Lola Flash’s portraits are free to speak for themselves. Captured on a large-format camera, her subjects hold our gaze. They stand tall against hazy, urban skylines, cast in the golden glow of the early evening sun. “I want my subjects to be seen, not scrutinised,” says Flash. “In the dictionary, the word black can be defined as gloomy, dirt-ridden, and evil. Let’s change those definitions. Black is beautiful, even though that is kind of a cliche, it is true.”

Flash’s series [sur]passing, which sat at the centre of her first major solo exhibition in London, endeavours to do just that. The monumental portraits create a space in which her subjects can stand free from scrutiny and judgment. The stills are decidedly individual, yet there is a certain strength that runs through them. “Right before I shoot, I say to people I want you to think about pride and power, and think about someone you admire or look up to,” says Flash. “For lack of a better word, when I take a picture it is like magic.”

![lola-flash-[sur]passing-03](https://www.1854.photography/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/lola-flash-surpassing-03-810x1024.jpg)

The series also has an important underlying narrative. The individuals depicted span a spectrum of skin tones highlighting the impact that skin pigmentation plays on black identity and consciousness. Kobena Mercer, the British art historian and writer, coined the term ‘pigmentocracy’ to describe this reality; a form of discrimination that dates back to Plantation societies in which the division of labour was dictated by a racial hierarchy.

Flash’s series developed out of her own experiences. Moving to London from New York in the 1990s for Graduate school, the photographer was taken aback when people referred to her as mixed-race — a term she had not been identified by before. The experience made Flash reflect on her appearance; the photographer realised that she had never struggled to get a job and that this could be directly related to the lighter tone of her skin. “I thought about a story that my Grandmother told,” continues Flash. “When she got the train to the south from the north, she was always able to pass because she is light-skinned and has red hair, and then I thought maybe I have had experiences akin to that without even realising it.”

Nonetheless, until recently, Flash remained relatively unknown in a professional capacity – her race and sexual orientation unwelcome in the spotlight. “I am finally getting a little bit of space,” she says. “ … I have waited 40 years to be seen … But, it is still that token mentality. In some ways, I am just like ‘if I have to be a token I will be one because there needs to be a place to start’.” Despite her success, Flash remains committed to carving out a place for the queer, black community. She aspires to the example of Harriet Tubman, an American abolitionist and political activist, who escaped enslavement and proceeded to orchestrate 13 missions on which she rescued many others. “Tubman risked her life numerous times to go back and forth to help people escape,” says Flash, who is steadfast in her dedication to platforming, and preserving the legacy of, LGBTQIA+ and communities of colour worldwide.

![lola-flash-[sur]passing-01](https://www.1854.photography/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/lola-flash-surpassing-01-815x1024.jpg)

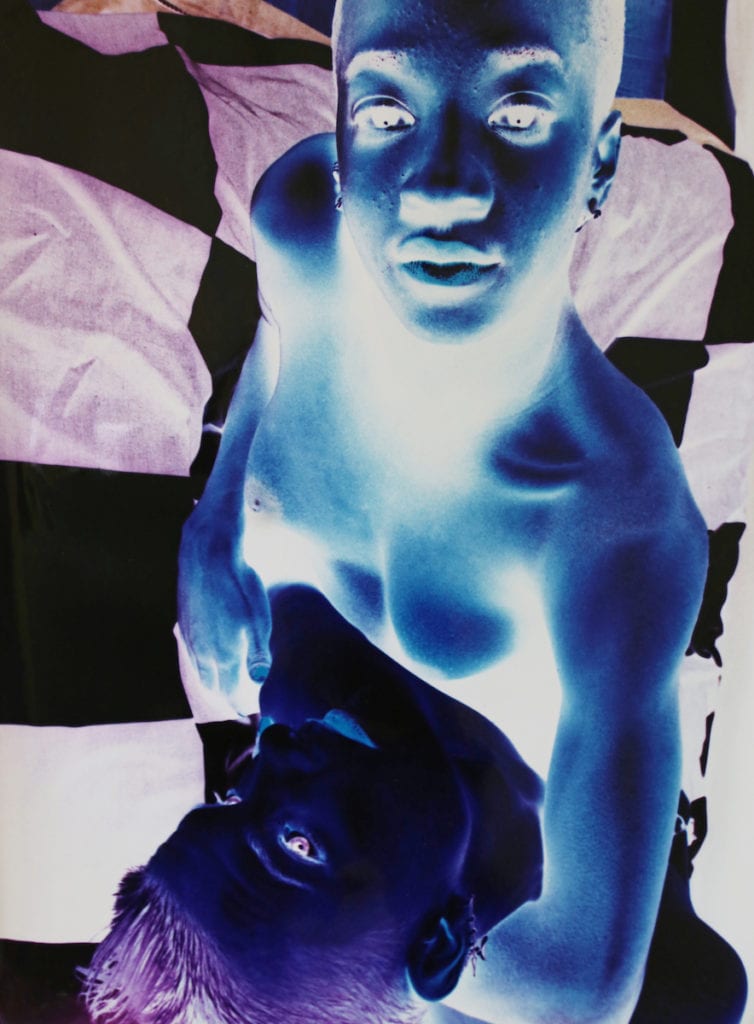

Activism has been central to Flash’s practice since its inception. The start of her career coincided with the advent of the HIV and AIDS epidemic in mid-1980s New York. The photographer became deeply involved with the activist group ACT UP – documenting and participating in the organisation’s activities. It was around this time that Flash also developed her signature cross-colour style. “It was a mistake,” she remembers. The process inverts hues, removing true-to-life colours and their inherited associations: “Blue skies become orange, white clouds become black … a black person becomes white; a white person becomes black”. The process lent itself perfectly to the subjects Flash was photographing. Cross-colour visually eliminated the black/white binary and created a veil of anonymity for those featured. “Lots of people were really in the closet,” says Flash. “But, no one could recognise you if you were orange or red. It really obscures the presence of the person.”

A number of works from Cross Colour featured in the show, alongside photographs from Gay to Z and Flash’s ongoing series LEGENDS, which comprises portraits of prominent members of queer and non-gender conforming communities. “I feel like I should be proud of what I have done,” says Flash. “But, when there are so many other battles that still need to be won, sometimes it is hard to just sit back and puff up my chest.”

The photographer is far from finished. “I really want to rewrite the history that has been thrown at us,” she continues. “I mean it is really pretty simple. I just want people to see the beauty in us.”

Lola Flash [sur]passing was on show at Autograph in London until 17 August 2019.