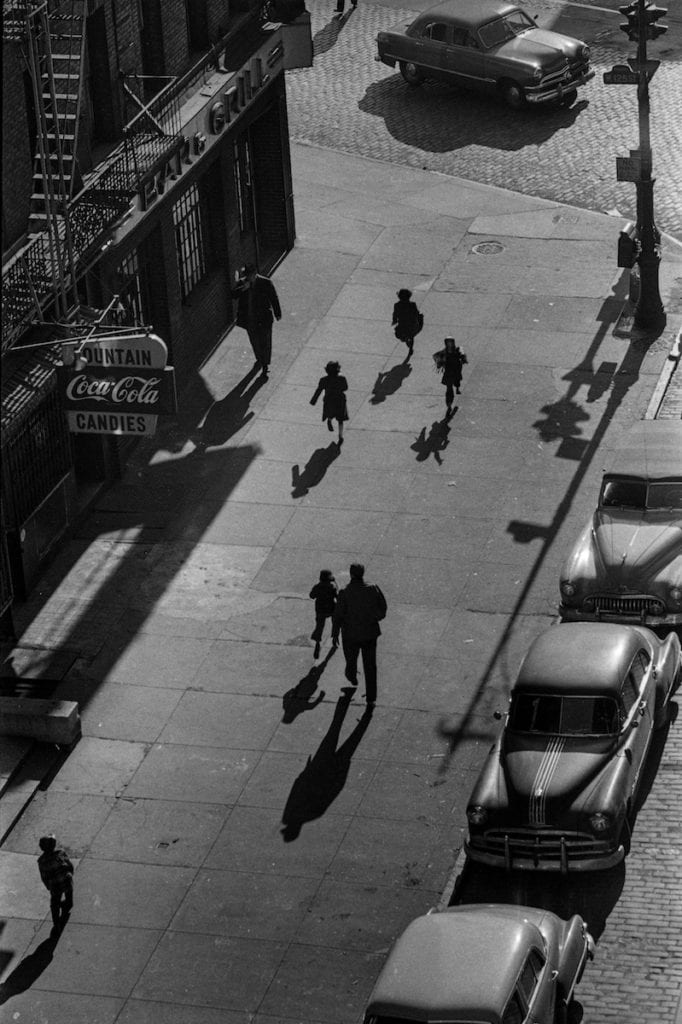

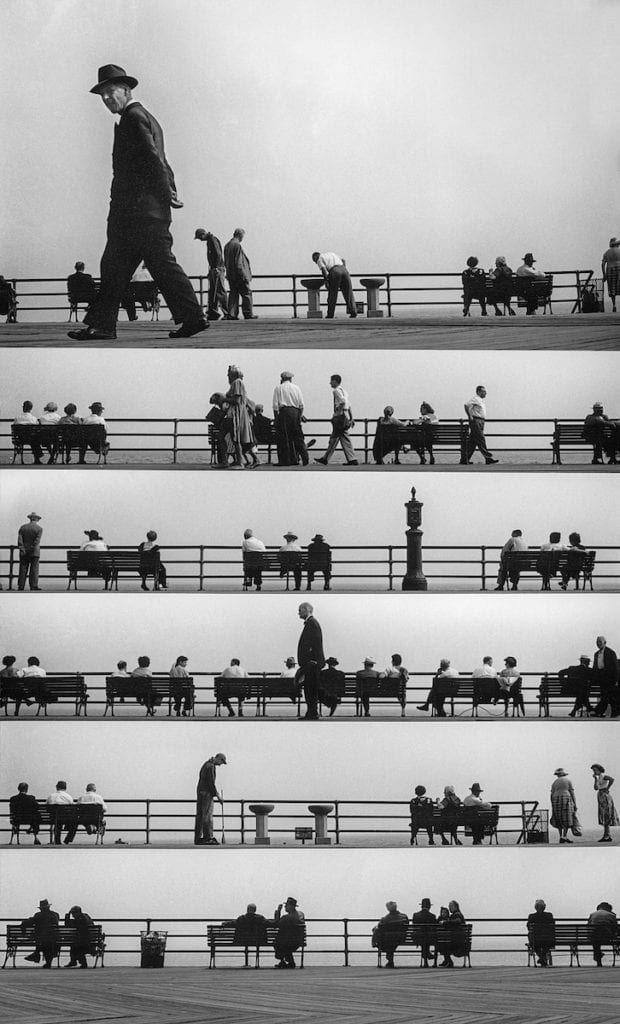

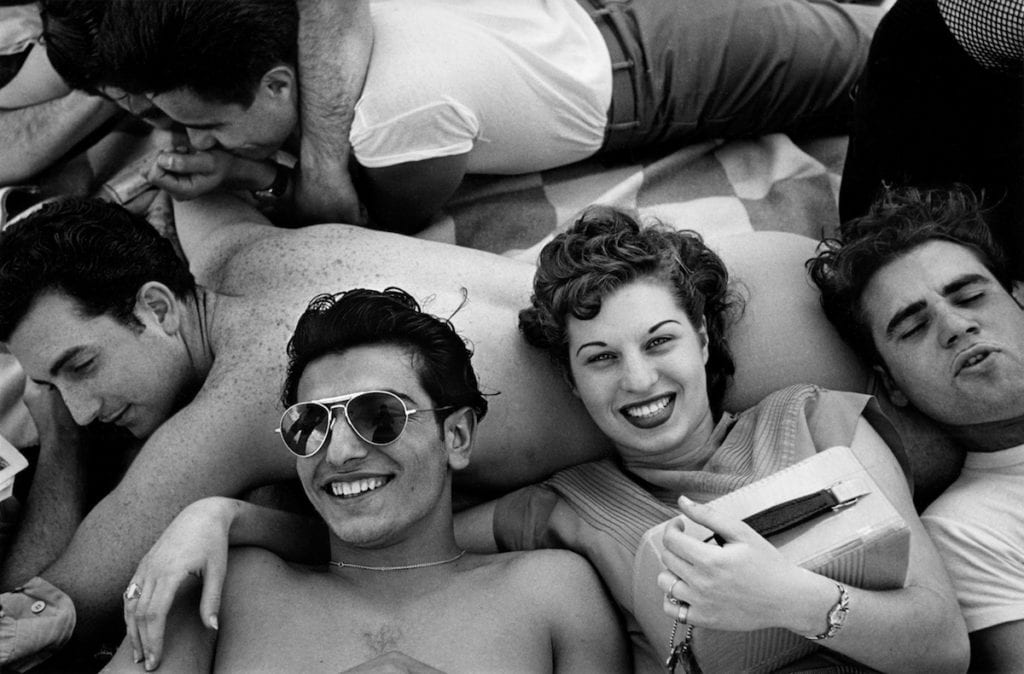

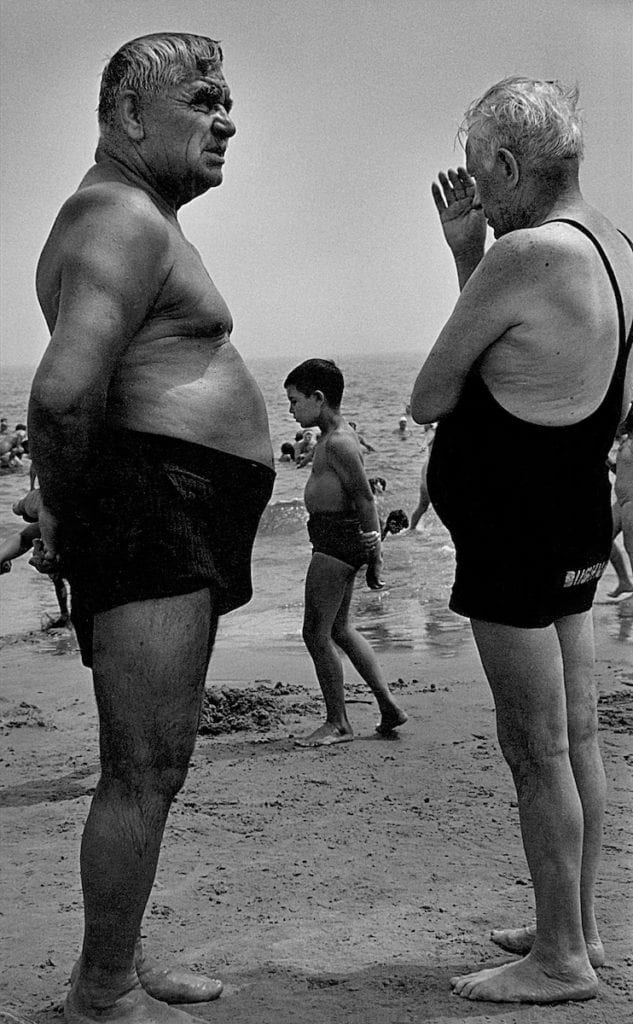

Harold Feinstein could have been a quintessential street photographer. His subject was 1940s New York; his medium, a Rolleiflex camera borrowed from a neighbour. The native New Yorker honed his skills on the beaches and boardwalks of Coney Island, wandering among the sun-drenched crowds in search of subjects. But, his work evades that categorisation. “The thing about Coney Island was not how to find a picture, but how to avoid it,” he reflects in Last Stop Coney Island: The Life and Photography of Harold Feinstein, a new documentary showing in tandem with the London exhibition Found: A Harold Feinstein Exhibition at 180 Strand, which delves into the story of the photographer who fell into relative obscurity, until now.

Feinstein, who died in 2015, framed familiar subjects in a manner that renders them remarkable – a skill that quickly gained him the recognition, and respect, of his contemporaries. He left home aged 15, escaping the wrath of his physically-abusive father for a room at the YMCA. The photographer was accepted into the Photo League aged just 17; the youngest of a group comprising some of the most noted American photographers of the mid-20th century, including Weegee, Robert Frank and Margaret Bourke-White. Two years later Edward Steichen purchased two of his prints for the Museum of Modern Art’s permanent collection. He was praised by peers, curators, and critics alike: in 1954 Feinstein had his first exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art; around this time, the formidable W. Eugene Smith entrusted the photographer with the layout for his Pittsburgh Project.

However, Feinstein’s renown was short-lived. This was, in part, down to his decision to withdraw from Steichen’s group photography exhibition The Family of Man – a monumental exploration of human experience, which toured the world for eight years and was seen by more than 9 million visitors – after he was asked to relinquish control over the size and crop of his images. As the spotlight shifted onto Feinstein’s more successful contemporaries, the photographer left New York for Philadelphia and threw himself into teaching. “Part of my journey in life has been running away from the establishment, just as running away from home was important,” he explains in Last Stop Coney Island.

Feinstein achieved some commercial success at the end of his life with One Hundred Flowers – an avant-garde photo book comprising scanned images of flowers. However, he remained relatively obscure. In 2011, director Andy Dunn contributed to a Kickstarter campaign to fund Feinstein’s first monograph. “His work was instantly appealing so it was an easy decision to support the book; then the thoughts of a film began to form in my mind,” he explains. Dunn took the plunge, producing Last Stop Coney Island. He also introduced Feinstein’s work to Carrie Scott – an American curator and writer – who curated the concurrent exhibition Found at 180 Strand.

In a conversation with BJP-online, Dunn and Scott, discuss the challenges and responsibilities involved in presenting Feinstein’s life and work.

–

BJP-online: What drew you to the story of Harold Feinstein and what motivated you to tell it?

Andy Dunn: When I think that a subject could make a good documentary I ask: “Is there a story worth telling? What is the value of a film beyond showcasing an artist’s work?” I would not have pursued the project if Harold hadn’t been such an inspirational character – it was the way he chose to live his life, being true to his art, which interested me most.

Carrie Scott: Andy and I were working together in New York and he asked me to take a look at Harold’s work. I had never heard of him and was cautious at first but then, like Andy, I started looking at his images and reading about his life – I quickly realised what an authentic artist he was.

Harold’s photographs are alive. They are genuine and spontaneous and make you feel exactly how you want to when you look at an image. I was drawn in by the romance of the imagery and the romance of Harold’s story, despite never having met him. I said to Andy: “You have got to do this.” He introduced to me Judith Thompson, Harold’s widow, and from there it was the most natural process.

BJP-online: So the project really evolved as you went deeper. Did distinct themes emerge as you continued to research and speak to people?

Carrie: Yes, because his story has not really been told before there was as sense of discovery, like peeling back the layers of an onion.

The first time I saw Harold’s images I thought: “How can I build on these? Clearly, he is massively under-recognised. What is going on?” Then, I learned he was a beautiful teacher who gave so much of his life to helping people discover their own authenticity and integrity.

So it was this organic process of getting to know Harold through his work (sadly, he had passed away by this point). I quickly realised how important Harold’s biography is to the history of photography and that we had to tell it. And we had to tell it in a significant way.

BJP-online: Did you feel a duty to present Harold in a certain way – what do you want viewers to take away from the documentary and the exhibition?

Andy: Yes, for me that is a big part of the job.

My approach to the film was partly led by what attracted me to Harold as a bohemian of sorts. But, it was also led by a sense of responsibility to create something that would not just be a hagiography. The film had to have balance and I wanted to reflect some of the costs involved in Harold’s unwavering commitment to his art.

I began the project when Harold was alive, but he passed away during the process. Because of this, I had to make decisions about how to handle certain themes in the knowledge that he was no longer here to speak for himself. I was really conscious that he had problems and pain in his life, and that this is relevant to his work. I had lots of conversations with Judith early on, to ensure that she would trust me to present him in a balanced way.

In the art-world, some people worry about the negative effect on an artist’s reputation and legacy that recounting the darker, or perhaps flawed, aspects of their character may have. “Don’t say they had an alcohol problem, better not to risk inferring that they were promiscuous” etc. But, I think the lifelong struggle between the darkness and the light is where a lot of great art comes from and it was certainly a key part of Harold’s psyche.

BJP-online: How do the different narratives in the film work with those in the exhibition? Are similar themes covered by both the film and the exhibition?

Carrie: One of the things that I was inspired by when watching the film was Andy’s ability to bring Harold to life. Andy and I began to talk about the ways that I could do that in the show and not only via the prints on the wall. So the show employs a range of media. Before you even see one of Harold’s images, you hear his voice – it is a recording that he did when he was taking some curators around an exhibition. There are also manuscripts from the lectures that he gave, and Andy has cut some small excerpts of the film that will be included. So, hopefully Harold’s presence is there, right from the beginning.

BJP-online: The sequencing of images in the film is so fluid. How did you decide what photographs to include in the footage and in the exhibition?

Andy: Having access to Harold’s archive was one of the joys of making the film. I love contact sheets and rummaging through boxes of proof-prints – there is always the thrill of not being quite sure what you are going to find.

You can learn about how a photographer worked by looking in their archive. Harold had phases where he shot a role of film and every image would be different. He had other phases when he would fill an entire role with the same scene.

I knew that there were 50 or 60 classic images, which should definitely be in there. Judith also knew about some images that Harold was particularly fond of – I wanted to include those too. And then there were the pieces that I personally just liked. Sometimes we would notice that there was a shot in the moving archival footage, which echoed one of Harold’s photographs and that would influence what we selected too.

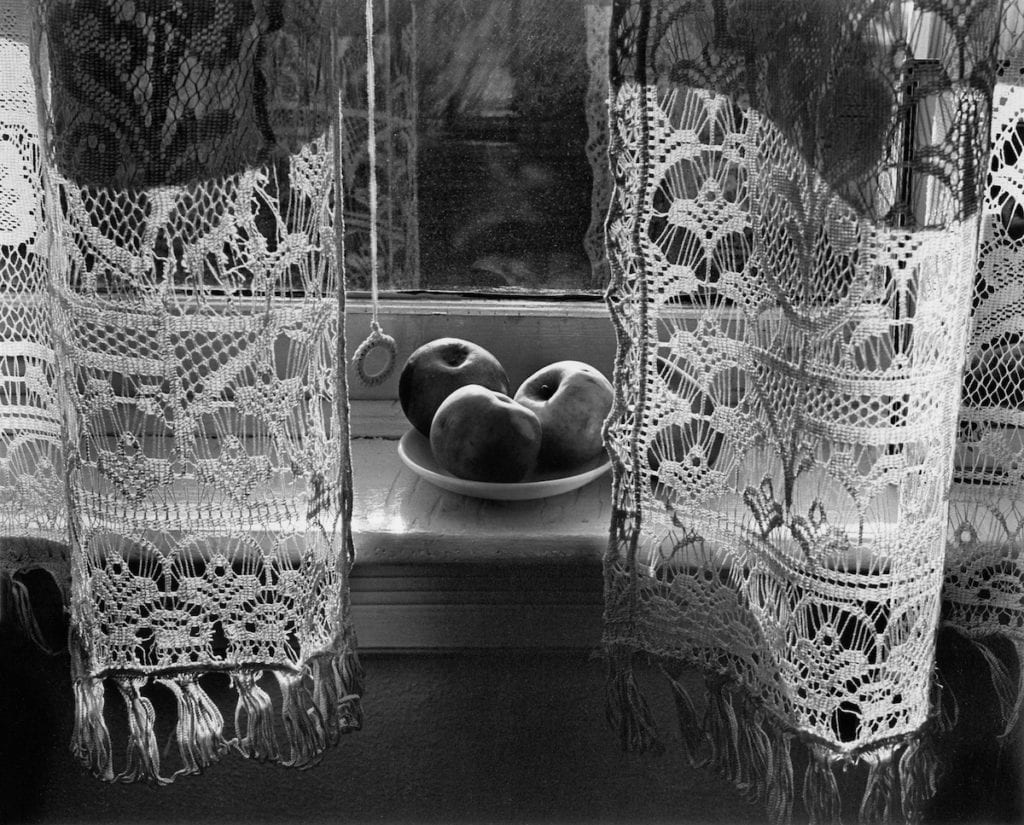

Carrie: When I started talking to Judith I was pleasantly surprised that the archive was actually very well-organised. There were three groupings that I knew I wanted to show – Harold’s work from Coney Island, his street-photography, and his still lives, nudes and landscapes. Images just worked with images – that is the nature of his archive.

There will also be additional prints that people can leaf through with white gloves. So, in total, you have about 70 images that people can look at.

Andy: The print is also key. Harold was an amazing printer and I think that the exhibition will convey that.

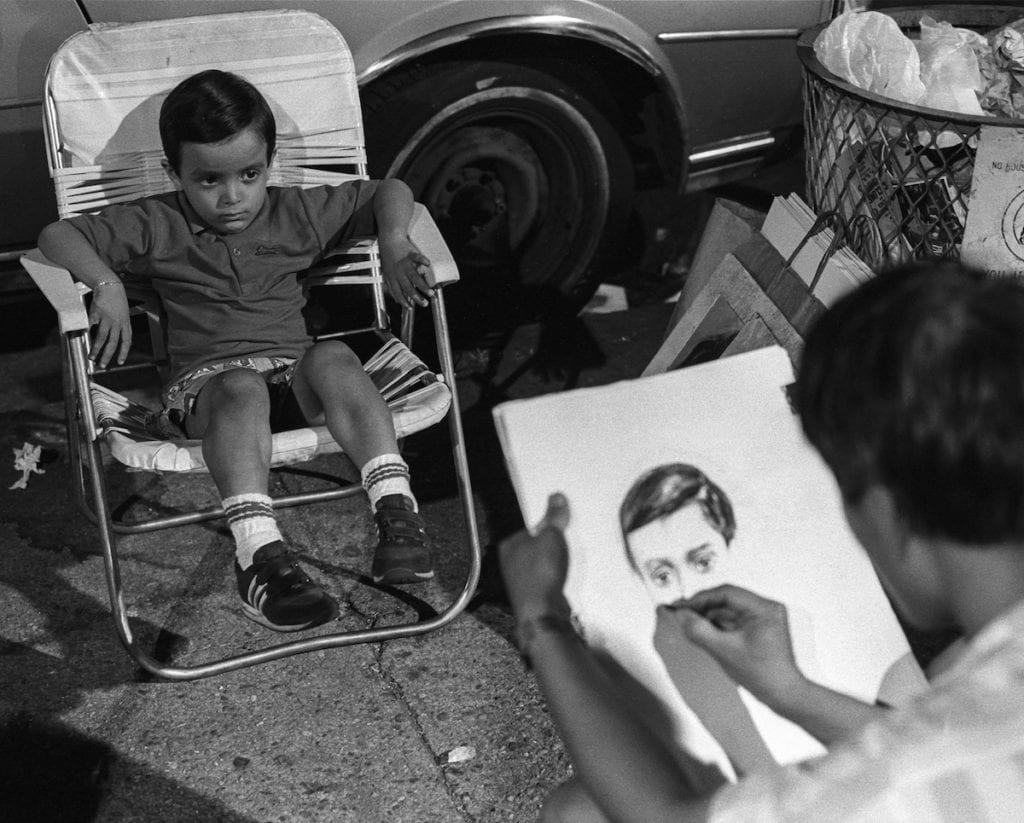

BJP-online: One thing that really stuck out was how close he got to his subjects, and the unconventional angles that he often employed. New York City has been the subject of so many photographer’s work. But, it was unique to see his subjects framed in this close-up way.

Andy: When you look at his photographs you know he isn’t self-conscious. He had an innate sense of composition and balance. His work doesn’t feel like someone trying to “make art”; it looks like someone reacting to what feels good instinctively.

Carrie: That element of proximity is so significant. With many other street photographers, you get this sense that they held back – there is some distance. But Harold is right there. That was particularly brave back then when the camera was not so commonplace and when you consider that his subjects are mostly not his friends. But, Harold manages to cut through all of that. And so do the people staring back through his lens. They are sparkling and they look like they love him. They are at ease with the process and they are just happy to be there. That was what hit me straight away.

Last Stop Coney Island: The Life and Photography of Harold Feinstein will premiere in the UK on 15 May 2019 at Bertha Doc House, with additional screenings on Sunday 19 May and Wednesday 22 May. Further London screenings will be announced soon here.

Found: A Harold Feinstein Exhibition, curated by Carrie Scott, opens on 14 May at 180 The Strand, London.