Harley Weir’s most recent publication is visually complex. But, the concept behind it is relatively straightforward. “I have always wanted to show something of my own desire – to celebrate the male form,” she says. “I want to make things I would like to see.” Growing up, Weir felt sexualised photographs of men were lacking. Aside from the archetypal, “poster guy” of the 90s, complete with the obligatory six-pack, images that appealed were few and far between. “I cannot speak for men, but I find the confines for a ‘man’ just as suffocating as those for a woman,” she says.

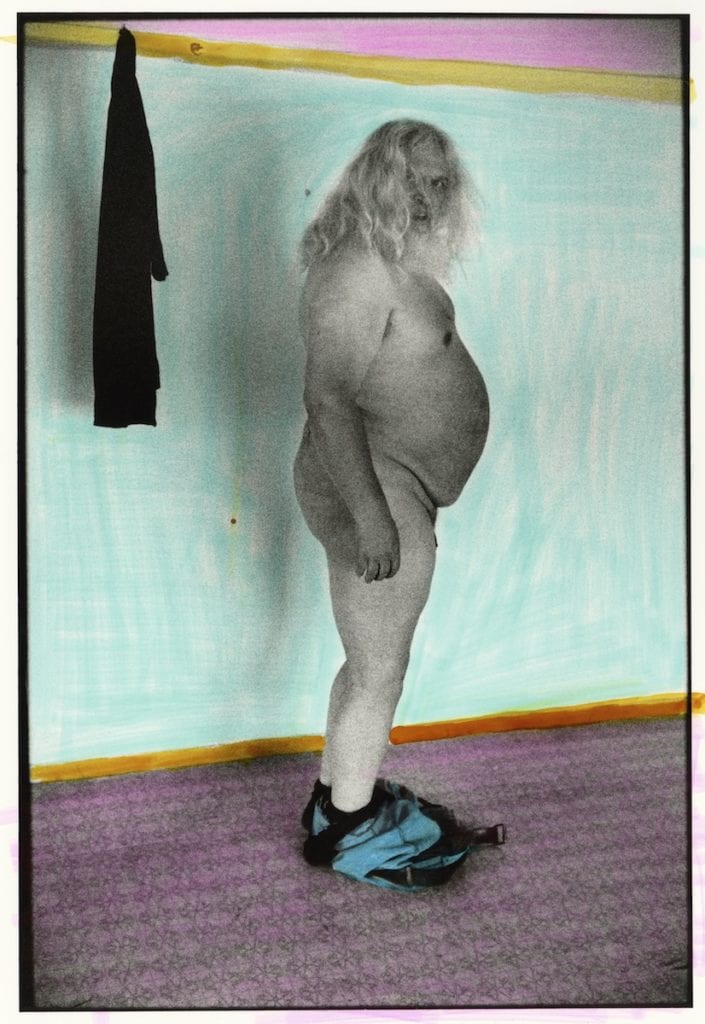

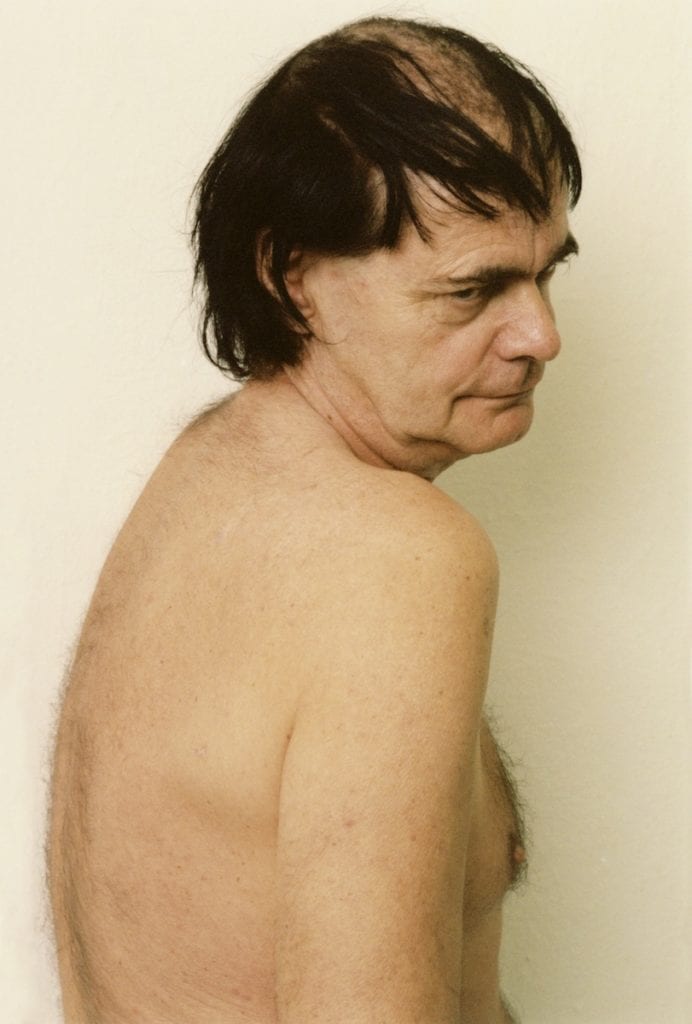

Father, as it is aptly titled, undoes such constraints. It is as much for Weir as it is for the ‘men’ spread across its pages. The photobook extends the photographer’s commitment to transgressing boundaries, visually opening up the definition of masculinity as it is traditionally-defined, and encourages us to think about what the term means in a broader sense. Gender becomes about the desire it provokes – whatever that may look like.

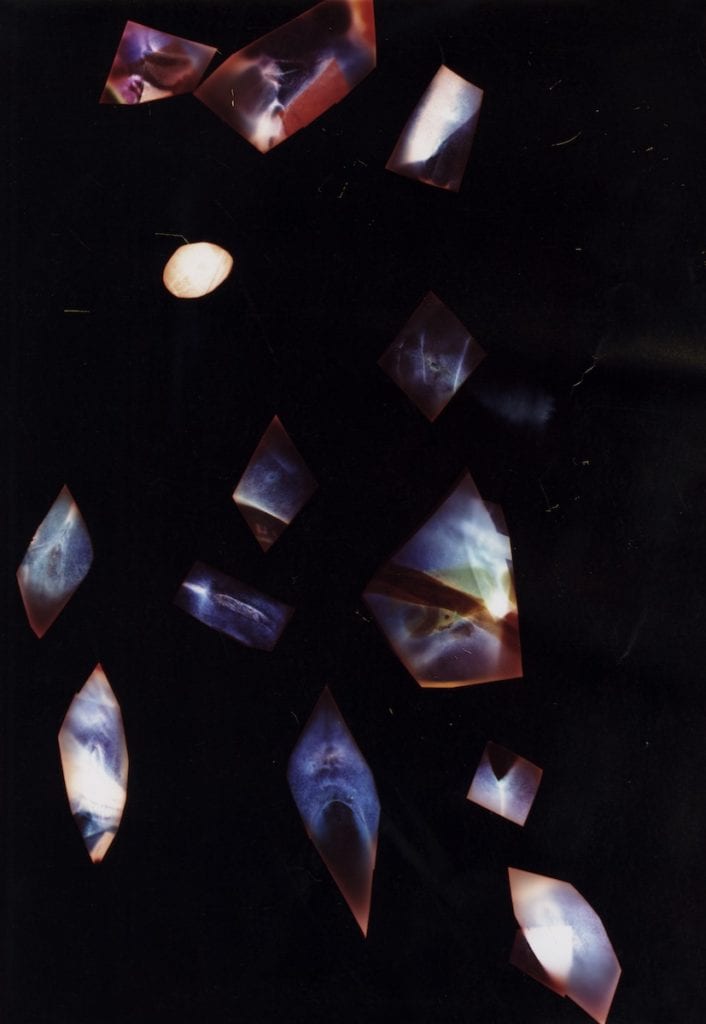

“It reminds me of a quote from John Berger in Ways of Seeing: ‘Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at’,” says Weir. “… I always thought, I watch men too, not in a creepy way but I desire others. There is this view that women are acquired and that they don’t have their own sexuality.” The multiplicity of images that comprise Father express that desire. Some photographs are overtly sexual. Others are more covert: the delicate application of pink eye shadow, rumbled burgundy sheets, the head of a peculiar-looking plant. “I made photograms of objects and people, fluid paintings from spitting, peeing, cumming, bleeding, dripping etc on photographic paper,” says Weir. “I used to make things growing up, I have really missed the physicality of working with my hands. Printing in the darkroom satisfied that need for so long but it was great to have time again to experiment and fall back in love with the process.”

Weir’s work sits at the intersection of fantasy and documentary. Her visceral images transform their often mundane subject matter into works of art. Both a photographer and director, Weir originally set out to be an artist, completing a BFA at Central St Martins in 2010. Outside of her fashion work, the photographer’s personal work includes images made during trips to conflict zones, including Israel’s West Bank and the Jungle in Calais.

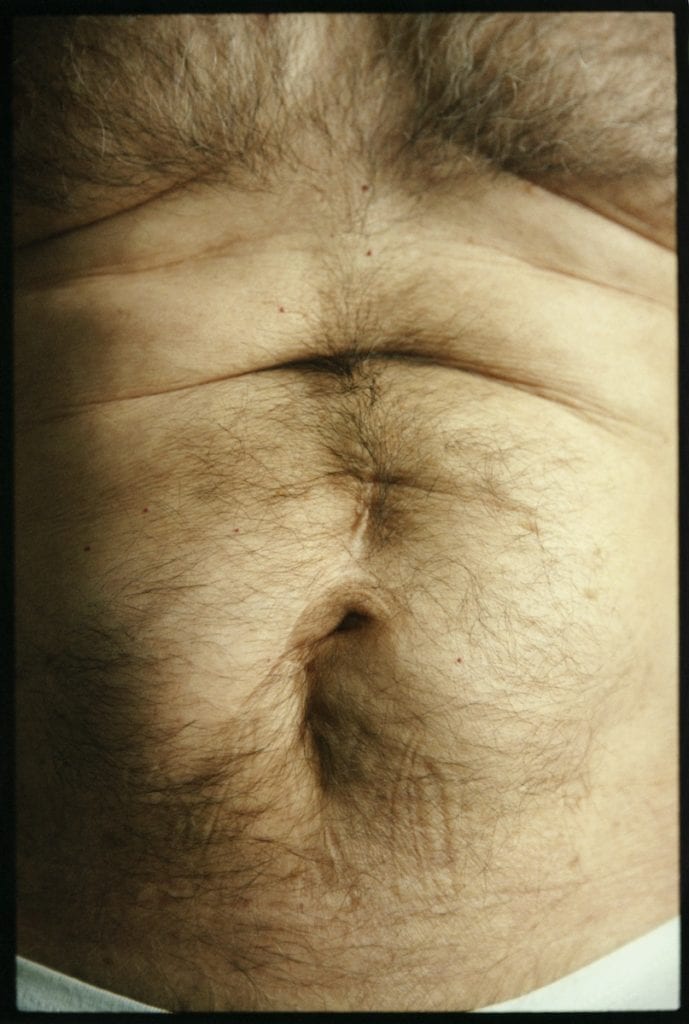

Father began as a collaborative project with Weir’s real dad. “In the end it is nothing directly to do with him,” she says, “I kept the name as it seemed to make sense when I was thinking about the archetypal man, the father being the first most of us meet in our lives.” Many of the images are over 10 years old. And yet, despite this, the photographer’s distinct style draws the work together. From the dimly-lit torso of a young man framed front-on, to a hairy nipple bathed in pink, fluorescent light.

Father also carries a wider significance along with being a deeply-personal exploration of desire. “I wanted to show men’s bodies in a beautiful yet varied way,” says Weir, “a true appreciation for all the irregularities I find so captivating. I know how it feels to have a body that just does not replicate what we see on billboards and I do not think that men have any more freedom here.” Outside of the physical, the photographer also points to the importance of collapsing the divide between masculine and feminine. “I feel like there is this pressure to be hyper-feminine or hyper-masculine,” she continues, “staying within such tight constraints really does not make me happy. The men I love most in my life are comfortable with their female traits and vice versa in the women I adore.”

Father encapsulates this. From the made-up hosts of Japanese nightclubs to transgender sex workers in Mexico, the subjects depicted defy masculinity in the conventional sense of the term. “I believe for things to move forward we need to heal things on both sides, “ says Weir. “Women need to be more in touch with their masculine sides and men need to be more in touch with their feminine sides. I hope these images can start a trend that continues to open up the discussion on gender and sexuality.”

harleyweir.com