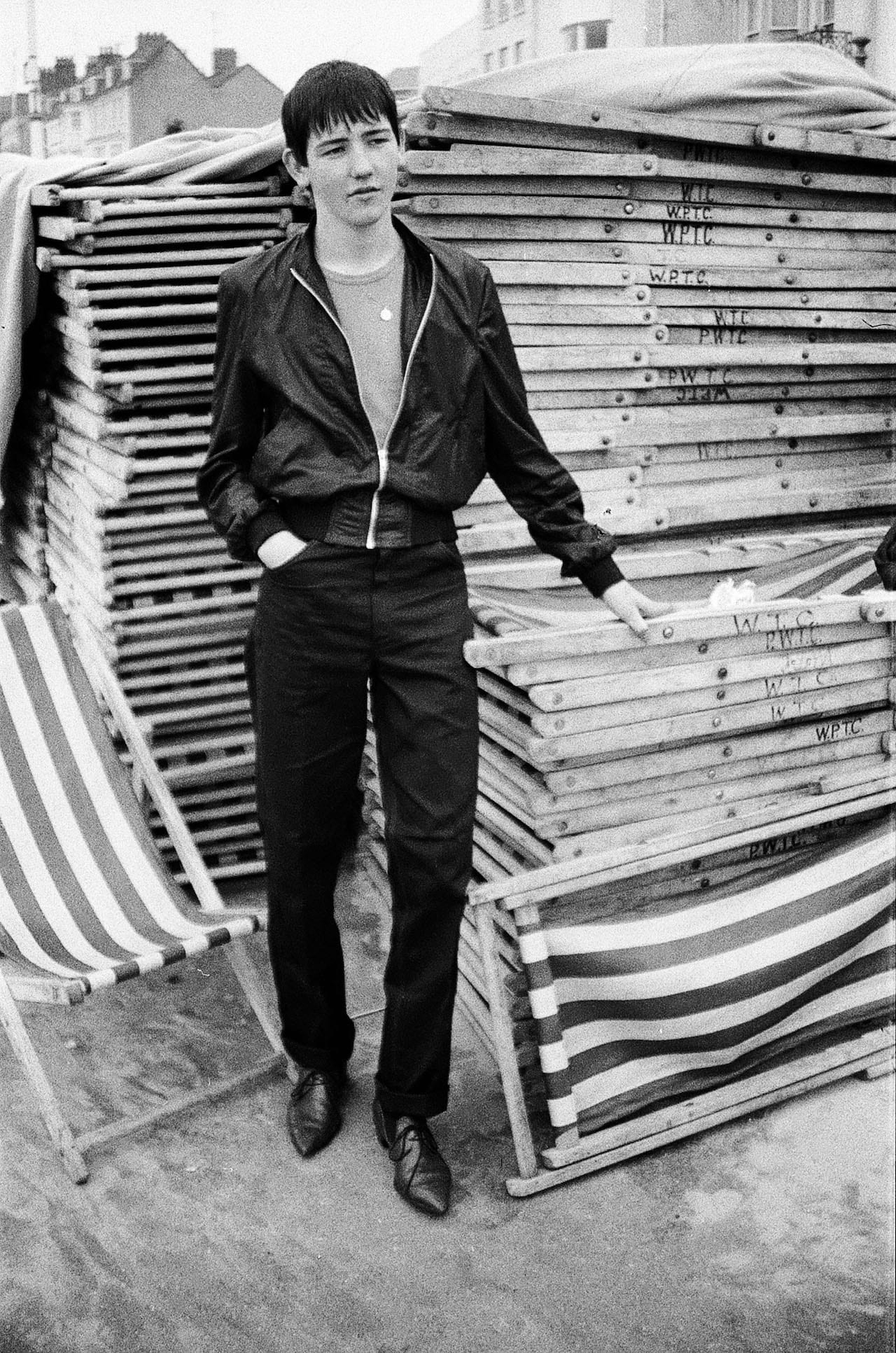

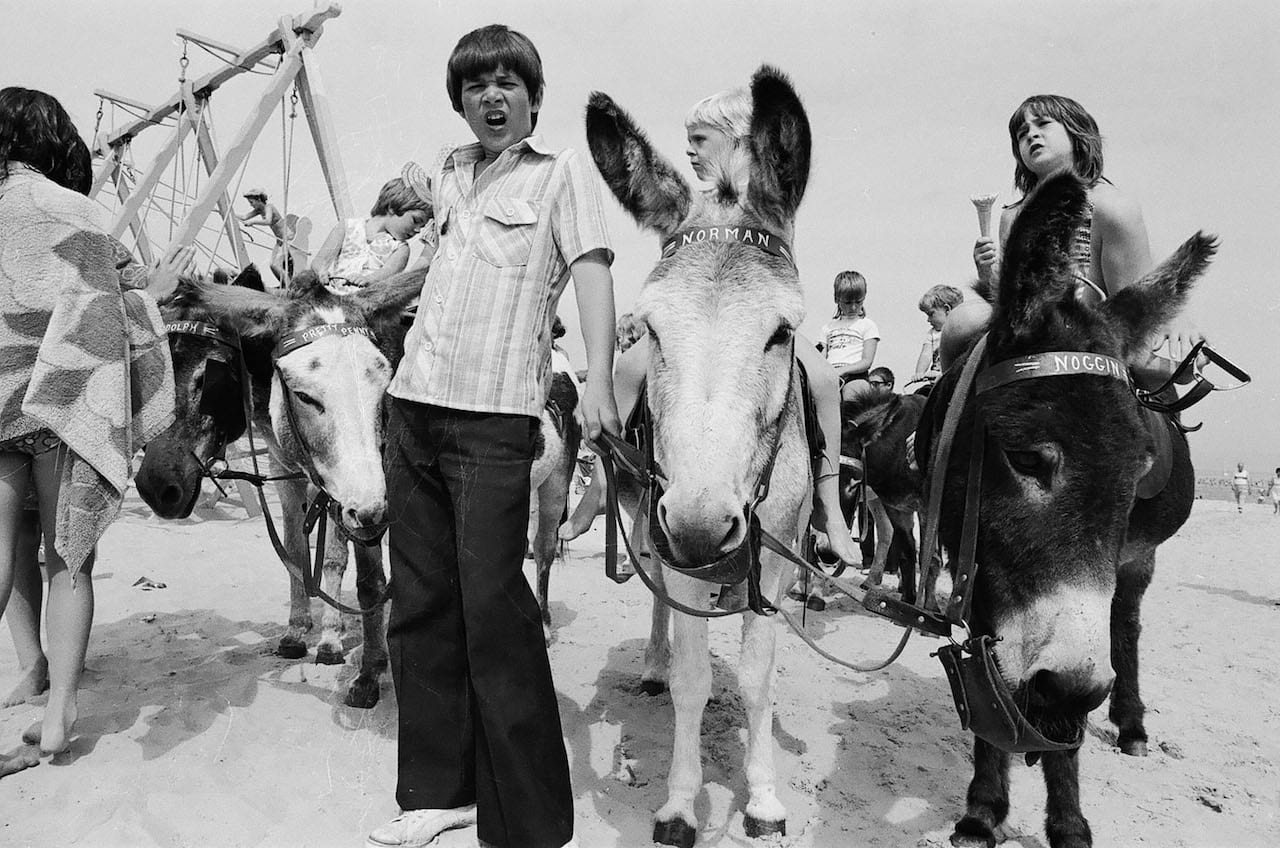

It’s the summer of 1976 in Weymouth, England, and 19-year-old Iain McKell is working the length of a busy seafront with two cameras strung round his neck. One is for his summer job, which is to sell portraits to sunburnt holidaymakers for £1.50 a print. The other is for a personal project, which now – 43 years later – is on its way to being published as a book, Private Reality: A Diary of a Teenage Boy.

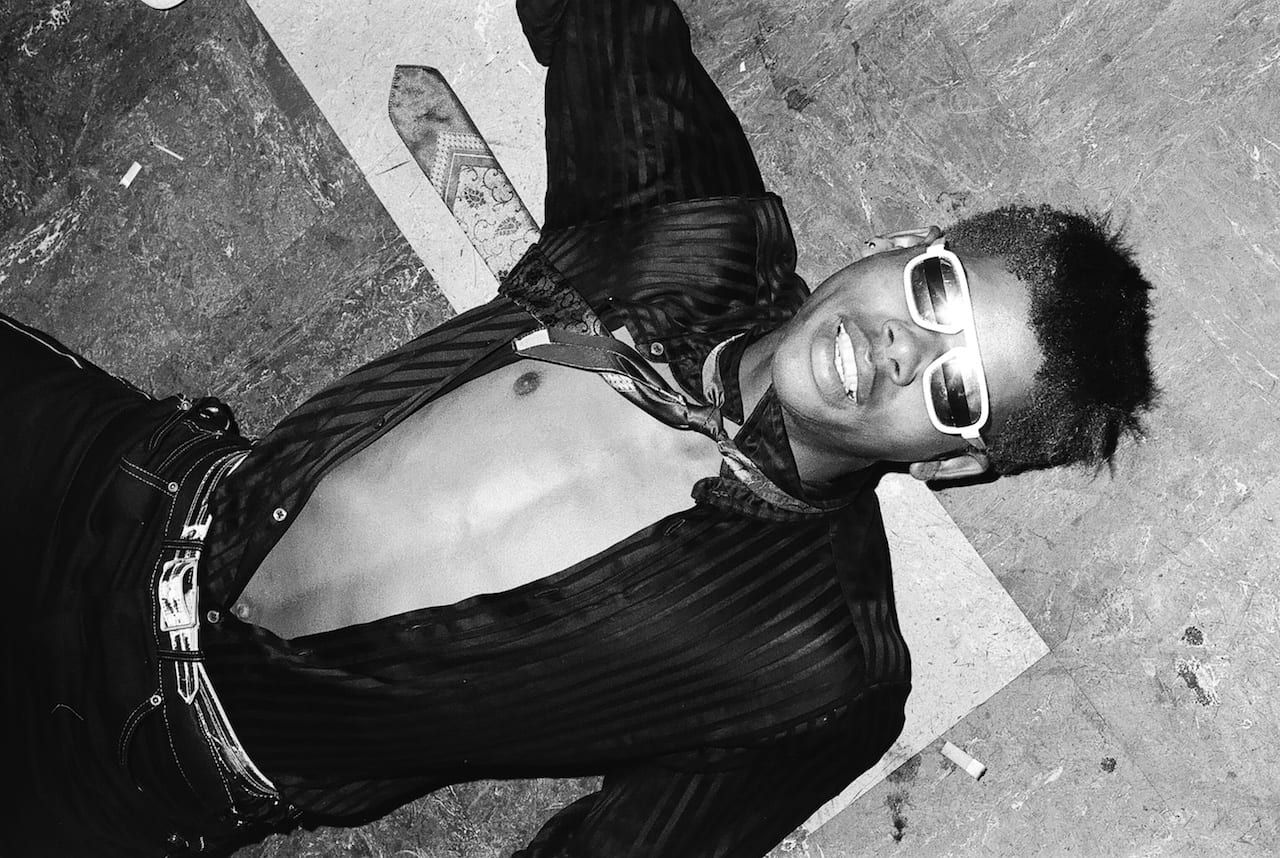

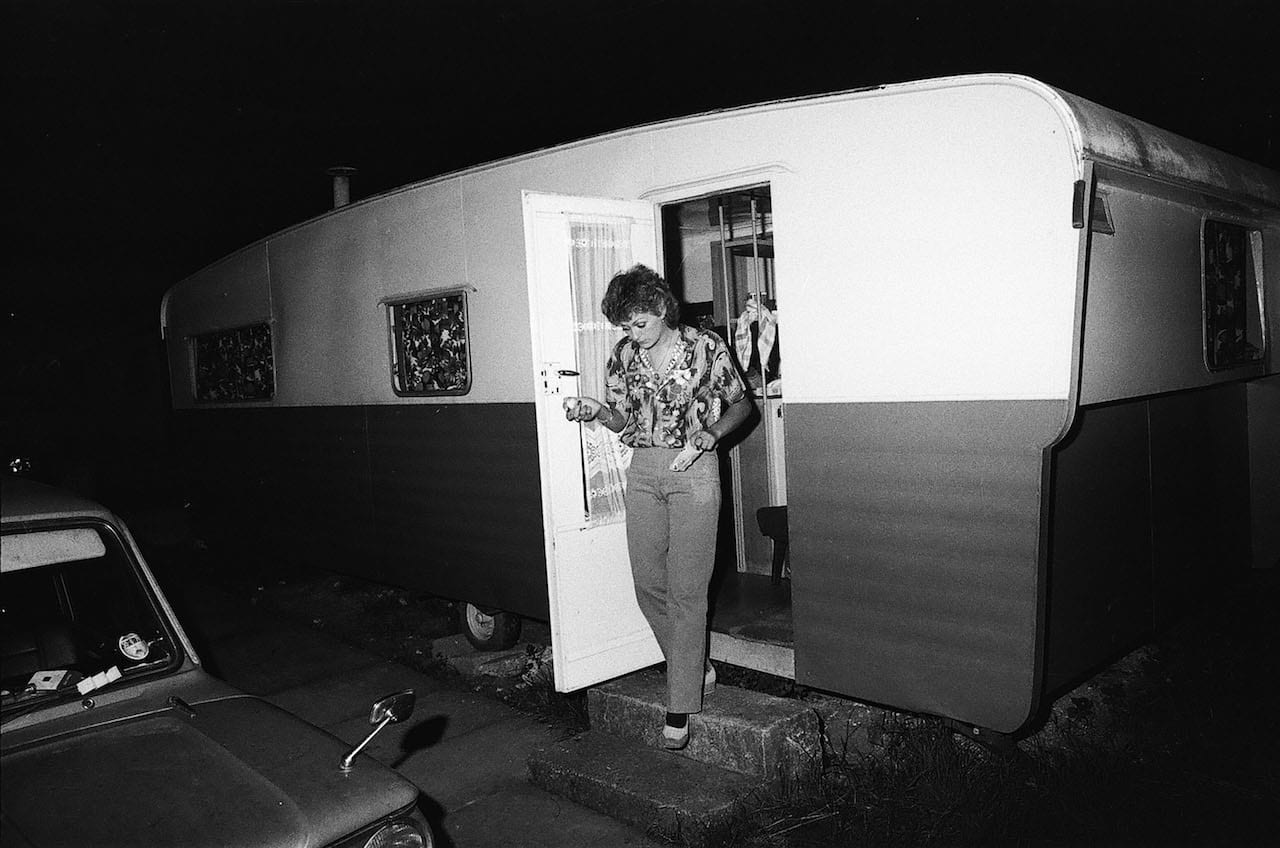

Back then McKell was making photographs of everyone, not just sunburnt holidaymakers, but also friends, family, and the Weymouths. His camera went everywhere with him – to the arcades, the caravan parks, down the pub, and even to the discos. His friends had no idea what he was doing, he says, but then to some extent neither did he. “We were all partying and having fun, but somehow, I had my eye on the prize,” he says.

McKell is now half way through a month-long campaign on kickstarter to raise funds for the book, and plans to publish it this June in partnership with Dewi Lewis. In May some of the photographs will be shown in an exhibition curated by Val Williams and Karen Shepherdson, Seaside: Photographed at Turner Contemporary in Margate.

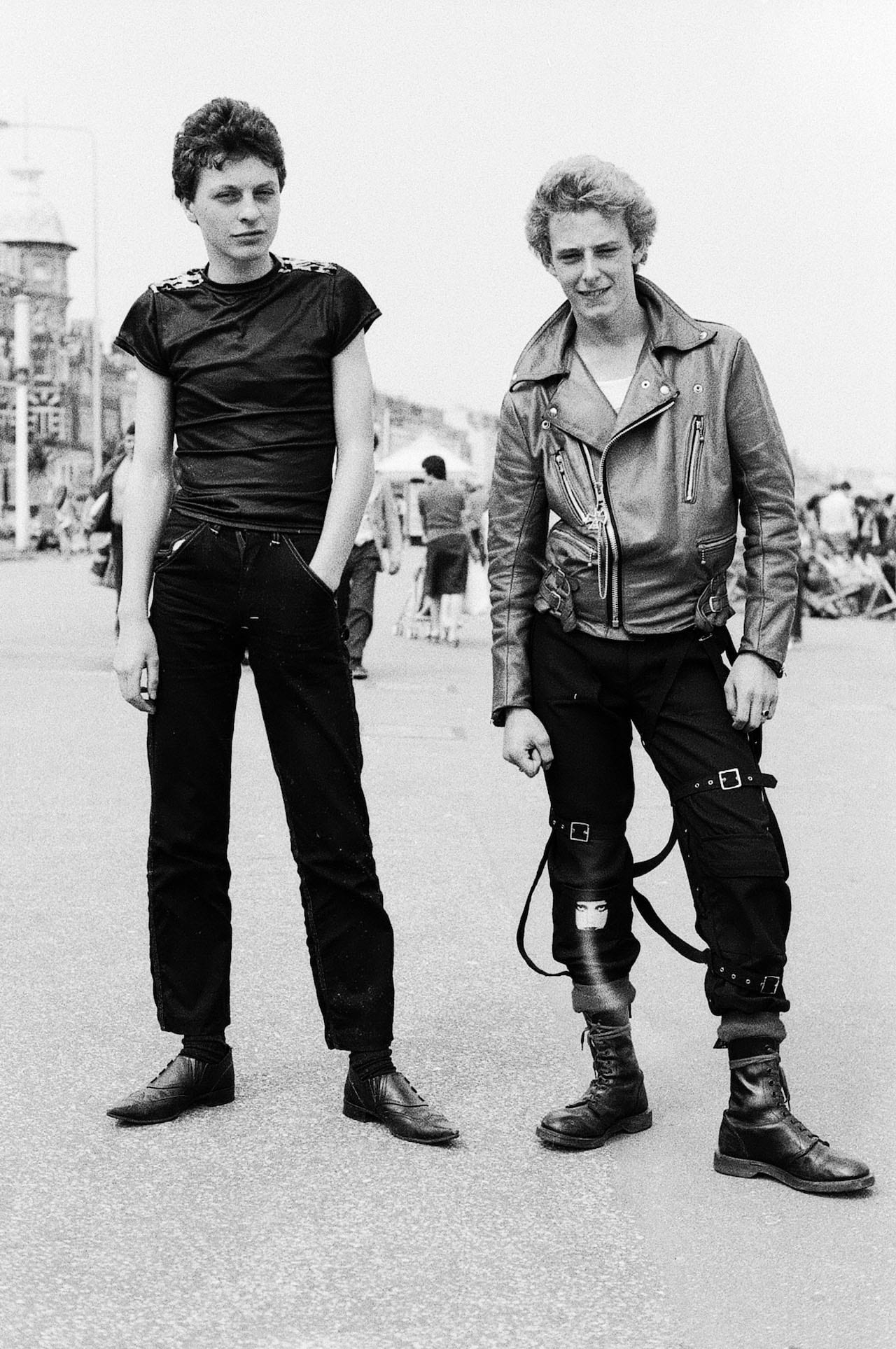

Along with his images, McKell will be exhibiting a dummy book that he made when he was 19; rediscovering it was part of the motivation to finally publish the pictures. He had named the dummy Private Reality, and inside it are handwritten notes of details he most likely would have forgotten by now. “Malcolm is 19 and lives at home with his mum,” he writes, and “the boy on the right is 15 and hasn’t been to school for a year”.

Both the photographs and notes reflect McKell’s own feelings of existential angst as a teenager on the brink of adulthood, probably driven by his novel of choice that summer – A Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger. But it also speaks of a time in which youth subcultures were radically shifting, with punk taking over from the era of free love.

“In 1976 the Sex Pistols swore on TV, then The Clash released White Riot, and suddenly the hippies were gone. Everyone had cut off their long hair and made it spiky,” says McKell. “But small town subcultures are funny, it’s not like bigger cities where you effectively have tribes. In a small town like Weymouth, one guy in the group is a hippy, another is a skinhead, and another a rocker. It’s the backwater, and it’s always been behind the times, but within that you get little nuggets of interesting people”.

McKell himself identified with punk, aesthetically but also in terms of worldview. “I flirted with a bit of eyeliner,” he says, “but it was more in the attitude of my images”. He never hesitated to take a photograph and was playful with his approach, for example with his series of images of people watching the sunset from their cars. “It was like shooting fish in a barrel,” he says, describing how he jumped in front of each vehicle. On his last shot a woman came charging out, hitting him with her handbag, but McKell continued to take pictures. “Now that was punk!” he says.

Since the 1980s, McKell has photographed various subcultures in the UK, from skinheads to punks to the Blitz Kids, rockabillies, and gypsies. They all appeared in his 2012 book Beautiful Britain, along with photographs of supermodels, the gentry, squats, and rural raves, covering many eccentric facets of British identity. Most recently, McKell shot project on a community of young women sharing a warehouse in East London, which will be published this March by Hoxton Mini Press as New Girl Order.

But none of these personal projects would have been possible without the many years he spent grafting as a commercial photographer – McKell has shot fashion spreads for magazines such as L’uomo Vogue, i-D, and The Face, produced films for Vogue Italia, and photographed A-listers such as Madonna, Kate Moss, and Lily Allen. But he’s moved away from this work now, moving to east London, building himself a garden studio, and renting out spare rooms to cover his living costs. After 17 years of living in west London and raising his daughter, now 22, as a single dad, he wanted to “focus on me”. “I’ve got a mission, and a project to do, and I want it to be successful,” he says.

McKell comes across as energetic and animated, even over the phone. He is incredibly talkative, jumping from conversations about his photography and the kickstarter campaign, to discussions on quantum physics and the illusion of consciousness. Still, he never strays too far from the central thread to the conversation, which is his passion for image-making. “Since a really young age, I had this desire to be an artist, to make things,” he says.

At ten years old, drawing was the one thing that would get him out of bed in the morning; he recalls making pop-art style copies of images on postcards that he had bought with his parents when they visited Carnaby Street in London. The drawings were of bikers and hippies, which oddly foreshadows his interest in subcultures and rebels further down the line. “That was the beginning of something, that idea of identity,” he reflects.

McKell has never been afraid of talking to strangers or being in unusual situations, which is perhaps thanks to his upbringing in a hotel. When he was two, his parents took over the Channel Hotel on the Weymouth seafront, and then later moved to the Streamside Hotel just out of town. “Strangers were always in my life,” he says. “It was like a party all the time! There was all this energy constantly going on, and noise, and activity, and buzz, and stimulation. I found it really weird going to my friends’ houses, I couldn’t stand the silence. The quietness was quite disturbing to me.”

McKell’s entry into photography was through art, but at school he was never really interested in studying – instead of doing his O-Levels, McKell hitchhiked to Germany to pursue a romance with an exchange student he had met in Weymouth. Luckily the holiday romance fizzled, as they tend to, and when he got back he managed to get an A-level in Art. He went on to study Graphic Design at Exeter College of Art and Design.

“I really worked like a demon, I worked my arse off! Because I was happy,” he says. “I was so hungry, so demanding, I wanted to know everything, and I think that’s your opportunity, it’s your rite of passage. I went from being this loser running around Germany pursuing romances to, well, actually, not having a clue what I was doing.”

McKell’s time in Exeter had a huge impact on his career, he says. “I understood, through proxy, what fine art really was, but it was only when I started making photographs that it all started to make sense.” Recognising similarities between drawing and photography, in composition and perspective, “I just got it,” he says.

Soon after his first photography class, McKell saw an exhibition of work by Diane Arbus, and something clicked for him then. “When I looked at her work, I had an immediate understanding. It wasn’t so much about the content of the images, the images were actually telling me more about her, than the person in the picture. She was an artist and these were muses to her expression.”

McKell began to use photography as a way to make sense of the world around him, and “it was like a floodgate had opened”. At the time, he didn’t see photography as the end goal – he didn’t know if they were just images, or a reference for a painting – which explains some of his more graphic photographs of doors, or people sleeping in a heap on the beach. “It was that sense of abstraction I was looking for,” he explains. “It’s about image-making, and the process of that.

“Some photographers are happy with just the tag of ‘photographer’, like they are too modest, shy or insecure or even uncomfortable to say they are actually an artist,” he continues. “It’s like how Helmut Newton said he was a hired gun, like a Samurai warrior, or a Magnificent Seven cowboy, a romantic idea of an outsider from the main art world.

“I totally don’t think that that’s what I am, a ‘photographer’. I’m an artist, and I’ve felt that inside me since I was a child, but it was through the medium of photography that I found myself,” he adds. “I’m an artist first and a photographer second, I have no hesitation in saying that, as that’s how I’d like to be remembered when I’m gone, as an artist. Now that’s really romantic.”

www.iainmckell.com/ Iain McKell is currently raising funds to publish his book, Private Reality: A Diary of a Teenage Boy, which will be published in partnership with Dewi Lewis this June. https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/privatereality/private-reality-a-photo-book-by-iain-mckell

A selection of work from Private Reality will be shown as part of Seaside:Photographed at Turner Contemporary in Margate from May 2019 www.turnercontemporary.org/