Imagine being told by your mother that you are the result of rape. Imagine finding that your biological father sexually abused and murdered countless other women. Imagine being told that he was not the only one. Indeed, numerous men raped your mother. Imagine if this traumatic experience had resulted in your mother facing stigma and exile in her own community, and her family. Imagine suddenly understanding the rejection you had experienced growing up – why strangers called you “a child of the killers”.

A quarter century ago, over the course of 100 days between April and June 1994, an estimated 800,000 Rwandan citizens from the Tutsi clan were murdered or maimed by their fellow citizens – mostly by government-backed Hutu militias. As the international community stood by, thousands of Tutsi women were violently and repeatedly raped by the Hutu militia, prompting the UN to finally recognise rape as a weapon of war. An estimated 20,000 children were conceived during this genocide throughout the central African country, and almost all of them were raised alone, o en without family or state assistance. At some point, the women had to tell their children of the circumstances in which they were brought into this world.

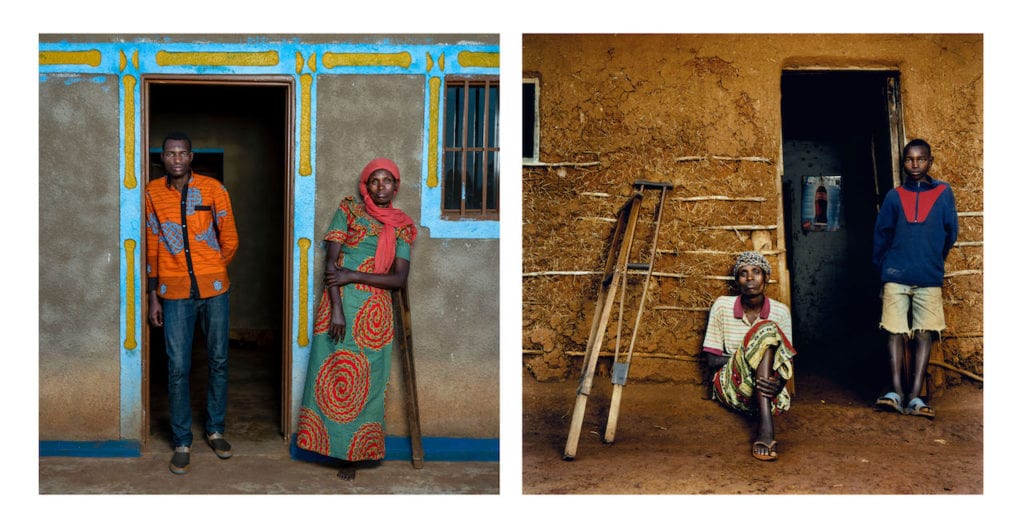

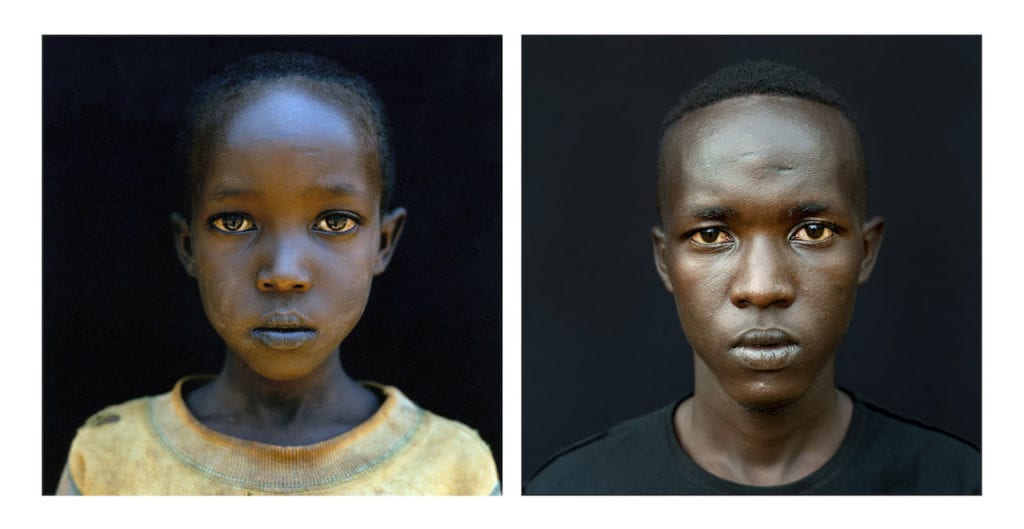

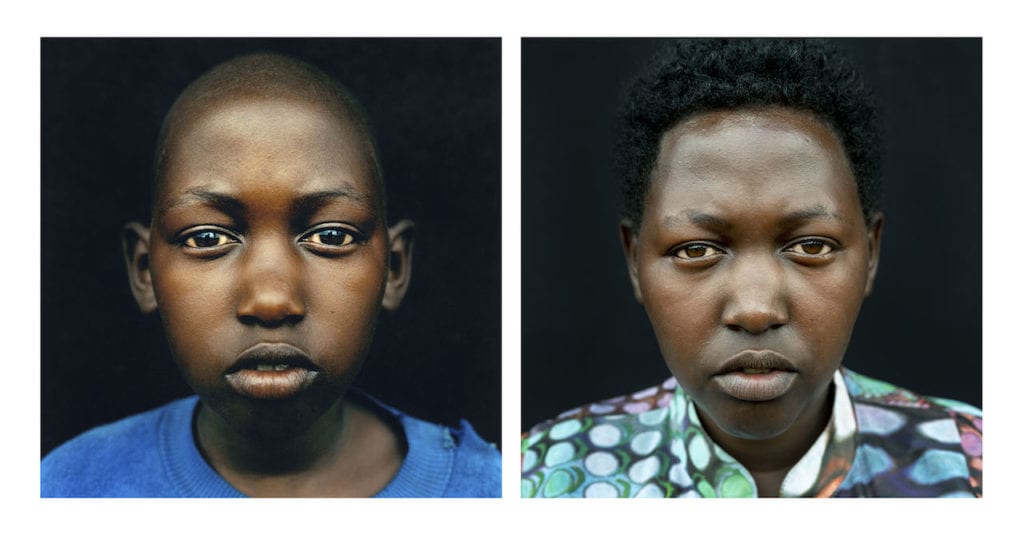

Imagine deciding to photograph the legacy of this utter horror. This is the task that documentary photographer and social activist Jonathan Torgovnik set himself in 2007. He spent two years tracking down and interviewing 40 women across Rwanda, each of whom had children of 10 years old or older. Alongside each interview, Torgovnik took the women’s portrait with their children, o en in or around their homes. He called the series Intended Consequences. “I knew going in that I was going to hear stories of unimaginable tragedy,” the Israeli- born photographer says from his home in Cape Town. “But I didn’t anticipate how deep and long-lasting the impact would be. It is in some ways similar to the Holocaust. It was such a severe trauma. It was so fast-moving and so extreme. And the women were left carrying it, without being able to share it, for so many years a afterwards. When I got there, I found people who really wanted the world to know.”

His sense of trauma, Torgovnik says, has been passed down. “If you compound all these elements – of experiencing violence at such a young age, of not having a family, of then being told you’re the child of the man responsible for killing your mother’s entire family,” he says. “It’s devastating.” The testimonies he gained are almost overwhelming in their starkness. A mother called Verena told Torgovnik: “I cannot really tell you how many men came to rape me. I can’t count them. All I know is that months later I discovered I was pregnant. I tried committing suicide twice. Now I live with HIV/Aids.”

Torgovnik identifies as a campaigning humanist photographer, one who believes in the power of photography to stimulate real-world progress. “The idea of creating social change through photography is still there and it still exists,” he says. “I know there’s a lot of scepticism about whether socially engaged photography really makes a difference, but I’m a firm believer that it does, and I believe we should attach a call of action to our stories. And people do care.” His words are backed up by numbers. After completing the initial round of images in 2007, he agreed to let the story run in The Telegraph’s Saturday magazine. At his insistence, the newspaper set up a fund for the women, and reader donations came to more than $130,000. With the money, Torgovnik founded the charity Foundation Rwanda, which helped to provide counselling and psychiatric care, amongst other things, to the survivors of the genocide. It has gone on to support 850 families across Rwanda, and has since raised more than $2.5 million.

“The Foundation is an integral part of the project,” he says. “But it wasn’t part of [my thinking when shooting] the original series. It came from the seed money that was raised from the initial portraits. Once these massive donations came in, it became clear to me that we had to set something up.” Torgovnik remained intimately involved

in the Foundation and in the run-up to this April, which marks the 25th anniversary of the genocide, he decided to return to Rwanda to revisit the families he met 12 years ago. With support from the Pulitzer Centre on Crisis Reporting, he reprised the portraits of mother and child – o en in the same geographical location of the original images. He was able to conduct secondary interviews with the mothers – but, crucially, with the children too. Here, the children of the genocide speak for the first time, as young adults, of their experiences.

“I felt the need as a photographer to go back,” Torgovnik says. “To not forget the needs of the subjects whom I worked with 12 years ago. I wanted to go back and collect more of their stories, to give them a platform to express themselves.” What did he notice, I ask, about the women he met in 2006 and 2018? “There was a huge difference,” he says. “In terms of their self-esteem – their confidence, the way they can walk in their communities. They walk with their heads up now. They are still struggling in many ways, but there’s been some healing.”

That slither of hope is reflected n the sentiments of the children. Robert, son of Valerie, told Torgovnik: “My mother disclosed to me that I was born as a result of genocidal rape a er my aunties, the sisters of my mother, would call me Hutu and used bad words towards me. My mother called me to the house and we sat down and she started telling me how I was born as a child of a killer, and that the man who raped her was a Hutu, and that she had no role in having me with this man but it was forced, and that this man was not good. He killed many people. But my mother loved me as who I am, as her child. She encouraged me not to be worried about what the sisters tell me, but to think about how much she cares about me. Many mothers avoid saying the truth because it is difficult. But the fact my mother had the courage to do it made me happy. It made me increase my love for her.”

Torgovnik’s portraits are moving to behold. To view them is to experience the survivors’ eyes locked into our own. Shooting such images evidently left a deep emotional impression on the photographer. He would take the portraits directly after the interviews, “so they had just trusted me enough to disclose to me the most intimate and painful things they went through,” he says. He speaks of the sensation of there being something akin to “an unspoken language” in the taking of the images: “You’re standing in front of them, you’re looking at each other in the eye, the camera is there and you start shooting, and a dialogue at some point starts to take place. You let it unfold, and a gesture or a look they share with you suddenly assumes this incredible power.”

ere are moral considerations to such a project. An o en-used criticism of charity work in Africa is that of being a ‘white saviour’, an accusation recently levelled at Comic Relief by the Labour MP David Lammy, a vocal advocate of minority rights. I ask Torgovnik if he had any thoughts on such accusations. “I definitely don’t see myself as a white saviour,” he says. “And I don’t think it’s an accusation, by the way. It’s very popular now to talk about the issue in that way – and I understand the issue. But I’m a documentary photographer, and I saw there was a void. No-one was really touching the issue of children born of rape because of the sensitivities. But a lot of people came together to do something about it. And that all came from using photography to explore an unreported story. And I’m proud of it.”

So how is Rwandan society coping today, I ask? “It’s a very tough question,” he says. “There is a strong government push to promote reconciliation. There’s an effort there to get people to move on, to not dwell, to go forward together. And if you went to Rwanda today, you would tell me, ‘I don’t feel anything related to the genocide.’ It’s like it doesn’t exist at all on the surface. And the country has gone a long way, and developed a lot. But there’s a strong undercurrent – a population of trauma. e people that went through it will be scarred for life. We can’t just pretend that doesn’t exist, or try and erase it.”

This article was originally published in issue #7883 of British Journal of Photography magazine. Visit the BJP Shop to purchase the magazine here.